Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Design consultant Ernest Adams examines the psychological tactics used by MMO developers to generate revenue in free to play games -- and questions the ethics of games based on hate, humiliation, and powermongering.

The first job I had in the game industry was programming the PC client for suite of four online casino games collectively called RabbitJack's Casino. They ran on a small network that ultimately became America Online. The players couldn't win real money, but every day that they logged in they got 250 points to play with, and some of the good players accumulated millions of them.

RabbitJack's was a nice place. People were courteous, and there were a lot of volunteer helpers around to make sure they stayed that way. There was no such thing as "griefing." About the worst thing you could do as a player was make the other players at your table wait while you placed your bet, but since you had to bet within 12 seconds or lose your stake, it was never very bad.

The players paid $6 an hour -- ten cents a minute -- to play RabbitJack's. In retrospect I think it was the most honest business model the game industry has ever had. As long as we were entertaining people, we made money.

When they logged out, we stopped making money. People paid for exactly as much entertainment as they got, period. The price was ridiculously high by today's standards, but it was all completely straightforward.

I was pretty fired up about online games at the time. I could easily see the potential they had. The first lecture I ever gave at Game Developers Conference was called "The Problems and Promise of Online Games." The problems I listed were mostly technical ones, which we have long since solved.

At that time I didn't anticipate just how nasty online games could become, and I certainly never dreamed that game designers would start encouraging that nastiness and selling people virtual goods that let them hurt each other in real, not virtual, ways. But that's what's starting to happen.

A few weeks back a message dropped into my e-mail inbox with the subject line "An Obscenity." It was from Rich Carlson, one of the Digital Eel guys. All it contained, without further comment, was a link to the slides of a lecture given by Zhan Ye, the president of GameVision, at the Virtual Goods Conference 2009. The lecture was called, "Traditional Game Designers are From Mars, Free-to-Play Game Designers are from Venus: What US Game Designers Need to Know about Free-to-Play in China."

You can also read a report about this presentation on Gamasutra.

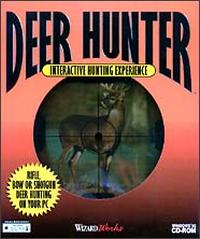

At the moment, free-to-play has the whole retail game industry in a tizzy. I saw the same thing about 13 years ago when Deer Hunter came out. A game that sold at gun shops? For $15? And was selling like ice cream in a heat wave? Deer Hunter upset the familiar business model and spawned a legion of instant imitators. The question on everybody's lips at the time was "Does Bubba really play computer games?"

At the moment, free-to-play has the whole retail game industry in a tizzy. I saw the same thing about 13 years ago when Deer Hunter came out. A game that sold at gun shops? For $15? And was selling like ice cream in a heat wave? Deer Hunter upset the familiar business model and spawned a legion of instant imitators. The question on everybody's lips at the time was "Does Bubba really play computer games?"

As we now know, Bubba does -- and so do a lot of other people we had been ignoring. Deer Hunter was the first game to demonstrate the potential of the casual market, a good ten years before we started using that term. The freak-out at the Game Developers' Conference over Deer Hunter is long forgotten, of course, but it was paralleled at this year's conference by the freak-out over Farmville and other free-to-play games.

Free-to-play is a comparatively new business model for us. Free-to-play (F2P for short) means "sort of free." The game is free if you have a lot of time, but if you want to advance at anything other than a glacial pace, you have to put money in, and that enables you to get ahead faster. Paying money also gives you an advantage over those players who don't pay.

Zhan Ye explained in his lecture that in F2P game design, every feature must be measured by two metrics: is it fun, and does it make money? The designer is no longer free to concentrate purely on creating a fun game; the designer must be a businessperson.

I ran this idea by Martha Sapeta, who's the lead designer on Sorority Life at Playdom, which makes F2P games. She told me that at Playdom, every game feature must drive one of three things:

Daily average users, which simply means "number of logins"

Re-engagement, which means number of people coming back to play again

Monetization, which means people paying money for advancement or other game features

This is a new way of thinking about game design for me. In RabbitJack's Casino, fun correlated directly with revenue. We could concentrate 100 percent on fun because that was what earned us money. Players paid for the game continuously; we didn't have to coax them to make additional expenditures.

Then I moved on to EA, where we made games sold at retail. The designer of a retail game thinks about whether features will be popular or not, but he is free to take a holistic approach to it. He doesn't have to measure moneymaking potential feature-by-feature.

The F2P business model seems a bit weird to me -- it distorts what I think of as the designer's main role -- but it's not wrong in and of itself, just different. But that's not all. Another thing that Zhan Ye said was that we have to get over conventional notions of fairness. Fairness is not a goal, just a means. In his slides, he wrote,

"The goal is to create a highly dynamic community, in which a lot of conflicts, dramas, love, and hate can happen. If it helps to create the tension -- the conflicts, the dramas -- fairness can be sacrificed. If we believe that a game world is a reflection of the real world, then the concept of fairness in the game should not be taken for granted."

So I see where part of Rich Carlson's problem is. He's an old-timer, and like a lot of old-timers, he came to video games through traditional board gaming. As a designer, fairness means a lot to him -- it's the cornerstone of multiplayer game design. And for my own part, I have never believed that a game world is a reflection of the real world -- I certainly hope it isn't.

I play games to escape, not to experience, the problems of the real world. In fact, our primary defense against censorship is the claim that game worlds are make-believe. When we blur that line, we make ourselves vulnerable. So I began to be concerned.

Then I came across this in Mr. Ye's lecture:

"The most successful F2P games (monetization-wise) in China all give their paying customers HUGE advantages. In the beginning, rich people kill poor people all the time. Balancing is a big issue. Chinese game designers tried different innovative methods over the course of last several years."

It doesn't seem to have occurred to him to create a game in which people simply can't kill each other at all -- a problem Ultima Online solved years ago when they broke the world into PvP and non-PvP shards. For that matter, nobody kills anybody in FarmVille, either. Instead, this was the solution:

"Let rich people organize family clans, hire poor people, lead them to fight with other clans, and reward them. Think about who those rich people are in the real world -- business owners and factory owners. They manage and lead hundreds of people in the real world and are used to the leadership role. In the F2P world, they still want that feeling. We just offer them that in the game, naturally.

"Clans are closely intertwined smaller communities that function as corporations. Clan leader lavishes his clan members with gifts and equipment, in exchange for loyalty and service.

"Rich people lead poor people to fight with other rich people via clans. It is much better than rich people killing poor people all the time. Creates a highly dynamic social system with better balancing."

Wonderful. This, in a nutshell, is tribalism, or warlordism. This fantasy game world they've constructed is essentially Afghanistan or Sierra Leone or Somalia, where the poor are forced into militias at gunpoint and made to fight. As game designers, we can be pleased that it creates "a highly dynamic social system with better balancing."

Maybe this is popular in China. Apparently people there will pay money for it. Perhaps when they want to escape from their day-to-day lives in an oppressive centralized regime, that's what they fantasize about: being peasants forced to fight for a brutal overlord, in an oppressive decentralized regime. But I find it appalling.

Zhan Ye defends all this in his lecture by likening it to Las Vegas. He points out that gambling takes advantage of a human weakness, but gambling never goes out of fashion; the Chinese free-to-play games take advantage of another human weakness -- the desire to dominate other people -- and that will never go out of fashion either.

Leaving aside the grotesque cynicism of pandering to the kind of people who enjoy oppressing others, I have three responses:

This is a dangerous sort of analogy. Gambling is heavily regulated precisely because it exploits weak people. Do we really want F2P to be regulated the way gambling is? In China everything is regulated, so maybe he's not aware that in the West we fight tooth and nail to maintain our freedom. I definitely don't want our legislators thinking of video games, F2P or otherwise, as anything like gambling.

The analogy is inexact. Las Vegas is not free-to-play, so it doesn't have to charge the paying players enough to make up for the money spent supporting the non-playing ones. In fact, the whole essence of the experience of gambling is that you must pay to play. Gambling is really much more like the old pay-by-the-minute online games -- with the key difference that you can win back some of the money, which is what makes it so dangerously compelling. Besides, in Las Vegas, the players do not abuse each other. The casinos make very sure that everyone behaves himself. Obnoxiousness is bad for business.

Most importantly of all, Las Vegas does not deal aces to rich players and deuces to poor ones. Rich players can play for longer before they run out of money, but everybody plays by the same rules regardless of how much money they have. The games are fair.

As if all this weren't depressing enough, Mr. Ye explains how game designers can make money out of hate and humiliation in social environments:

"Conflicts are good. Conflicts make the game world more energetic and live. More importantly, conflicts trigger emotions. When people are emotionally unstable, they are more likely to make purchases."

This reminds me of Baron's Theorem from Raph Koster's laws of online world design:

"Hate is good. This is because conflict drives the formation of social bonds and thus of communities. It is an engine that brings players closer together."

Personally I think Baron's Theorem should be called "Adolf Hitler's Theorem," because Hitler had the same insight several decades earlier. It certainly worked for him. Germany was a vibrant, diverse nation before Hitler got hold of it and welded it into a close-knit, efficient hate machine.

Even Hitler didn't use hate to sell widgets, though. Not content with fomenting conflict, the game designers Mr. Ye refers to have also invented an item they can sell to players to abuse and humiliate one another:

Even Hitler didn't use hate to sell widgets, though. Not content with fomenting conflict, the game designers Mr. Ye refers to have also invented an item they can sell to players to abuse and humiliate one another:

"[There is a] virtual item called "little trumpet," used to curse other gamers. The curse will be broadcasted to all gamers (in the same zone). A public humiliation tool. Sold a lot."

Is this what game design has come to? Creating things to sell players that enable them to be cruel to each other? Looking for opportunities to make money out of emotional instability? Bullying is not a joke, and it is not make-believe. It causes misery and pain and it can and does drive people to suicide. And I'm revolted at the idea that a game designer would promote it for profit.

Bad behavior is hardly confined to free-to-play games, of course; there are parts of Xbox Live that are plenty nasty too. But we don't have to create in-game incentives to promote it. And, incidentally, telling players to simply log off if they don't like it is not acceptable; that puts the burden on the victim. It's like telling someone who gets obscene phone calls to just get rid of their telephone.

I know online games don't have to be like this. Club Penguin isn't. FarmVille isn't. It's perfectly possible to create a Club Penguin for adults, if we want to. To be fair to Mr. Ye, he issued a disclaimer at the beginning of his lecture to the effect that doesn't endorse these practices, he merely reports them. But it's disturbing to think that the Chinese game design community regards this kind of thing as desirable. Nor is it limited to China, if Baron's "Hate is Good" Theorem is generally accepted by the MMOG community.

Avoiding hate doesn't mean we have to get rid of competition. A close, hard-fought game is a fun one. When the 49ers beat the Broncos in the closing seconds, I cheer. But that doesn't mean that I hate the Broncos or their fans. I don't have any ill-will towards the Broncos at all. If you watch American football players, they'll knock each other down with incredible violence... and then they'll help each other back up. There's no hate there so long as nobody is cheating. Boxers, fencers, and wrestlers don't hate their opponents. Hatred clouds judgment and inhibits peak performance.

There's a social convention called sportsmanship that is designed to keep competition on the right side of the line. I realize that the concept of sportsmanship sounds like something out of the 19th century; perhaps it has no place in the tough, nasty world of online gaming. But when competition turns to hatred, you have gone too far. If you are building games that foster tribalism and hatred and cruelty, you are doing evil.

There is no such thing as artificial hatred. All hate is real. And we should not be selling it.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like