Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Ex-Playdom senior designer and game industry veteran Greg Costikyan takes a hard look at free-to-play design and business practices and urges the industry to change them -- as ethical design will increase long-term value.

Long-time game industry veteran and former Playdom senior game designer Greg Costikyan offers a practical look at how ethics in free-to-play design affects a game's success.

David Ogilvy, an important figure in the evolution of the ad business, once said "The consumer is not an idiot; she is your wife." He was responding, of course, to what he viewed as cynical and manipulative advertising; but in the F2P market, we -- not all of us, but certainly most -- are equally guilty of treating our customers as idiots; or worse, as sheep to be fleeced by manipulative and fundamentally unethical business practices. Or to put it another way, we have typically emphasized short-term monetization at the expense of long-term retention, risking annoying our players in order to improve short-term metrics.

Our F2P businesses have, by nature and culture, been highly focused on the short term; startups push to get things done now, to pull in revenues now, and basically have no long-term horizon, or no longer than the three to five years before a hoped-for "exit," a sale to a larger company or an IPO. I won't name names, but I know of at least one instance in which a F2P provider purposefully set out to maximize short-term revenues from a game, knowing full well that they were burning their user base and causing the game rapidly to decline, because they were nearing a buy-out and wanted to make this quarter's revenue growth look good, to support a higher sale price.

As well, our metrics make it very easy to see what happens in the short term, and much harder to determine how things affect the long term; if you make a change to your game, A/B test it, and the metrics say your ARPDAU has increased, the tendency is to say "Great!" and close out the test in favor of your increased revenues.

But what the metrics don't tell you is that you've also done something that annoys your players and, weeks or months later, will increase your user churn; and if you see churn increasing, you will have likely made many changes in the past weeks and months, and it will be difficult or impossible to trace back to determine which changes were most responsible.

And, of course, while our businesses contain many thoughtful and ethical people, it's also unquestionably true that they contain many cynical bastards who actually believe that deploying psychological trickery to gull people into paying more is good and appropriate business practice.

As a consequence, we see, in the F2P market, exactly what you'd expect to see: F2P games typically have a lifespan of a year or less. They grow, they pull in money, the audience starts to decline, and at some point the operator concludes that life-time value (LTV) is now less that cost of user acquisition (COA), pull the plug on marketing, and the game drops into a death spiral. Existing customers churn out and few new ones enter, with the game being shuttered shortly thereafter.

For someone like me, who has been involved in online games for decades, this is astonishing. Prior to the rise of F2P, online games had the potential to live basically forever; in fact, historically it has been actively hard to kill an online game. I'll give three examples:

Hundred Years War (hyw.com) began as a computer-moderated play-by-mail in the late 1970s, became an online game on the old commercial GEnie network, and is still played on the open web today.

Gemstone (www.play.net/gs4/) began as a paid MUD on GEnie, and still exists (and makes money for) Simutronics, its developer today -- a text-only MMO still with its devoted fans.

Ultima Online (www.uo.com) was launched in 1997 -- and continues to this day, with tens of thousands of players, a now-retro 2D MMO in a next-gen world.

And let's not even talk about Meridian 59 (www.meridian59.com), launched in 1996 and shut down twice by its operators -- and still alive today, supported as a free game by its fan community.

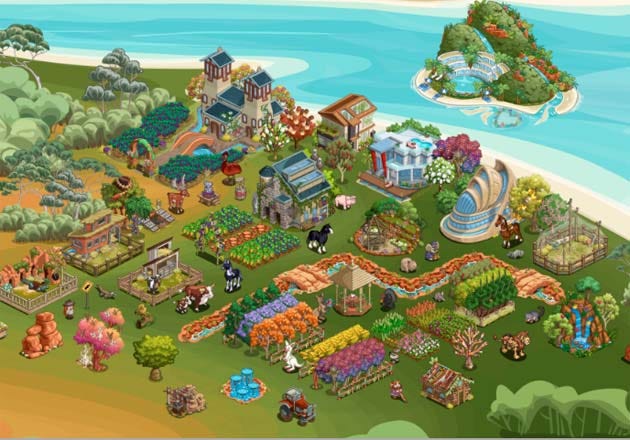

Now, you could argue that somehow the business conditions for these games are very different from the F2P market, and that it is impossible to sustain F2P games over the long term; and you would be wrong. FarmVille is the stellar example here; it still has a large and stable user base, and it still constitutes 16 percent of Zynga's total revenues, four years after its launch, and despite the launch of FarmVille 2.

At the last GDC, Mike Perry gave a talk entitled "Why Won't FarmVille Go Away?" Which it will not; neither I nor Perry see any reason it can't last for years to come, and for one simple reason: Today, although not in the past, it is managed specifically to foster player retention.

The Facebook market is, today, a mature one; there's plenty of revenue for Facebook games still, but it is not a growing market. The mobile F2P market is still growing fast, but in (at a guess) two to three years, it too will be mature. Mature markets require you to think differently: a gold rush may reward speed and short-term thinking, but a mature market rewards businesses that build customer loyalty. And treating your customers with anything other than respect is no way to do so.

Where does ethical F2P game design come into it? That should be obvious: Treat your customers with respect, and you are behaving ethically. Everything else follows from that simple principle.

The changes demanded by this shifting market will doubtless terrify many who are used to behaving in ways that seemed to work a year or two ago; but we should, in fact, welcome them. Consider: Would you rather work for a company that has loyal fans eager to play your game, or a company that assumes games are disposable trash, and players, marks to be fleeced?

Yes, I know, sometimes it's hard to respect your players, particularly after you've just watched a user test with your target demographic and marvel at how clueless they seem to be. Or look over the metrics for your first user experience, and see a big drop off when players are called upon to perform what seem like amazingly simple tasks. Particularly in casual markets, all of your players are clueless, and you need to design with that in mind; but regardless of their cluelessness, they still need to be respected. "All of our users are clueless" and "respect your players" may seem contradictory, but you need to act on both principles: You must both make your UI desperately simple, and your monetization system respectful.

As I argued above, it's often very hard to tease out the long-term impact of a change to gameplay from the short-term effects on other aspects. But in truth, common sense and a bit of intuition will get you pretty far; a gate that forces a player to either spam friends or pay money may make you a buck today, but any fool should be able to see that it will drive away players tomorrow. There's a reason Pioneer Trail failed; it pulls shockingly hard at the spam gate lever, and players quickly grew tired of it.

What else can help?

For a start, stop thinking of changes as purely things to impact your short-term metrics; think of changes as an opportunity to improve the gameplay. I'll give Dragons of Atlantis as a (bad) example here; if you look under the hood, it's pretty clear that the original designer had intended the game to foster a sense of strategy and positional warfare, but the combat system is so brutal that this never happens. You never leave troops at an outpost, because that simply leaves them vulnerable; and you almost never defend your home base (you set your troops to hide) because battles tend to result in the complete elimination of one side, and rebuilding your forces is a tiring, long-term grind. This has been true since the game launched, and despite the many updates Kabam has made, they have never bothered to fix the fact that they basically have a broken combat system -- I assume because the game is popular enough, and its producers are focused on changes that improve monetization.

If instead, they actually focused on the player experience, I think they'd realize that losing your whole army through a moment of inattention (or an attacker exploit) is a clear rage-quit moment, and that modifying combat to try to recapture the designer's original intent would likely produce a game that retains users longer. Perry, revealingly, says that one of the reasons for FarmVille's continued success is his team's work to continually add new content and features that surprise and delight its players.

I'm not saying you never make changes with a view to improving monetization; you should. But you should also be trying to make your game better purely from a game design standpoint. Any good live team should contain both a game designer as an advocate for the player, and a product manager as an advocate for monetization -- as well as a producer to determine where scarce development resources should be allocated, and serve as a moderator between the two.

We play games because they amaze and delight us -- good ones, at any rate. We still often hear that the right way to launch a F2P game is "create the minimum viable product," launch the game, and if it gets traction, invest in improving it -- with "improving it" meaning A/B testing features. To put it more brutally, this approach can be described as "throwing shit against the wall and A/B testing it until it doesn't stink."

This doesn't work, and never has; without a sound core game, no amount of tweaking will save you. And what constitutes a "minimum viable product" is subject to the same ramp up in quality over time as every other aspect of game development; the pure HTML social network RPGs that were successful in the early days of Facebook gaming would never get traction today, because we expect much more from browser games now.

Moreover, it's now true, in F2P games, as it always has been in the conventional market, that "you only get to launch once." Data shows that a game's first cohort, the first people who flock to it, monetize more effectively than later ones; and once you have lost a player, they very rarely return. You want to launch not with a "minimum viable product;" you want to launch with something amazing, because that's your best hope of snowballing a big audience and achieving long-term success. And of course, you can do geoalphas and short-term tests with small audiences to massage your FUE and your metrics before going full-bore and doubling down on your marketing spend; but you absolutely should not be launching your game broadly until you have something polished and cool.

Your players are not guinea pigs to be A/B tested; they are living human beings, and if you are in the entertainment business, it is your obligation to provide them with quality entertainment, from the very start.

We need to stop thinking in start-up mentality terms, and start putting in the extra 20 percent effort that produces polished games.

Spam Not; Message Endogenously

Time was, you heard a lot of talk in the F2P space about "K-factor." It's a term borrowed from epidemiology, actually; K-factor is the number of healthy people infected by one sick person, and in fighting an epidemic, you try to get K-factor as small as possible, by doing things like getting sick people to stay home, wear face masks, take medication, and so on. In games, we use it to refer to the number of new players recruited by each player acquired, and we want to increase K-factor. Once upon a time, Facebook games saw very appreciable K-factors, which meant that a new game could grow by leaps and bounds -- and also meant it was clearly in the interest of game developers to get players to send as many messages, and make as many newsfeed and wall posts as possible, because their visibility attracted more players.

So every game encouraged you to post virals at every turn, and in some cases pretty much coerced you to do so -- hence the "staffing" mechanic common to so many builders: to open a new building, you need six friends to agree to staff it, invite them today.

I have quit games when staffing requirements became too onerous (14 friends? you've got to be kidding); and I am sure I am not alone. They do foster messaging; they are also bad for long-term retention. And what are we planning for again?

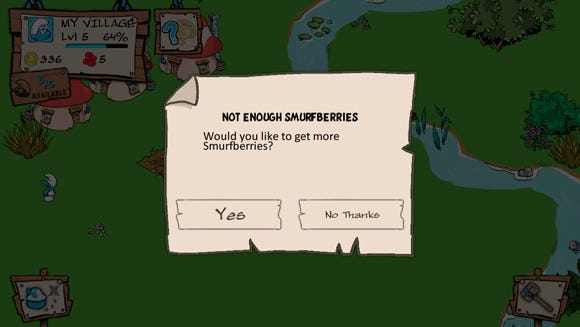

Here's an example of dishonest practice: Most games ask you to invite friends early in the first user experience. Fair enough, as far as that goes: But many also do not allow you to close the pop-up that asks you to invite. There's only a single "invite" button. The user is forced to click it -- or quit. This pops a friends-list dialog, and you can close out of that, and return to your game without sending invites; but you have just told your players "We treat you like sheep and try to trick you into sending virals." This is the opposite of respect.

A/B test your invite dialog with a close button and not, and I guarantee you will see two things: First, yes, more invites will be sent if there's no close button. And second -- you will see more drop-off at this point in your FUE, as some players say "screw you, I'm not doing that." In other words, you are trading off keeping this user against the hope of acquiring some other user; which is better in the long term is hard to say, but it is not hard to say, "You are disrespecting this user." Don't do that.

Messaging is even more problematic in mobile F2P; yes, a player can easily send messages to someone in their phonebook, or if they signed on via Facebook Connect, to FB friends. But a phone is not a social network, and this kind of messaging is even less natural than it is on a social network; few of your players will do so, unless you force them to -- and forcing them to is unethical.

The reality is that K-factor is now small, mainly because Facebook has nerfed the virals (and messages were never a main source of players in mobile). You will no longer see newsfeed or wall posts from games, except for those you already play. Typically, no more than 3 percent of your users will be acquired by virals; is it really worth annoying your players for such a small number?

Virals still are useful in terms of player retention; a player who gets a game message from a friend is more likely to return to the game, which you want, of course. But this is best fostered by positive messaging, like "free gifts," rather than negative barriers to play.

If you want to foster messaging, don't force it; instead, make it endogenous to your game, make it fall naturally and comfortably out of your design. As an example, in the (no longer extant) game, Knighthood, you played as a medieval nobleman. If you invited a friend and they joined the game, they began as your vassal -- and you received a small portion of the resources they generated each day. This perfectly suited the core fantasy of the game, and provided a strong incentive to send invites; it also served a useful purpose in terms of gameplay, because you wanted to keep your vassals happy lest they leave you for another lord, and therefore had a strong incentive to help them out. Good social engineering as well as good design, in other words.

Stop asking "What would Zynga do?" We know what Zynga would do, and it hasn't worked out so well for them. Instead, start asking "How can I get my players to want to send messages? How can I make doing so a positive experience for them? How can I build messaging into the core of the game, make it natural, make it emerge spontaneously from play?"

League of Legends is currently one of the most successful F2P games on the market. As with most F2P games, it has a number of different monetization points, but among its most lucrative is the purchase of champions. It's a DOTA-style game, and champions are playable characters, each with its own advantages and disadvantages; playing each one is a different experience, they combine with others in interesting combined-arms ways, and there's always a desire to unlock more.

While the currency used to purchase them can be ground for, it would take an enormously long time to unlock all (and to unlock the "runes" used to further customize champions -- which are only available for soft currency, and the main sink for such). Consequently, there's a strong incentive to pay, at least at times, and many players do.

This is a perfectly honest, and reasonable system; I know what I am getting, and I can see the value. Moreover, if I'm content with playing just one or a handful of champions, I can reasonably get all the runes I want for them without paying; it's only if I become very attached to the game that I'm likely to pay, and if I am enjoying it that much, I presumably feel I'm getting value for the money. (I'm not claiming LoL's monetization practices are wholly ethical, by the way; sale of rune sheets strikes me as pretty skeevy; but selling champions is pretty reasonable.)

As another example, Plague, Inc. provides seven playable disease types (for free, in the Android version, or for a buck with iOS), unlockable through play. The impatient can pay to unlock them early; but in addition, there are three additional content packs you can buy, two unlocking diseases that work very differently from the original seven, and the third providing fourteen additional scenarios. Again, an honest transaction, and I have paid for all three packs, and gladly, since I love the game and actively like giving a little money to its developers.

Content, of course, requires development time and money; it is not as lucratively monetizable as consumables or gates. It probably can't be your only point of monetization; but it is something your players will feel far more willing to pay for than a one-time bypass for a timer. I guarantee you will see a higher percentage of paying players (though not necessarily higher revenues per paying player) if you provide content for pay.

Not long ago, Wargaming.net announced that they were removing "pay to win" elements from World of Tanks. This was almost certainly a smart move; the feeling that a game is pay-to-win is a key driver of rage-quit moments, when players decide to leave because the game is pissing them off; if you're a free player, or one on a budget, it feels hateful if people are beating you just because they have more money than sense.

Clash of Clans handles this in a clever way; as in many games, you can speed your progress through the game by paying to bypass timers, but when it comes time for a battle, you are always matched against a player of roughly equivalent power (based on town center level). If I have a level 6 town center, I will be matched against a player within a couple of levels of mine -- and it doesn't matter whether they got there by grinding or paying, it will still be a fair battle. Paying advances you quicker, but it doesn't give you an advantage when the battle begins.

A friend who played CityVille once told me "I paid $50 -- and it's gone." In other words, he liked the game, and was willing to pay -- but afterwards, regretted it. He didn't feel as though he'd gotten value for money. And soon afterward, he was gone, too; he quit the game.

Clash of Clans is one of the few games to have monetized me. It gates the number of buildings you can have under construction at one time with "builder huts." You start with one, and purchase another with hard currency (a forced purchase) in the first user experience. You see the value at once; more huts means a permanent, secular, continuing speed up in your ability to progress. Additional huts cost hard currency, and you can grind for hard currency by completing achievements; interestingly, the achievement rewards are rich enough that you can build a third and a fourth hut by grinding (though the fourth hut won't come in until the elder game, by which time you are more likely to be resource constrained than held up by too few builders). But for $10, you can buy a third hut immediately and have enough hard currency left over that a handful of days' grind will get you a fourth. That's pretty reasonable, by the standards of F2P. I liked the game, and was willing to do that. (Paying to bypass timers, not so much, but then, I'm no whale.)

I appreciated that I had the choice: That I could grind, if I preferred. It felt like an honest and reasonable transaction. Interestingly, Backyard Monsters: Unleashed, a similar game, makes your third builder a real-money transaction, and doesn't let you grind; I'd be interested in knowing whether this works better or less well. It's still an honest offer, but CoC's willingness to let me grind made me like the game more; Supercell knows how to monetize, but it pulls gently on the levers. (Well, at least until the elder game, when the slow production rate of dark elixir provides another strong temptation to spend.)

Similarly, League of Legends lets players play some champions for free each week, on a rotating basis. This exposes players to different champions and their advantages and disadvantages; players actively like the opportunity to experiment with them. This undoubtedly leads to additional sales, when a champion is no longer free to play; players who enjoyed that champion's play style will be motivated to purchase it. Try before you buy, in other words; but in a way that players find positive and unobjectionable.

Many have decried the level of grind in F2P games, but this isn't a characteristic of the business model; rather, it follows from the fact that virtually all F2P games are "games neverending," like MMOs. That is, they do not come to an end and have no winners or losers. In a game neverending, you need to spin out gameplay as long as possible, because you have limited content, and even in the best case, your players will consume your content more rapidly than you expect. That's why timers lengthen in the mid-to-late game in games that have them; that's why leveling in WoW requires grinding through mob battles.

Grind is not ideal from a game design perspective; but it's pretty much a necessity for games neverending. (Which is a reason why I'd love to experiment with F2P games that do come to periodic conclusions, but that's another story.)

And it's acceptable to allow players to speed up or bypass the grind for purchase; what isn't acceptable is make progress either impossible or insanely difficult without paying. Some levels in Candy Crush, for instance, are (seemingly) purposefully designed to require dozens or even hundreds of attempts to get past unless you pay for additional moves or powerups.

Interestingly, King seems to have nerfed some of these levels over time; I have no doubt they responded to player complaints, but also that they A/B tested the change. So I think we can posit that, yes, pulling on the monetary levers more gently has been successful in increasing their long-term customer value; better to keep them playing with the hope of monetization in future than cause them to rage-quit.

Of course "insanely difficult" is a fuzzy phrase; but the point is that you've made a promise to players that they can play, and grind, without paying, if they so chose; you have to keep that promise, and that means more than just "you have a tiny chance of being able to progress."

Marvel Avengers Alliance has monthly "spec ops" releases. A spec op is a series of linked battles (with a story arc attached); players who complete the series within a set period of time, usually a couple of weeks, get a new playable superhero for free.

However, each of the battles in the spec op requires expenditure of a currency available only for the duration of the spec op (called "unstable ISO"). Each time you initiate a battle in the series, you expend some of it. Players are seeded with a certain amount, but not nearly enough to complete the sequence.

Players can gift each other unstable ISO, but the amount a player can receive per day is strictly limited; and unstable ISO can also drop as a reward during a battle. In short, the developers can constrain the amount of unstable ISO a player can earn by adjusting the "receivable per day" parameter, and the drop rate in battles.

There are intermediate rewards over the course of the spec op; that is, at some point in the mission sequence, a player will be rewarded with a rare weapon, or a small quantity of hard currency, or something else of value. Players of the game actively like spec ops, because they provide new, periodic content, there's a tasty reward at the end of the sequence, and even if they are unable to complete it, they can receive the intermediate rewards.

Needless to say, unstable ISO can also be purchased for real money. And since the superheroes rewarded by a spec op are later put up for hard currency purchase, it is possible that, by purchasing a limited quantity of unstable ISO, you may be able to obtain the superhero for less than the outright purchase cost.

Is this system unethical? I would argue that it depends. If the game's parameters are tuned so that, with optimal play (maxing daily unstable ISO gift reception, losing few to no battles, spending the time to grind), a player can complete the series, then it strikes me as ethical: You're giving players more content, and non-payers can still succeed, though they have to work at it.

If, however, the parameters are tuned so that players literally cannot complete the sequence without paying, then it strikes me as unethical. It's a bait and switch; it's like Lucy pulling the football away from Charlie Brown. You're holding out a reward and giving players the impression that they can get there by grinding, but denying them that opportunity. Players will wise up to this, eventually -- and you will lose some who do.

We need to relearn the dark arts of customer service and relationship management. MMO developers know this well; they know how important the forums are, how fans can serve as ambassadors for the game, how what gets said on the forum can raise warning flags early when updates cause problems, how sometimes some of your best ideas can come from your players. Yes, it's true that this kind of information is anecdotal, while your metrics are hard data; that players sometimes don't really know what they want; that players often misidentify a problem (e.g., they say something is "too hard" when really it's too boring); and that quite often you can't do as they wish, because market conditions don't permit it. Of course you keep analyzing your metrics, too.

In the F2P space, by contrast, customer service has been treated as a cost sink, something to be ignored or minimized; many games make it actively hard to find anyone to help when you have a problem. Even when there is a customer service function in the organization, it often is isolated from live teams, with only a trickle of information back from CS to the developers -- and almost never any information from the dev team to players in advance of updates. This is no way to foster a community.

Customer service is not a cost sink; customer service is an opportunity to retain players you might otherwise lose -- and given how much money you spend acquiring players, retaining them is valuable. A customer in hand is worth two in the bush.

The F2P market has been dinged on the fact that most games rely on whales, a small proportion of the audience who spends disproportionately. This raises no ethical issues if your whales are princes from Saudi Arabia or tech-boom millionaires; it is an issue if someone living in a trailer park is spending $5000 they can't afford.

Why not be super-ethical?

The third time within a month that someone makes a real money purchase, pop a dialog saying, "We appreciate your business, and are very glad you want to spend more on our game. But you've already spend $XXX this month. Are you sure you want to spend another $XX?"

Likely with a checkbox saying "I'm fabulously wealthy, don't bother me with this again."

Yep, you'll likely make less money. But you'll build good will. And maybe you'll sleep better at night.

In a retail environment, transactions are simple. If you wish to play Call of Duty, you must pay to purchase it -- but the revenues of its publisher are capped at the standard retail price.

F2P is different. You can use psychological techniques and ethically dubious tricks to slide bills out of your customers' wallets -- or you can get them to want to pay you. And either way, your per-customer revenues are capped only by their willingness to pay.

Isn't it better if they are truly willing to pay?

Why would someone want to pay you?

Because you've shown them the value; they can see that this purchase will provide access to new content, or give them capabilities they don't currently have, or let them advance more quickly. They understand the transaction, and find it worthwhile.

Because you've provided them with an amazing and delightful experience, and they don't mind giving you a little money to support you and your future efforts.

Because you're responsive, respectful, and creative in your interaction with the community; they know you to be good guys who love games as much as they do. You are not cynical vultures tricking them into something dubious; you want to provide value for money, and to ensure that they are happy with the exchange.

Because they anticipate and hope for even more amazing developments in the game -- developments you've primed them for on the forums and in your messaging -- and know that paying helps ensure the game will continue and grow into the future.

Because they like you, and have the sense that you like them.

That is ethical F2P game design; that's what will ensure that your players stick around; that's the smart way to approach a mature market; and that's what will make your game last, potentially forever.

There's a genre called 4X: that stands for "explore, expand, exploit, and exterminate." Too often, we concentrate on "exploit and exterminate." Let's focus more on "explore and expand."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like