Using a 'lemon-shaped' structure to create the sanguine open-world of Sable

"We had to make a lot of things that weren't interdependent and could live without each other."

This interview has been edited for clarity

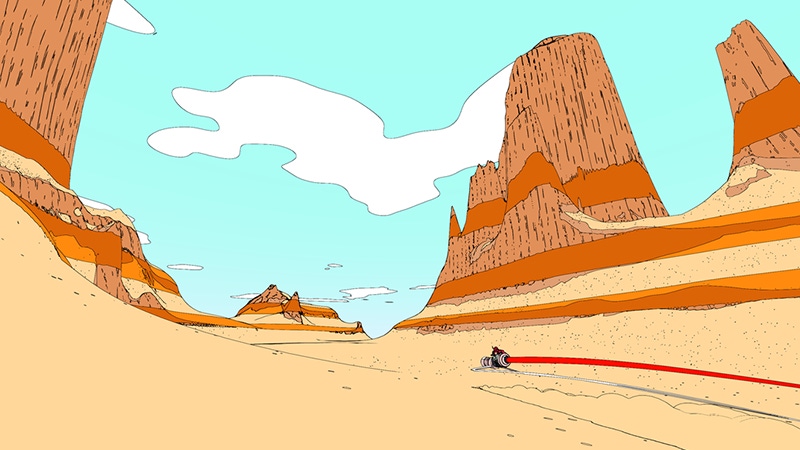

Sable, a wistful sojourn about self-discovery set among the sloping dune sea of a far away world, is that rarest of games. The ambitious project seemed to enchant players from the moment it was unveiled, with its Moebius-infused visuals and soothing soundtrack inviting would-be Gliders to dream about how their own adventure might unfold as they sail into the sapphire horizon.

After following the project for so long, it's hard to imagine Sable ever looking any different to the infinitely photogenic adventure that's been plastered across social media over the past few weeks. If you'd have clapped eyes on it in 2016, however, you'd have been treated to a vacant patch of desert and a bargain basement hovercar asset creative director Gregorios Kythreotis and technical director Daniel Fineberg swiped from an asset store for a paltry sum.

Speaking to Game Developer about the title's inception all of those years ago, the Shedworks co-founders explain that while the trappings might've been decidedly ramshackle back then, Sable's carefree soul had already flickered into existence.

"We just dumped this hovercar asset onto a bit of terrain and slapped some post-effects on it," Fineberg says, recalling how Sable looked after a few hours of tinkering. "It was just about driving that car, and then we put a big pyramid in the distance -- which was really just a big white cube -- and it became about seeing something cool on the horizon and this mantra of 'if you can see it, you can go there and explore it.'"

From there, Shedworks began fleshing out a playable prototype while mulling over how the title would incorporate other mechanics. At around the same time, Nintendo released a little game called The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, raising the bar for open-world adventuring and simultaneously giving Kythreotis and Fineberg the confidence to commit to creating their own nebulous take on exploration.

"We only started building the initial playable prototype in 2017, and that was when we started thinking about the gliding and climbing. At that point Breath of the Wild had just come out, and we were playing that and loved the mechanics," recalls Fineberg, noting that while Sable and Breath of the Wild aren't quite two of a kind, the latter project served as a proof of concept for their own bold foray into open-world development.

"We knew the structure that we wanted prior to that. We knew it was going to be this loose exploration game, and it was about finding things and learning from things [dotted around the world]. We called it a 'lemon shape,' because it had a beginning and end alongside a loose middle where the actual journey occurred," adds Kythreotis, who also praised the structure of freeform adventure A Short Hike for reassuring the team about the direction of their own project.

According to Fineburg, that initial playable concept was remarkably similar to the final product in a mechanical sense, and included climbing, gliding, and driving -- and, as is the case with the finished article, combat wasn't part of the equation. "[Avoiding combat] was a practical decision, but we also didn't really fancy doing that ourselves," he explains, joking about how hard it is to make a poor combat system, let alone one that shines. "It also wasn't really the story we wanted to tell."

As Sable started to scale up, Shedworks made a very deliberate decision to shun interdependent design. To help them cope with the pressures and challenges of open-world development, the team decided to focus on creating unique points of interest that housed morsels of what was effectively standalone content -- quests and tidbits that would flesh out the world if players dived into them, but weren't necessarily fundamental to the core experience.

Partially inspired by The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker's approach to world building, Kythreotis explains Shedworks made that decision early on to ensure they could chip away at the project without causing the whole thing to come tumbling down.

"The way we spoke about the [sand] dunes, for example, was that it's like a sea or ocean, and we had islands dotted throughout where content would live. What that structure allowed us to do was cut stuff that we didn't have time to finish or wasn't good enough without the rest of the game collapsing," he says. "That was something we knew we would do. We had to make a lot of things that weren't interdependent and could live without each other. That provides limitations in its own ways, but it was something we tried to embrace and make inherent to the structure."

It was a decision that demanded total commitment across that board, and required the studio to completely buy into whatever mechanical parameters had been set at the start of production.

"The height on the climbing we had a minimum amount, and everything was designed around that. There are only really a couple of places where the maximum amount is relevant. [...] You have to commit to a decision like that, because as a level designer you are making levels around that, so if you make changes you have to retroactively update all of your levels," Fineberg adds.

"There was one small problem with that. For example, the sprint came in really late. So there isn't anything designed around sprinting other than just getting around the world, but there's a jump early on in the tutorial section that players clearly can't make without the gliding stone. We eventually realized people had started trying that jump a lot, which wasn't really happening before we added the sprint."

Although the duo conceded there were some question marks around that approach, largely because of narrative limitations and concerns over player motivation, they also emphasized that the project simply wouldn't have been manageable had they taken another route.

"It was really important, and was ultimately what made this game viable. Because if we had a main quest where you had to hit three different locations, and then suddenly you can't make two of those locations, [...] then it's not just as simple as deleting a location. You have to start thinking about the ramifications," Kythreotis explains.

"I've seen instances where developers have planned their entire game, and they've blocked it out and it's 40 percent done. But then they have to finish it without cutting anything because it would fundamentally collapse the rest of the game. That was a pitfall we were aware of and didn't want to fall into. It affects everything. Every system. Every piece of workflow you have. Music, writing, design, programming, scripting -- everything is tied together if you do it that way."

Expanding on that point, Fineberg says that Sable was a leap into the unknown for the tiny studio. In many ways, their development journey echoes the journey of Sable herself, with Shedworks needing to feel their way into the vast expanse of open-world development without becoming overwhelmed by the sheer possibility of it all.

"We knew from the start we didn't know how long it would take to make one piece of content. How long would each location take to make? We didn't really know," says Fineberg. "So we decided to keep the structure loose enough that even if we only had the chance to make half, or even a quarter of the things we had planned, the structure of the game would remain intact. It needs to be elastic. It needs to be able to stretch around the content you have."

Kythreotis highlights that elasticity works both ways, and doesn't just mean you should fill your open-world with padding. Indeed, although Sable isn't exactly minute in scope, it presents a world that's deliberately sparse at times. In that sense, it can feel like the antithesis of many of its contemporaries, which often seem convinced players will lose interest if they aren't pelted with waypoints and quests from beginning to end.

For Shedworks, that wasn't just a trap worth avoiding, but one that was instrumental in realizing the truth of their serendipitous, soaring vision. "From a design perspective, [sometimes you need to have] more confidence in things being a bit smaller. I've brought it up a few times, but A Short Hike -- I'm just so jealous of that game. It's so clever and does a lot of the things we wanted to do," Kythreotis says. "Sometimes, if you're a bit insecure as a designer, you'll compensate by adding more -- but you might realize that you were better off making something smaller."

About the Author

You May Also Like