Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Legends of Runeterra #2: A dive into its gameplay

In-depth gameplay analysis Legends of Runeterra, the CCG by Riot Games.

It explores its mechanics, the mechanics of its closest competitors, how the game has solved their problems, and which are its key innovations.

Welcome to our second article on Riot Games’ Legends of Runeterra collectible card game. This time we will be focused on analyzing its gameplay — as well as its competitors’.

In case you haven’t checked out our other posts about LoR, here are the links:

In the first article, we reviewed the CCG market status (as of June 2021), focusing on Runeterra’s position and growth perspectives. Read it here.

This article will explore its gameplay mechanics, how the game has solved the problems of its closest competitors, and we will also discuss its key innovations.

Note that we won’t be dealing with the different game modes in this article. That will go in the next one, as we consider it more related to its content management. Here we will talk exclusively about what happens inside the match.

And the last one will look at its content management strategy and how it might affect its long-term engagement. It will also include our POV on if their approach can work or not.

Before going into the deal, I would like to give special thanks to my editor Victor Freso. He helps me structure the content so that it’s not a bunch of mad ramblings. And of course, remember that we are not affiliated with Riot Games in any way. These are just our thoughts as fans.

Breaking down LoR gameplay

In our previous article, we explained how Legends of Runeterra suffers the handicap of entering the digital CCG market at a moment where it’s pretty crowded. It’s competing with games that got a significant early advantage in market penetration.

When it comes to gameplay, on the other hand, it benefits from being a latecomer.

As a short description, we could say that LoR is a fast and aggressive mix of Hearthstone and MTG.

It cherrypicks most of its core design from Hearthstone and adds elements from Magic: The Gathering to go beyond the design limitations in Blizzard’s game.

Of course, we are not blind to the fact that LoR also adds new mechanics and ideas which aren’t present in neither of them. And some are incredibly game-changing (like the fragmented rounds). We will talk about those unique characteristics in detail later in this article.

But before that, we think it’s essential to look at Hearthstone since many design decisions in LoR were heavily influenced by it.

Hearthstone: A milestone for digital CCGs

We feel it has often been underestimated how revolutionary and important was Hearthstone to the CCG genre. Specifically on adapting and streamlining the core gameplay mechanics from the tabletop to a digital platform.

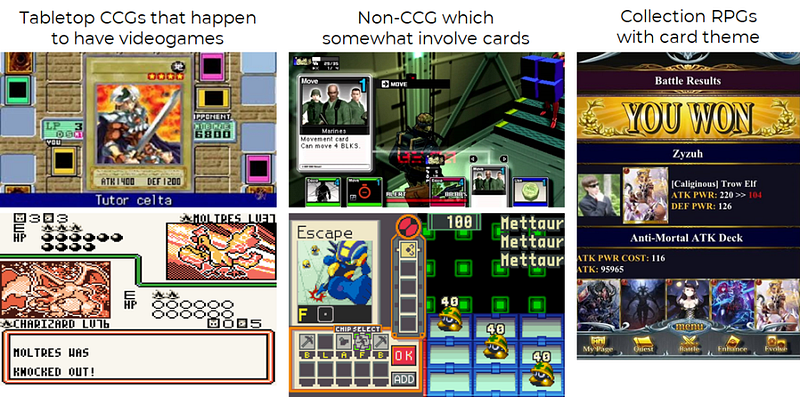

Before Hearthstone, most digital card games fell under any of these categories. They either weren’t explicitly designed for a competitive card game experience or struggled with tabletop mechanics, which don’t avoid the limitations or explore the unique opportunities of videogames.

Hearthstone was the first game to reach massive appeal that aimed for a competitive CCG experience while being 100% designed as an approachable videogame.

To improve overall accessibility, it decreased complexity and accelerated the gameplay, allowing a space-efficient visual presentation and also using new game mechanics available only on a computer-driven experience.

This is better seen in the following design decisions:

1. Having a strict mana curve

Although fun and spicy, resource generation represent a lot of complexity and friction on many CCGs: Either because it requires significant math probability juggling when deckbuilding and playing (Magic, Pokemon TCG…) or because it involves custom sacrifice systems (Yu-Gi-Oh, Legend of the Five Rings…), which are as complicated.

And, perhaps more importantly, it makes it very hard to predict the game’s tempo, since designers can’t have certainty when a card becomes playable.

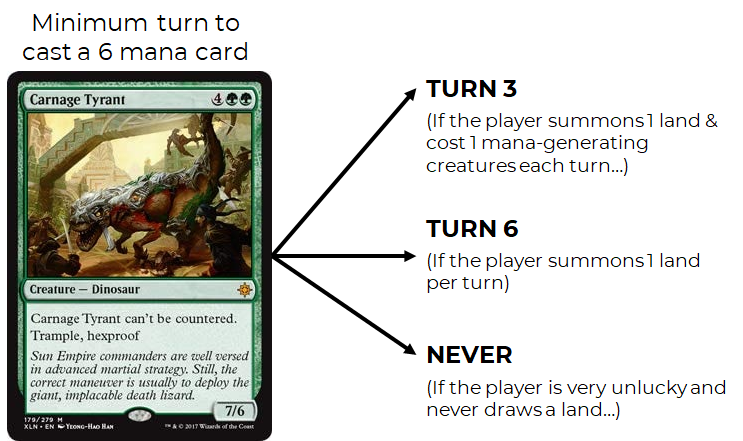

In MTG, resource generation randomness means a vast disparity of possible scenarios, making balancing much more difficult. And this example is not even taking into account the complexity of having multi-colored mana.

To simplify this, Hearthstone took a Solomonic decision:

Each turn, players automatically get one more mana than the previous turn. End of the story. They also removed multiple types of resources (contrary to MTG or Pokemon, where there are several color types), which simplified the whole process.

Additionally, in contrast with MTG, they have very few cards that accelerate the mana curve and no “resource generation” minion.

In Hearthstone, resource acquisition is strict and predictable (+1 mana per turn, only one type of mana). This makes balancing way easier to control. In contrast, in MTG the mana is highly affected by randomness, and bad luck can generate frustrating situations where the player can’t play at all.

Was simplifying mana generation a good decision?

My personal opinion is that complex mana dynamics in MTG is part of what makes it attractive for a wider audience: By being lucky, a bad player with a bad deck can be challenging to an expert with a better deck. And it makes that experts need to strategize around that uncertainty.

The most exciting moment at MTG is when you draw the mana that you desperately needed. And the most frustrating one is when you desperately need a land, and it doesn’t want to appear.

So it is both the best and the worst of the game. And therefore removing it takes away frustration but at the cost of losing something extraordinary.

Additionally, the complexity of mana in MTG generates deep mechanics based on the resource curves accelerations possible (for example, in mid-range decks).

That said, I think that random land drawing it’s a mechanic that feels much more frustrating in digital CCGs:

First, because they focus on single matches rather than in the best of three, the main competitive model on tabletop MTG.

And second, because on the tabletop is the player itself shuffling: bad luck can’t be externalized as someone else’s fault. While if it’s the RNG shuffling, bad luck is the game’s fault.

For that reason, even MTGA is experimenting with altering the probability system in some modes to favor the appearance of mana in the opening hand, which avoids the worst case in randomness (a player not being able to play at all).

Because it’s more frustrating on digital, it makes balancing much harder, and it’s a significant entry barrier for new players; I believe that it was a good call to simplify the mana system in Hearthstone.

If anything, the only problem I could see is that perhaps it was too strict since it removes any gameplay depth around mana generation.

Colorless mana and Hero Classes

In MTG, mana colors also serve as a balancing control mechanism. They establish groups of cards that can’t be used together on the same deck, at least not with a significant effort (multicolored lands, etc.).

So Hearthstone introduced Hero Classes to achieve that same objective: Most cards are exclusive to specific character classes, making balancing much easier. (LoR has more or less followed a similar approach by limiting the amount of Champions and Regions in decks).

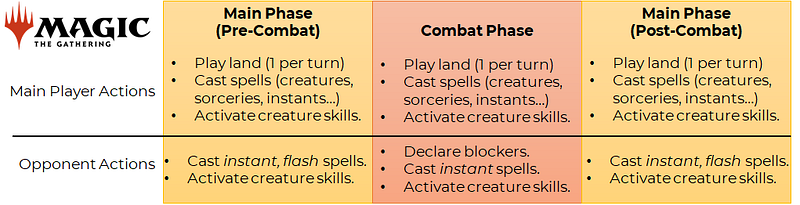

2. Removal of turn phases where the opponent interacts

One of the main ways this is achieved is by not having any kind of instant or answer spells that interrupt the opponent’s turn or counter an action. As well as by having no units with player-activated minion abilities.

This means that the game doesn’t have to wait to see if the opponent will answer constantly. And it dramatically decreases the viability of control decks, which slow down the game and aren’t very friendly for newbies.

Blizzard also removed the opponent’s ability to assign defenses on an incoming attack: In Hearthstone, the attacker determines the unit encounters during an attack. The defender may only passively limit the choices through units with Taunt.

In MTG, there are several actions that the opponent can perform at any moment. In the videogame, it means constant timers to check if the enemy will act. Any of these actions can trigger a chain of answer & reply spells between players.

Ultimately, all this makes Hearthstone faster since all those opponent answers meant many delays in the progression of the match, timeout timers, etc. And it removes turn phases, which also makes the overall game easier to learn.

3. Tokenization of units (less unit orthogonality & survivability)

Hearthstone also decreased the cognitive and visual load of having multiple orthogonal units on the battlefield. This is achieved in 3 main ways:

First, by creating units with less gameplay depth:

Compared to MTG, Hearthstone features fewer cards with specific rules. Instead, it focuses on standardized abilities shared by multiple characters (i.e., windfury, lifesteal…), transformed into recognizable icons and FX.

This allows removing a lot of card info when they are on the board, as it becomes redundant, again decreasing the visual and cognitive load that a minion represents.

A factor contributing to this is that sets in Hearthstone don’t tend to be built around a new keyword mechanic (which is the case in MTG). This means that the complexity of minions doesn’t grow as much when more sets are released.

Ultimately, most minions with unique behaviors trigger them either on summon or on death or have triggered effects that generally less complex than MTG’s. Additionally, Hearthstone doesn’t feature player-activated creature skills.

Creatures in MTG often feature complex and unique behaviors which generate many chances of emergent gameplay. Most Minions in Hearthstone have effects on summon or on death, or simpler rules which usually take a smaller amount of text.

The second way how minions become more dynamic is by decreasing their survivability:

Minions don’t regenerate their health at the end of the turn (a computer has no problem keeping track of the individual health of every unit).

This means that even the tankiest creatures won’t remain for long in the field, as critters can slowly eat up their health. Therefore, it means fewer chances of having many different minions on the table simultaneously, making turns faster.

And last, by adding a hard limit on the number of creatures that a player can have on the battlefield (7 minions max). Although, because of the lack of regeneration, the creature limit is not often reached.

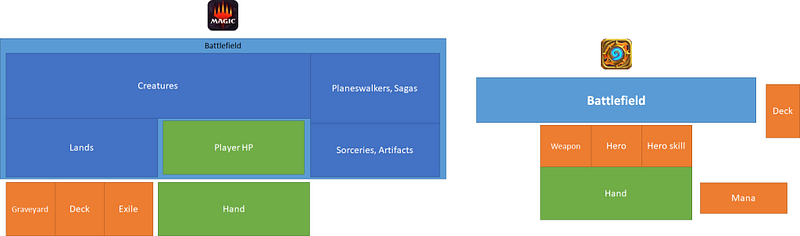

4. Less amount of game elements

On top of simplifying the minions, this game aims to be easier to learn by decreasing the number of different types of cards, game zones, and playstyles.

First, there’s the topic of the number of game zones:

In Magic: The Gathering, there are many of them (battlefield, graveyard, exile, player hand…), each with its own specific rules. Also, many cards interact with the opponent’s zones, which means even more areas to keep track of.

While this offers many gameplay possibilities, it also makes it overwhelming for a new player and requires more UX effort to make it manageable.

Meanwhile, in Hearthstone, there’s no graveyard or exile. The only card zones are the hand, the battlefield, and the deck. And the amount of cards that interact with the deck or the opponent’s hand is minimal.

The same happens with the types of cards:

MTG features many different card types, including creatures, sorceries, instants, enchantments, equipment, lands, planeswalkers, and many more, each with its specific rules.

The amount is way higher if we consider the types specific to some sets like Sagas, Companions, Vehicles, Food… the list goes up to +26.

In contrast, Hearthstone only has 5: Minions, spells, secrets, weapons, and heroes, with the first two agglutinating most of the cards and mechanics.

Ultimately, this means fewer specific rules to keep in mind, making Hearthstone easier to learn and present on a screen.

Wireframe comparison: Notice how Hearthstone has fewer elements to represent on-screen (game zones, types of cards…). This makes it easier to learn by players and is easier to present on a single screen.

The problems of Hearthstone’s design

It’s beyond doubt that the changes introduced by Hearthstone helped its adoption by massive audiences. But as hinted above, they also introduced several design dead-ends that have not been fixed despite some workaround mechanics.

In our opinion, the most important of those issues can be summarized in:

ISSUE #1: Simplification means less gameplay depth

Since the big move of Hearthstone was to have a lighter core ruleset, it also means less repertory of rules to create innovative gameplay. This translates into two main problems:

Limited range of available strategies

Because of many gameplay elements that interact between them, MTG has decks built around bizarre strategies, such as casting from the graveyards or playing in the opponent’s turn (control & flash decks). It also features a considerable amount of combo decks.

This creates a lot of variety, creates many different ways to play the game, and provides an incentive for expert players whose challenge is not simply winning but using a crazy specialized technique.

Because I’m a petty person, this was my favorite combo in MTGA (last rotation). I swarmed the table with critters while taking damage, and then I attacked with the boosted Chandra Spitfire. As the final timer went down while the other player realized that the match was over, I swear I almost could hear the sound of a table flipping on the other side.

Contrary to that, in Hearthstone, there are only a few strategies available, all of them entirely dependant on tempo (aggro, midrange, and control), and there is little room for decks that deliver unorthodox strategies.

While this makes the game easier to balance and playtest, it also means that it’s more repetitive and predictable. Hearthstone allows many deck tunning, but it’s impossible to find truly innovative strategies, and therefore the game is a bit less appealing for experts.

Less variety in new content

Another of the problems is that new content is not very game-changing or innovative.

It relies on new cards that rebalance the meta that is already there (i.e., more power for less cost, add a card that cancels a current meta-strategy…) rather than introducing truly innovative mechanics.

And when new mechanics are introduced, they generally focus on very contained dynamics, which can’t generate synergies with many points of the game but rather a particular set of combos.

This is a good tactical decision: It makes new sets easier to playtest and less costly to develop. Therefore it allows a smaller design team to manage Hearthstone.

For example, the latest Hearthstone set introduced Frenzy, which has a limited impact on the overall game. Although it’s on the Warrior meta, it primarily affects specific classes and cards, so it has little chance of getting out of control because it’s a quite situational. In contrast, in Throne of Eldraine, MTG introduced adventures, which impacted all deck strategies and colors, and had more potential for emergent gameplay (grants card advantage).

Don’t Computer-driven and randomness mechanics fix this?

To avoid being too plain, Hearthstone added new game elements that enrich the gameplay.

To achieve it, it embraced mechanics that required a computer-managed game experience, taking full advantage that the game has no tabletop equivalent.

For example, the computer can handle complex random calculations, keep track of past events, or act as a referee validating secret actions that an opponent can’t see.

Some examples of cards exploiting computer-only features which would be hard to bring to a tabletop experience. Among them, the most common is the use of randomness.

Out of all of these computer-exclusive mechanics, randomness has become the trademark of Hearthstone’s gameplay.

One of the main reasons is that randomness is streamer friendly: The moments that cause the most impact in HS are when randomness generates something amazing or frustrating.

Summoning Yogg-Saron is always a streamable moment, as a massive amount of random spells with random targets are cast in sequence.

But, while in some cards, it fosters interesting dynamics built around diminishing their unpredictability, randomness doesn’t create alternative strategies that move the player to play in a radically different way to achieve victory.

ISSUE #2: Lack of answer mechanics

By removing all actions from the opponent during the other player’s turn, Hearthstone grants the active player absolute certainty of its results, making the turn predictable (unless there are secrets, but even that has workarounds). It means that many decks are played on autopilot.

This makes the gameplay sequence fast and accessible but not emotionally intense.

In MTG, answer mechanics (activated skills, instant spells, block assignation…) introduce risk management, one of the game’s most fun dynamics. It creates a complex social interaction between players, which is similar to poker:

For example, on any given play, players need to consider how much unspent mana the enemy owns, the number of cards in her hand, and more, and ultimately judge if the opponent will counter the incoming maneuver.

And, of course, the opponent might be just bluffing by deliberately leaving unspent mana and forcing pauses.

In MTG, an appropriately timed instant spell can completely change the outcome of a match, causing some of the most emotionally intensive moments in the game.

Don’t Secrets fix this?

For those unfamiliar with Hearthstone, secrets are spells that trigger when a particular condition is met. For example, When the Player Hero takes damage or When the enemy casts a spell. Untriggered secrets are seen as an indicator on the owner’s Hero.

Secrets are an attempt to solve this issue by adding a passive answer system to players. But, while secrets are an interesting game mechanic, they are not an effective way to reply or counter the opponent’s actions:

First, they need to be cast beforehand by the player and are visible. Only the conditions and effects are hidden.

This means that if there’s no secret previously cast, the player knows that the actions won’t be countered.

While in MTG or LoR, the menace it’s always there and may force the player to adapt the strategy and avoid the most damage-effective approach.The second issue is that the owner can’t choose if they trigger or not. Therefore, it removes the possibility of delivering a coherent answer: A secret can activate at a point where it doesn’t necessarily bring a meaningful advantage for the caster.

Also, if there’s a secret cast, the opponent can attempt to defuse it. For example, by attracting its effects to a lesser minion. This is relatively easy to do because:

1) Most secrets have wide range trigger conditions (otherwise, they’d be too situational and therefore useless).

2) The range of possible secrets of a specific cost that are viable in the current meta, specific class, and deck can be limited, allowing the player to make an educated guess on which secret has been cast.

So what does LoR take from Hearthstone? What does it add?

#1: Everything has an answer

So we just saw how one of the big issues in Hearthstone is that the active player barely interacts with the other during the turn. That makes that many strategies can be played on automatic expecting predictable actions from the enemy, based on her class.

In Legends of Runeterra, on the contrary, almost every single action allows the opponent to answer. This is mainly because of 3 game mechanics:

Fragmented Rounds

IMHO, this feature makes LoR stand out as the most dynamic digital CCG, generating constant action-reaction interactions between players.

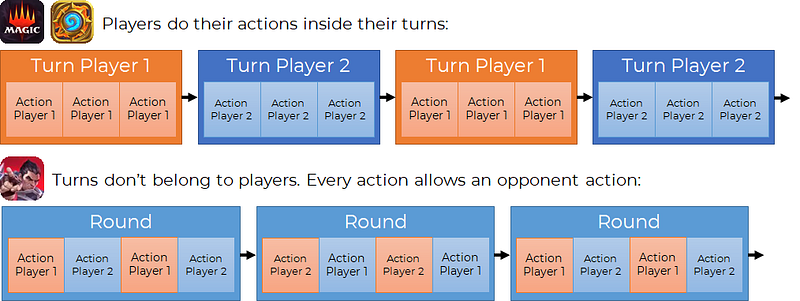

Instead of segmenting the game in turns where the active player can perform a whole series of actions, in LoR, the gameplay is divided into mini turns.

On each of them, a player can perform a single action. And then the opponent does. This goes over and over until both players run out of actions and pass, starting another round.

This means that the player has the chance to answer every single action of the opponent without special cards. Even non-control decks allow players to adapt to what the enemy is doing and counter the specific combo they may be building.

Contrary to MTG or Hearthstone, where each player has turns where the active player performs several actions, on LoR there are only mini turns where players can only perform a single move. Then it’s time for the opponent to answer.

Additionally, the ability to attack (represented in the Attack Token) changes between players on each round, which means that players switch between offensive and defensive rounds.

This creates a very engaging dynamic where the attacking player has to judge when it’s the best moment to perform the attack: If she spends turns summoning or boosting followers, she allows the opponent to build up defenses.

In some cases, the best approach may be to just attack at the beginning of the turn without allowing the opponent to summon more defenders.

And, of course, there are several more situations like this: Doing any build-up action means giving a chance to the opponent to answer.

For example: In this situation, I could safely attack now since the enemy has no followers to block. Or I could summon another unit for a more powerful attack, but then I risk the opponent summoning defenses.

As you can see, the fragmented round structure introduces an element of gambling on every decision taken. And it takes away most of the tempo advantage of the first turn, which is a significant problem on other CCGs.

Additionally, because the mini turns are so short, it means that the match is also more intense since players can’t take their eyes away from the game or relax, as control will come back to them soon.

To summarize, this is a fantastic mechanic.

Counters & Quick Spells

On top of the turn structure, which fosters action-reaction situations, Legends of Runeterra also allows answering to spells, similarly to MTG but a bit more under control.

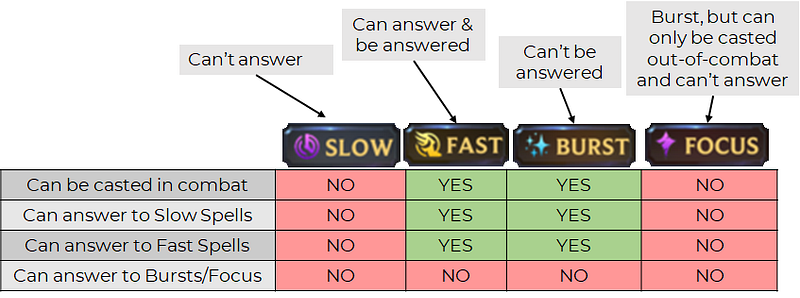

Spells have a speed based on their type. Faster types will take priority on the stack of casted spells. Interestingly, to avoid complex stacks with dozens of spells, there is a hard limit at 10 (although I’ve never seen it reach there in a match).

Spells in LoR are structure around speeds: Fast spells can answer Slow ones, and Bursts can answer Fast Spells and is unstoppable. Focus is a mix (it’s instant but can’t be used in combat, or as an answer), and there are also Skills that can belong to any of the previous speeds. It’s an effective system but a bit unnecessarily complex for a new player.

An important detail here is that spells are the way how LoR manages a creature’s activable skills. Instead of interacting with the card, followers with activable skills create skill spell cards on the player’s hand.

It is a smart way to create complex abilities without overloading the card with info.

My personal opinion is that the basic spell answer feature it’s reasonably understandable (burst is immediate, fast outpaces slow). Still, it becomes harder to grasp when it deals with skills and focus spells outside the speed model.

Although I can deal with it without problems, I could understand how this might be a strong comprehension barrier for inexperienced players.

Attack Positions & Blocking

Another point where LoR goes in the direction of MTG is by allowing the opponent to assign defenses, which definitively breaks the playing on autopilot problem of Hearthstone: Both attackers and defenders need to plan their actions in combat carefully.

Although, as a twist from MTG, the battlefield is segmented into six combat lanes, each of which can have only a single attacker and a single defender.

This means that a player can’t use multiple critters to block a single tanky follower, killing it by attrition.

LoR battlefield is segmented into six slots on each side. This generates interesting mechanics, as combats are resolved from left to right: Block assignations need to exploit this to foster any useful effects (setting last in order a follower that gets stronger with every dead unit, for example).

Interestingly, this lane segmentation also applies to the bench: LoR allows only 6 summoned units on each side, which is a limitation even more hardcore than Hearthstone and happens way often.

This brings additional depth: If players fill all the slots will weaker minions, they will have to replace them with the stronger ones. And summon effects won't work.

(Thanks Shadoria for correcting this point).

Ultimately, I think this attack lane approach is a nice paradigm that makes attack blocking much easier to understand (as it is very visual) and adds a bit of extra depth.

Interestingly, LoR also uses the lanes structure to generate gameplay depth. Some of the effects interacting with card positioning are standard, such as cards that switch positions once blockers have been declared. But some are a bit unorthodox:

Support cards boost the attacker located to the right. I felt this design was original but also hard to grasp. It took me several matches to understand it.

I can think of more possibilities to use card positioning and lane structure to create exciting mechanics, such as cards that occupy two slots or critters that fit in one.

Although IMHO, this kind of disruptive element would be better in the future, once the game has enough userbase that has learned how to play with a more traditional approach.

#2: Stored Mana: Strict mana curve with a twist

Earlier, we mentioned how Hearthstone simplified mana generation to improve the adoption by new players and make it easier to balance by a small team. And how this had the handicap of removing all gameplay depth around it.

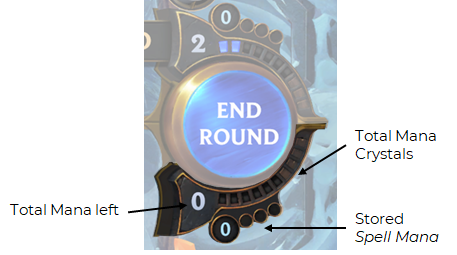

LoR also takes the same system, but it adds a twist that adds extra strategy: Players will save up to 3 points of their unspent mana, which can be used to cast spells.

Up to 3 unspent mana crystals are stored to cast spells (although it can’t cast other card types).

Using this, players can slightly affect the early mana curve, perhaps to build up a combo on the next turn. But because the mana can’t be used to cast units, it’s more challenging to apply it to midrange decks (which would be highly unbalancing).

It also makes it less punishing if the opening draw leaves players with no actions on turn 1: they get a small advantage instead.

I think this is an elegant design that delivers gameplay depth while avoiding a drastic change that wasn’t needed (or that wasn’t affordable, since more complex mana dynamics would mean more balancing effort and a bigger team).

#3: Champions: Increasing the range of strategies

So far, we’ve talked about the many answer mechanics in Legends of Runeterra. Now it’s time to speak about orthogonality.

We saw how Hearthstone barely features any combo deck and focuses on 3 monolithic strategies (aggro, midrange, control) instead.

On the contrary, many decks in LoR are combo decks. And they’re built around special units which are extremely orthogonal (game-changing), called Champions.

Nasus decks are based on self-sacrificing units to boost Nasus, and then kill it with the Atrocity spell to destroy the enemy in one shot.

Fiora decks are based on making her accumulate kills while helping her survivability through Barriers.

Alternatively, Champions may boost a non-combo deck through powerful synergies.

Like in the case below, which delivers an accelerated mid-range strategy:

Lurk units get +1 when there’s a Lurk card on top of the deck. By attacking and returning to the deck, Rek’Sai boosts Lurking allies into killing machines.

Because they’re extremely powerful, there is a set of limits in terms of deckbuilding:

There can only be 6 champion cards on a deck. This limitation goes on top of the fact that decks can only have cards from 2 regions and can only have 3 copies of each card.

This means that, in theory, a deck could have 6 different champions since each region has ~7.

But there’s no benefit in having many different Champions in a single deck since that means that the rest of the cards can’t be optimized to build a specific combo and lowers the chance to draw the desired one.

Consequently, most decks naturally focus on carrying the maximum possible copies of only 2 Champions: the primary one for the combo and another which serves as synergy or utility.

Leveling Up Champions (A streamer friendly moment)

An interesting concept about Champions is that they transform into a better version when a specific Level Up condition is met.

In some cases (like Fiora shown above), that level up is an intrinsic part of their combo, while on others (Nasus), it’s just a bonus that can become a side objective to help snowball the game.

Sometimes the conditions are fairly specific, which forces the player to adapt their deck and actions to achieve it. Often, this generates meaningful decisions (doing actions that are suboptimal in the short term but optimal in the long), as well as and opportunities for the enemy to counter.

Interestingly, this is a different take on computer-driven mechanics:

Instead of exploiting the capacity of the computer to generate randomness (some cards use randomness but in a much more limited way than Hearthstone), LoR exploits the ability of the game to record past events to generate objectives during the match that empower the strategy.

And for bonus points, the concept of Champions that level up is centric to the League of Legends IP since a big part of the MOBA experience is based on that.

An interesting characteristic is that conditions to level up a Champion increase even when it hasn’t been summoned, unless stated otherwise. This makes decks orbit around Champions even more.

I wouldn’t like to miss pointing out how much effort is done to make Champion level-ups feel spectacular.

I’ve often seen game developers think that a “ready for eSports” game means that it is competitive. But it goes beyond that: It also means that the game is fun to watch.

An eSport is not only a competition. It’s also a show.

IMHO, one of the things that make League of Legends great for watching is that it has decisive moments that generate an emotional impact for both players and the spectators:

Things like destroying an Inhibitor, killing the Baron Nashor, or the outcome of a team vs team fight. Epic situations that mean that a team has achieved a (potentially) decisive advantage.

It’s like in Soccer: The most spectacular moments in a match are the goals (when they’re about to happen when they are scored, or avoided…).

So if the Soccer match finished as soon as the first goal is scored, the game would be competitive but not as fun to watch, as it would have fewer of these exciting moments.

Watching soccer on TV would also be way less spectacular if goals weren’t followed by an exciting celebration from the crowd in the stadium and commentator.

Meaning that a game that wants to have the potential for eSports has to be designed to include those decisive moments and the means to highlight them spectacularly.

In LoR, those spectacular moments are the Champion level-ups, which usually mean that the player has achieved a potentially decisive advantage.

The emotional reinforcement effect of the animation is powerful for players, and it will be helpful when Riot Games builds a big eSports scene for Legends of Runeterra.

It’s easy to foresee a moment where a player achieves a level up that changes the game’s course, and the commentator and the crowd scream as an epic animation plays out.

Additionally, the level-up animations could eventually become cosmetic products. For example, by adding additional value to card skins (i.e., getting a different card picture adds a custom level-up animation).

#4: Keyword Effects: More Orthogonality (Too much?)

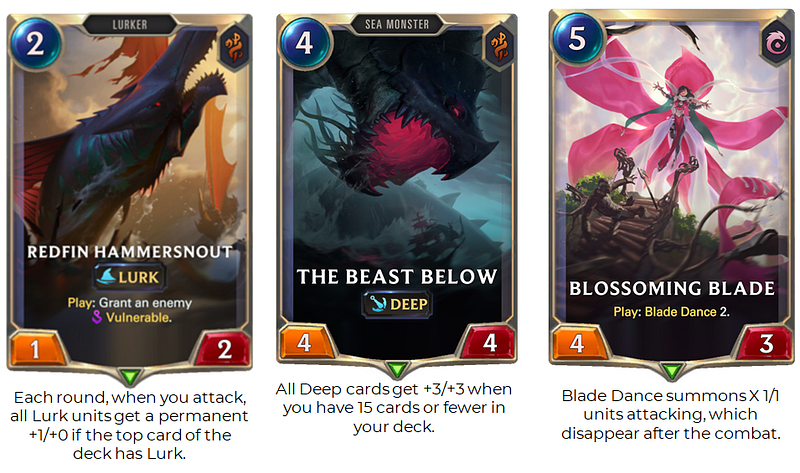

The second element that generates card orthogonality in LoR is the Keywords. Same as Hearthstone, they’re card mechanics that have been summarized to avoid long card texts.

A point to highlight here is that many LoR keywords are incredibly original.

In Hearthstone, many keywords can be related in one way or another to standard abilities or triggers already existing in MTG (i.e., Rush & Charge are versions of Haste, Windfury is kind of Double Strike, etc.…).

Additionally, because the deck strategies are related to specific champions and keywords, they generate very innovative gameplay dynamics, which I haven’t seen in other CCGs.

Some examples of my favorite keywords (although there are many):

Many keywords in LoR generate unique ways to play the game. For instance, Lurk decks focus on dynamics that return cards to the top of the deck, something rarely seen in other CCGs. And Deep decks aim to toss as many cards from the deck as possible, which would be negative in most other games.

Overall, we believe that out-of-the-box keywords create a refreshing and engaging experience for seasoned CCG fans. That’s good. But too much of something good can harm you.

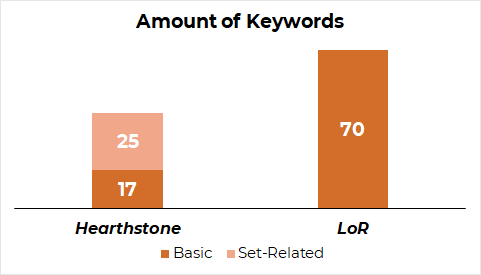

Too many keyword mechanics

If originality is the first thing we noticed about keywords, the second is their quantity: There are A LOT of keywords. Part of the reason is that many of them are related exclusively to certain deck archetypes and specific champions.

LoR features a significantly higher amount of keywords than Hearthstone. While this offers a lot of variety, it also makes the game harder to learn and means that some of those keywords are ignored.

While at first glance this may seem entirely positive, as it provides more varied gameplay, IMHO, in the end, it has a bad tradeoff:

It makes the game harder to adopt by players (meaning it will damage early retention), and it makes several of them fillers, as they are not valuable for competition.

The issues of LoR gameplay

Please note that this last part is highly subjective. It is not an attempt to tell the ultimate truth but rather to share our own ideas as fans. So don’t bash us if you disagree! Let us know YOUR own thoughts on this topic : )

Before starting this section, we would like to clarify that we don’t think that gameplay is a significant issue in LoR, especially after the last updates have diversified the meta.

The real challenges are more related to the in-game economy and a lack of progression and collection, but this is another topic that we will cover in our next and last article.

The points below, all related to gameplay, could be improved, but ultimately we think they are not critical. We might change my POV if I saw the early retention KPIs and onboarding funnel, though.

And all of them are definitively solvable through new content and a rotation system that sometimes they have hinted that will come eventually.

#1: Too many mechanics

In combination, Champions and imaginative Keywords allow LoR to go beyond the strategic limitations of Hearthstone. This makes the game more fun, no doubt on that.

But the fact that something is good doesn’t mean that it’s beneficial regardless of the quantity. Water is good, yet too much can kill you.

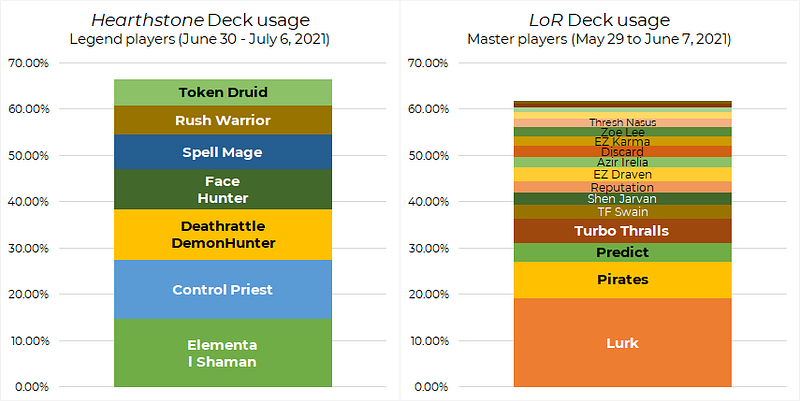

At the moment, LoR features +60 champions (most of which have their own unique victory strategy) and +35 advanced Keywords (out of the total 70). That is a huge amount, significantly higher than its competition.

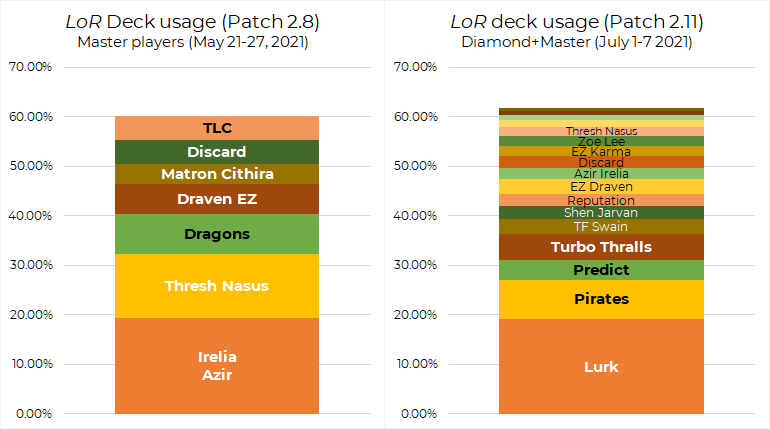

Hearthstone features only 5 classes, each with 2–3 major strategies (total 10–15). On the contrary, LoR has around 20 decks in the meta, just a tiny fraction of the total number of champions. It definitively has much more variety.

As we saw in our previous article, the current business strategy of LoR should focus on userbase growth. They need to increase their player count to be able to compete with older games.

This means keeping existing players engaged and reawaken churned users through new content and transforming newcomers into long-term players.

It’s a big entry barrier for new players

By having so many different mechanics from the beginning, LoR is quite overwhelming for any new player. The volume of content makes it not a good game to start with.

Especially if they’re fans of LoL, who don’t have an experience with CCG (they need to learn how to play a CCG and manage the huge range of LoR mechanics).

And yes, I know that this is not a problem in League of Legends, which throws you everything from the beginning. But just because it works there, it doesn’t mean it will here:

LoL has a huge component of your friends/team teach you how to play. This helps to go through the entry barrier. But in LoR, being a solo game, this doesn’t happen as naturally.

Although champions are unique, they fall into paradigms (tank, bruiser, jungle…) and roles that monopolize certain aspects of the game (jungle controls the jungle…).

Meaning that newbie players don’t have to deal with everything at once: The most common advice for starter players is to focus exclusively on a specific champion and role.Here, this is not possible because advanced decks can appear as opponents early on.

And finally, LoR is in a very crowded market space where others are the established products (contrary to LoL, where it is the standard). So it needs every little competitive advantage.

This means that early retention will be lower, adding more pressure on long-term retention.

To give a vision of how overwhelming the variety of game mechanics can be, LoR features 36 extended tutorials (!!!), named Challenges. But don’t get fooled by the name, they’re not challenge scenarios, they’re Keyword usage tutorials.

A couple of possible solutions to deal with this could be…

Limit the amount of mechanics on the game through a rotation system.

Add a mechanic, which progressively unlocks more mechanics as the player progresses.

Clash Royale does exactly that: As players progress through the arenas, they unlock cards. This allows keeping the game complexity to unfold progressively.

A lot of content doesn’t get to shine

But beyond the extra difficulty for new players, perhaps the biggest deal with the huge variety of strategies and mechanics is that most of them are wasted.

Players wouldn’t feel a big impact if several were to disappear tomorrow, they didn’t get to play with them, and they will make it harder to think on innovative ideas.

There are three reasons for that:

There are so many that some get no visibility. The number of deck archetypes in the game can be infinite, but the capacity to put them in front of the player’s eyes is limited.

This means that the player will realize only those in the spotlight (Thresh+Nasus, Irelia+Azir, Lurk…) but not others that are not widely used. Especially because, contrary to LoL, there’s no Champion selection screen that can help you realize their existence.

The design possibilities of every mechanic aren’t fully explored. This happens because many mechanics are exclusively used by one deck archetype.

For example, the main Lurk deck used in the current meta is Rek’Sai & Pyke, which interact with Lurk in a particular way (Rek’Sai guarantees the Lurk bonus, and Pyke increases the times it happens).

This means that the mechanic has been barely explored: What about a Countdown Landmark Lurk? Or a champion that lurks when challenging? Or a weak champion that can absorb the Lurk of others to raise its stats?This means that when Lurk is nerfed (the same as Blade Dance was), it would have represented only a fraction of the total depth it could’ve added to the game.

Many of them are not playable competitively. This decreases the actual amount of choices: There are many champions and deck archetypes to choose from, but in the end, only a few of them are truly viable.

In many cases, this is not because the strategy itself is less effective than the competitive ones in mechanical terms, but rather it’s a matter of tempo. Many of those black sheep mechanics could make it to competitive if they had an effective balance.

Although the latest 2.11 patch increased archetype variety in the meta (great job!!), considering that there are +60 champions, it still means that most of them are not used competitively (no Viktor, Jinx…). Source: Dr.Lor (runeterraccg.com) [2.8], [2.11]

We believe that this wasted potential of many mechanics makes PvE modes popular in LoR compared to other CCGs.

Game modes such as the Lab of Legends (PvE mode where the player progressively builds a deck based on a pre-set champion) are some of the few places that grant visibility and victory chances to several champions and decks.

Ultimately, we consider that many of those mechanics and champions could be used more efficiently, guaranteeing their moment in the spotlight of the meta with extra depth, and then moved to the game legacy.

#2: Limited deckbuilding

An arguable point here would be that the wide variety adds depth. Meaning that if it were removed, the game would lose the capacity to engage expert players.

Or, as the Game and UX designer Jeff Zhang said on his (fantastic) blog: “Everyonemight have an easier time keeping their head above water, but nobody really gets to swim.”

While I definitively agree with Zhang’s approach to game design on hardcore games, the problem is that nobody gets to really swim now, regardless of its variety of strategies.

Let me explain:

Limited emergent gameplay

Champion skills are generally very situational, often making sense only in the decks that have been specifically built to exploit them.

This is a smart decision, as it keeps emergent gameplay under control and makes much easier the creation of new champions and strategies and balancing them.

(Especially if we compare it with MTG, where it’s more likely that a crazy effect of one card will interact with another and generate unexpected synergies).

For example, Yasuo will only synergize with decks that make wide use of Stun, and Ashe with those that Frostbite. This limits the range of cards and champions that the skills will interact with in the same deck.

Unfortunately, it also means that the combos and strategies that you can carry out are limited to those that LoR designers placed there, rather than those that you — as the player — can discover.

Outside of the predicted combinations, cards don’t synergize enough to make unexpected or alternative combinations work.

Ultimately, we consider that this severely limits the capacity of expert players to find out alternative strategies to achieve victory or apply an already established strategy in an unorthodox way.

Jhonny players, which enjoy deckbuilding exploration, can’t play with unique decks that they craft. There are just too few synergic cards to achieve it. There are some imaginative decks, but they are those already pre-generated.

Few alternative deck builds

But perhaps there’s no need to go deep into the often dangerous waters of emergent gameplay:

The game could foster card exploration within the more under-control area by providing more depth and variation to the already established combinations.

Unfortunately, most of the content so far has focused on presenting a wide variety of deck strategies with unique gameplay each, but not on adding cards to allow multiple alternative ways to deliver a smaller range of strategies.

This means that players have little room for deckbuilding. There are very few alternatives to achieve the end goal or any given deck archetype or to counter a specific popular enemy strategy.

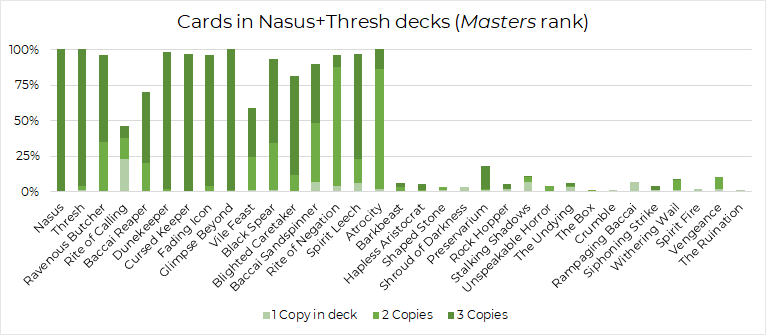

This translates into deck archetypes which are somewhat monolithic, where players tweak the amount of cards copies to improve drawing chances, but not the cards themselves:

In the graph: The archetype Nasus-Thresh has little variation of cards. Other than the main 16 cards (most of which have 2–3 copies in the deck), the rest are barely used. This means that there aren’t different viable versions of the same deck and that it has limited chances to be tunned for a specific matchup. Source: Dr. Lor (Mobalytics)

Consequences in progression: You either have the deck, or you don’t

The limited alternatives to each deck archetype have implications on the overall game progression (which we think it’s the actual big unresolved issue of LoR). There’s no poor man’s choice for a Nasus+Thresh deck.

This means that acquisition of a deck is boolean: Either the player the cards that compose deck to play, or she’s locked entirely from using that deck at all.

There’s no gradual acquisition of a deck, where the player has a suboptimal version, yet viable, and then progressively moves to its ultimate form.

We feel this may be one reason why the game is so generous with content. At the moment, they can only choose between giving you everything or locking you completely from playing some decks.

Our thoughts: Step by step

Ultimately, we consider that it would be a better approach to focus the game around a smaller set of key specific advanced strategies and mechanics (on top of the basic keywords like Elusive, Overwhelm, etc.).

Those mechanics would dominate the meta and affect a wide range of champions and territories. Several deck archetypes would use them, creating multiple ways to pursue the same strategies and more chances for synergies (although controlled).

Progressively, new mechanics and champions would be introduced by expansions.

The new archetypes would be balanced in a way that they counter the previously dominant strategies. The old mechanics would lose competitive effectiveness over time and eventually be rotated out.

The players that want to swim deep could go to a historic format and choose among the entire range of mechanics, where very likely balance would be less guaranteed (which is a design objective I consider impossible, given enough orthogonal growth).

This would guarantee that each keyword has its moment to shine and allow players to explore its design possibilities in-depth. At the same time, keeping complexity at bay for new players entering the meta and making it much easier to maintain balance.

And yes, this model is similar to MTG. But I don’t think this is not being original. I think this is taking the best practices of others and giving them a twist of improvement.

It is what Legends of Runeterra design have been doing all along.

Our Conclusions

We think that LoR has a very solid gameplay design.

Specifically, in terms of core mechanics (turn structure, mana, etc.), we consider it likely the top digital CCG because it gathers the best from the best while solving critical issues (accessibility in MTG and depth in Hearthstone).The game is definitively more deep than Hearthstone and less deep than MTG.

This last part is not bad since MTG may be too much to reach a mainstream audience and requires a huge creative effort to maintain (bigger team, more playtesting, more time between releases of new content…).We consider that, overall, the playable content is not at the same level of quality as the core mechanics and damages some of the best values of the core (player accessibility).

Not because it’s not good content (each piece of content is great).But instead, because its focus on a wide range of mechanics makes the game complex to enter but a bit shallow to master because each mechanic doesn’t have enough content to be explored in-depth.

This means that the gameplay has a strong entry barrier (harming early retention) and may lack some ability to keep experts interested for a long time (harming long-term retention).These problems may be solved through specific features (softening the range of mechanics in the early game) and managing the new content (especially if a rotation system is added).

Ultimately, we consider that gameplay is good enough, and not necessarily a point where Riot should be primarily focusing on changing their strategy.

In our humble opinion, the areas of the game that need work should be systems and in-game economy, as the game now has no progression and no collection mechanics due to — in part — being extremely generous.

This means that players have no long-term goals, lacking reasons to play for a long time.

In LoL, where a new champion means hundreds of hours of content until being mastered.

Once it has been completed, mastery over a specific deck is achieved much faster. So it can’t be something that keeps players hooked for as much time.We will deal with this last point more in-depth in our next article.

What’s next?

I hope you enjoyed this piece (congrats if you survived to this point!).

There’s only one article left about Legends of Runeterra, and it will be one with big bombs, as it will focus on dealing with the content management strategy:

We will review the different game modes and their purpose.

The issues it would face to introduce a rotation system (does it even need it?)

Review its monetization model (we may even go berserker and confront some of the statements of DoF on the topic of Riot’s monetization strategy).

And finally, we will explain why we think that their in-game economy is harming their long-term retention and how to solve it.

Hopefully, it won’t be as long as this one, which I think it’s the longest article I’ve ever written.

The next article may take a few weeks to come because this one was fun but exhausting.

Also — he said while shamelessly self-promoting — this month, July 2021, I’m in these two cool things:

The folks at ironSource just uploaded to their Youtube channel all the talks from their massive conference LevelUp 2021, organized together with Deconstructor of Fun. You can check here my talk on how to price items in F2P games.

And on the 19th, I’ll be at GDC 2021 (!!!) with a solo talk on how to diagnose, prevent and fix issues in F2P economies. If you’re attending GDC and want to learn more about how to manage free-to-play games, don’t miss out ^^ Link here

SPECIAL THANKS TO

As in the previous article, I would like to thank Ken Landen, Joseph Kim, Drew Levin, and Conrad McGee because our conversations about CCG were a big source of inspiration for my own thoughts.

Drew and Conrad specifically earn the medal of honor for taking the time to read an early version of the article and sending me feedback. You are truly amazing.

I would also like to thank Dr.Lor, vicioussyndicate.com, and hsreplay.net, for their fantastic data sources and analysis, which I used extensively to gather data.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author

You May Also Like