The Fall of the 'Point-and-Click' Adventure Game

Has the internet age rendered the "point-and-click" adventure game hopelessly obsolete, or can gamers and developers work together to save a dying genre?

Background

The very first video game—if one is to be liberal with that classification—I ever played was the 1976 Colossal Cave Adventure, a DOS-based text-only adventure game in which the player explored a massive subterranean labyrinth and collected various items to further his progress by defeating foes or solving puzzles. The kernel of the game's design is, as is so often the case with great puzzle games, astoundingly simple: your goal is progress, you encounter obstacles, you collect items, you overcome obstacles by pairing the correct item with the appropriate action on the appropriate target. This simple structure yields an inherent depth, even when there are ultimately few items, actions, and things that may be acted upon. For example, to give a rough approximation, the number of possible combinations a player could potentially try with a full inventory would equal [(number of items) * (number of actions) * (number of things that could be acted upon)]. The result: a game with exceptional depth achieved based on a simple and attainable premise for the game designer.

Since the release of the Colossal Cave Adventure, countless games have evolved along substantially similar lines, eventually reaching the console market with NES games such as Shadowgate, Maniac Mansion, Deja Vu and Uninvited (together with a myriad of PC games). Thanks to the possibility of a GUI, a genre that in truth began in a text-based context ultimately adopted the moniker of the "point-and-click" adventure game. The genre reached its climax, one could argue, with the game Myst (and the subsequent series it spawned), where developers introduced a rich and engaging storyline; and increased the 'possible scenarios' to an extent that forced the player to abandon any realistic hope of success via a trial-and-error approach, electing instead to incorporate clues into the scenery and storyline which the player could use to guide his decision-making: a significant step forward for the genre.

These days, the true "point-and-click' adventure game seems to have all but disappeared. Admittedly, there are limitations inherent in the genre: there is virtually no replay value, for once you've figured out the sequence of what is to be done, the challenge disappears; and there is no social value in the genre, for telling a friend how something is accomplished undermines the principle challenge of the game, and trying to play any such game with a group is a recipe for frustration and boredom. That being said, there surely still exists a market demand for even the most rudimentary point-and-click adventure game that exceeds the supply (or lack thereof in this case) of new incarnations in the genre, and this discrepancy exists despite the relative ease with which a game of this ilk can be developed—a justification is called for.

The Underlying Nature of the Genre

The point-and-click adventure genre is a pointed representation of a theme ubiquitously present in all video games: increasing the difficulty-level of a challenge simultaneously and proportionately increases the player's level of frustration while trying to reach the goal (the Trial) and the player's level of elation at having overcome the challenge and reached the goal (the Payoff). Were it not the case that people in general find the joy of the Payoff to exceed the frustrations of the Trial, I daresay people might not play video games at all. By and large developers have scaled back the challenge level of all games over the years, perhaps in an effort to make games more accessible to those who are not so compelled to undertake a significant Trial, and are satisfied with the reduced Payoff of an easily-defeated game because they derive their game utility from other sources, such as social aspects or merely the passing of time. Yet the point-and-click adventure genre embodies a uniquely-fashioned difficulty-level profile that is difficult (if not impossible) for developers to foresee because it will vary significantly from player to player. This variable and highly volatile profile exists due to the ever-present possibility of 'getting stuck'—the circumstance in which the player's progress is stymied because he or she simply cannot figure out the next action required to allow further progress. As was mentioned previously, point-and-click adventure games have almost no replay value because once the player knows what to do, the challenge, and hence the essence, of the game is lost. This implies, however, that what makes a point-and-click adventure game enjoyable in the first place is the fact that what ought to be done next is not immediately obvious. Simple trial and error can be somewhat enjoyable, but it is those situations in which the player has to think long and hard about what ought to be done next—those Trials that eventually lead to a 'eureka!' moment—that give the genre its substance. It is those moments that push us towards the zenith of our frustration and angst, and yet it is those very same moments we eventually look back on with the most pride and satisfaction at having overcome.

The Conflict

It wasn't long after the dawning of the internet and information age that one could within days of a game's release hop online and find a comprehensive walkthrough of any adventure game. I've never been a fan of the walkthrough concept or similar manifestations such as strategy guides, etc.—to me this undermines the very concept of a game. But at least with respect to a game such as any in the Final Fantasy series a walkthrough destroys only the strategic elements for the player, leaving some degree of actual execution to provide a challenge—with respect to point-and-click adventure games, a walkthrough destroys everything that gives the game purpose and life. With a walkthrough in hand, the point-and-click adventure game devolves to the same state that is realized upon defeating the game: purposeless, without challenge, and a simple cause-and-effect chain that can be predicted with mathematical precision. A player beginning a point-and-click game with walkthrough in hand would be better served to save himself the time by declaring the game conquered before even loading it up.

At this point, the reader has surely devised a solution to the problem: simply don't use a walkthrough. Certainly this is an admirable mindset to embark with, but what happens when you truly get stuck? How long can you as a player hold out while knowing the solution is a few clicks away? Before the internet existed, players had little choice in the matter. Unless you wanted to admit defeat in the form of paying an outrageous charge to call the NES hotline, you were stuck wandering around the castle Shadowgate clicking on every little thing and reexamining every room until finally the correct action was taken. As has been mentioned, these are the moments that define the quality and nature of the genre. Overcoming frustration through personal perseverance is part of what makes games as a whole great, but a person's willpower in those moments of frustration will be severely tested if he knows he can end the frustration with great ease. If a man sets out into the woods and resolves to survive by making a fire with sticks and leaves, how long will he bear the frustration of failure, the physical toll on his body, the hunger and the cold if he has a lighter in his pocket? Willpower will only take one so far—the outdoor adventurer may abandon his cell phone and lighter to divest himself of temptations in order to achieve his true personal goal, but the gaming adventurer cannot truly divest himself of the internet.

The scope of this problem, unfortunately, runs even deeper than a matter of willpower. Suppose the existence of a player with perfect willpower who has resolved to defeat a point-and-click adventure game without an ounce of outside help of any kind—even if he gets stuck for months on end trying to figure out the next correct move—and who is so resolute that he will indeed never give in to temptation. If playing an old game, like 1987's Shadowgate, such a player knows definitively that he can defeat the game without outside help, for the game was designed at a time when outside help was generally not available and so part of the development of the game certainly involved ensuring that a player could defeat the game on his own. But now, developers are aware that players will have access to online walkthroughs, the so there exists the possibility that a developer will incorporate into his point-and-click adventure game an obstacle that actually requires the player to seek the solution on the internet or in a strategy guide (that is to say, the solution is made so obscure it goes beyond the realm of what a player could reasonably be asked to figure out on his own). Our ideally-resolute gamer playing Shadowgate can, in times of great frustration, always remind himself that the solution to any obstacle is indeed there to be found and can reasonably be ascertained with some pluck and perseverance; our ideally-resolute gamer playing a modern point-and-click adventure game, however, will always have the nagging and entirely realistic suspicion in the back of his mind any time he gets stuck that the solution may actually lie beyond that which is contained within the game itself, viz., it may turn out to be the case that he has embarked on a hopeless campaign to figure out something which simply could not by any reasonable person be ascertained. Not even the ideally-resolute gamer can resist temptation for too long once this possibility is in play; and it is only after the spoiler has spoiled that the player will know if the impediment was something he could have and should have been able to himself overcome, or if the solution was beyond the pale of what could reasonably be asked of his problem-solving faculties.

Conclusion

Since the invention of the turbo controller for the SNES I have considered the need for a code of ethics to be established in the gaming world. While I at this point have not given the matter nearly enough thought to propose much in the way of specifics, I might offer that the basic underlying idea would be the establishment of something of a guild binding both players and developers by honor to certain standards and understandings. In the case of the point-and-click adventure game, developers would affirmatively attest that, however difficult the game may be, everything in the game could be reasonably ascertained and the game defeated without assistance from any outside sources; and gamers would in turn agree to seek no outside assistance in completing the game, no matter how perplexed or frustrated they may become. Obviously this code would require significant development and variation from the basic framework I have just now laid out, but the reader should be able to grasp the underlying premise behind the idea, even in its infancy. Without the development of such a code, I see no way that the point-and-click genre can persist in a meaningful capacity—developers will try to increase the difficulty in the only way they can in light of the existence of the internet: by creating content that virtually requires the player to seek assistance outside of the game itself; and gamers will give in to temptation and find solutions online whenever frustrated beyond the threshold of their willpower. It would truly be a shame to lose the point-and-click adventure genre—I'm sure many look back on their gaming accomplishments and place defeating Myst quite high up on the list. Because every point-and-click adventure game yields its own sequence and its own story, it is nearly impossible for the genre to get old as long as you have good story-tellers and puzzle-constructors creating games, and I believe there is yet a wealth of excellent games that could be developed in this genre that would provide immense satisfaction to those gamers willing to dedicate themselves to a truly difficult and trying endeavor.

Background

The very first video game—if one is to be liberal with that classification—I ever played was the 1976 Colossal Cave Adventure, a DOS-based text-only adventure game in which the player explored a massive subterranean labyrinth and collected various items to further his progress by defeating foes or solving puzzles. The kernel of the game's design is, as is so often the case with great puzzle games, astoundingly simple: your goal is progress, you encounter obstacles, you collect items, you overcome obstacles by pairing the correct item with the appropriate action on the appropriate target. This simple structure yields an inherent depth, even when there are ultimately few items, actions, and things that may be acted upon. For example, to give a rough approximation, the number of possible combinations a player could potentially try with a full inventory would equal [(number of items) * (number of actions) * (number of things that could be acted upon)]. The result: a game with exceptional depth achieved based on a simple and attainable premise for the game designer.

Since the release of the Colossal Cave Adventure, countless games have evolved along substantially similar lines, eventually reaching the console market with NES games such as Shadowgate, Maniac Mansion, Deja Vu and Uninvited (together with a myriad of PC games). Thanks to the possibility of a GUI, a genre that in truth began in a text-based context ultimately adopted the moniker of the "point-and-click" adventure game. The genre reached its climax, one could argue, with the game Myst (and the subsequent series it spawned), where developers introduced a rich and engaging storyline; and increased the 'possible scenarios' to an extent that forced the player to abandon any realistic hope of success via a trial-and-error approach, electing instead to incorporate clues into the scenery and storyline which the player could use to guide his decision-making: a significant step forward for the genre.

These days, the true "point-and-click' adventure game seems to have all but disappeared. Admittedly, there are limitations inherent in the genre: there is virtually no replay value, for once you've figured out the sequence of what is to be done, the challenge disappears; and there is no social value in the genre, for telling a friend how something is accomplished undermines the principle challenge of the game, and trying to play any such game with a group is a recipe for frustration and boredom. That being said, there surely still exists a market demand for even the most rudimentary point-and-click adventure game that exceeds the supply (or lack thereof in this case) of new incarnations in the genre, and this discrepancy exists despite the relative ease with which a game of this ilk can be developed—a justification is called for.

The Underlying Nature of the Genre

The point-and-click adventure genre is a pointed representation of a theme ubiquitously present in all video games: increasing the difficulty-level of a challenge simultaneously and proportionately increases the player's level of frustration while trying to reach the goal (the Trial) and the player's level of elation at having overcome the challenge and reached the goal (the Payoff). Were it not the case that people in general find the joy of the Payoff to exceed the frustrations of the Trial, I daresay people might not play video games at all. By and large developers have scaled back the challenge level of all games over the years, perhaps in an effort to make games more accessible to those who are not so compelled to undertake a significant Trial, and are satisfied with the reduced Payoff of an easily-defeated game because they derive their game utility from other sources, such as social aspects or merely the passing of time. Yet the point-and-click adventure genre embodies a uniquely-fashioned difficulty-level profile that is difficult (if not impossible) for developers to foresee because it will vary significantly from player to player. This variable and highly volatile profile exists due to the ever-present possibility of 'getting stuck'—the circumstance in which the player's progress is stymied because he or she simply cannot figure out the next action required to allow further progress. As was mentioned previously, point-and-click[M1] adventure games have almost no replay value because once the player knows what to do, the challenge, and hence the essence, of the game is lost. This implies, however, that what makes a point-and-click adventure game enjoyable in the first place is the fact that what ought to be done next is not immediately obvious. Simple trial and error can be somewhat enjoyable, but it is those situations in which the player has to think long and hard about what ought to be done next—those Trials that eventually lead to a 'eureka!' moment—that give the genre its substance. It is those moments that push us towards the zenith of our frustration and angst, and yet it is those very same moments we eventually look back on with the most pride and satisfaction at having overcome.

The Conflict

It wasn't long after the dawning of the internet and information age that one could within days of a game's release hop online and find a comprehensive walkthrough of any adventure game. I've never been a fan of the walkthrough concept or similar manifestations such as strategy guides, etc.—to me this undermines the very concept of a game. But at least with respect to a game such as any in the Final Fantasy series a walkthrough destroys only the strategic elements for the player, leaving some degree of actual execution to provide a challenge—with respect to point-and-click adventure games, a walkthrough destroys everything that gives the game purpose and life. With a walkthrough in hand, the point-and-click adventure game devolves to the same state that is realized upon defeating the game: purposeless, without challenge, and a simple cause-and-effect chain that can be predicted with mathematical precision. A player beginning a point-and-click game with walkthrough in hand would be better served to save himself the time by declaring the game conquered before even loading it up.

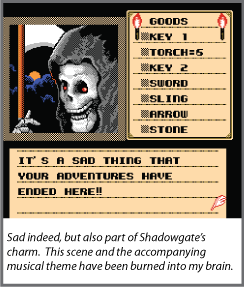

At this point, the reader has surely devised a solution to the problem: simply don't use a walkthrough. Certainly this is an admirable mindset to embark with, but what happens when you truly get stuck? How long can you as a player hold out while knowing the solution is a few clicks away? Before the internet existed, players had little choice in the matter. Unless you wanted to admit defeat in the form of paying an outrageous charge to call the NES hotline, you were stuck wandering around the castle Shadowgate clicking on every little thing and reexamining every room until finally the correct action was taken. As has been mentioned, these are the moments that define the quality and nature of the genre. Overcoming frustration through personal perseverance is part of what makes games as a whole great, but a person's willpower in those moments of frustration will be severely tested if he knows he can end the frustration with great ease. If a man sets out into the woods and resolves to survive by making a fire with sticks and leaves, how long will he bear the frustration of failure, the physical toll on his body, the hunger and the cold if he has a lighter in his pocket? Willpower will only take one so far—the outdoor adventurer may abandon his cell phone and lighter to divest himself of temptations in order to achieve his true personal goal, but the gaming adventurer cannot truly divest himself of the internet.

The scope of this problem, unfortunately, runs even deeper than a matter of willpower. Suppose the existence of a player with perfect willpower who has resolved to defeat a point-and-click adventure game without an ounce of outside help of any kind—even if he gets stuck for months on end trying to figure out the next correct move—and who is so resolute that he will indeed never give in to temptation. If playing an old game, like 1987's Shadowgate, such a player knows definitively that he can defeat the game without outside help, for the game was designed at a time when outside help was generally not available and so part of the development of the game certainly involved ensuring that a player could defeat the game on his own. But now, developersare aware that players will have access to online walkthroughs, the so there exists the possibility that a developer will incorporate into his point-and-click adventure game an obstacle that actually requires the player to seek the solution on the internet or in a strategy guide (that is to say, the solution is made so obscure it goes beyond the realm of what a player could reasonably be asked to figure out on his own). Our ideally-resolute gamer playing Shadowgate can, in times of great frustration, always remind himself that the solution to any obstacle is indeed there to be found and can reasonably be ascertained with some pluck and perseverance; our ideally-resolute gamer playing a modern point-and-click adventure game, however, will always have the nagging and entirely realistic suspicion in the back of his mind any time he gets stuck that the solution may actually lie beyond that which is contained within the game itself, viz., it may turn out to be the case that he has embarked on a hopeless campaign to figure out something which simply could not by any reasonable person be ascertained. Not even the ideally-resolute gamer can resist temptation for too long once this possibility is in play; and it is only after the spoiler has spoiled that the player will know if the impediment was something he could have and should have been able to himself overcome, or if the solution was beyond the pale of what could reasonably be asked of his problem-solving faculties.

Conclusion

Since the invention of the turbo controller for the SNES I have considered the need for a code of ethics to be established in the gaming world. While I at this point have not given the matter nearly enough thought to propose much in the way of specifics, I might offer that the basic underlying idea would be the establishment of something of a guild binding both players and developers by honor to certain standards and understandings. In the case of the point-and-click adventure game, developers would affirmatively attest that, however difficult the game may be, everything in the game could be reasonably ascertained and the game defeated without assistance from any outside sources; and gamers would in turn agree to seek no outside assistance in completing the game, no matter how perplexed or frustrated they may become. Obviously this code would require significant development and variation from the basic framework I have just now laid out, but the reader should be able to grasp the underlying premise behind the idea, even in its infancy. Without the development of such a code, I see no way that the point-and-click genre can persist in a meaningful capacity—developers will try to increase the difficulty in the only way they can in light of the existence of the internet: by creating content that virtually requires the player to seek assistance outside of the game itself; and gamers will give in to temptation and find solutions online whenever frustrated beyond the threshold of their willpower. It would truly be a shame to lose the point-and-click adventure genre—I'm sure many look back on their gaming accomplishments and place defeating Myst quite high up on the list. Because every point-and-click adventure game yields its own sequence and its own story, it is nearly impossible for the genre to get old as long as you have good story-tellers and puzzle-constructors creating games, and I believe there is yet a wealth of excellent games that could be developed in this genre that would provide immense satisfaction to those gamers willing to dedicate themselves to a truly difficult and trying endeavor.

[M1]dump quotes on all but first

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)