Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How do you design for players of different skill levels at the same time? Game theorist Josh Bycer takes a look at how Nintendo designs the Super Mario Galaxy games to allow for players of all levels to be challenged, and contrasts that with the punishing Demon's Souls.

In my previous article on Darwinian Difficulty, there was a brief look, relating to Demon's Souls, at the concept of Subjective Difficulty. However, the concept of Subjective Difficulty is not restricted to brutally hard titles, and one of the most famous and accessible franchises of all time has been an example of this since 1996.

Before we continue, it's important to define two terms for the sake of this article:

Subjective Difficulty. Designing a challenge so that its severity is based on the player's skill level.

Safety Net. The degree to which the player can mess up and still succeed at the specific challenge.

Technically, we can argue that any challenge in a game is subjective by skill; someone who is a grand master at Street Fighter is not going to have the same problems with arcade mode as a player that has never touched a fighting game before. The key component in Subjective Difficulty, however, is that specific challenges are designed for different skill levels at the same time.

To achieve this, the player must have access to all (or most) of the available mechanics from the get-go. In order to design levels that allow different levels of skill to work, the player must have the option to use all the mechanics. If the levels are only designed around using one or two of the available mechanics, then it's not Subjective Difficulty, as both the novice and expert players are limited to the exact same thing.

With that said, there are a few considerations to understand about Subjective Difficulty. First is that unlocking mechanics as a form of progression is not considered Subjective Difficulty. If you have ever played a Metroid game, or the latest 2D Castlevania titles, there are always paths or sections along the main route that are blocked or inaccessible. As the player explores the game, they'll fight a boss or find a power-up that unlocks a new mechanic that can be used to enter the previously inaccessible area.

The point of contention is that it's not the player's fault that the area could not be reached, but the designer limiting the mechanics available. An expert player in Castlevania, no matter how good they are, will take the same path through the game as someone who is brand new.

Second is that the traditional use of difficulty levels is also not an example of Subjective Difficulty. Going back to the concept of the safety net, when the only difference between difficulty levels is stat-based (i.e., on "easy", enemies do less damage, but on "hard", enemies do more damage) then all the designer is doing is raising or lower the safety net based on the difficulty setting.

However, that doesn't mean that difficulty levels aren't a factor. God Hand for the PlayStation 2 has two forms of difficulty. At the start of the game, the player chooses a difficult level; this in turn affects the second layer. During play, at all times a meter in the bottom left of the screen displays the current difficulty level.

The difficulty of the game can fluctuate between Level 0 and Level Die (or 6) based on the player's performance. Taking significant damage or dying will lower the meter, which will drop the level down. The more the player avoids damage while continuing to make progress, the higher the level will rise.

God Hand

The level of difficulty affects two things. First, it affects how aggressive the AI is. The lower the number, the less likely enemies will counterattack, attack in groups, or use their stronger attacks with the opposite more frequent at higher levels. The second detail is that at the higher levels (specifically Level Die) more (and more difficult) enemies will show up in the levels, forcing the player to adapt. Going back to the initial difficulty level at the start, the only things it determines is the starting level of the meter and how high it can go.

Playing God Hand, the game attempts to match the player's skill level by raising or lowering the difficulty. Both a novice player and a skilled player are going to take the same path through the level, but what a novice player will be facing will be different compared to someone who is consistently performing well.

Another form of Subjective Difficulty is providing different variations of the same challenge. Games like Tony Hawk's Project 8 or Banjo-Kazooie: Nuts & Bolts each feature challenges with basic, advanced and expert goals.

Every challenge in the games has a bare minimum to complete to get a bronze medal, which is the easiest way to finish it. There are also more difficult ways to attempt challenges, which could earn players a silver or gold medal. For example: in Project 8, completing a race while placing at least 5th would be a bronze award, placing 2nd gives silver, and placing 1st while finishing the race in under 2 minutes awards gold.

These harder considerations are always available to the player to try if they want and be awarded accordingly, but getting the bronze (or silver) award is good enough to check that challenge off as being "completed".

This system is also popular in many smartphone games. A variation on it in the popular Cut the Rope finds players striving to capture three stars in each level -- which are not essential for completion, but are necessary for completists.

The Mario franchise has been going strong since the NES era. When the series transitioned to 3D with 1996's Super Mario 64, the game design changed profoundly. Before, every level was completely linear in its approach and mechanics; with the move to 3D, nonlinearity was introduced in the form of open levels.

The Super Mario Galaxy series and Demon's Souls are two sides of the same coin.

Obviously, that statement needs to be clarified. Both games give the player access to all of the core abilities of the character from the start of the game. In Mario, the plumber's abilities are movement-based (running, jumping) and his spin attack.

In Demon's Souls, the abilities and mechanics revolve around combat: attack, defense, managing stamina, and counterattacks. (It's worth noting that the player will unlock power-ups in the Super Mario Galaxy games, but these are usually confined to specific levels or gameplay scenarios.)

Now, the deviating point between the two series -- and why Mario is a better example of Subjective Difficulty than Demon's Souls -- has to do with the level design. In Demon's Souls, the player has access to all the available mechanics from the start and from the first stage is tested on all of them. In Mario Galaxy, the player has all the available mechanics and is not tested on all of them, but can use them if necessary.

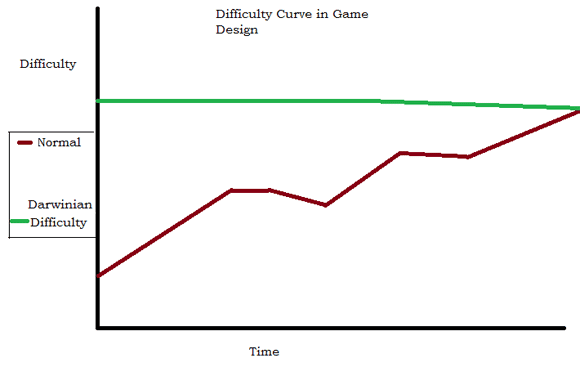

Referring back to the concept of Darwinian Difficulty, the player is introduced from the very beginning of the game to all (or at least most) of the mechanics and is then tasked with using them effectively. Here is the difficulty chart from the previous article, as a point of reference:

In both types of games, the player has all of the gameplay tools from the outset. In a game with Darwinian Difficulty, the player is asked to use them all; in a game with Subjective Difficulty, the player may or may not use them at any time during the game and still play effectively. The difference between the two allows different skill levels to experience the same content, but handle it in different ways based on their expertise.

The first level in Super Mario Galaxy 2 is a perfect example of level design built around Subjective Difficulty. About halfway through the level, Mario has to use ascending and descending platforms to climb up a hill. Expert players can use a combination of Mario's triple jump and wall jump to get up the hill in a fraction of the time a novice might take.

There's another example near the end of the level. The player is tasked with maneuvering over bottomless pits by traversing moving platforms. A novice player can get through this entire area using nothing but Mario's basic jumping ability, and be tested with this design. However, an expert player can simply bypass the entire area by performing a long jump across the pits.

Both the novice and expert player have the same challenge, but handle it differently based on their skill levels. Unless the novice player has read the manual or played Super Mario Galaxy, at that point they probably have no idea how to perform a long jump, and that's perfectly fine. The first mention and test of using the long jump ability comes later on, at the same time Mario gets the cloud power-up. The in-game introduction to each of Mario's abilities is signified by a signpost showing the player how to perform the mechanic, followed by a simple test.

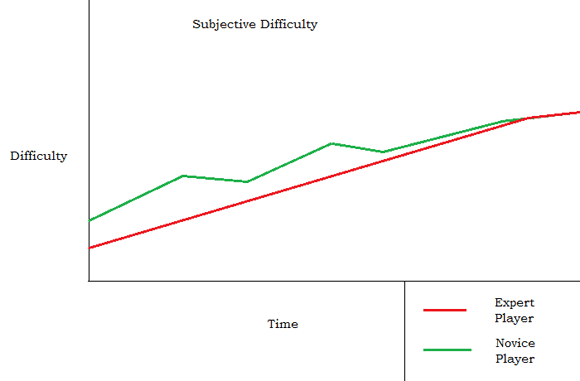

The following graph shows the difficulty curve of a subjective game:

For the sake of the article, this chart only represents the normal content of the game; we'll touch on post-game content further on. As you can see, for the novice player, the game's difficulty curve follows the normal progression -- a steady progress higher across the chart with a few dips here and there. Meanwhile, an expert player starts out lower on the curve and makes a continual progression.

Now, you may be asking, "If the expert player is taking a harder course, shouldn't the curve be higher than for the novice?" The reason it isn't goes back to the concept of Subjective Difficulty. Even though the expert player is doing something harder, their skill level at the game makes it easier for them. For example, if we ask someone who has never lifted weights to lift 40 pounds, and a professional weightlifter to lift 60 pounds, the novice is going to struggle due to their inexperience. However, the weightlifter, used to lifting much heavier loads, wouldn't even sweat.

As the game progresses there should come a point where the difficulty curves converge indicating two things:

1. The novice player has reached the same skill level as the expert player.

2. The game is now challenging both groups with the same content.

At the end of the regular content in Super Mario Galaxy, players are expected to fully understand Mario's move set, and are tested on it all in one final stage. The same philosophy of designing the levels is still used, but now the game is more akin to Demon's Souls, expecting the player to make use of all of Mario's abilities to win.

Novice players who do manage to beat Super Mario Galaxy will find that the game has changed for them. Now that they understand all of the different abilities Mario has, they can now use them anywhere in the game. It's similar to how in an RPG, a higher level player can return to a once difficult spot and utterly demolish it -- but what's leveled up is the player, not the character.

Before we talk about the pros and cons of Subjective Difficulty, we need to take a look at how post-game content worked in Super Mario Galaxy 2, and how it plays off of the concept of Subjective Difficulty. Fitting into the theme of developing level design for different skill levels, there are special coins hidden in each level, most often placed in harder-to-reach areas.

Each coin found will unlock a comet challenge, which sends players back through older levels with modifiers to make them more difficult. For example, in the first world, the comet challenge requires the player to run through the first level with a timer counting down, requiring the player to use the shortcuts to win.

Novice players will not have access to these challenges, as they are not good enough yet to reach the special coins, but the expert players should find them relatively quickly. The comet challenges aren't required to beat the game, as players will earn more than enough stars through regular play to reach the final stage, but they are there for expert players who want more.

As novice players become more skilled at the game, they will start to find the hidden coins and unlock comet challenges. Like with the regular game content, novice players should eventually reach the same point as the expert players, allowing them to tackle the additional challenges. Expert players, however, don't have to wait, and if they are good enough at the start of the game, they can begin comet challenges relatively early in the game.

The advantage of Subjective Difficulty revolves around accessibility. Games like Super Mario Galaxy allow the designer to have their cake and eat it too, in a sense.

On one hand, the game starts out simple enough, easing new players into the game without throwing them right into the thick of things. On the other hand, this design style allows expert players to be rewarded with areas suited for them from the beginning, and offers additional content to test their skills.

Now, the problem is that Subjective Difficulty is that it's hard to pull off and requires a different kind of design. In a normal game, the designer will look at each challenge progressively, with one group in mind. You know that a challenge in the beginning of the game is going to be easier than one found later on, but Subjective Difficulty is different.

Essentially, the designer will have to design each level for different skill levels at the same time, requiring more time to create the content. Because of this, there are usually more shortcuts and hidden areas in games with Subjective Difficulty which allow gamers to fully use the mechanics. Creating this additional content requires an extensive understanding of the mechanics of the game, to set up challenges that can be handled in multiple ways at different levels of skill.

As a designer, you also need to rank your mechanics in terms of complexity to understand the best order for the player to understand them. Going back to Super Mario Galaxy 2, the designers slowly introduced each mechanic officially to the player through set challenges, giving ample time for the player to understand one mechanic before introducing another. This leads to asking questions like, "What is more complex to use, a triple jump into a wall jump followed by a spin jump, or a sideways flip, into a spin, followed by a wall jump?"

Subjective Difficulty, like Darwinian Difficulty, requires an expert touch to achieve. When pulled off, it allows gamers to enjoy the game regardless of skill level, while seeing improvements in their skill over the course of the game. By keeping multiple groups of gamers engaged, the game will attract a larger audience without having to simplify the design of the game. Ultimately, the goal of Subjective Difficulty is that the novice players should achieve a full circle of play, after finishing the game they can replay the game again, but using their improve ability to see the game in a different light.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like