Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Meaningful Choice in Games: Practical Guide & Case Studies

Meaningful choices pull at players' heart strings, making them look inside themselves. These choices are remembered as deeply emotional experiences, the moments that turn a game into art. But how do you create them?

I’ll never forget Boyd. May he rest in peace.

Boyd was my mate, my friend, my confidant. I trusted him and he trusted me. But in a difficult spot on the battlefield in Fire Emblem, I realized that Boyd wasn’t going to make it. He was cornered by knights, no way out. And after a few more turns, the damage was done. The character I had since the beginning was killed.

I felt terrible. Awful. He didn’t have to die – the game didn’t have any requirement that he not make it through the battle. It was my fault, needless bloodshed. He was a good, strong character with some good weapons and armor, but now he was gone.

Throughout the rest of the game I was reminded of my mistake. His brother would say, “We can do this! It’s what Boyd would want.” His friends would chime in, “If only Boyd were here, he’d know what to do.” I’d go into battle thinking how useful he would be, but he was gone. Heck, this game is almost 10 years old now, and I still remember it, despite not remembering the name of a single other character in the game.

My experience with Boyd, a virtual character afflicted by a virtual choice, taught me as a game designer what it is to create a “meaningful choice” in a game. Choices that pull at players heart strings, that make them look deep inside themselves at their own character in real life, that they remember as deeply emotional experiences. These are the designs that turn a game into art.

But how do you do it? How do you make a choice in a game truly meaningful?

Rather than take my word for it, let’s learn from the masters - 2012’s critically acclaimed Walking Dead, which I personally believe that this game is the current state of the art.

What Is Meaningful Choice?

This is one of those “are games art?” type questions that everyone has an opinion on and discussions go on forever. That’s fine, there’s room for opinion.

But for my designs and for this article, I define meaningful choice very specifically.

Meaningful choice requires the following four components:

Awareness - The player must be somewhat aware they are making a choice (perceive options)

Gameplay Consequences – The choice must have consequences that are both gameplay and aesthetically oriented

Reminders – The player must be reminded of the choice they made after thay made it

Permanence - The player cannot go back and undo their choice after exploring the consequences

If all four of these requirements are satisfied, then we have a recipe for meaningful choice. The reason that this is true is that these are the components of a meaningful choice in real life.

Think of the big decisions you made in your life - where to go to school, whether to tell on your friend, who to marry, whether to break up - all of these choices have these four components. And these are the choices that make up our lives.

In games, choices with these components will evoke a strong emotional reaction, something that players discuss and think about and remember. By making the choice meaningful, we help to make the game itself meaningful.

Let’s step through each of these four components in detail.

Component 1: Awareness

If the player isn’t aware they are making a choice between two or more options, then it isn’t meaningful.

Imagine that a player is in a game where a character named Cindy is crying for help. The player runs over and helps Cindy. At that moment, the game says, “You choose to save Cindy instead of Bernard.”

But the player never saw Bernard. They didn’t even know Bernard was in trouble, or that he even existed. At this point, the player would probably feel frustrated. This ruins the choice and makes it meaningless. Instead of feeling responsibility for any consequences of the choice of Bernard vs. Cindy, the player will instead blame the game. “What?! I didn’t know I could save Bernard! I didn’t even want to save Cindy!” It’s no longer viewed as any kind of choice, and anything that happens as a result will be viewed as inevitable.

Second, the player completely misses the experience of having to think, agonize, and decide what they would like to do themselves instead of what the game is telling them to do. If the player isn’t aware they are being presented with a choice,

The Walking Dead handles the awareness of choice through its choice interface largely pioneered by David Cage in his games Heavy Rain and Fahrenheit. Most of the time when a player is presented with a choice, they can clearly see the other options.

Exactly how much awareness you give the player is up to you.

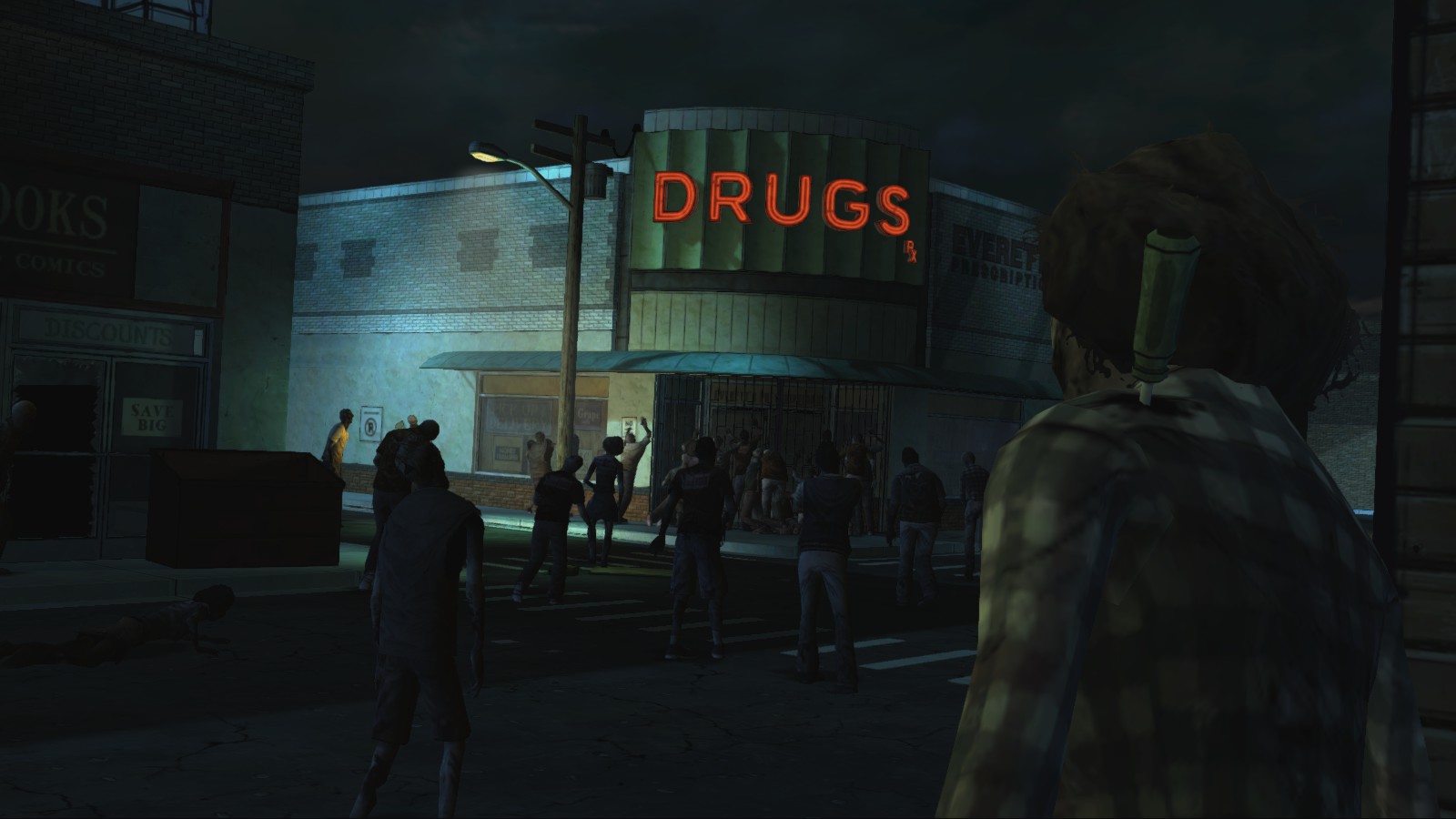

In the Walking Dead, some choices and their consequences are obvious. A situation very similar to the example above, the player is hiding out from the walkers in a convenience store. A group of walkers breaks into the store and two characters are grabbed, and the player must choose who to save.

The player is given plenty of time to make this choice, and both characters are in the player's field of view. This makes the fact that it is a choice obvious, so when the player picks one, they feel responsible.

The level of awareness of a meaningful choice can vary, however, long as the player knows they are making an explicit choice.

As an example, In a conversation with Hershel at the beginning of the game, the player is asked a number of questions, “Where did you guys come from?” “Are you her father?” “Who did you come here with?” It isn’t exactly clear which of these questions are significant and which aren’t. However, the player is still aware that they are making choices, even if they aren’t sure what the consequences will be. The interface for conversation makes this clear - the player is never presented with one response - always two or more.

So when Hershel catches you in conversation or in a lie, then the the player feels like it was their fault. They saw that they could say, "I was alone" versus "I was with a police officer", and so when Hershel reprimands them, they know that it was their decision.

Component 2: Gameplay Consequences

Imagine you’re playing a game and you get a treasure chest. Inside the treasure chest there are two items:

A new sword that is more powerful and will defeat two-hit enemies in just one hit

A sword that acts the same, but it’s a different color than your current sword

Which would you want? Obviously you would want the first sword, because it has gameplay consequences.

Gameplay consequences don’t just change the signs and sounds of the game, they actually change the behavior and actions of the player. They don’t just make the game look different, they make it act differently.

The best meaningful choices have both aesthetic AND gameplay consequences. Changing the experience of the game, the behavior of the player, is typically more meaningful than just playing the same game with different set dressing.

In the Walking Dead, there are numerous gameplay consequences from the player's choices. Deciding to back up Kenny in a fight he's having with Larry affects how he feels about you. In a fight in the convenience store, backing up Kenny means that later he helps you when you get into a scuffle with Larry. It also affects whether or not he decides to go along with your plans.

True to the premise of the games, the choices you make have ripple effects until the final episode is complete.

For a poor example of gameplay consequences, one of the more recent games in a narrative genre dealing with meaningful choice was David Cage's Beyond Two Souls. In contrast to the critically acclaimed Heavy Rain, Beyond Two Souls drew scorn from many players and reviews (Score of 71 Metacritic, versus 87 for Heavy Rain and 92 for Walking Dead). While the graphical effects were phenomenal, the gameplay seemed by many to be lacking.

Kyle Orland from Ars Technica wrote:

I rarely if ever stopped to consider a choice in Beyond: Two Souls...Instead, I mainly sleepwalked through a seemingly endless sequence of practically preordained story beats, struggling to care as I was dragged through a clichéd plot with no sense of meaningful agency.

Making a choice of whether to talk about Ellen Page's dress versus the guests has no result other than changing the dialog for that line. The rest of the game is the same.

By using the framework for meaningful choice, we can make a hypothesis of what was wrong with many of the choices in Beyond Two Souls: they didn't have strong enough gameplay consequences. While it's all conjecture, perhaps if the team at Quantic Dream had improved this, maybe the decisions players made would have felt like they had greater emotional weight.

Component 3: Reminders

Regret is a very complex human emotion. The regret of letting old friendships slip away. The regret of having worked too much and not spent enough time with family. The regret of having never went for your dreams when you had the chance. Regret is the combination of disappointment and responsibility, the sadness that comes from the present not working out as you wanted because of choices in the past.

Pride is the opposite of regret. Pride is when you feel elated because of a choice you made that has resulted in the outcome you wanted (or better). It’s being proud that you decided to marry the person you love. It’s being proud that you chose one job that turned out great. It's being proud that you made the right decision.

These stories of regret and of pride are the stories that make up our lives.

However, if you don’t remember your previous choices, then you will never feel pride or regret. Or if your previous choices don’t affect your present world, then you will similarly not feel anything.

In Walking Dead, the player is constantly reminded of choices that they made in the past. “You never backed me up!” yells Kenny. “You weren’t able to protect her at the Motor Inn”, says another character later on in the game. The choices that you make not only affect the moment, but the long term relationships that you have with other characters. If Telltale hadn't put these reminders in, then many of the choices would have meant nothing to the player.

By sprinkling reminders through the game of what choices the player made previously, the choices take on more and more weight. As the player goes forward in time the same old choice affects more and more of their experience, imbuing it with meaning. If you made your choice and then went on without even remembering it, you would never later feel regret or pride. You’d just feel nothing.

Component 4: Permanence

At the end of Paper Mario and the Thousand Year Door, the final boss asks Mario if he would like to turn evil and join their side. The player can choose yes or no.

If you select yes, the final battle commences. However if you choose no, then the player simply gets a “Game Over” screen and is reset about ten seconds backward.

No one talks about this as being an incredible ending that reveals something about your own moral fiber. If they remember it all, they talk about it being annoying. The fact that you can go back and change your outcome immediately turns what could be interesting gameplay into a boring formality.

The reason that choices in real life are so fraught with emotion, with sadness, with purpose, is because they are permanent. We can’t live our lives over again. In real life, you can’t have a fight with your significant other and then rewind and do it again. You only get one shot, which is why you need to choose your words and actions very carefully.

And yet in games where you can reset, you have no problem blowing up buildings or attacking innocent bystanders with no hesitation.

Walking Dead handles this by using autosave functionality. As soon as the player makes a significant choice, the game locks it in so that they cannot go back. Thus, with every choice you make, you need to be sure it’s what you believe.

Sure, players could restart from the beginning or reset the episode, but the added inconvenience is usually enough to deter them.

Conclusion

I hope this framework is useful to others. If you can make sure your choices in games have all four components, then I believe they will carry enormous value to players.

As I mentioned earlier, there are likely thousands of variations and permutations on how to create meaningful choice, this is just one that has been helpful to me that I see over and over again in successful games.

I do believe that games are art, and the deeper games can probe into emotions normally reserved for film and literature, the better. By making games that cause players to make choices that cause them to evaluate their character as a person, to take the lessons of the game and apply it back to their real lives, we as game developers will have done something very special.

Choose wisely!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author

You May Also Like