Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Sony's Kouno birthed adorable PSP title LocoRoco, and in this in-depth Gamasutra interview, he discusses its train-sketched genesis and his Short Circuit robot inspirations.

Designing games that truly suit the hardware platforms they're on is a more difficult proposition than it seems, at first blush - but Sony's Tsutomu Kouno has made a pretty good stab of it.

His history at the PlayStation-creating company includes work as a designer on the seminal Ico, but the first project he ever led was LocoRoco, the critically feted PSP 2D platformer which stars a pile of singing blobs.

While the game has perhaps not had as much commercial success as Sony and fans had hoped, it won the company a couple of BAFTAs, and more attention for its portable from a wide audience. The sequel, unsurprisingly called LocoRoco 2, was released in North America this month, after launching in Japan and Europe late last year.

In this in-depth Gamasutra interview, Kouno discusses the creative impetus which led to his creation of the LocoRoco characters, the core gameplay, and the wider cultural forces which helped inspire him. He also discusses his background and his thoughts about the wider industry.

I wanted to talk about developing a game for the PSP specifically, because it's a platform that has some different possibilities and different challenges than developing for a home console. When it comes to LocoRoco, the one thing you think about is the control, and I was wondering which came first: the game design or the control? From where did you proceed, when you originally thought of the first game in the series?

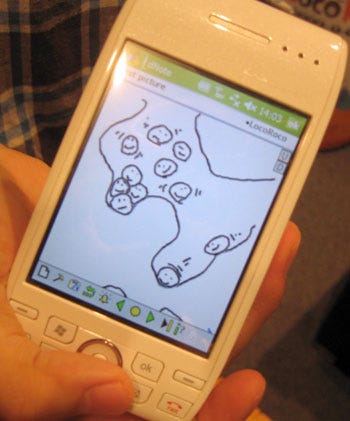

Tsutomu Kounou: When I came up with the concept for the first LocoRoco, I was spending a lot of time sketching game ideas while riding the train. These weren't just ideas for LocoRoco, there were a bunch I was working on. [Shows drawing]

So, this is the one that became the jumping off point for LocoRoco. When I looked at it, I saw that with so many characters on the screen, this wouldn't be the sort of game where you'd control a single guy directly.

So, this is the one that became the jumping off point for LocoRoco. When I looked at it, I saw that with so many characters on the screen, this wouldn't be the sort of game where you'd control a single guy directly.

But I also thought it might be cool if you could rotate the landscape around all of them. The picture's about the same dimensions of the PSP screen, and although it didn't have L and R buttons, but I'd tilt from side to side and think, "Hey, this might actually work."

After this initial drawing, I started churning out more sketches at a crazy pace. The PSP was also being released right around the time I first had these ideas, and using the L and R triggers to get the rotation seemed like an obvious choice.

When you saw the PSP's controls you decided the L and R buttons were the best control method for rotating the world.

TK: Well, I had the ideas in my head and drew these sketches right around the time the PSP came out. I thought it would make an interesting game, and knew that I'd want it to remain 2D, like the drawings. And when I thought of rotating the environment, clicking the L and R buttons just sort of came to me.

Did you prototype different control methods? Did you try different things before you arrived at the control for this game? Different button combinations, or something like that?

TK: I was pretty much set on using L and R from the start. Aside from those, we tried out a few different arrangements, but I realized quickly that I wanted the game to use as few buttons as possible, and we eventually pared it down to just one.

What was your thinking behind wanting to reduce the number of buttons? Was it wanting to make the game simpler for a wide audience, or to make it easy to play on the go as a portable?

TK: Yeah, I definitely wanted the game to be accessible to children. I also wanted it to be something people outside Japan could pick up and "get" without too much explanation, simply by pressing L and R.

Something I've been thinking about is that just because a game is simple, doesn't mean it can't be deep. Also, just because a game is complicated doesn't mean it is deep, necessarily. There's a balance you have to strike. Could you talk about making a simple game, but one that has depth to it?

TK: I think that's true. I wanted to start with a simple control scheme to bring as many people into contact with it as possible, including people who'd never played games before.

But when you dig into it, and say, try to clear everything in the game, you're really going to have to use your head. I wanted the game's appeal to work like that: something that draws you in initially, and then gets more interesting as you invest more time in it.

You made this game for the PSP, not the PS2. What changed in the way you thought about making the game when it came to making it for PSP rather than a home console where the user could sit and concentrate for a long time?

TK: When the PSP was first announced, it seemed to me like everyone was gearing up to make these complicated games for it, like sequels to games that had been on the PS2. I wanted to break that mold and make a game that really seemed at home on the PSP.

That had been my thinking ever since I heard about the portable. Coming up with the idea for LocoRoco right around the PSP launch was good timing, and I was lucky the control scheme worked so well.

It's like, if you don't make something new these days, gamers are likely to complain that your game is "just another sequel," or that it borrows from something else. I know I've often felt this way as a gamer, myself. So as a developer, I felt that pressure to make something new.

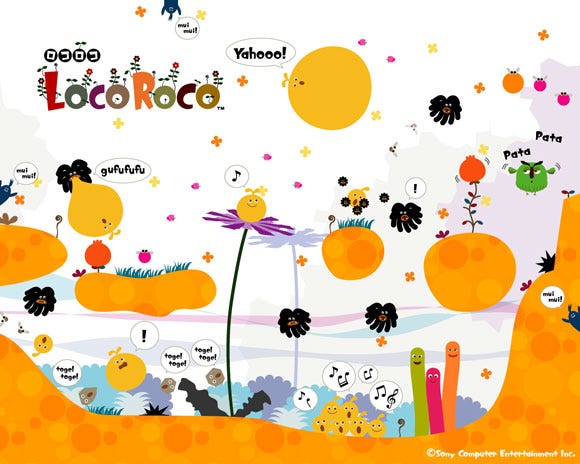

With LocoRoco, I wanted every aspect of the game, from the music to the first visual impression you get, to be unique. Polygons, complex character models, realistic shadows and lighting have become the standard for games today. I wanted to go the other way, and use a simple, effective 2D approach that would make even non-gamers say, "Hey, that's cute, I'd play that."

It's also common in games for the player to have direct control over their character, but this isn't the case in LocoRoco. The LocoRocos themselves often don't do what you want them to. It was sort of an experiment, looking back, but my hope was to create something that if done well, would introduce a new way to enjoy playing games.

Let me put it this way: It seems like most PSP developers try to replicate a PlayStation 2 game -- not necessarily a port or a copy, but the same style of game with 3D graphics. At some point, unless they think about it very carefully, the control fails to work right, or the game can't be played easily on the go. With that perspective in mind, I'm curious to see how the development proceeded to avoid those types of problems.

TK: Well, take the music, for example. I wanted to use music that you wouldn't normally expect to hear in a game -- music that reminded me of songs I was really into at the time.

But even with this, if you go with Japanese songs, foreign players can't understand the lyrics. I wanted the songs and their lyrics to contribute to the game's overall feel. We ended up creating a sort of LocoRoco "language" and used these made up words in the music to try and punch up the game's uniqueness.

As for the character design, we eventually ended up with this [points to promotional materials behind him], but originally we played around with a more claymation style of animation, and tried out all sorts of different textures, like fabric, for example.

We also had to stay within budget, though. So the challenge became, as a small team, how could we give the game the visual style we wanted, and keep costs down? We realized that if we made the LocoRocos like this [indicates final design], there'd be no need for fancy textures, and also that we could make them as big as we liked.

I knew that if we could nail down this aspect of the design, making the rest wouldn't be that difficult.

I also thought the graphics were really easy to see because of all the contrast. The characters are simple geometric shapes, they're easy to see. Is that another concern you had when designing the game visually?

TK: I actually didn't give all that much thought to visibility. (laughs)

Really?

TK: The goal was more to create a bright, cheerful game world. I did have one other reason for wanting to go with 2D graphics, though.

Complex 3D games were really the norm at the time, and we had this large character and wanted to keep the controls simple.

With 3D, you have to worry about things like getting the camera behind the character, or whether or not to give camera control to the player, and you wind up with a lot of superfluous controls.

Going 2D was my attempt to side-step all of that.

And this was mostly to appeal to the audience you were looking for, and to appeal to your own vision? Is that how you decided on these things?

TK: Well, this was the first game I'd been in charge of designing from start to finish. I mean, I've been tinkering around on PCs making little things since I was a kid, but this was the first game I'd designed as a product for sale.

One thing I've kept with me from childhood, though, is a desire to make something that would take the people of the world by surprise. I'd wanted to work for a game company ever since grade school, and it was around this time I first started making games in BASIC on the PC. I'd have my friends play them, and then ask what they thought.

What games inspired you at such a young age to want to become a game creator?

TK: There were a couple of Japanese games for the PC like Hydlide and Xanadu, as well as a text adventure game for Apple computers called Transylvania.

You know, the type of game where you enter a noun and a verb to say, "Do this with this." It had werewolves and all sorts of good stuff in it. At any rate, I had a lot of games. (laughs)

What was it about games as a medium that inspired you? What about games made you think they would be something you could use to surprise people?

TK: When I first had that impulse to create something that would take people by surprise, I wasn't thinking about games specifically. Ever since I was a kid, I've always loved inventing things, like making little robots and things. That movie from the 80s, Short Circuit, starred a robot, and it really made an impression on me.

That was one of my favorites when I was a kid, too.

TK: I heard each one of those robots cost about $160,000 to make. I actually ended up making a robot of my own, based on the one from Short Circuit. I brought it to school to show my friends, and people flipped out over it, which I thought was cool.

What's funny, is that the games you listed are relatively complicated games like RPGs or text adventures, but LocoRoco is so simple and easily understood, it lacks that hardcore sensibility. I just find it interesting, how you got from enjoying games like Xanadu to making a game like LocoRoco.

TK: Well, I've been a big fan of games since way back, but I also sort of kept an eye on the industry. From where I stood, it seemed like a lot of the games coming out were very similar to each other, and that didn't seem like a good thing to me.

Once I entered the industry myself, I felt like I had a responsibility to create something new. I remember feeling that really strongly: that I had to do something, anything, so long as it was different.

Before making LocoRoco, did you already work for Sony, or did you join the company right around that time?

TK: I actually got a job working with Sony right out of college. The first game I worked on was The Legend of Dragoon, an RPG for the PlayStation.

I was just a level designer at the time. After that, I was a level designer and planner for the game Ico.

After that, I had a stint as director for a Sony EyeToy game that was released in Europe as Monkey Mania. And finally after that, I was able to start work on LocoRoco.

It's interesting that the projects seem to get more simple as you went on. Legend of Dragoon is a very complicated game, like the Final Fantasy series. Ico is a similar game, but much less complicated.

Then EyeToy being less complicated still, and finally, LocoRoco. Is that just a coincidence? Or is it that as you started to learn what you could take away, and still be left with a good game?

TK: Actually, no. That's just been the direction the company's been heading in the last few years. But with all the projects I've worked on, I tried to bring as much of myself to my work as I could.

TK: Actually, no. That's just been the direction the company's been heading in the last few years. But with all the projects I've worked on, I tried to bring as much of myself to my work as I could.

For example, with Legend of Dragoon I was able to design the towns and their houses to my liking, and I installed a few slides in the game's castle. I also really like waterfalls, so when I worked on Ico I sprinkled a few of them here and there.

With the EyeToy game, I wanted to draw attention to the music, so I made sure the movement of the monkeys, even their expressions, coordinated with the sounds you heard.

There was also a game idea I'd had for a long time, a game that wasn't LocoRoco.

The concept of the game was to invigorate and cheer up anyone who played it, so I ended up borrowing a lot elements from this idea, and threw them in LocoRoco.

Moving on to the new LocoRoco game, what did you learn from the first game in terms of users and their reactions that you were able to apply to the next game in the series?

TK: Most of the feedback we got from players was really positive so we didn't want to mess with the original formula too much. But in answer to a few comments we heard, we made the level maps viewable in the second game.

We also wanted it to be easier for first-time players to beat the game with 100% completion, so we made it possible to see the location of the fruit you have to collect. We reduced the penalty for falling on spikes, things like that.

The first game was really well-liked by people. It did surprise them, I think as they weren't expecting it. How important is that user feedback to you in making the next game? You seem to be aiming to forge a connection with people via the game.

TK: Getting that feedback is incredibly important to me. For example, we did hear that some people found the first title too easy. So, for the second game, we added in some hidden areas with really difficult puzzles that even hard core users would have trouble solving.

That's one way we tried to respond to the player feedback we got. It's no easy thing though, pleasing all the people all the time. Like, if we get requests for things that go against the basic premise of the game we won't be able to include them.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like