Building science fiction worlds with Big Robot founder Jim Rossignol

Rossignol, who helped create titles including Sir, You Are Being Hunted and The Signal From Tolva, breaks down his approach to sci-fi.

Jim Rossignol is a writer and game developer best known for his work with Big Robot: Sir, You Are Being Hunted, The Signal From Tölva, and The Light Keeps Us Safe. Developed by a small team, the Big Robot games all have a unique science fictional tone to them that strays away from the power fantasies of our biggest franchises and digs deeply into sneaking, strategic encounters, and the despair of wide-open spaces.

I sat down to chat with Rossignol about how he thinks about these worlds that he has had a hand in designing. This interview walks through both big science fiction ideas and the practical realities of making science fiction worlds as collaborative ventures. This interview travels from J.G. Ballard to weird England and a lot of other places in-between.

Game Developer: How do you define science fiction?

Jim Rossignol: I always liked Steven Shaviro’s “ghosts of the future” definition, the idea that science fiction is us being haunted by things that haven’t happened yet, but I think for me it’s more about the craft than that. Generally my interpretation of science fiction comes from reading loads of Ballard in my twenties. There's an amazing collection, which I buy occasionally and give away to people. Actually I have it on my desk at the moment, funnily enough, A User's Guide to the Millennium, which is a collection of his reviews and sort of criticism generally. He talks a lot about his idea that science fiction is the most important literature of the study of the 20th century. And I think whatever science fiction becomes will be the important literature of the 21st century as well. I think there’s a lot to his sort of general thesis of that science fiction is the mythology of modernity, and I think about what that means, how it analyzes our ideas, and where we are going.

For me, the standout piece of writing in that book is where he talks about Star Wars, and he's incredibly dismissive of it. Ballard very much talks about, you know, how it’s very derivative, very thin, it’s visual design over any kind of message or originality of ideas. But also one of the things he talks about in that book generally, and which I'm not sure whether I agree with or not, is this idea that the visual image is going to erode and eventually completely subsume and destroy literature as a written form. He says that the visual image is just becoming more and more powerful. And the power of the visual image is sort of critical to the stuff that Ballard talks about in cinema, and particularly in science fiction. One of the things he touches on in the Star Wars review is the fact that Star Wars was not necessarily any kind of threshold in terms of literature or writing but in terms of what the technology, what the visual spectacle enabled it to portray.

The thing he enjoyed most about Star Wars, this writer of apocalypses, was the fact that it was that the technology was sufficiently advanced to portray technology in decline, like the sort of the rusted, knackered nature of the Millennium Falcon and the fact that the best the best times of the Jedi and all that kind of stuff is behind them. I think that's kind of the striking thing for me, because so much of what science fiction is has become wrapped up in our technical ability to display stuff on a screen and what we can portray that those two things have become so enmeshed that it's really difficult to separate them. I think that science fiction is as often about the evolution and progression of the image and what it is that we're able to display as it is the sort of conceptual literature that Ballard talked about.

I was thinking about this when you mentioned you wanted to do this interview. I was thinking about what I would say about the way we use science fiction tropes in our own work and how that came about in the Big Robot games. It struck me that while the best science fiction is literature in that it's about something and it speaks to human conditions, a lot of what we did was about coming up with a specific image and then building something around it. So we found ourselves trapped within that thing that Ballard identifies, which is the visual image being more important than what the literature says or what the conceptual take of the science fiction story is. In all three Big Robot games, Sir, You Are Being Hunted, The Signal From Tölva, and The Light Keeps Us Safe, we began with imagery. All of those games could be said to be “about” something, and I think what’s been most interesting is people’s interpretations of what they’re about. But none of them began with that, in the way that you know, literature stories will begin with a conceit; an idea; a situation; characters. In the beginning it was not the word; in the beginning it was like a specific image or a sort of visual motif that we wanted to get across.

Explore, fight, and survive in The Signal From Tölva

For Tölva, the idea of alien highlands and a kind of spookiness with blue skies as the background, that sense that a space with blue skies and rolling grass could still be haunted and perhaps slightly disturbing, was the thing that I was looking for. Which is definitely too subtle a thing to interrogate with video games, right? A few people kind of went, “Oh, yeah, I kind of get it.” I don't think anybody got it (laughing). But, you know, the fact that was the initial thing that we were reaching for was interesting. It comes from this march of the visual image of what we can portray, and even in the tiny scale that we do science fiction, we were caught in that. What can we portray on the screen? What can we do technologically? What can an indie studio do to create really potent stylized science fiction imagery? I think all three games manage it really well, and I'm really proud of what we've accomplished with those.

I think for someone who's a writer and enjoys writing and telling stories, I don't tend to use video games to do that. And I think that one of the reasons for that is that science fiction, to me, means incredibly potent imagery. It's the image that is always most important in a sentence. I often talk about science fiction films with people, and they talk about the themes and the characters. That's never what really hit me. It's always a specific frame or a specific scene in a movie. I always think about the Blade Runner scene after the opening sequences where he goes back to his apartment and he drinks or something. He leans on a balcony, and you see the cyberpunk city, you know, flying cargo shoom past. For me, the whole film can be discarded, and we can just keep that single scene.

I almost feel that most science fiction comes down to some incredibly potent piece of imagery that I'm really excited about. I like science fiction that can be directly related to human lives and characters, and I enjoy that as much as anyone you know. The best movies do have something to say; the best games have something to say. They’re an extraordinary code of comments and toolkits to examine our lives, but the things that always stick with me are things like the lightsaber duel at the end of Jedi or even a single shot or frame: Vader and Luke, with their sabers crossed. Discard the rest of the film and bam, you know, that's the thing that I'm excited about: the image. That's what science fiction is in my head.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about singular images, because a lot of video games start with action. Many people who theorize games on the development and the academic side begin with mechanics and what they can do. Can you talk about building a set of actions out of an image?

I've talked about discarding all that stuff, and the reason you can discard that stuff is because the single image implies it all, right? If you get a single painting of a spaceship turning fast through an asteroid belt, the motion is implied, the action is implied that they're being chased. Why are they racing through the asteroid belt? That becomes this imaginative spark that everything can balloon out of. I tend to obsess over the single frames because they often imply a whole bunch of different directions that you could have gone in. That’s super true for games, right?

So for Tölva, for example, the image that me and Tom kept coming back to was this short sequence. It’s a shot used often in cinema. You’re walking, and you come over a hill, and you are third party to something happening below. The way we did that shot in Tölva is that about 10 or 15 minutes in you come over the crest of a hill. We'd orchestrated it so there would almost always be a fight between two of the factions around this huge carcass of a robot, this great skull that's been shot through the head with the exit wound at the back and the hand lying off to one side and stuff. There's a battle around that. It was just as important to have that as a visual scene for us than it was to know what any of the gameplay was going to be. But I felt like taking that as a kind of target moment/scene/image meant that the characters had to move, they had to be able to be far enough from the action to decide whether to engage with it or not. They weren't being dropped in a Doom-like “things rushing at you” environment. They were in a wide open space where they could look at it with binoculars and say, “Do I want to get involved with that? Or do I want to just watch to see what the outcome is?” You had to have that sense of space. So immediately, you know, it's an open landscape; that's the best way to do that.

We had to work out what combat interactions work. Are you alone? Can you go back and get other people? Are there other allies in that space? Interrogating that single image implied the mechanics that we wanted from it. But of course you end up being limited in the way you can do stuff as much as you are enabled by tech.

Sir, You Are Being Hunted, for example, started there. Tom Betts had done some stuff with us before on a commissioned game, and in the background for that he'd been working on procedural generation stuff. And one of these, one of the prototypes that he'd done was one where it was essentially infinite terrain. Now there's some argument whether it was truly an infinite landscape generator and what the term “infinity” meant in that sense, but you could walk forever in a single direction and it would just continue to generate landscape, which was a really cool thing. We didn't do much more than that, but the initial take for Sir, You Are Being Hunted was that you would be being continually chased from behind.

The machines in Sir, You Are Being Hunted are terrifying and damn stylish

The Eternal Cylinder has come out now, and I don't know them well enough to ask this stuff, but I do wonder whether their initial concept for that was that the cylinder just kept rolling, and you had to keep moving and you sort of generate that landscape ahead. But when we came to do that with Sir, we couldn't get in enough gameplay, while also using the CPU to generate the landscape.

So the hunted-ness of that becomes “you generate an island, and then you have to move around within it.” Then the gameplay necessarily changes to enemies putting traps down or patrolling to try and catch you, rather than knowing where you are and relentlessly following you. We knew that we wanted to do this chase across a British countryside, and we knew we wanted to use procedural generation to do that. But you can see how these technologies and ideas might have gone a different way. If you were fleeing all the time in Hunted, and you knew that you were being continuously chased and the landscape was spreading out ahead of you, then it would have been a lot more about running and motion and stamina. Whereas when we realized that we were limited within that, that the structure of it changed, it became more about stealth and using the undergrowth, creeping about in the long grass, hiding behind hedges, using physical cover.

So starting with any visual image, you can go off in a bunch of different directions. And we have gone off in lots of directions in the way we've designed stuff, but when you hit particular walls, whether they're design walls, tech walls, then you find yourself confirming the direction you're moving in. That will decide for you in lots of ways what the actions are going to be. This is the super kind of writer-y thing to say, but there's a William Burroughs quote, I paraphrase horribly, he talks about how when you're in the flow of writing, it comes like dictation and you're not really writing at all, but you're you're writing it in the sense that you're physically doing so but some other unconscious or higher entity is dictating it to you.

I've always felt like it's a function of all the inputs onto the writer that ends up producing the writing. You're mediated by what's going on in your brain? It isn't a pure imaginative act, right? You add. The same ends up being true for game design. You're hitting lots of inputs. Some of those are technical limitations, some of those input limitations. And then all the design expectations. The game ends up being a function of all of it.

I associated most of the games you have worked on with a sense of inhumanity or the minimization of the human. You generally make worlds that are hostile to people, or where people are wholly absented. Is that a purposeful decision? Can you tell me more about how you get to these designs?

I think it may have been a Harvey Smith quote, where he talks about the best stealth games being disempowerment fantasies. I don't think that's true of Dishonored, because you're very clearly a superhero. But I think there are suggestions in stealth games like Thief where you’re fragile. I think the disempowerment is the thing that's exciting, right? I mean, this is tied up with sex and ego and all kinds of all kinds of stuff where how a game treats us psychologically, and how we want to use it psychologically, is connected with empowerment and disempowerment and tidying up making a mess. Those kinds of dichotomies. It always struck me that both disempowerment and the decentering of the player are more interesting than the hero's journey player-centering empowerment stuff because they're exciting and they give you a sense of vulnerability and a lot of that comes from how you interpret the game world.

For example, this is an interesting bit of design evolution. In Sir, You Are Being Hunted, there is a balloon with a robot and a light that randomly searches around. That balloon randomly drifts across the island. There's no AI attached to it. It's just code that picks a point, goes there, and then changes its attention to another direction. And yet, it happened to cross people's paths enough in that game that people were certain that it was seeking them out and was following them. Which of course, it never was, but it was this entirely like psychological kind of thing. So when we did The Light Keeps Us Safe, we created a large spider-craft that does come after you. It does know where you are and is always coming towards you. What's interesting is that there's almost no difference psychologically between the random movement of the balloon and the spider-craft. In both cases, I think the fact that there's no way to destroy it, there's no way to stop it mattered to players.

I don't necessarily like games that are particularly sort of masochistically challenging, like the sort of instadeath platformers or even the Souls games, both of which depend on repetition. I like the sense of almost an overarching psychological horror that comes from disempowerment and knowing that the entire world is not for you, and is not hospitable to you, and is out to destroy you. I think that there are not that many games that really get that, especially not ones that have quite an open space. There’s a default towards increasing power curves.

A glimpse into The Light Keeps Us Safe's procedurally generated apocalypse

I think disempowerment is particularly interesting in science fiction, because science fiction gives us the possibility of enormous structures and sets systems that are so beyond what humans can be. We did a bunch of fiction surrounding Tölva. Some of that I worked on with Cassandra Khaw, writing incredible stuff. Part of the fiction in Tölva is that humans have basically been abandoned by their machine progeny, who have realized they can build much faster structures, more complicated things, and can do more interesting stuff if they decouple themselves from humans completely, which is less machine uprising and more machine apathy. I am not sure which is scarier. What if the machines that are supposed to care for us couldn’t be bothered to do so?

One of the ambiguities of Tölva is who you are. Are you just an AI? Or are you a human who is jumping between the control of these robots remotely? I mean you are, because you are as the player, but are you in the game world? That’s never made clear, which I really like in terms of what that means for your accomplishment and the way that the story resolves. I guess that's true of all three games actually, in that it's not really clear who you are. You're talked to by a butler who addresses you as Sir or Madam in Hunted, but what does that mean? And again, the masked character that you are in The Light Keeps Us Safe. It's obvious that you've been stuck down there in the bunker, but why? Why alone? I love that kind of sense of the disempowerment of not knowing and just piling up what we always called “vectors for peril,” rather than giving the player more guns, more health, more shields, more spaceships. Instead we just give more ways to die, horribly (laughs).

I really like how science fiction games can not be fun, which is a terrible thing to say about my own games! But I see it in a wider sense. I played EVE Online obsessively for years, and it's not really fun in any kind of classical definition of that word. The science fiction setup that it produces as a result of the commitment and kind of level of grind to it is, I think, the closest we have come in a game experience to what some kind of future space science fiction reality might be like. It’s very human, and the psychological experience links back to Ballard: long periods of boredom punctuated by extreme horror is most people's experience playing EVE, and perhaps life generally. In EVE you’re just pottering around mining asteroids, doing grindy bullshit for hours, then suddenly dying a fiery death at the hands of other players.

I love that about it, and I think it's the reason I ended up writing so much about that game. It got that kind of sense of a possible future across. My own fantasies of science fiction existence have never been more closely realized than in playing that. Living in that pocket of video game. We would spend hours stalking enemies and then there'd be a fight that lasted thirty seconds. That payoff was enough because of the systems and structure of that game pre-loaded everything with significance.

Your games have a strong feeling of the UK science fiction tradition. Can you say a bit about the cultural influences that go into your work?

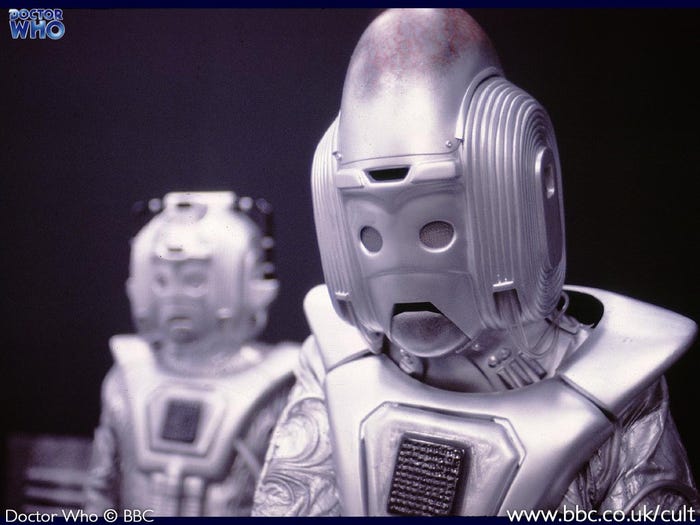

I think there is probably a sort of truism about the UK pop culture psyche that is gone now and is not available to my or future children. We're in a kind of like, post scarcity reality now of just being able to access an extraordinary array of TV, games, books, comics, but it was a period of scarcity growing up in the 1980s, and certainly in the 1970s. Gleaning glimpses of science fiction from what was on one of the four broadcast channels in the UK of an evening and then being horrified by it was an absolutely defining experience for a child of my age, and I'm sure that's true for any of my peers growing up in that period. For all their goofiness, there's some genuinely disturbing stuff in the '80s and earlier Doctor Who that was definitely wrapped up with childhood fever dreams and creeping downstairs at night when I shouldn't have to see some horrifying '80s science fiction things that would have been shown later in the evening.

I can remember my parents having a few episodes of, I think, but am not sure, The Prisoner on tape where it had been rebroadcast or pirated or something? I'm watching those and not understanding, having no idea what they even meant, which is disturbing on its own. Watching it a few times and kind of going, “Oh, that's so weird” and then being able to buy the DVD box set like 20 years later, I go “all right, I sort of get it now.” There's quite a lot there in terms of how that loads up the imagination in a distinct way. Fragmentary and not plugged into any large corporate ecosystem.

I think there's a slightly deeper sense in the UK of the threads that run through history that plunge directly into the present and then into the future through the general eeriness of the UK. The sense that there is an eeriness and weirdness in science fiction takes directly from a tradition of eeriness in folklore and landscape and the way that people have related to the space of the UK and interpreted the environment and the stories surrounding it. I think that all cultures have a kind of storytelling history of threat and strangeness because that's the kind of thing that kids need to be able to understand and relate and deal with, but the UK’s particular flavor of that is one that's ended up influencing lots of creators in a noticeable way, and there's a sense that there's a kind of provincial-ness in that as well, which I think is really important.

Enduring sci-fi series Doctor Who birthed iconic foes such as the Cybermen

There is obviously a kind of centralizing imperial thread with a lot of modern culture, like the sheer number of movies that are set, even if they're science fiction or weird in some way, in LA or New York or London. But I feel like there's a sense that in the stuff that influenced me that those stories could come from other places. You know, market towns in England or places that were not central locations. That kind of thing crops up again and again in British homegrown literature and in the sort of television we watched and things like that. I've kind of wanted that for the things that I've made as well. I want to kind of have a provincial-ness.

I like the sense that those places and stories are valid unto themselves. One of the things that I dislike is the “visitor from one privileged location to another” plot. People doing time travel from our present day, or that sort of Alice character who you can relate to because they’re just somebody from LA who happens to have gone into the Appalachians to say “look at these weird people that live up here.” I generally dislike that and I do prefer a story that's told on its own terms about those people within that context. I wonder whether that's why I've been super ambiguous with the character designs in the games because I don't want them to necessarily be about a normal or heroic guy and then suddenly he's caught up in something new. Instead, we don't know who our characters are, but they are probably from that world. They’re probably somehow embedded and have some context within it, and they understand it and relate to it on that basis, and so the lens for the science fiction is not necessarily discovery but coping.

Tangentially, one of my outstanding negative memories in life was going to see the Masters of the Universe movie and having He-Man and the other characters just fucking about in LA. Even as a kid (and I was quite young at the time) I was furious. I was so angry at that. Like no, it must be set in Eternia right? That world has nothing to do with our mundane existence. They live in a fantasy world that is complete unto itself. To have them running about in car lots in LA just made childhood me just unbelievably angry, to the fact that even to this day I react badly to original fantasy-worlds-crossing-over-with-real-world conceits in any kind of fiction, but particularly science fiction or science fantasy. (laughs)

Your settings are all pretty singular and well-developed. Do you have any tried and true methods for building out science fiction worlds?

I think all writers have themes that they continually return to, and I know I do. “Escape” is a really key theme for me, but not, I should stress in that Alice In Wonderland way, but there are other ways escape appears in science fiction. It’s usually the escape from, and not too, that I think is important. Obviously, there are other things I've worked on that don't support and can't be related to this, but even in Ancient Enemy that I did with Jake Burkett, the story has an imprisoning loop and escape built into it. I kind of almost accept that if I'm going to write something it's probably going to support that theme, in some sense. My kids find it extraordinary that my favorite movie is The Truman Show, but that’s because of that final scene: he goes outside. He literally escapes his reality, which is the most powerful scene or image for me in anything. “Oh, actually this reality isn't real, I'm just gonna step outside.” Which, perversely, is one of the reasons I enjoy but don't really like The Matrix movies, because I feel like they used that so cheaply and it got sold up in a kind of like… well, escaping the Matrix wasn’t the pay off, it was the setup.

Yeah, so basically, again with the Ballard thing, you know that kind of like “be faithful to your obsessions”. That was one of the first things I read by him was that quote, “Be faithful to your obsessions, let them guide you like a sleepwalker.” That's how creative life works, right? You work out what you're obsessed with and you follow those lines. Equally, everything I've made has needed to be super, super collaborative and I can't really take responsibility for any of it.

The fact that there were those collaborative situations meant that I had to come up with narrative conceits that worked for me, but that also worked for something that was already established through a group consensus. It's about finding ways that the things I'm esoterically and personally obsessed with could find a home in something that other people have to sign off on and understand and make. I think the process really is conversational, right? It is about saying, “I really like these ideas and I think this is funny or dark or horrifying or beautiful,” and seeing how other people react to that and how they will ruin or enhance or however else when they incorporate it within the project you're working on. I love producing lots of different material and seeing how it gets incorporated and seeing how people say, “Oh, I don't really understand that” or, “no, that's completely esoteric to you, and it doesn't, you know, doesn't work for me.”

Sometimes I do just push on with a thing that I really want, of course. I’m not even sure if the other guys involved in this remember this, but when there's a robot hidden in a crevice in Tölva, and it turns and talks to you and some of the stuff in the chatter is like a bit of music and 20th century radio plays. I don't know why, but I really loved that. I just knocked it up in an afternoon and when I looked at the weirdness of it. We're in this super ambient techno universe, and then there's just a bit of Spanish guitar that plays or something. It just echoes through the landscape, and everyone else was like, “oh, no, I don't like that.” It was a battle. I had to insist that that went in, in the end, just because it really, really spoke to me. I knew if it spoke to me, it would speak to others, even as others balked at it. But equally, the rest of the process is just as iterative. It's just as collaborative. It's just as about suggesting how something should be and then agreeing to compromise.

I definitely don't have a formal approach that I take to science fiction as such, aside from basically having a big bag of ideas and pulling them out and showing them to other people and seeing how they react. The other thing is that I don't really feel I know how to make games. I don't really even really regard myself as a game designer in any primary sense. I’ve kept making games on and off since I was like twelve years old with different friends and collaborators, but I still feel slightly outside it. I do level design and fill out spreadsheets full of numbers, but ultimately I'm a writer. I'm not a programmer or a 3D artist. So the stuff I contribute to this tends to be wordy and conversational. It will be part of the conversation that ends up creating the game, but every game ends up being a function of the people who made it and the conversations you have with them. Making sure that I contribute as much to that conversation as I can, and that it is faithful to the sort of obsessions that I have, and that that doesn't end up undermining what other people's kind of contribution and interest in what we're producing ends up being is the whole of my approach.

I feel that all of the Big Robot games thus far have been learning experiences. They've been experimental. Can we do this? We learned a lot doing Hunted, but it was completely unexpected and experimental and the design, the writing, the narrative, that approach of science fiction probably has that kind of speculative amateurishness for me throughout that I feel like the other games do as well. Tölva was definitely a much more mature run at things, but it was still very much sort of “how far can we push the fidelity of something that's only made by three or four people?”

If we have lots of concept art, like a proper studio, what does that mean for a tiny group of people? My relationship with Ian McQue was very much a conversation as well in the sense that he kept drawing a lot of random stuff and I connected a thread through a load of it. I remember sitting down with Ian actually and saying, “of course, you have these three distinct kind of like…” and he was like, “no, no, no, I’m just drawing random shit.” But you can divide them into the category of flying ships, Gothic stuff, and the category of slightly oppressive, rundown post-apocalypse stuff, and then space stuff. Me coming to that and dropping my categories over it wasn't necessarily any use for anyone, but it was how I had interpreted his work and probably said a bunch about my approach: looking for connections.

I feel a bit like the methodology is to just collect as much stuff as I can and be as interested in as many things that I can, and to have enough jokes that I don't seem entirely unoriginal when asked to write funny stuff. Connect as much of it as possible, without making it stiff.

Anyway, I'm sure everyone has this feeling of “oh, we're just winging it” in games. I really do feel that, even from the people who style themselves as veterans or experts, they always end up dropping some “and we just made it up” anecdote. While there are methodologies applied, and proven approaches applied, every science fiction game, any game, is something that's never been done before. I really feel that with everything that I do. I also feel like I reinvent the wheel, which is dreadful for games. It's one of the great millstones around the neck of game designers. We're constantly reinventing stuff that, actually, someone else did already. But I do it, and will continue to, I think, in everything that I produce, and so will others. But even as I do that, I think what’s important is not the effort of making and remaking, but rather remaining faithful to a whole bunch of landmarks that are receding off into my history that I can still look back at and go, “yeah, that was the thing I was excited about” (usually some science fiction image!) that I can still connect to and bring that excitement to our work in some other mode.

Transcription by Mallory Morgan

About the Author

You May Also Like