Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Storytelling in Games and Interactive Media. Chapter 3: Freedom of Choice

In the last part we talked about a story's setting and structure, drawing similarities to other media such as screenwriting. However, film is not an interactive medium, and as such not subject to the topic of this third part: player agency.

"Everything that is really great and inspiring is created by

the individual who can labor in freedom"

- Albert Einstein

Introduction

In the last part, we talked about a story's setting and structure, drawing similarities to other media such as screenwriting. However, film is not an interactive medium, and as such not subject to the topic of this third part: player agency.

Agency, as described by Tynan Sylvester(2013) is "the ability to make decisions and take meaningful actions that affect the game world".

According to Kent Hudson(2011), agency is essential to happiness if we follow self-determination theory(Deci, 1985). The element of autonomy in SDT describes decision-making as one of three key abilities allowing for optimal function and growth, as described in my 2020 article on psychological foundations of player motivation.

Pay close attention to Sylvester's formulation: meaningful actions, that affect the game world.

Too many "plain" choices can be negative. The notion of absolute freedom of choice is contradicted by psychologist Barry Schwartz in his book and 2007 TED talk "the paradox of choice". According to Schwartz, the overflow in choices ultimately ends up reducing happiness. The speaker discusses two negative effects resulting from this overflow.

First, it produces what he calls "paralysis rather than liberation", as it becomes increasingly difficult to choose at all.

Second, even if we end up making a choice, we will be less satisfied than we would have been with fewer options, due to the principle of opportunity cost. This economic principle describes that it is easier to imagine that some of the many other choices would have been better; how we value something depends on what we compare it to.

Third, opportunity cost leads to escalation of expectations. With more options available, expectations go up. As Schwartz puts it, "you will never be pleasantly surprised because your expectations have gone through the roof". Schwartz concludes "there is no question that some choice is better than none, but it doesn't follow from this that more choice is better than some".

Parity

Many agency problems, according to Sylvester(2013), appear when the player's motivations don't align with the avatar's. The author coins the term "desk jumping", referring to Deus Ex's character controller's ability to jump around on office desks, while the protagonist avatar, a spy, is supposed to move silently. Harrison Pink(2017) refers to this difference between player and avatar motivations through a less analogical term, describing "motivational parity" in opposition to "emotional parity".

We will refer to imparity as the misalignment between player and avatar, and to desk-jumping as any action into which motivational parity might translate.

According to Sylvester(2013), we can disallow desk-jumping entirely, however, this weakens engagement by destroying suspension of disbelief in the game mechanics. Disallowance is therefore a valid fix for the symptom that however doesn't address the underlying issue. This practice is in itself a risky one, as Pink(2017) warns. He recommends instead to "sacrifice playtime to sync the avatar's emotional state with the player's motivation", and advises to be "aware that whenever the game asks the player to make a judgement call or places an obstacle, this will make them re-evaluate their emotional attachment to the avatar".

Disallowing desk-jumping can however work well when fictionally justified. Sylvester(2013) gives the example of critically acclaimed Portal. Portal doesn't solve any of the mentioned problems, instead, it elegantly moves around them.

We can also simply ignore desk-jumping, as is the case in Half-Life 2. When shooting the companion character, nothing happens. She isn't invincible, the bullets just don't hit her. There is no blood, no animation. Ignoring the practice, where possible, is often better than disallowing or punishing it, as the player feels less controlled, and thanks to the lack of result, soon loses interest in it. (Sylvester, 2013)

Figure 1 shows how bullets will always fail to hit Alyx, without interrupting the narrative immersion thanks to recoil.

Figure 1: Burak Emre. (2019). Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8NopUHfPu4

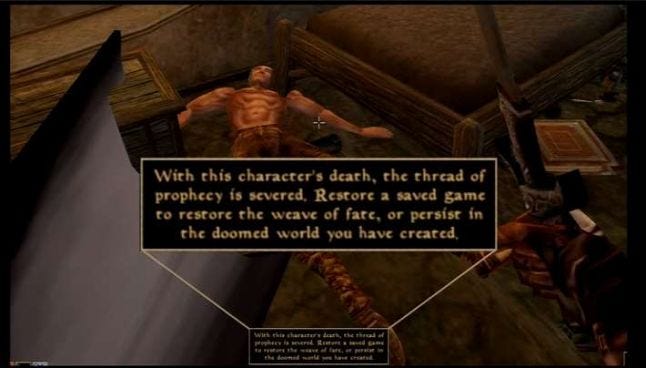

In The Elder Scrolls: Morrowind, it is possible to kill the main questgiver. The game does not avoid it in any way, granting full agency to the player. Instead, the game simply responds with a message embedded into the narrative while indicating that the game can't be completed within that line of happenings. (Hudson, 2011)

Figure 2: Hudson, K, (2011). Player-Driven Stories: How Do We Get There?[19]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qie4My7zOgI

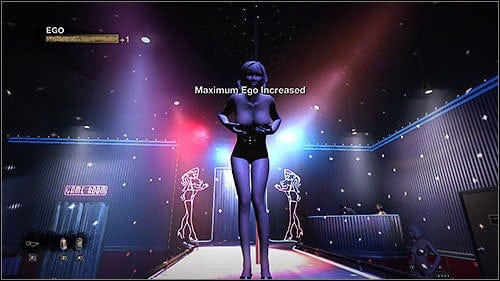

On other occasions, we can incorporate desk-jumping into the narrative. For example, in Deus Ex, the player can go into the women's restroom. When doing so, he is confronted by a shocked female coworker and later told off by his boss. It’s a funny response to a funny action by the player. Sometimes, such as Duke Nukem Forever, those type of actions is directly incorporated into the mechanics. The health bar is replaced by "ego", which expands whenever Duke plays pinball, lifts weights, throws basketballs around, and harasses strippers. This reinforces Duke’s over-the-top macho characterization. (Sylvester, 2013)

Figure 3: Game Guides. (2016). Duke Nukem Forever Guide. https://guides.gamepressure.com/dukenukemforever/guide.asp?ID=11594

The best solution, according to Sylvester, is to design the game for parity. In Call of Duty, it is possible to refuse to complete objective, fire, or block allies, but it rarely happens as the fast-paced combat is so compelling.

We will refer to this option later, in the fifth installment of the series which deals with character design.

When tanks are exploding, commanders are urging troops forward,

and enemies are swarming like flies, the player gets so keyed up

that the impulse to fight overrides the impulse to act like an idiot

-Tynan Sylvester (2013)

Parity isn't limited to player-controlled action. Thomas Grip(2016) coins the term agreeable action-outcome as the alignment of automatic pawn actions to player intentions. He gives two opposite examples in Assassins Creed; when the character automatically jumps over a roof while the player is running, this is agreeable, since it fits the normal instinctive behavior the user would have when being that character. On the opposite side, gripping on walls towards an unintended side is non-agreeable action-outcome.

It is important to note that the player's motivation doesn't need to come from the same source as the avatars, only the same goal. The avatar in Call of Duty is a soldier motivated by honor, loyalty, and fear, while the player is motivated by energy and entertainment. (Sylvester, 2013)

Those are different motivations, that translate into an agreeable action outcome.

Given the possibility of an avatar's automatic actions, Kent Hudson(2011) draws further importance to equality between player and character. In his talk, he says that often the character is represented overpowered while the player just has to "make it alive to the next cutscene", and coining the desired opposite under the term of unified agency, which will herein be described as parity of power in order to follow the model of Pink(2017).

Reactivity

Matt Brown(2018) refers to improv comedy's "yes and" principle, drawing a synonymous to an infinite feedback loop mechanic between player and game. Remo(2019) translates this principle from improv into its medium-specific term, coining "reactivity". Reactivity, as Remo describes it, is a softer version of interactivity in that the game constantly listens and reacts to every decision the player makes, explicit or implicit.

Think of it this way. According to Mary Elisabeth(2017), "saying "no" [in a start-up company's meeting] decreases trust and makes you and your partner look less competent. You're building a company together, so build your story together". This translates to Remo's reactivity principle through emergent narrative. We don't want players to feel incompetent, instead, we want their worldview to be acknowledged in order to tell our story through their lenses.

In Forget Protagonists: Writing NPCs with Agency for 80 Days and Beyond, writer Meg Jayanth explains that player agency doesn't necessarily have to translate into action – in the traditional sense.

According to her, even if a player can't affect something directly, the possibility of having an opinion, reaction, or emotional response can be as powerful as allowing them to take action. Giving players this type of agency allows NPCs to have more development and depth in turn, to pursue their goal without being overridden by the protagonist.

The design approach to 80 Days assigns agency not as a neutral decision. According to Jayanth, "it might feel unfair to the player, but maybe unfair isn't the worst thing a game can be."

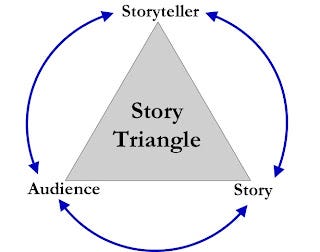

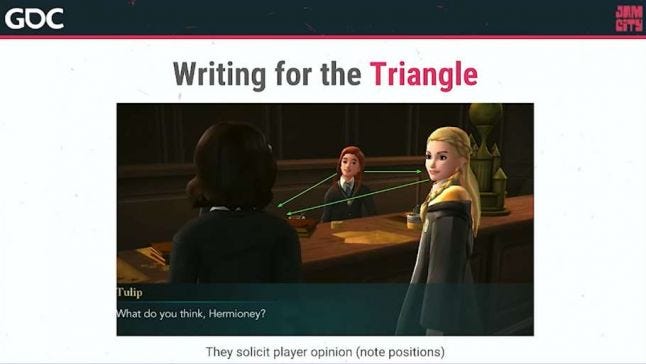

Ryan Kaufman(2019) talks about the narrative triangle as a form to represent the relationship between two NPC and a player character in dialogue. A concept abstracted from the story triangle that illustrates the relationship between story, narrator, and audience, and is in itself derived from Aristotle's rhetorical triangle, which encompasses reason, character, and emotion(Packer, 2014)

Figure 4: Packer, L. Ask the storyteller: The story triangle. (2014). True Stories Honest Lies. http://truestorieshonestlies.blogspot.com/2014/11/ask-storyteller-story-triangle.html

Kaufman uses this triangle principle to explain that even in normally bipartisan dialogue between NPC characters, it is always best to grant the player a degree of interactivity. This can translate to something as simple as asking the protagonist for an opinion(Kaufman, 2019), and paves the way for entire branches of narrative without even needing to branch the dialogue in itself.

Figure 5: Kaufman, R, (2019,03,18-22). Narrative Nuances on Free-To-Play Mobile Games[25]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILFzKNLAwVQ

"Freedom is not worth having if it does not include the freedom to make mistakes."

- Mahatma Gandhi

Freedom of Choice

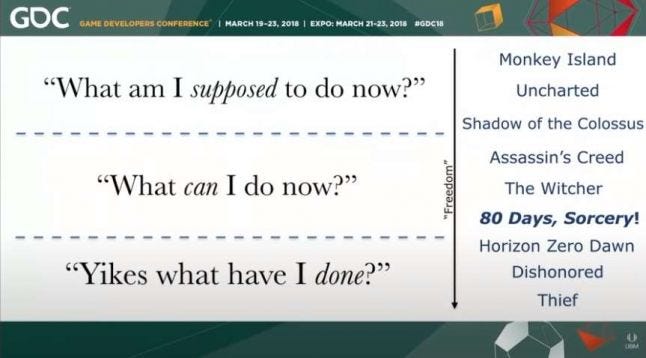

John Ingold(2018) differentiates agency from freedom, defining agency as " the player's ability to formulate strategies, execute plans, i.e. Act according to his own logic." To access freedom, on the other hand, we rather would ask "what question is the player asking themselves?"

figure 6: Ingold, J, (2018,03,19-23). Heaven's Vault: Creating a Dynamic Detective Story[10]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o02uJ-ktCuk

According to Ingold, it is perfectly fine to change the player's options all the time, as long as the options make sense. In systems-based games, the player can have the confidence of having the same options all the time, giving the ability to plan beforehand. However, according to the speaker, this problem goes away when the player can trust the author to provide the options that he wants at any moment.

Good choices will feel like they organically arise from inside the player's own mind. Strive to find room for personal expression in the choices. (Kaufman, 2019)

With people coming from all sorts of backgrounds, this eventually translates into a need for non-binary options, i.e. There should never be one ideal answer. As Josh Sawyer(2012) puts it, we want to avoid extreme choices. There should be a visible notion of good and bad, but at the same time, the available choices should lie somewhere within that spectrum and not at the extremes. Sawyer refers to the Greek tragedy Choice Agony to give an example of how both ends should have a tradeoff.

Following Failbetter Games CEO Alexis Kennedy (2016), while it is impossible to accurately estimate the choices a player might want to take, we can reduce them to their emotional nature. Paradoxically, those emotions are already manifested in the players head, however, instead of giving a choice between already manifested emotional states, we can provide actions to express that emotional state. (Kennedy, 2016)

Kennedy(2016) describes three further conditions to be met for "choices", a term used interchangeably with "options", to be compelling. Choices first should comment on, elaborate on, and align with the theme. Second, should be possible for the player to explain in one sentence (quality over quantity). Third, should have mechanical significance.

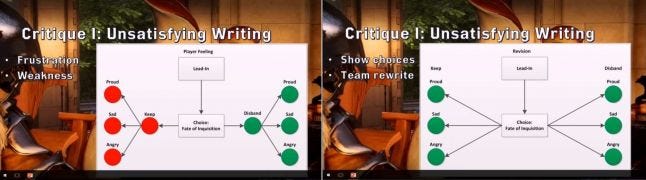

Talking about the Finale in Trespasser, Weekes(2016) mentions that giving up power needs to still feel like a win, giving the player a sense of pride and ownership. With the first iteration(left), playtesters felt unsatisfied with the binary choice, but the branching afterwards felt emotionally satisfying. Attachment in the final version had been increased by providing all choices at once.

Figure 7: Weekes, P., Epler, J. (2016). Dragon Age Inquisition: Trespasser – Building to an Emotional Theme[16,17]. Game Developers Conference.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ao4b4aN7RgE

Choice through Gameplay

We talked a lot about dialogue choices, however, the highest share of choices a player can make in most games is through action.

Those actions follow the game's mechanics, which usually are about moving, collecting, jumping, or battling. We can use these interactions to express human interaction. For example in Grand Theft Auto IV, the protagonist is presented with an old enemy and given the opportunity to kill him. The player can choose to shoot the man or walk away. Both actions are expressed through gameplay mechanics but are used here to drive a predefined plot. (Sylvester, 2013)

Another example is presented by Kent Hudson(2011) in Deus Ex: The player has the option to either fight or fly, resulting in the protagonist's brother's death or survival.

As designers, we are limited by the medium in every way that we in turn empower the player. (Sylvester, 2013)

According to Sylvester(2013), "the cleanest solution to the human interaction problem is to not do human interaction". Sylvester gives the example of Bioshock, where sane characters only speak to the player over radio or through unbreakable glass, and all characters that can be confronted face to face are violently insane.

Richard Rouse III differentiates, amongst others, between character simulation and drama management as opposing and mutually balancing storytelling techniques.

Character simulation refers to the result of AI randomness together with player agency – it deviates from the authored story towards a free one. Drama management, on the other hand, steers the experience back towards the authored path. Rouse draws the comparison to a DnD dungeon master, who allows for a lot of agency for the player, but constantly steers things back to the story intended to tell. (Rouse, 2016)

In conclusion, when designing a choice system, regardless of its used channel, we can use a set of conditions to control for satisfactory choices:

Relevance: Choices comment on, elaborate on, and align with the theme.

Clarity: Choices are easily understandable for the player. There is no unnecessary cognitive load.

Reactivity: The game world can respond in a meaningful way. There is a mechanical outcome from the choices. There can be a "yes, and".

Ambiguity: There is no clear answer, and every benefit comes with a downside.

Expressiveness: Choices allow the player to tell their own story, and project their desired personality onto their avatar.

Parity: At least one of the options allows for the avatar to act as the player would in that situation.

Actionable: Choices are not pure emotional expressions but actions into which those emotions translate.

NPC agency: The choice does not undermine the vividness of secondary or tertiary characters.

Previous parts:

Part 1: Prologue

Part 2: Setting and Tools

Next parts:

Part 4: Structure and Devices

Part 5: Character Design

Part 6: Time and Space

Part 7: From Theory to Practice

References:

Sylvester, T. (2013). Designing Games. O'Reilly. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-games/9781449338015/ch04.html

Hudson, K. (2011). Player-Driven Stories: How Do We Get There?. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qie4My7zOgI

Renke, R. (2020). On Player Taxonomies and Motivations – Part 1: Psychological Foundations. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/on-player-taxonomies-and-motivations---part-1-psychological-foundations

Schwartz, B. (2007). The paradox of choice. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VO6XEQIsCoM

Pink, H. (2017). Snap to Character: Building Strong Player Attachment Through Narrative. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyQfP1GjdJ8&t=1657s

Burak Emre. (2019). Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8NopUHfPu4

Game Guides. (2016). Duke Nukem Forever Guide. https://guides.gamepressure.com/dukenukemforever/guide.asp?ID=11594

Grip, T. (2016). SOMA: Crafting Existential Dread. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhGgLagz3XI

Brown, M. (2018). Emergent Storytelling Techniques in The Sims. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YjuOSgPdtS0&t=3002s

Remo, C. (2019). Interactive Story Without Challenge Mechanics: The Design of Firewatch. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVFyRV43Ei8

Elisabeth, M. (2017). Saying "Yes, and" – A principle for improv, business & life. IMPROVE. https://medium.com/improv4/saying-yes-and-a-principle-for-improv-business-life-fd050bccf7e3

Jayanth, M. (2016). Forget Protagonists: Writing NPCs with Agency for 80 Days and Beyond. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLtATD6CF0E

Ingold, J. (2018). Heaven's Vault: Creating a Dynamic Detective Story. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o02uJ-ktCuk

Kennedy, A. (2016). Choice, Consequence, and Complicity. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-FfITxaXeqM

Kaufman, R. (2019). Narrative Nuances in Free-To-Play Mobile Games. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILFzKNLAwVQ

Packer, L. Ask the storyteller: The story triangle. (2014). True Stories Honest Lies. http://truestorieshonestlies.blogspot.com/2014/11/ask-storyteller-story-triangle.html

Rouse, R. (2016). Dynamic Stories for Dynamic Games: Six Ways to Give Each Player a Unique Narrative. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SsSh62mSPZE

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author

You May Also Like