With Disney Infinity's demise, what's the future of toys-to-life?

Disney Infinity's cancellation is a huge blow to a billions-dollar video game category. What does Infinity's demise mean for the rest of the toys-to-life business?

When Activision announced in early 2011 it would be introducing a toy-game hybrid based on the Spyro franchise, the news was met with much skepticism.

Here was a new game that would incorporate long-tired property Spyro the Dragon with a business model that requires people to continually spend money on plastic figurines, on top of buying the initial software and proprietary hardware. It seemed like a model that would require a lot of commitment from an often fickle consumer.

But with $3 billion and over 250 million toys sold to date, Activision today appears remarkably prescient in its commitment to this then-unique idea that grew out of its internal game studio Toys for Bob.

After Activision showed that there was a wide market for these kinds of games, other companies hurried as fast as they could to get a piece of the category, often referred to as "toys-to-life."

Toys-to-life is fairly self-descriptive: hardware and software work together to imbue compatible physical toys with "life" within a video game. The model creates the opportunity for companies to make money from both the sale of software and the sale of a variety of toys such as figurines.

Following Activision, Disney was the next major company to make a serious push into the emerging category. Disney's interest made perfect sense: it owns some of the most-loved properties on the planet, from original Disney characters to Star Wars to Marvel (great toy material); was already in the toys business; and despite a trimming-down of internal game studios, still had Avalanche Software, an experienced game developer with a lot of talent.

All of the ingredients for success seemed to be there when Disney Infinity launched in 2013. But less than three years later, and despite crossing $1 billion in sales, Infinity last week was canned, Avalanche was closed after more than 20 years in business, and 300 people lost their jobs.

Disney's decision seemed shrewd at best, ruthless at worst.

No success big enough

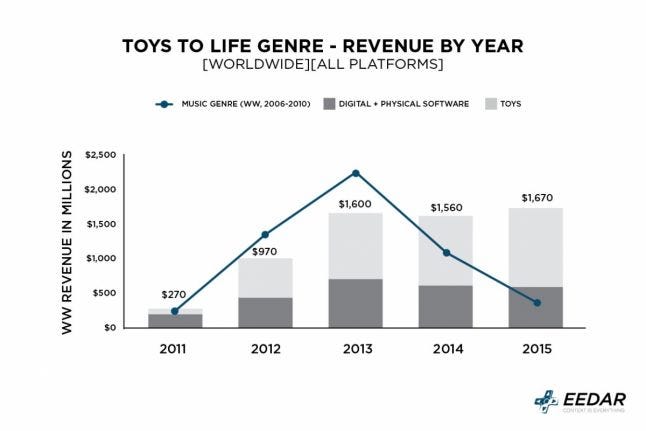

"I was shocked," said Joe Dodson, an analyst with game industry data firm EEDAR. "We've been following the toys-to-life sector very closely, because the revenue growth since 2011 has been explosive. And Disney Infinity was a huge part of that growth. It was the market leader, it had ridiculously strong licenses."

Although the signs of an ailing franchise were there (Disney Infinity revenues were sliding away and Disney was backing off from the franchise toward the end), there still seemed to be opportunity for Infinity to flourish, if only because of the resources and incredible warchest of properties possessed by Disney. Surely, Infinity could capitalize on huge marketing pushes related to Star Wars, Marvel, and Pixar films and entertainment, and print some cash.

And the fact is, Infinity was making cash. Less than a year after launch, Disney said that Infinity's global sales were $550 million, and expected to hit $1 billion. And mere months ago, one analyst estimated Disney had sold over $200 million in Disney Infinity Star Wars games and toys the previous fall.

If those estimates were correct (Disney doesn't break out its Infinity numbers), it meant that the franchise was outselling Activision's Skylanders and Warner's Lego Dimensions.

No success short of supernaturally-astronomical success could have saved the franchise or its development studio.

But for a huge media conglomerate like Disney, even that kind of success isn't enough, especially when Disney knew that a licensing model would mean higher margins and less risk than running an internally-funded effort that shoulders responsibility for marketing, distribution, toy production, physical inventory, and a 300-person game development studio.

"Disney Infinity did cash in effectively on Disney's licenses," said Dodson. "But no matter how well it did, it couldn't be more efficient than letting a third party handle logistics, and just selling the license to that party."

In that sense, Infinity was practically doomed from the start, due to the way Disney's video game business was structured. The game had become a major contender in the category, if not the market leader. No success short of supernaturally-astronomical success could have saved the franchise or its development studio. Avalanche Software was competing not just with other toys-to-life games, but against a more lucrative licensing business model.

Essentially, it was overhead that killed Disney Infinity, not a lack of success.

"We were obviously disappointed with the decision overall," said Eric Bright, sr. director of merchandising at leading game retailer GameStop, "but [it was] completely understandable, considering where Disney's focus is."

That focus, from Bright's view from retail, was again on lower-risk, higher-margin licensing deals. Disney was already lending out its properties to companies like Electronic Arts and Warner Bros. to handle the heavy lifting when it came to game production and publishing.

With the demise of Infinity, Bright sees opportunity for other major publishers' toys-to-life games to pick up the slack. In his position as head of merchandise, he made an interesting observation: Whenever a new competitor entered the toys-to-life space, GameStop saw its overall toys-to-life business grow. The different competitors didn't seem to be cannibalizing one another's sales - rather new customers were coming into the market.

But with a major player ousted from the category, there is still the risk that overall, the category could lose a large swath of its audience. "I think the challenge, and the opportunity for Activision, Warner Bros., and Nintendo will be to come in and make sure…that the toys-to-life customer of Disney Infinity [doesn't] go away," Bright said.

The bubble(?)

Whenever a new business gains explosive traction, whether it's virtual reality, peripheral-based music games or toys-to-life, skeptics - sometimes reasonably, sometimes unreasonably - apply the idea of a "bubble" that's bound to pop, sending that new business into a nosedive. With Infinity's cancellation, there has also been some chatter implying that this is the big needle pressed against a toys-to-life bubble that is about to burst. Is there a fundamental flaw in the toys-to-life business model that will cause the whole category to pop?

"No, no, not at all," Bright contended. "Our Amiibo business is on fire. We're super excited about some of the things we've seen for the upcoming Skylanders launch, and as you know, Warner Bros. has some of the best IP out there. We're still supporting toys-to-life with space in every single one of our stores, and we expect that business to continue for quite some time."

"In 2015, U.S. Amiibo retail revenues came in about 6 percent below retail revenues for Super Mario Maker, Splatoon, and Super Smash Bros. Combined."

Clumping together all "toys-to-life" games and examining them as one monolith business (…as we're doing here) is easy to do, but also tends to ignore that business models vary between franchises and companies.

For example, Disney Infinity and Skylanders share a model that requires constant, expensive game development to support the sale of toys. Developers need to make a substantial amount of game content that supports the toys, and as such, the toys and games are inextricably linked. The sale of extra hardware (e.g. Skylanders' "Portal of Power") is also required in order for people to bring their physical toys to life inside the digital game.

That's significantly different from Nintendo's Amiibo model. There are no games specifically made for Amiibos, which have sold around 64 million cards and figurines since their debut in June 2014. Games are simply compatible with them, and Amiibos are used to unlock content in games or save data. Nintendo is not responsible for making sure a studio with hundreds of workers is turning a huge profit and regularly cranking out new entire games that are based on physical toys.

On top of that, Nintendo's Wii U and 3DS have a built-in NFC reader, meaning the purchase of new hardware isn't required.

"I think the most sustainable model for toys-to-life is Nintendo's Amiibo model," said EEDAR's Dodson. "…In 2015, U.S. Amiibo retail revenues came in about 6 percent below retail revenues for Super Mario Maker, Splatoon, and Super Smash Bros. Combined."

If the method of transferring toys' data became standard and consumers were no longer required to buy extra hardware, such as all consoles employing an NFC reader, that could open up toys-to-life to a larger more diverse market, Dodson added.

Like GameStop's Bright, Dodson doesn't see doom and gloom for the category, and refutes the idea that toys-to-life will implode in such spectacular fashion as did the music genre years ago. In his data, he sees growth and stability all through 2015.

Dodson's toys-to-life analysis

A highly-complicated business

From the corporate side there is a certain amount of "move along, nothing to see here" sentiment in the wake of the cancellation of a substantial video game franchise. Disney declined to comment, and Activision only offered a canned statement reflecting suit-and-tie corporate optimism:

"We are making a phenomenal Skylanders game in 2016 that's being led by Toys For Bob, the development studio that pioneered the toys-to-life category. We've got a tremendous plan for this holiday in place and can't wait for our fans to get their hands on the newest innovation. We look forward to sharing more details soon." - Josh Taub, Senior Vice President, Product Management, Activision Publishing.

Canned corporate optimism aside, toys-to-life in the style of Infinity and Skylanders is highly complicated, and the casual market on consoles is under the gun more than ever before thanks to mobile games. With Skylanders sales slipping for the past couple of years, the next entry to the franchise does need to be as phenomenal as Activision is promising.

Skylanders has become a tentpole franchise for Activision, mentioned alongside such video game juggernauts as Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, and Destiny. Those three franchises plus Skylanders made up 71 percent of Activision's total revenues in 2015, and "a significantly higher percentage" of the company's operating income, according to the publisher. Each of those franchises in particular needs to maintain high performance.

Fortunately for Activision, the demise of Infinity could be a boon to Skylanders when it hits the market later this year, giving the franchise some needed breathing room. Activision said in a February earnings release that casual titles - specifically Skylanders SuperChargers and Guitar Hero Live - fell short of sales expectations. "We believe [the shortfall was] largely due to greater competition in the toys to life genre and due to the casual audience's shift to mobile devices," the company said in an earnings statement.

"If you look at hardware as a category beyond games, the hardware startup scene is buzzing."

While "toys-to-life" is often talked about in the context of huge publicly-held game publishers, there is opportunity for small startups to create games that implement physical and digital components, which could be encouraging news to some of the 300 Avalanche workers who've been scattered to the winds.

Alex Fleetwood, founder of indie studio Sensible Object and one of the minds behind the physical "toy"-mobile game hybrid Fabulous Beasts hopes to see some startups sprout up, bringing new ideas to the physical-digital crossover realm. He said toys-to-life (or as he calls it more generally, "connected play") can "absolutely" be a viable business, even for smaller studios.

"You know, Disney had a huge hit in this space last year - as a licensor, with the BB-8 droid," he said of the little spherical Star Wars robot that's controlled remotely via a mobile app. "That's designed and sold by a small company called Sphero that's less than five years old."

Fabulous Beasts is a game unlike the toys-to-life franchises that come out of giant video game publishers. The game utilizes a tablet, a sensor base, and many curiously-shaped "beast" game pieces that are (somewhat) stackable. As the game pieces are stacked upon each other, climbing towards their inevitable collapse, the animals appear in the digital realm, changing and evolving.

"The cost of prototyping new ideas has plummeted over the last five years, and it's rapidly becoming easier to work with manufacturers in Asia to find scale," Fleetwood said. "If you look at hardware as a category beyond games, the hardware startup scene is buzzing. Yes, there are additional costs and complexities that indies who are used to digital publishing have to get their head around, but it can't be that hard - or we wouldn't be doing it."

Between startups and stalwarts, the category that we refer to as "toys-to-life" isn't dead, but steps taken in the near-term will determine whether this is a category that's viable enough for huge companies to invest hundreds of millions of dollars. While experts say Disney's decision doesn't mean the entire category is doomed, the fact is that this is a competitive, complex market where anything can happen.

"I thought 2015 was going to be a massive year for Disney Infinity," said Dodson. "And in 2016 it's gone."

About the Author

You May Also Like