Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How can you measure player reaction to games? From Half-Life 2 through Gears Of War, this Gamasutra article compares engagement levels via brain, heartrate, and temperature checks.

[How can you measure player reaction to games? Using games from Half-Life 2 through Gears Of War, this Gamasutra article, originally published in Game Developer magazine, shows how tech company Emsense uses brainwaves, heart activity, and even blinking to estimate engagement.]

By 2007, the next-gen ecosystem had come of age. The Xbox 360 had been out for more than a year, and both the PlayStation 3 and Nintendo's Wii had hit the market with a slew of new titles. The shooter genre, in particular, had pushed the envelope both in terms of graphics as well as new gameplay.

As part of our research activities at EmSense, a San Francisco-based company that uses proprietary brain monitoring EEG and bio-sensing technology to measure engagement and emotional and cognitive responses to content, we set out to understand exactly what defined the successful modern, next-gen shooter title.

Where does it engage, and where doesn't it? How do players actually respond to new innovative gameplay (minus the hype)? We were also determined to identify broad trends that have occurred across all next-gen titles.

We started by looking at how players responded to then-new first- and third-person shooter video games on the market: Battlefield 2142, Call of Duty 3, F.E.A.R., Gears of War, Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter 2, and Resistance: Fall of Man. We added two "classics," Halo 2 and Half-Life 2, to provide perspective from the previous generation of titles.

We measured players' responses to the first 90 minutes of those games, a time that we consider the most important for making a positive impression.

More than 300 hours of physiological and gameplay data were generated and analyzed to develop our findings.

We came in with no preconceptions, no prejudices, and let the response data demonstrate what worked and what didn't. The results are at times a confirmation of existing techniques that are timeless to good game design, and at other times, surprising and revealing about what gamers truly care about but often can't find a way to say.

1. Cutscenes with overarching emotional themes.

Uncovering the "perfect" cutscene, in terms of power of physiological emotional response, proved to have no formula. Just like their cinematic movie counterparts, game cutscenes have no single creative blueprint. As you can imagine, a horror film evokes a different set of emotions than a comedy, but both may be powerful and effective pieces of art.

What we did find is that games like Gears of War, F.E.A.R., and Call of Duty 3 consistently engage players by specializing in a particular thematic emotion.

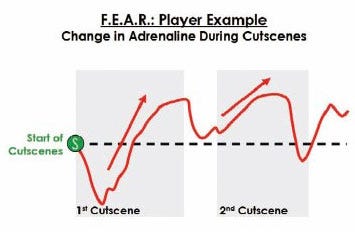

In F.E.A.R., for example, dark themes and creepy music consistently translated to a high level of engagement. The introductory cut scene of F.E.A.R. was associated with a high level of adrenaline, even more so than much of the combat in the game. Creative elements like dialog, music, and blood-filled scenes combined to create this strong fear response about 73 percent of the time -- significantly higher than the genre average we recorded for cutscenes.

Call of Duty 3 used a different formula, albeit one that is just as effective. Its most engaging cutscenes came not from fear, but from a feeling of reward, as measured by our positive emotion vector. Each of the cutscenes at the end of a level in Call of Duty 3, which naturally included NPC encouragement for a job well done, led to a strong positive reward response in up to 80 percent of players. It was a simple and effective way to link the intensity of gameplay with feelings of accomplishment.

Our big surprise came with Gears of War. We examined the 10 biggest events in Gears of War as defined by the highest levels of recorded player engagement. We weren't surprised when we saw fights against swarming Wretches or other epic battles. What we didn't expect to see was a cutscene: Lieutenant Kim, the protagonist's comrade, is killed suddenly and violently by enemy forces.

Together, over 80 percent of players reacted with one of the 10 most intense engagement responses of the game, no small feat for a title with bloody chainsaws and huge courtyard battles. Consistently, Gears of War players showed high levels of engagement during action, battle sequences, and when in conversation with their comrades.

2. Tutorials integrated into combat.

As games (and controllers) become more and more complex, teaching players the mechanics of the game has become one of the big challenges for developers in general.

All our research indicates that male game players in the 18 to 34 year-old demographic are not receptive to being told what to do -- and they learn most effectively by doing.

We've seen two side effects that reinforce the importance of having engaging tutorials. First, and most obviously, players who don't know how to play the game consistently have lower recorded engagement levels throughout their play session, as they continue to struggle to immerse themselves in gameplay, even after the introductory tutorials and levels have finished.

Second, long and boring tutorials delay the first moment of engagement, that critical moment when players realize they can indeed be immersed in this game. In some games we've tested, the first strongly engaging event does not occur until 20 minutes into the experience, a lifetime for a gamer who just wants to have fun.

The most important takeaway for developers regarding this finding is to not leave the creation of tutorials until the end of the production cycle. Tutorials can (and moving forward into future generations of hardware, will) be the first moment of true engagement in the game.

Two games that add new gameplay in this test sample were Gears of War and Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter 2. The former adds a cover mechanic. Ghost Recon has a cross-com remote camera heads-up display, squad-based combat, smoke grenades, unmanned aerial vehicles -- the list goes on and on.

These games engaged users quickly with a simple strategy. Players were thrown into action and were threatened, and were expected to learn. The player learns to throw grenades not by tossing one into a dummy box target, but by utilizing them against enemies with real consequences on the line.

Gears of War not only forces players to learn gameplay mechanics under fire, but it gives them the option of skipping the tutorial altogether and being thrown directly into battle. Forty percent of subjects in our study did in fact skip the tutorial, but regardless of whether they did this, they engaged with the game strongly and quickly. In fact, average engagement during the first level was comparable to that in subsequent levels.

The entire first level of Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter 2 is a tutorial, a "simulation" that nonetheless has failure conditions and appears indistinguishable from standard combat. An emotional and adrenaline climax occurs when players utilize smoke grenades and explosive charges to take out a heavily outfitted, armored personnel carrier.

In fact, the alternation between the calm of instruction and the intensity of trying new tactics against powerful enemies created a big emotional roller coaster that registered as one of the top two most engaging events out of the eight titles we studied.

3. Bring players down to bring them back up.

The roller coaster analogy is an apt one to describe players' engagement and physiological responses. The fun lies in going up and down on the ride. Staying at the same elevation is about as much fun as riding a monorail. Creating emotional drama, of course, is easier said than done in video games.

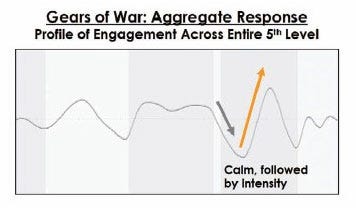

It seems counterintuitive, but the most intense points of engagement in the titles in our study were often the result of calm moments. Downtime, a period of lower engagement, is not always bad. Periodic but brief lulls in action allow for more intense action sequences and stronger reactions to climactic final battles. The emphasis is on "brief"; take too long, and players are truly disengaged and want (to continue the analogy) to get off the ride.

The most important thing for developers to understand is that the two elements -- big intense events and brief lulls -- must both occur. One doesn't function without the other.

Examples of big, high-intensity moments included epic courtyard battles (Call of Duty 3, Resistance, Gears of War), powerful enemy bosses (Ghost Recon, Gears of War), and swarms of small ones (Half-Life 2, Resistance, and Gears of War).

Creating the calm before the storm is much trickier. We identified a few strategies. In Gears of War, there's a surprising amount of walking around, listening to the radio com -- and these moments explicitly calm players just before hordes of Locusts appear from their emergence holes.

Half-Life 2 used a different method. In between combat, puzzles provided an emotional break from action. As expected, these puzzles did not evoke adrenaline, but they did elicit engagement and more specifically, positive emotion in droves. Engagement was 17 percent higher than the benchmark, and the recorded level of positive emotion upon completion (the "reward" feeling of finishing) was additionally nearly 20 percent higher than the norm. It is Half-Life 2's back and forth between the adrenaline of combat and the reward of puzzles that creates its roller coaster.

4. Close combat, close combat, close combat.

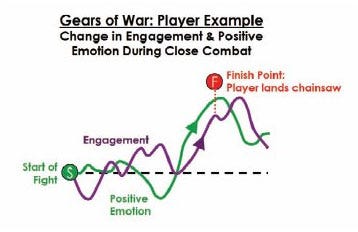

Close combat was the most reliable method of creating engagement, adrenaline, reward, and all the emotions that make shooters so much fun. Certainly, this is nothing new to the genre, but the next-gen games that excelled in this area were exceptionally strong at creating high-paced close combat frequently.

It was no surprise to us that the three games in this study widely considered "game of the year" (Gears of War, Halo 2, and Half-Life 2) all designed and executed exceptional melee weapons to encourage or force close combat.

The most successful FPS titles encourage close combat, dangling emotions of reward to compel players into high-risk, adrenaline-pumping scenarios that dramatically increased their level of engagement and feelings of reward.

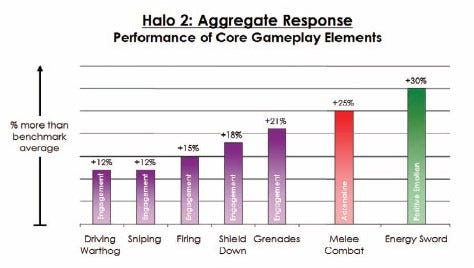

For instance, in both Halo 2 and Gears of War, players were rewarded with an instant kill for using the energy sword and chainsaw. An energy sword kill in Halo 2, for instance, evoked 30 percent more recorded positive emotion and reward than the genre benchmark.

In addition, Gears of War players recorded high emotional reward for the spray of enemy blood after they succeeded. Of course, we can't forget the ubiquitous Half-Life 2 crowbar, the only weapon players initially have for fighting.

Other games don't only encourage close combat -- they force it. In Ghost Recon, we've already mentioned how players are instructed to destroy an armored vehicle in the only way possible: planting a charge in close proximity to the vehicle. In Call of Duty 3, players are thrown into a close-quarters mini-game struggle with a German soldier. Both events led to high measures of engagement, but these events occurred once or twice in a session, unlike the dozens and dozens of exhilarating moments found in the games that distinguished themselves.

It's not just the melee weapon itself that encourages close combat. Just listen to battles in Gears of War. Amidst the cacophony of bullets, players can hear their teammates tell them to flank the enemy. What the comrades forget to say is that narrow firefight areas and emergence holes can immediately make these flanking expeditions devolve into melee combat. Consistently, we measured increased engagement and intensity to these episodes.

The takeaway for developers is that creating next-gen experiences is about exhilaration. Nowhere did these shooters distinguish themselves more than in the ability to consistently throw gamers into close combat.

5. Little things make a big difference.

Games with proven multiplayer popularity were fast-paced with consistently engaging core elements. These elements, like melee weapons, vehicles, and grenades, easily translated from a single player experience to multiplayer.

A look at our pacing metrics -- measuring how frequently players respond to gameplay events physiologically -- reveals a familiar top two for fastest pacing: Gears of War (pacing was 51 percent above the average) and Halo 2 (35 percent above average).

Our system utilizes time-coded tags when a key event occurs (for example, when a Halo 2 player's shield drops) and correlates it with the corresponding emotional data. Many titles have a standout feature that always engages, but for games like Halo 2 and Gears of War, every little element of gameplay engages. In Halo 2, "shield down" correlates with an engagement response 18 percent above average, and grenades show engagement at 21 percent above average. These supposedly little elements add up simply because they occur so often in a play session.

The result is an inherently fun gameplay experience that doesn't rely on big scripted events to create engagement. However, there's also a huge cursory benefit. All these engagement systems translate easily and directly into multiplayer gameplay. All Gears of War and Halo 2 need to do to give players a fun time is throw them into a deathmatch and watch the mayhem.

1. Cutscenes that inform, rather than entertain.

Cutscenes open up a big opportunity for creating a cinematic experience. Games like Call of Duty 3, F.E.A.R., and Gears of War leverage them successfully to stimulate emotion in players.

However, other titles in this study struggled with maintaining engagement during cutscenes more than any other element. Players say they want them, but cutscenes in general are not as engaging as combat or other interactive gameplay. All too often, cutscenes simply served as the cursory bridge between two levels.

Underperforming cutscenes showed a distinct pattern. Most were highly informational and involved "talking heads" or narration. Briefing-style cutscenes often fall into this category. For instance, Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter 2 evoked an incoherent response during cutscenes across players. Its scripted briefings did not consistently engage players. Players did not even strongly think about the information in the briefings, a clear sign that these cutscenes were not grabbing players' attentions.

In Resistance, engagement dropped significantly in 57 percent of cases during cinematics. Cutscenes here recount the Chimeran attack and Nathan Hale's journey, leading to long sections of emotional disengagement. Dynamic scenes of action and conversation between characters, on the other hand, demonstrated a stronger ability to engage and influence emotions.

Even extremely high-performing games suffer from disengaging cut scenes. Halo 2's cutscenes disengaged players 64 percent of the time, in stark contrast to its extremely engaging core gameplay. Results like this confirm that Halo 2 single player is fun more for the joy of combat than any cut scene or storyline element. It also suggests that, given the tight timeframes inherent in every production schedule, knowing how to allocate production efforts is as important as game design itself.

The proper use of cutscenes is certainly one area we feel has broad applicability across genres, particularly as next-gen, triple-A titles are increasingly expected to deliver big cinematic experiences. Indeed, it raises questions about the role of cutscenes: to inform or entertain.

Predictably, Gears of War seems to get it right. Its cutscenes are filled with action, while information is largely communicated via radio and conversations during lulls in gameplay, in between firefights. Our data demonstrates that entertaining cutscenes engage and connect with players at the emotional level.

2. Boot camps and training areas.

We've all seen the classic boot camp in war movies, televisions shows, and video games. Pushed on by staff sergeants, recruits are put through the paces and come out stronger and ready to fight.

There's only one problem: The act of learning to shoot a gun, throw grenades, and perform hand-to-hand combat against dummy targets isn't very engaging. In the critical first minutes of the game, when players' first impressions are made, tutorials isolated from the action and storyline leave players emotionally disengaged.

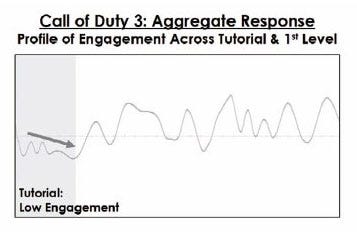

Nowhere was this more apparent than in Call of Duty 3. Its training area, where players are taught how to fight without danger or penalty for failure, led to below-average emotional engagement for the first seven minutes of gameplay -- that's seven long minutes when players are not immersed and not entertained. Only when players were thrust into battle did engagement rise again.

Through our years of testing and analyzing video games, we've found very few absolute rules in game design, but this one seems to come close. Titles that do not make its tutorials a "game," with their own sets of rewards and failure conditions, are not as engaging as those that do.

3. Broken roller coasters.

There's only so much intensity players can handle. Games that try to keep intensity continuously high created (counter-intuitively) an experience that was actually less intense, less cinematic, and less "epic."

This problem occurred in two ways. First, games that do not vary the intensity of events ultimately began to lose players. Over time, we measured what amounted to attenuation. These games actually led to smaller and smaller responses to each repetitive event. Halo 2 excelled in fast-paced action, but one side effect was a single player experience that was less intense. In the first level of Halo 2, players only faced a mix of smaller threats. As a result, the intensity of that level was up to 40 percent lower than in other games.

Second, level designs that begin with an intense firefight may have captured players' attention, but often they overshadow subsequent events. Players' engagement across the rest of the level, by comparison, was significantly lower in these circumstances. It amounts to an emotional letdown.

For example, the second level of Call of Duty 3 starts with an extremely intense battle, but players' emotional engagement for the rest of the level was comparably lower. This was not the climactic finish that we've heard so many developers want to try to shoot for.

4. Repetition and assured outcomes.

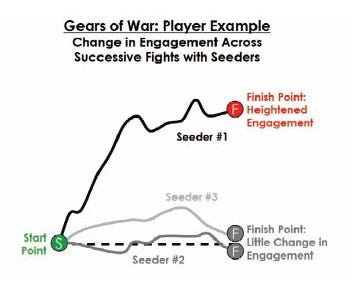

We also discovered how important novelty and its close cousin, the unknown, are to engaging players. The Seeder in Gears of War provides a nice case study of this phenomenon. In the first 90 minutes of gameplay, players encounter three Seeders, one at a time. Killing them can only be done with the Hammer of Dawn weapon, and taking them down is crucial to restoring radio communications.

The result is that the novelty of the first encounter with this enemy makes the gameplay intensely engaging. However, the second and third encounters with Seeders do not engage players at nearly the same level of intensity. In some sense, emotion data demonstrated that players only went through the motions with the second and third Seeders.

Do exceptions exist? Sure they do, even in the same game. The wretches in Gears of War, fast-moving, crawling, and with swarms of Locust enemies, consistently engaged players in part because players were often pinned to the only thing that could save them, a Troika machine gun turret.

We think the important distinction here is not repetition, but the unknown outcome. Once players locked onto the Seeder with the Hammer of Dawn, it was fairly clear that it was going down pretty quickly. However, for each wave of Wretches, the player had no idea if he would be able to fight them off in time.

5. Gameplay innovation through novel weapons.

Results demonstrate that novel weapons can have a huge payout, but also a big downside if not executed well.

First, a definition: "Novel weapons" is a term we use for unique and powerful weapons beyond the standard pistol and machine gun. This includes high-powered sniper rifles, machine gun turrets, battle walkers, tanks, and other vehicles.

Introducing these differentiating gameplay elements has increasingly become a focus of innovation (and risk) to game developers and marketers.

What separates the engaging from the disengaging -- and why these weapons are such double-edged swords -- is a consequence of their power. When players are protected and not getting harmed, utilizing these weapons led to low engagement levels. When players were consistently damaged, unprotected, or challenged by equally powerful enemies, the payoff was huge: engagement rose often to off-the-charts levels.

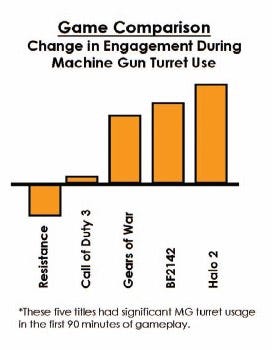

We looked at two high-powered weapons, sniper rifles and machine gun turrets, two frequently implemented elements in most shooters. Machine gun turrets, on average, have long been superior engagement performers in our database of elements.

However, some games, including some in this test group, continued to fail to engage, leading to huge missed opportunities. For instance, engagement to Resistance's machine gun turrets was a full 19 percent below leader Halo 2. That's the difference between an exciting experience and one that, frankly, is a disappointment.

However, some games, including some in this test group, continued to fail to engage, leading to huge missed opportunities. For instance, engagement to Resistance's machine gun turrets was a full 19 percent below leader Halo 2. That's the difference between an exciting experience and one that, frankly, is a disappointment.

The failure lies in how protected the players are. In Resistance, one of the players' experiences with turrets in the first 90 minutes is from within a huge tank. In Halo 2, players utilize small, unprotected turrets that nearly ensure that they will be harmed, if not killed, if they remain on the turret for long.

The difference between engaging sniping and disengaging sniping also lies in the threats posed to the shooter. Halo 2, Battlefield 2142, and Ghost Recon all performed exceptionally here, scoring 12 percent, 18 percent, and 16 percent above benchmark averages, respectively. The level design ensures that players move forward as they snipe, frequently putting them in harm's way.

Call of Duty 3 was an exception. The game gives players an opportunity to distance themselves from the battlefield and locate themselves in a position where they can snipe unthreatened. The result is not only disengagement during sniping, but also during the period where players get into position, knowing full well that enemies are far away.

The pattern continues with the use of vehicles. Battlefield 2142's battle walkers failed to engage players until an equally powerful enemy approached, typically another battle walker. The majority of the time that players are in battle walkers, they are not strongly engaged in the game. Similarly, in Resistance, players emotionally disengage when driving the tank. Tank combat, without comparable threats, is not exciting or adrenaline-pumping.

What's interesting is that these threats don't always have to take the shape of enemies to engage players. Halo 2's Warthog is able to evoke sustained engagement and adrenaline, 17 percent above most vehicle benchmarks. The key difference we noticed is that Warthogs are never driven sensibly. Sure enough, high-speed driving, flying off jumps, and other generally reckless behavior consistently raised the level of engagement. In this case, players (and the vehicle physics) generated the threats, the challenge, and the entertainment of this novel gameplay.

Clients (and family members) always ask us if there's a single formula to compelling, engaging media, whether it's a video game, advertisement, or a movie. The truth is, there isn't.

But there are definite trends in what makes engaging and successful gameplay. At the end of the day, each of these successful games relies on superior execution and creativity to craft a uniquely engaging experience. Our big surprise is just how important the little things, like throwing a grenade, can be -- even more engaging than that epic and highly-scripted plot events.

Little things add up to more enjoyable experiences, higher Metacritic scores, and higher sales. In short, more fun. As we've seen, there are definitely some "rules of fun" that hold across these titles, and in some cases, across games in general. More interestingly, though, we're looking forward to seeing how future titles innovate and break these rules. As players expect more and more from their game experience, smart risk-taking in game design may be the only way to truly stand out in the crowd.

Games in study:

Battlefield 2142

Call of Duty 3

F.E.A.R.

Gears of War

Ghost Recon AW 2

Resistance: Fall of Man

Halo 2

Half-Life 2

Player responses measured:

Brainwaves (through dry EEG sensors)

Heart Activity

Breathing

Blinking

Temperature

Motion

Factors of analysis:

Engagement

Emotion

Adrenaline

Cognition

EmSense utilizes a next-generation, bio-sensory headset to measure consumers' responses to media. The headset measures brainwaves (through dry EEG sensors), heart activity, breathing, blinking, temperature, motion, and other physiological signals as gamers play.

Proprietary algorithms built on decades of research literature and empirically verified with EmSense's testing of thousands of test participants, process physiological signals to develop models of engagement, emotion, adrenaline, and cognition. Each represents a different dimension of the game experience.

EmSense also utilizes analytic and data mining methods designed to be completely blind and objective. "Event tags" identify when and where events, like player deaths, occur. This is correlated with physiological data, then aggregated and benchmarked against other titles. The result is an objective, detailed view into what does and doesn't work to engage players.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like