Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Road to the IGF 2022: Closed Hands is centralized around a terror attack on a fictional city, but its story spins out into past and future to fully explore the event's meanings.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series.

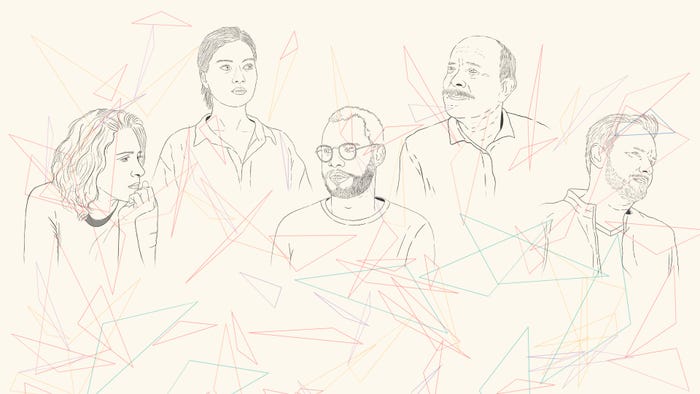

Closed Hands is centralized around a terror attack on a fictional city, but its story spins out into past and future to fully explore the event's meanings. What lead up to cause this to happen? What effects did these events have on people? Through five different perspectives, players examine the complexities around these tragedies.

Dan Hett of Passenger, developers of the IGF Excellence in Narrative-nominated game, spoke with Game Developer about creating a title around the long-term events and stories that lead to and from terrible atrocities, what drew them to convey the story in a variety of styles (texts, computer interfaces, phone calls), and why it was important that they chose to convey this tale going forwards and backwards through time.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Closed Hands?

Dan Hett, founder and director of Passenger: I'm Dan Hett. I'm a digital artist, writer, and game developer based in Manchester, UK. I'm the founder and director of Passenger, a small indie games company I formed to create challenging interactive fiction projects that had outgrown what I could do as a one-man band. Closed Hands is quite a personal project, in that I instigated and directed the whole game, as well as working as lead writer and programmer on the project. In total, eight of us worked on the game, though.

What's your background in making games?

Hett: I'm from a creative technology background, with games as a sort of component of that. Much of my background is creative tech and work on the more visual and arts side of digital, but this included a lot of games work over the years. Although games have always formed part of my creative arsenal, I've had a particular focus on them over the last few years via an increasing interest in experimental interactive fiction projects.

How did you come up with the concept for Closed Hands?

Hett: Closed Hands is actually quietly a follow-on project to some of my more personal projects, which I'd been working on over the last couple of years.

In 2017, I lost my younger brother Martyn in the Manchester Arena terror attack, and small introspective games and fragments of interactive narrative became one of the unexpected outputs I leaned on while processing a lot of what I went through (these can be found on my Itch.io page, playable freely online). The games were entirely self-produced and looked at grief, loss, and I suppose just the scale and magnitude of what I experienced as an individual. They were autobiographical, written and focused inward, small, and quite raw in place.

What Closed Hands does, really, is pull the camera away from me completely to begin asking bigger questions about what I went through—no longer looking at, for example, loss, but instead posing questions around why this took place, how an individual can reach a stage where they'd carry out an atrocity like this, and what it means to us as individuals, communities, and societies. Although Closed Hands is a work of fiction, it's undoubtedly drawn from my experiences since everything changed for me in 2017.

The core concept within the narrative is that the game focuses on a fictional terror attack in a fictional UK city, which I suppose might feel a little on the nose at first glance. However, the game intentionally never depicts the attack, or even goes as far as describing the nature of the attack. Instead, players experience the lead-up to the attack and the aftermath, sometimes a few minutes out, and sometimes a few decades on either side, from many perspectives. This game is about cause and effect, and networks of change and relationships between hundreds of stories that orbit the central event.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Hett: I tend to favor cross-platform and open-source technology where possible in my work, and chose the excellent Haxe programming language to build Closed Hands. Haxe is a superb language which allowed us to write a single codebase that generated builds for Windows, Mac, and Linux quite easily.

The actual prose within the game (which ran to around 130,000 words across hundreds of playable scenes) is powered by the excellent Ink engine by the Inkle team. Ink was an absolute revelation when I discovered it; it's a deceptively powerful but straightforward language for creating really clever interactive text structures. It's very close to written text with a bit of markup sprinkled in, so you still reach that zen-like flow state when writing in it as you would writing traditional prose.

I'm still tempted to open source our code at some point—I strongly believe in being a good citizen in that regard!

What interested you in telling a story that could be picked up in any order by the player?

Hett: We really wanted to tell a story in Closed Hands that not only moved between major and minor perspectives, but also went in multiple directions. The central event is the attack, but we really wanted to spiral out in both directions in order to add context and meaning to not just the reasons for the attack taking place, but its many effects on people in both the immediate and long-term aftermath.

We tried to focus different characters in different ways, too. For example, one of our characters, Marcus, is a young guy who gets almost accidentally caught up in the events of the story, and so his narrative arc begins with the attack and goes into the future in real time. Conversely, we have characters like Haziq, the father of one of the attackers, who we use as a vehicle to examine the long-term lead-up and radicalization of his son. Through him, we go enormously back in time first.

The game doesn't encourage a particular pathway, and opens with a single available scene for each of our characters - the moment each of them finds out about the attack. From there, and in the context of what the news means to each of them, our story expands both forwards and backwards in time to paint the full picture. We leave it entirely to players to decide which pathway they follow, or if they wish to change perspectives and explore.

What challenges came up in telling a story in this fragmented way? How did you overcome them?

Hett: Organizationally this writing process was a challenge, but not necessarily in a bad way. There were four writers on this project (myself, Dan Whitehead, Sharan Dhaliwal and Umar Ditta). Of the four of us, I'm the only person who regularly writes and codes interactive fiction, and so our challenge was a scale and translation thing, really—ensuring we were writing the right stuff so it fit together neatly and made sense, and not making early mistakes which would echo into eternity over hundreds of fragmented scenes. We're a mostly remote team, and much of this development took place during the early stages of the Covid drama anyway, which meant we really had to be organized from the offset.

Our process was to write linearly in hundreds of shared Google Docs documents, linked up by a really well-organized spreadsheet that delineated scene ownership, summaries, and writing progress. Within the linear docs, we worked quickly and roughly, adding notes and pointers to our big branch points or exit points.

The second phase of the process was for me to then take each scene and convert it to a playable interactive scene within Ink, which involved really pulling apart the prose and adding minor additional branch points, additional dialogue, or any other detail. I was doing this while also actively editing, which Ink lends itself really well to enabling. Overall, it was a good process, if a little labor-intensive. On future projects, I plan to write much more directly in Ink from the outset, ideally.

Likewise, what challenges come up when telling a story that connects five characters while also offering multiple routes through the game? How do you track it all, and how do you keep decisions feeling meaningful?

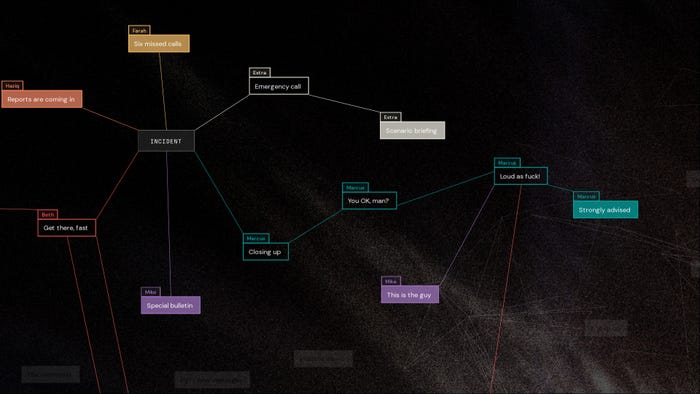

Hett: Planning! So much planning. Typically, as a writer I'm more of a by-the-pants kind of chap, but as a team we had to be much more organized than this, and long before any meaningful writing had taken place we'd already planned the narrative core in a fair amount of detail. We have five core character stories that spiral out of the middle event of the game, and dozens and dozens of one-shot flavor scenes from other perspectives, too.

Within this structure, however, the stories are reasonably linear, despite diverging and criss-crossing heavily, which helped a lot. We tried to strike a balance between giving the player meaningful decision points and a sense of agency within both the individual scenes and wider story, while also ensuring our stories were linear enough that we could tell the whole thing to them and keep it coherent.

Structurally, what we did initially was represent our story as a tree of connected nodes, which closely matches the game interface. We used Scapple, a simple mind-mapping app, initially just as a means of visually planning both the layout and relationships between scenes and characters. We also had a Bob Ross-style "happy little accident" during this process when I realized that the file that the software outputs was something I could parse directly into the game.

It took maybe an afternoon of hacking together to made our actual game respect the layout and links we'd put together in our planning sessions, which was not only a huge time-saver but also very handy during the rest of the development process when we were moving things around or adding/deleting scenes.

Closed Hands tells a story across many different means on top of traditional text: computer interfaces, conversations, IM's, phone calls. What drew you to have these different storytelling devices in your work? How do you feel they enhanced the experience and its themes?

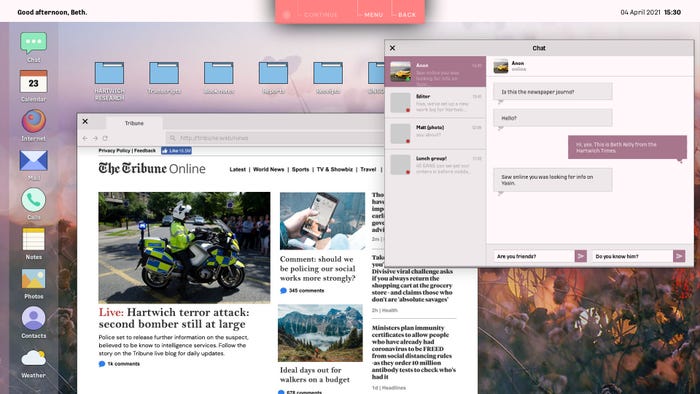

Hett: We chose to use interfaces very early on in the design process for a few reasons. Firstly, this is a very text-heavy game, with a perspective that constantly shifts between main characters and one-off scenes from other viewpoints. This means that using interface sections or other ways of interacting beyond just screen after screen of text is a bit more varied and interesting, if nothing else.

More importantly though, from a design perspective, each of the five characters really comes through in the design of the desktops. Our intelligence operative, Farah, uses a really stern formal interface littered with evidence and screens of code, whereas our young guy Marcus is clearly on a Mac equivalent while talking to his pals and checking the football scores. When we couple this design with writing careful dialogue for each character, the effect is quite pleasing.

I think there's also a truth to these sections in that there's no description or novel-style exposition anywhere—they're just pure dialogue between people, and so we see exactly what they're seeing, feeling, and experiencing.

There's also another cool reason these interfaces exist, which is that the original intention for the release of Closed Hands was to hold a physical exhibition to show the game to a real-world audience. Our launch partner was an arts and cultural venue in Manchester, HOME, who worked with us all the way through the process.

We planned on creating an installation of the game with five physical desks that the player could sit at, each representing one of the five characters—fully set-dressed and mocked up to feel like an extension of the screen. For example, our journalist character, Beth, would have a desk strewn with notes and files while using an old computer, versus our young guy Marcus who'd have a cool desk with a Mac on it and his camera and that sort of thing. We were going to create small versions of the stories for each machine, so they'd stay locked to the right interface and create a sort of character taster.

Sadly, the pandemic hit right at the wrong time, so the real-life plans never materialized and we switched to an entirely online model. C'est la vie!

What interested you in having several different writers working on the game? What sort of work goes into making your various styles and stories gel into a cohesive whole?

Hett: Collaboration is everything for a project like this, definitely. Although a lot of my work is solo, Closed Hands was not only far too big to take on alone, but also a project where I really needed additional voices and experiences in the mix. We kept things structurally cohesive mostly because we planned out in advance so carefully, and then in terms of the actual prose, everything went through me at the end during the conversion to interactive script, so I was able to mix it down into a form that matched all the way through.

More vitally though, with this particular game and subject matter, it was also critical to engage with trusted writers who represent and understand the stories and communities we look at during some of the character arcs. For example, we have a northern working-class character in the game, Mike, whose context and detail was definitely informed by writer Dan Whitehead and my experience growing up in similar cities and scenarios.

On the other side of the coin, it was critical to ensure that when depicting both South Asian and Muslim characters (like Haziq, and his network within the game) we didn't second-guess, instead working with talented writers who could ensure these stories were properly, accurately, and sensitively told.

What did you want to explore with this particular story? Evoke in the player with it?

Hett: I suppose the obvious main driver for me creating this project was through my personal experiences—wanting to not just say something to players, but also dig into this for myself, too. Speaking more with my artist hat on, creating work should be about you growing and evolving as a person and a creative too, as well as just broadcasting something to your audience, and I definitely think this process helped me as an individual.

In terms of player experience, and what we wanted to really say with this story, I think ultimately this game is trying to say that none of this is simple. We've really tried to represent the intense tangle of experience that comes with events like the one we depict, and the one I experienced. It's so easy to be reductive, regardless of your position or politics, and ignore the fact that you're one tiny part of a much bigger network of lives, communities, and stories.

I had an early reviewer come back to me after playing through the game, to tell me he'd not considered a lot of what we described in the story, and really that felt like a validation that we're resonating with people in the right way. I wouldn't necessarily say this thing is fun to play, and it certainly wasn't fun to write in places, but I do think it has value and says something to people. You'll have to try it yourselves, though.

This game, an IGF 2022 finalist, is featured as part of the IGF Awards ceremony, taking place at the Game Developers Conference on Wednesday, March 23 (with a simultaneous broadcast on GDC Twitch).

Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2022You May Also Like