City management, mayhem and Sid Meier's wisdom: Making Civilization VI

6 years on, Firaxis is preparing to ship Civilization VI. Here, producer Dennis Shirk reveals how the game's design incorporates everything from Sid Meier's 33/33/33 rule to a novel "Mayhem" mechanic.

The world probably doesn't need another Civilization game. They're still playing the last one.

Sid Meier's Civilization V shipped in 2010, and to this day it still regularly appears in the top ten games on Steam in terms of player count, falling beneath heavyweights like Dota 2 and Counter-Strike: GO but above recent, highly popular releases like Fallout 4.

Six years on, Firaxis is preparing to ship Civilization VI, with Civ V expansion designer Ed Beach in the lead design chair. From a game developer's perspective, it's intriguing to look at how the venerable strategy game's design continues to evolve -- especially since it's building on a foundation laid 25 years ago by the original Civ.

At E3 this year Civ team producer Dennis Shirk noted that while there are still a lot of people playing Civ V, the changes made to that game's design by its lead designer (Jon Schafer, now president at Conifer Games) during the course of production wound up revealing yet more fundamental Civ design problems the team wants to fix -- starting with cities.

"A designer can get wrapped up in his own head about how awesome his design is, but if he puts it out there and nobody gets it, then that's a failure."

"Unstacking the cities is kind of the cornerstone of the whole thing," said Shirk. "After Jon Schafer had gone to one unit per tile [with Civ V], it exposed another part of the game that wasn't very interesting, which is that everything gets built in the city center. As long as you've unlocked it in the tech tree, you're building it and it's just going in the same place. That's all it is: a spot to dump all your buildings, and all your Wonders, and so on."

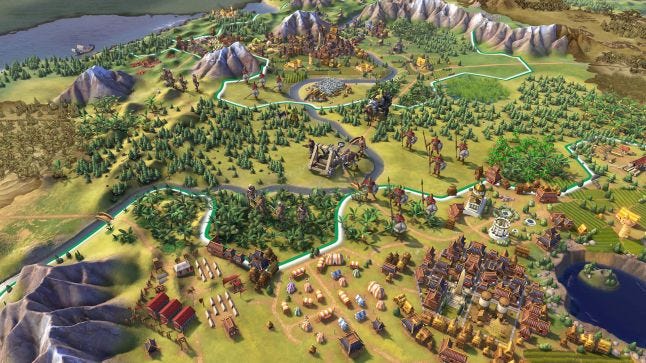

With Civ VI, says Shirk, "Ed wanted to change all that. He wanted the game to be about the landscape. He wanted the map to be just as important as anything else in the game." So he designed a Civ game that asks players to actually lay out "districts" in the tiles around their cities ("it's the first thing he prototyped in the game"), and gives them bonuses based on the landscape.

Mountains can be inspirational, for example, so the religion-focused district (the "Holy Site") where you build shrines and temples gets a bonus if it's placed near a mountain. Researching technologies like sailing gets easier if a player's civilization is near the ocean. Managing cities gets more complex, and -- Firaxis hopes -- more interesting.

But that also raises an interesting design question: is it possible to simulation human civilization with too much complexity, to the point where it isn't "fun" anymore?

Shirk suggests developers facing such concerns "follow Civ's most basic design guideline, 'Never have it be complicated until the player is ready for it to be complicated.'" So for a Civilization game, that means starting players out in every new game with just two units: a settler and a warrior. That means the player only has to make one decision: move a unit or found a city.

"The trick, I think, especially to a game like Civilization, and it's a place we've stumbled in the past, is pacing," says Shirk. "I'm sure you remember way back in Civilization V, the very base game, the last third of the game wasn't very interesting. It felt like a very empty space, just hitting 'Next Turn' a lot. So it's that kind of pacing that's always the biggest challenge."

You've got to have a little mayhem

To fix the pacing problem and spice up the base game a bit, Beach did something with the Civ V expansions that fellow strategy game designers may appreciate: he added a little mayhem.

"There's an AI system in the game, it's actually been in there since the expansions when we first introduced it...it's called a 'Mayhem Level,'" says Shirk. "It's actually a super interesting mechanic that Ed came up with. If the game is not achieving a certain level of mayhem, which means something in the world is going on that's causing some problems," then the game AI starts acting up and making moves to make things interesting.

"You don't want huge long times of prosperity," adds Shirk. It makes for a boring strategy game, and it doesn't challenge players to learn the game's systems.

"You have to turn some knobs and make sure the mayhem stays at this certain level. You don't want anything way up here. You don't want anything way down here. So it's a really interesting way of making sure that there's always something that's going to pull the player away from what they're doing or what they're focused on all the time."

Here again, we return to an interesting central design goal for the Civ team: to shake players out of their routines and keep them from playing on autopilot. And that begs another intriguing question: how do you know how far is too far when you're revising your game's design -- especially when your game is the next big Civ?

"Every designer coming in, they have to walk that fine line," says Shirk. "'Will I upset the apple cart this time around?'"

Sid Meier's 33/33/33 rule of sequel design

Even if you aren't working on a Civ game, you may get something out of the advice Shirk says is common wisdom at Firaxis: Sid Meier's 33/33/33 rule of sequel design.

"You want 33 percent of what's already there, existing, 33 percent improved, and 33 percent brand-new in terms of mechanics," he says. "That's something he's spread throughout all the franchises at the company. You saw that with XCOM 2, you saw that with [Sid Meier's Civilization: Beyond Earth expansion] Rising Tide when that came out. We try to keep that in all the games we make."

That matches up well with what Mafia III lead Haden Blackman told Gamasutra last week about the value of limits, especially for game developers. Box yourself in with a set of reasonable constraints -- the 33/33/33 rule, for instance -- and you may have an easier time focusing your efforts on the things that will help your game shine.

But Shirk cautions that it's also important not to get too attached to your own ideas about a game's design, and to solicit community feedback early on.

"A designer can get wrapped up in his own head about how awesome his design is, but if he puts it out there and nobody gets it, then that's a failure," says Shirk. "I'm sure you've heard of Frankenstein, and that's been a staple of Civilization, especially throughout many of the last versions of the game. If we didn't have that core group of fans, just constantly giving us feedback as Ed is bouncing ideas back and forth really trying to find that great balance, I don't think Civ would be as good as it is right now."

[Frankenstein, incidentally, is the name of a long-running community of external beta testers who help put Firaxis games through their paces.]

Of course, many developers are good about seeking outside feedback on their games early on -- that's why Steam's Early Access service was born. It's already given rise to at least one notable strategy game, too: Firaxis expat Soren Johnson (who served as lead designer on Civilization IV) learned some notable lessons in launching his own strategy game, Offworld Trading Company, on Early Access last year.

Shirk speaks well of Early Access, especially for developers who are trying to bring game ideas that are novel or untested to life, but says that making a game available for play (and purchase) before it's done would probably never gel with Firaxis' development process -- especially on a Civ game.

"I worry that when you have such a large team, and you have such large expectations...if you had something like Civilization VI come out on Early Access, and have it not be ready for prime time, I think the backlash could potentially be great," says Shirk. "I think if you're coming out with a brand new concept, a brand new game, especially Soren with Offworld Trading Company, I think the options for Early Access are a lot more powerful because there are no pre-set expectations going in with what the game is or how it should work."

The weight of expectations is also pushing Firaxis to ship Civilization VI with a number of established Civ systems, the sorts of mechanics (like religion) that have previously been added to Civ games post-release through expansion packs.

"Jon Schafer worried if we brought everything forward, for example, from Beyond the Sword then it would be a little overwhelming. So he had to take a lot of things out. He left religion out of the base game, that kind of thing. Ed didn't want to go down that path this time," says Shirk. "Fans already have this very high expectation of what Civilization means. They have things that are really comfortable for them, that they really love doing. He wanted to make sure to bring as much of that forward as possible."

That means Civilization 6 devs have to teach those myriad mechanics to new players, too, because every Civ is someone's first. It's interesting to note that Firaxis aims to do so by falling back on an old-fashioned, extra-large tutorial here, one that gives new players a guided tour through the game's various systems and mechanics. It's optional, of course, and is meant to augment the tooltips, automated advisors and other teaching tools that are woven into Civ games.

"This is probably the biggest base version of the game that we've ever shipped before," Shirk says, and while he acknowledges that "we do have some crunch time" he's keen to point out that it's kept to a minimum because of what he describes as one of Firaxis' chief virtues: managing staff time well.

"We're starting to be an older studio. Our baby credits are going up and up and up each year because we've got a lot of senior artists, senior designers, senior engineers that have been with Firaxis for a while," says Shirk. "So if we don't have that great home life and work balance, the games are going to be crappy because everyone's going to be miserable. That's one thing at our studio that I wish every other studio would be able to do. You've heard scary stories from other studios about how that's not necessarily the case. It goes a long way. It sounds stupid, but a studio that actually puts family first is a happy studio that makes great games."

Read more about:

event-e3About the Author

You May Also Like