Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this extract from Morgan Ramsay's Gamers at Work, which explores the challenges of starting and building developers and publishers of video games with 18 of the industry's most successful entrepreneurs, Gamasutra presents a conversation with Tony Goodman about the history of Ensemble Studios, creators of the Age of Empires series for Microsoft. The book also includes discussions with Warren Spector, Jason Rubin, and more.

April 23, 2012

Author: by Morgan Ramsay

[In this extract from Morgan Ramsay's Gamers at Work, which explores the challenges of starting and building developers and publishers of video games with 18 of the industry's most successful entrepreneurs, Gamasutra presents a conversation with Tony Goodman about the history of Ensemble Studios, creators of the Age of Empires series for Microsoft. The book also includes discussions with Warren Spector, Jason Rubin, and more.]

In 1991, Tony Goodman cofounded Ensemble Corporation, an information technology company, with longtime friends John Boog-Scott, John Calhoun, and Thad Chapman. The company later made the Inc. 500 and was recognized as one of America's fastest-growing companies. Ensemble Corporation was acquired by USWeb Corporation in 1997.

Two years before, Goodman cofounded Ensemble Studios with John Boog-Scott and his brother Rick Goodman. With the introduction of the Age of Empires series, Ensemble Studios became the leading developer of real-time strategy games. Microsoft acquired the company in 2001. Age of Empires became the bestselling strategy game franchise of all time.

But as Microsoft's Xbox business was growing, the Windows game business slowed. During the development of Xbox 360's Halo Wars, which also became a bestselling title, Microsoft enacted plans to close Ensemble Studios and lay off all of the employees. By January 2009, Ensemble Studios was reduced to the pages of history.

Ensemble Studios left behind a tradition of entrepreneurship. Goodman founded Robot Entertainment the next month. Several startups arose from the ashes, spearheaded by former employees, including Bonfire Studios, Newtoy, Windstorm Studios, Pixelocity, Fuzzy Cube, and GRL Games.

You started Ensemble Studios in 1995, two years before the USWeb acquisition. Why video games?

Tony Goodman: I've always loved computer games and had been keeping an interested eye on the game industry. At that time, PC games were about to undergo an important change: from running on DOS to running on Windows. I saw an opportunity in this.

Up until 1995, creating computer games required an onerous investment in writing hardware drivers. There were no standards for DOS peripherals, so game developers had to write their own mouse and sound drivers. To make a game stable, developers would have to write and test special code for every different mouse and sound card available. Since new products were always being released, developers had to continually update and rerelease their game's mouse and sound drivers. It was a technical nightmare, and none of this code had anything to do with making games. Developers had to do all this in addition to creating great games that were better than the competition.

This was a significant barrier to entering the video game market, but Windows-based games were about to change all of that. The Windows operating system was quite sophisticated when compared to DOS. Windows handled all hardware at the OS level, so game developers would no longer have to develop drivers. That meant that developers could now devote 100 percent of their efforts toward making great gameplay.

It also meant that legacy game developers would lose any advantage that they had gained from their years of investment in hardware drivers. That was going to level the playing field! It was at that moment that I felt the industry was about to explode, and it was time to jump in.

In the midst of all your success, why did you pursue something so vastly different from enterprise software?

TG: I loved the business of developing software, but I wanted to create products that everyone would tell their friends about. I wanted to create a pop-culture phenomenon. If you want to create software that people really want, developing video games places you at the center of the universe.

TG: I loved the business of developing software, but I wanted to create products that everyone would tell their friends about. I wanted to create a pop-culture phenomenon. If you want to create software that people really want, developing video games places you at the center of the universe.

Creating video games seemed like a crazy change of direction to my friends, but to me, it was inevitable. I could have continued to pursue the business that I had been successful in, but I realized that you don't create passion by pursuing success. You create success by pursuing your passion. After years of developing business software, I decided it was time to finally pursue my original passion: video games.

While I maintained my management responsibilities as president and chief executive officer at Ensemble Corporation, I developed a plan for a new venture. Angelo Laudon, one of my key programmers, was also obsessed with games. We would talk about games until the early hours of the morning.

In 1995, Angelo and I began to develop a prototype engine that could be used to produce multiple games. Once we began developing the engine, there was no going back. My exhilaration for games could no longer be contained. The floodgates were opened. We were creating something special and could feel it.

How far along was the company at that point?

TG: Early in 1995, while still a part of Ensemble Corporation, Angelo and I began experimenting with graphics code in the new WinG library, the technology from Microsoft that would make games possible under Windows. We began formulating our ideas about creating a historical strategy game, inspired by Sid Meier's Civilization.

Our greatest need at that time was to hire our first artist. I looked over dozens of resumes and interviewed 13 candidates. Finally, I decided on an artist who I thought was really talented. I offered him the job, and he happily accepted.

The next day, I got a call from a young man, fresh out of art school. Brad Crow seemed very eager to interview. I told him the position was filled, but he came in to speak with me anyway. Within 15 minutes, I thought, "Holy crap, this guy is amazing." I knew that I had hired the wrong guy, so I offered Brad a job on the spot. I called the first artist and made my first ever "job offer retraction". It was an unpleasant thing to do, but you can't afford to make any compromises with early employees in a startup.

By the end of the year, we had a working version of Age of Empires that we were calling "Dawn of Man." The gameplay was in the early stages of development, but it looked remarkably similar to the final product. Units could run around the screen, fight, and chop wood. It was a sophisticated sandbox. We had a fantastic level designer and a first cut of rudimentary gameplay. But we hadn't figured out whether the game was going to be a strategy game like Command & Conquer, a simulation game like SimCity, or a turn-based game like Civilization.

I had remained in contact with a longtime friend, Bruce Shelley, who had previously assisted Sid Meier with the design of Civilization and Railroad Tycoon. My brother Rick and I had met Bruce Shelley at a board game club at the University of Virginia, where Bruce was attending graduate school. I was young at the time, but had remained friends with Bruce. Bruce had a quiet yet professional presence as a designer in the game industry. Later, he came aboard as the official spokesperson for the Age of Empires franchise.

As our prototype really started taking shape, we decided to incorporate. I incorporated Ensemble Studios in February 1996 with John Boog-Scott and Rick as cofounders. Rick took on the role as lead designer and project manager. I served as CEO and art director. John and I together headed both corporations.

We remained within the offices of Ensemble Corporation and shared expenses with them. We hired six people to start: a few programmers and three artists. Angelo Laudon and Tim Dean were Ensemble Studios' first programmers; and Brad Crow, Scott Winsett, and Thonny Namuonglo just graduated from the Art Institute of Dallas. Brian Sullivan came shortly thereafter to help with the design, implementation, and management. That was the beginning.

Many startups bootstrap and reinvest earnings to build their organizations, but you did things very differently with Ensemble Studios. How did that impact the company's ability to move forward?

TG: Ensemble Studios began as a pet project of mine while I was running my first company. I originally did this to mitigate risk, but it turned out to be absolutely critical to our early success. Before the days of digital distribution, the only way to sell your game was through the major retail chains. Those stores only purchased games from the big software publishers, such as Microsoft, Electronic Arts, and Activision. This meant that you had to negotiate a deal with one of the big publishers.

However, a common tactic of publishers was to drag out negotiations until developers ran out of money. Sooner or later, a developer would have to sign a deal just to keep the company afloat. A deal signed under those circumstances will result in very unfavorable terms. The big publishers knew they had game developers over a barrel.

The only way to successfully negotiate with a publisher was to have enough money to last as long as the negotiation might last, which could be anywhere from two months to two years. Having the financial backing of my first company afforded us the ability to negotiate with publishers on our own terms.

We didn't have to take the first deal that publishers offered. We were determined to beat them at their waiting game. Eventually, Microsoft tired of negotiating and gave us the deal that we wanted. This deal, in turn, laid the groundwork for the next decade of deals we did with them.

What other publishing options did you consider?

TG: I briefly considered self-publishing Age of Empires. Self-publishing enterprise software had taught me valuable lessons about the advantages and disadvantages of publishing. In order for our game to be as successful as I wanted it to be, we needed to have world-class software distribution. That is why, in the end, we chose Microsoft. They were the world's largest seller of consumer software with incredible distribution muscle.

Microsoft had distribution channels established in Germany, France, Spain, Asia, South America, and Japan. In the United States, they had strong relationships with American retailers, such as Best Buy, Toys R Us, and Walmart. No one could put together a marketing campaign as strong as Microsoft could when they were motivated to do so.

Self-publishing is a good option for those who want to create a very small yet highly profitable business inside the United States. But I didn't want to create just a successful game. I wanted to create a worldwide phenomenon. I wanted everyone who had Microsoft Windows to buy Age of Empires. For that we needed the global power that only Microsoft could provide.

What else did you need? Did you have a strategy for creating a phenomenon? Is there a formula for a successful franchise?

TG: To create a phenomenon, I had to do three things. I needed to convince my employees they would create the most amazing game ever made. I needed to convince Microsoft that Age of Empires would be the most amazing game they've ever sold. And I needed to convince the world Age of Empires would be the most amazing game they've ever played.

TG: To create a phenomenon, I had to do three things. I needed to convince my employees they would create the most amazing game ever made. I needed to convince Microsoft that Age of Empires would be the most amazing game they've ever sold. And I needed to convince the world Age of Empires would be the most amazing game they've ever played.

So, first, putting together this core team was the most important step in the process. This was my first game, so I got to hire each team member with love and painstaking care. I asked esoteric questions like, "What are your life's dreams and goals?"

I sought seekers. I looked for brilliant young programmers and artists who wanted to pursue a grand vision. I hired dreamers who believed they could change the world. Each member had to be both a follower and a leader. I needed followers who were naturally attracted to my grand and crazy leadership style. They were also the future leaders who'd be teaching, by example, new employees to do the same.

As the initial team came together, I settled on the high-level vision for a product that I believed would capture the imagination of gamers.

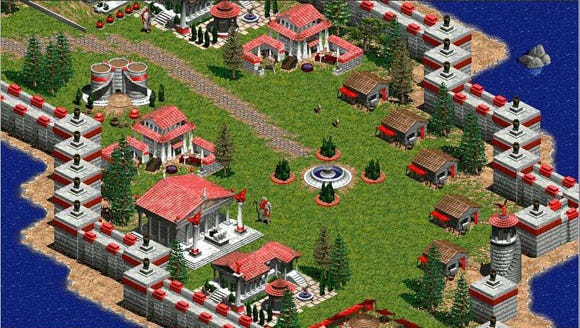

The idea was that you would get to play a game that looked like the epic Greek, Roman, and Egyptian war movies, such as Spartacus and Alexander the Great. From a bird's-eye view, the players would get to build the Great Pyramids or command realistic armies through exotic locations while building their own empire.

This vision was the perfect high-level goal for the team I hired. They got it immediately. They didn't require a lot more detail to be inspired into action. At this point, forward progress took on a life of its own. That's not to say the process was easy. It was almost never easy. But even in the hardest times, we were riding a relentless tidal wave of momentum.

Second, at this point in time, Microsoft was having difficulty breaking into the game market. They had a few respectable products, but they had no real hits. I needed to convince Microsoft that Age of Empires would be the game that would make them a major player in the video game industry. I knew that once they believed this, they would throw all their global resources behind it, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. Microsoft may not have the most creative marketing, but when they are organized and determined, they are unstoppable.

Bill Gates was instrumental in solidifying Microsoft's support for Age of Empires. Microsoft was already very eager to have their first blockbuster game. Many Microsoft execs were happy to jump aboard with our product, but some, including Bill Gates, had reservations. Eventually though, opinions unified when Gates declared, "This is a product that we will do everything we can to make a classic, like Flight Simulator, so the popularity goes on and on."

The main concern about Age of Empires was the game's depth. Some were worried that Age of Empires was too complex to become a mainstream hit. Gates' commitment paid off. He stated, "Age of Empires is an amazing product. It is so deep that I wondered if the mass market would get into it, but they did in a big way."

And, finally, magazines like to report massive blockbusters or colossal failures. Everything in between is not news. I don't like leaving marketing and public relations to chance, so while Microsoft was doing their public relations campaign, I did mine. The key was to get a "first follower" -- a well-known opinion leader who is an early advocate of your product.

I built relationships with the most recognized game magazines. Microsoft had dozens of public relations specialists, but the press prefers to speak with the game creators, not software publishers. I invested a lot of time with key editors, seeding the idea that Age of Empires would be "revolutionary" and would become a "phenomenon." They may not have believed me at first, but my goal wasn't to convince them. My goal was to plant wondrous possibilities in their brains and create anticipation, like Christmas for kids.

When the first early previews began appearing, they were using the terms that we seeded: "revolutionary" and "phenomenal." These early opinions were then picked up and echoed by other publications, creating a snowball effect. Eventually, all the publications would get on board with this message just so they didn't look out of touch.

How critical were expansions, bundles, and player-created content? Were these elements part of your vision?

TG: To design a successful game, I think about three basic pillars: deliver fantastic gameplay, create a unique graphical look, and fill a void in the marketplace. Age of Empires was the first historical real-time strategy game on the market. Microsoft was convinced, based on a previous experience, that expansion packs never make money, so they weren't interested in doing them. So, that wasn't part of the original plan.

When Age of Empires blew away Microsoft's sales forecasts, we convinced them to publish Rise of Rome, our first expansion pack. That expansion pack was the most profitable game that Microsoft had ever published. Microsoft was then convinced that expansion packs were the best way to make money.

Player-created content was always part of the strategy, although we never attempted to monetize it. We wanted player-created content to be an extra value that our customers got for free.

How did you get in touch with Microsoft in the first place?

TG: I first approached Stuart Molder at Microsoft during the 1995 Game Developers Conference. He was giving a talk on publishing games with Microsoft. As he finished his talk, Stuart was mobbed by hopeful game developers who were anxious to show off their game demos.

They were hoping for a break that would land them a major publishing deal with Microsoft. The scene reminded me of sports fans jockeying for an autograph from a revered superstar. I could tell it wasn't the best way to rope a bull.

I decided to sit in the back of the room and act disinterested. I never looked up until the mob had dissipated and Stuart was packing up his materials. On my way out, I casually told him that I headed up a game company that included some legends like Bruce Shelley, co-designer of Civilization. This was my ticket to further conversation, as Stuart had appeared on a television show with Bruce. I told him we were working on something big, and I would be happy to let him know when we were ready to demo it. We exchanged business cards, and I departed, hoping that I had made a memorable impression.

Six months later, I called Stuart and left a message that we were ready to show our game. Microsoft had a team down in Dallas within the week. Microsoft was still new to the video game business and was struggling to be taken seriously by gamers. They had not yet made a hit game. They were actively looking for a gem that could plant them firmly in the center of the computer game business. Microsoft was wowed by our demo, and Ensemble Studios was on the dance floor.

It's a validating feeling to be wooed by Microsoft. They are great at giving you attention when they want something. They threw some really crazy parties. On one occasion, they threw a Roman toga party. The entire San Jose basketball arena was commandeered for this soiree. It was the most lavish party that I've been to. Everyone was required to wear a toga supplied by Microsoft. This party featured a table piled high with turkey legs, giant goblets of wine, and female models posing as white statues standing atop columns of marble. There were wild animals, gladiators, slaves, games, fortunetellers, fire jugglers, and more wine. All this was led by the Caesar of ceremonies, Alex St. John.

The most memorable event was when a fully-grown 400-pound lion escaped from its cage and walked the floor freely amid hundreds of drunken, dumbfounded guests carrying turkey legs. Major catastrophe was avoided as the lion was shooed back to his cage without incident. I never saw another giant man-eating cat at a Microsoft party again.

While getting Microsoft to the table was an easy task, negotiations were a long, drawn-out process. We shopped the game to multiple publishers, including Hasbro Interactive, Electronic Arts, and 7th Level. When negotiating with Microsoft, it's important to play the field. Microsoft negotiates hard. They don't respect you unless you do the same. I could write chapters just on negotiating with Microsoft. However, one important rule is "do not get into the ring with Microsoft unless you're prepared to go the distance. If the negotiation takes under six months, you got a bad deal."

Age of Empires

Negotiations are often about compromise. Was this your experience with Microsoft? Did you ultimately get a fair deal?

TG: Negotiation is often about compromise; however, negotiating with Microsoft is more often about leverage. In my years of negotiating with them, I didn't often see them give in on any points they didn't have to, and I learned not to give in on any. I learned that when negotiating with Microsoft, you will only get what you ratchet away from them. With other companies, I've experienced willingness to compromise. It's just not Microsoft's style, though. I felt that we always got a fair deal with Microsoft, but it was always a lot of work.

Can you give me any examples of the sort of things that Ensemble and Microsoft haggled about?

TG: Money was the main issue -- royalty rates versus the development advance. The greater the cost that the developer is willing to pay for on the front end of the project, the higher the royalty rate the developer deserves on the back end. We would have liked to have retained the intellectual property rights to Age of Empires, but since this was our first game and we had no track record, I didn't think we had the leverage to swing it. I also wanted control over marketing, but we never saw eye-to-eye on that point.

Was a sequel or trilogy part of the deal?

TG: No, we were a little naïve at this point. Our first sequel proposal included eight games over four years. This was crazy, but Microsoft was drinking the same Kool-Aid that we were, and they thought it was a great proposal. I'm sure glad that we didn't sign the deal, because we would go on to average two years per game. We would have been locked up for 16 years.

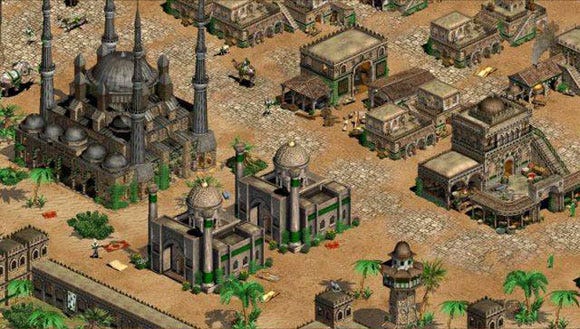

I did know that the next Age of Empires game would be a medieval game, but that game wasn't negotiated until long after the first Age of Empires shipped. Six months into the development of Age of Empires II, we still had not finalized the deal terms with Microsoft. To compel Microsoft to compromise on terms, we made a difficult decision to stop work on the project, which jeopardized the holiday ship date.

When Microsoft sent their production team down to Dallas to see the latest progress, they found the entire company playing ping-pong, billiards, video games, and board games. We were doing anything but working on Age of Empires. That caused something to happen up at Microsoft, because within a week, we had finalized the deal terms that we had been negotiating for six months.

The third Age of Empires topic was the most controversial. Some of us wanted to do the colonial time frame, and some of us wanted to move straight into World War I and II. It was the subject of heated debate within Ensemble. Microsoft was very happy to keep their distance from this topic, so they left the issue to us.

How was working with Stuart Molder?

TG: Stuart was great to work with. He was a true believer in our game and our development team. He stuck behind us, and ultimately convinced Microsoft to bet the farm on Age of Empires.

This turned out to be a game changer for Microsoft. Age of Empires was first of the two monumentally successful franchises that gave rise to Microsoft as a worldwide video game powerhouse.

For several years, Age of Empires was responsible for as much as 50 percent of Microsoft's game revenue. In 2001, Bungie's Halo would launch Microsoft to even greater heights, leading to their dominance in console games.

Although we relinquished the Age of Empires intellectual property to Microsoft in our first deal, we were still able to maintain significant negotiating leverage for future versions of the game. This was due to the technical complexity of our game. It would be extremely difficult for another developer to faithfully reproduce our gameplay experience. This ultimately led Microsoft to acquire us in 2001.

What do you mean by "technical complexity"? What would make reproducing the gameplay experience difficult?

TG: We built our own proprietary engine, and there were many components that were very difficult to reproduce. One extremely complex part was our pathing algorithms. When you click on a unit and it needs to move somewhere, it must find the most efficient path from point A to point B. When scores of units are moving at once, each unit's moves can block or unblock potential pathways for any other unit. We literally had hundreds of units moving all at once, and all of them were potentially affecting every other unit. As a result, the routine became extremely complex.

Another very difficult problem was computer synchronization. You can have up to eight players in a game, and each player might have 50 or more units move around at once, yet all eight computers needed to stay perfectly synchronized. This needed to happen 30 times a second. That was an exceedingly difficult network programming challenge. Age of Empires I was even more difficult because we supported this over dial-up connections.

Tell me about the Microsoft acquisition in 2001. Did you approach them about selling?

TG: Shortly after the release of Age of Empires I in 1997, Microsoft approached me on numerous occasions and expressed interest in Ensemble Studios joining the Microsoft family. They made a few lowball offers, but we didn't enter serious discussions until we released Age of Empires II in 2000.

When I founded Ensemble Studios, I resolved to not sell for under $100 million. That resolution may have been more of an aspiration than a calculation, but it became an invaluable metric around which I managed Ensemble Studios.

Age of Empires II

How did you determine that figure?

TG: Your company is worth only what you can convince someone to pay. To do this favorably, you must address three factors: revenue, which determines a minimum value; potential, which determines a maximum value; and time. To close the sale, you need to create a vanishing window of opportunity.

Revenue is determined by financial data. A company is minimally worth some multiple of its profitability. Age of Empires II was on its way to becoming the bestselling PC game of all time, so our financial health was outstanding.

Potential is determined by strategic synergy. A company's maximum worth is the benefit it brings to the acquirer. Prior to Age of Empires I, Microsoft had not built a reputation as a top-tier game company. To obtain a premium value for Ensemble, I had to convince Microsoft that purchasing Ensemble Studios would redefine their image in the world of video games.

And to control the sale, you need to control the timing. Cash-rich companies can afford to take their time. They will always hold out for a better price if nothing motivates them to close. To create a deadline, I had decided to work with a new publisher for our next game. This gave Microsoft two options: buy our company or compete with us.

Why did you sell? Was Ensemble not doing well?

TG: Ensemble was doing fantastic. The best way to leverage success is with a powerful strategic partner, like Microsoft, who benefited from the deal. We were the perfect match at that time.

There are typically two types of sale: fire sales and strategic acquisitions. The first type, a fire sale, occurs when a financially troubled company is willing to sell for cheap in order to avoid bankruptcy. The second type, a strategic acquisition, is a premium-priced sale that occurs when the acquirer needs something that the acquired has in order to complete some larger strategy. Our purchase was strategic for Microsoft at the time, as they needed us to take them to the next level as a game publisher.

We determined that there was an excellent fit between us and that we both benefited from the acquisition. Then we engaged in a lot of negotiation regarding long-term commitments, strategic plans, franchise direction, control, and key people. In the end, it all came down to the sale price. I had to draw a line in the sand. Finally, many months after negotiations had started, Ed Fries and I agreed upon a final acquisition price during dinner at the Third Floor Fish Café in Redmond, overlooking Lake Washington.

That said, I've always had a passion for games, but even more so was my desire to build something great and enduring. It was a tough call to sell Ensemble. The company was my prized possession, and I had a deep attachment to the family I had built. I nurtured the employees, giving them opportunitiesthat they wouldn't have had otherwise. I wanted to enrich my own life by enriching the lives of my employees.

My philosophy at that time was to give out stock options to align the goals of employees and management. Too many times have I seen companies whose owners make a lot of money and the employees get nothing. In those cases, selling is only good for the owners. So, I had created a stock option plan where all of the employees benefited from a successful acquisition. That aligned everyone's long-term goals. I knew that it was time, and I felt that I had achieved that success.

How did you feel about losing ownership of an organization in which you invested a great amount of time and resources?

TG: No one likes losing ownership of something like that. Parents don't like seeing their children go off to college, but it is a necessary part of the life cycle. Microsoft underwent some bad experiences with acquiring companies and trying to control them, so they were in a good mindset to acquire us and allow us to maintain the formula that made us successful in the first place. They were ready for hands-off management.

So, you weren't at all fearful that Microsoft would take over and run your firm into the ground?

TG: I wasn't worried about that. I never got the impression that they would try to take over. Ironically, any difficulty between Microsoft and us working together came from a lack of involvement, rather than too much.

Microsoft underwent a difficult time in the first decade of the 2000s, trying to find a good strategic plan for PC games. They had a tenuous time with trying to define their PC game strategy. They ended up with a vague PC plan, while relying more and more on PC games to generate revenue for their budding Xbox business.

One sign that things were a little off-balance at Microsoft was their meeting process. I never knew who would show up to a Microsoft meeting. We had a monthly studio manager meeting.

There were seven studios, so one would conclude that seven studio managers would attend the meeting. I would walk into a room with over 20 attendees. I never knew who all of the attendees were or why they were there. I rarely even knew the agenda. It's difficult to accomplish anything with a room crammed full of random people and no agenda.

But you personally stayed with Microsoft?

TG: I had a contract for only two years, but I stayed for eight years until Ensemble closed. I was proud of staying longer than my minimum two years. I valued loyalty as an employer, and I believed that I should value it as an employee as well. Over the years, Ensemble had a very low rate of employee turnover. However, Microsoft Game Studios saw increasing turnover in high-level management. With each management change came a new and disruptive strategic direction.

You had various projects in the pipeline before the closure. What were these projects? Why were they canceled?

TG: Some of the games we canceled ourselves. Other games were canceled by Microsoft. Some projects were discontinued after Microsoft management changes. The projects were determined to be too expensive and risky or not "in our area of expertise". Thus, we would start over on something new.

It was frustrating for employees to invest so much time on projects that never shipped. The end result was that we ended up doing a lot of Age of Empires sequels. This was fantastic, but we wasted half of our efforts on starting and stopping other new projects which were never brought to fruition.

One great game we had in the works, and in which we had invested two years, was a massively multiplayer online game set in the Halo universe. After multiple prototypes and demos, we finally achieved buy-in from Shane Kim, the general manager at Microsoft Game Studios. The game was bold and beautiful, and I was sure that this product would be a massive blockbuster for Microsoft. It was a very exciting time at Ensemble.

Did that excitement last?

TG: After another change in management, Microsoft shifted their direction, killing the Halo project in the process. Soon after that, I flew from Dallas to Redmond for a private meeting with Shane to assess the situation. It was during that meeting that he told me that Microsoft decided to "internalize" the development of Age of Empires and close down our company. While this was difficult news to process, Shane asked me if I was interested in buying Ensemble back from Microsoft. He indicated that they would come to terms on a price with some type of deal to develop the next Age of Empires.

While Microsoft may have been in the position of power to close the studio, I told him that I wasn't interested in reacquiring my company, but that I would entertain starting up an independent studio. I suggested to him the possibility of a new studio that would develop the next game in the Age of Empires series. Shane expressed interest in that, so we began working on a deal to do the next Age game as new independent studio, now known as Robot Entertainment.

What was your vision for this new company?

TG: The short-term vision was to capitalize Robot Entertainment by reinventing Age of Empires for an online, free-to-play social-game world. Our long-term vision was to develop original properties that would take Robot into a new era of games. Our intent was to shape Robot into a creative, employee-owned company.

Robot was a company born from extraordinary circumstances. When Microsoft informed me that they were going to close Ensemble, I set my mind to turning this devastating event into a great opportunity. We formulated a plan that would allow us to create a new, progressive game company with the remarkable talent of Ensemble.

The objective was to strike a deal with Microsoft to develop the next version of Age of Empires as an independent company. Our plan was bold. We had to create a design that was so compelling they would be willing to hire back a team whose studio they had just shut down. This strategy relied upon our greatest strength: our reputation as world-class designers of real-time strategy games. By leveraging what Ensemble did best, we funded and launched Robot.

Are you still oriented toward creating phenomena? Or has your experience tempered your more youthful aspirations?

TG: My experience has reinforced my youthful aspirations! I believe that creating a phenomenon is more important than ever before. With the rise of mobile and social games, there are more games than at any time in our history. The question is: why do some great games become blockbusters while others remain unnoticed?

Making superior gameplay is only part of the equation. To create a phenomenon that is a runaway success, one must create a powerful group perception. People move in groups. They want to be part of something greater, and this is what a phenomenon is all about. For example, the social phenomenon of The Beatles was just as important as the music itself. Alone, one might listen to an album, but a phenomenon can turn a group of listeners into screaming fans.

Creating a phenomenon is an art form.

What do you want to do going forward?

TG: My tenure at Robot was shorter than I planned. Despite my love for Robot and its employees, it was soon evident to me that my talents and Robot's needs were not a perfect match. In the early years at Ensemble, I hired each new individual according to my own personal criteria.

Robot employees are close friends who I had worked with for up to 15 years. In that time period, our relationships had evolved. I was no longer their mentor and father figure. Time had inevitably changed that. It also became clear that my aspirations were not the same as Robot's aspirations. It was difficult to accept at first, but Robot and I are on separate paths.

My contributions as CEO at Robot were completed after we successfully transitioned from a vision to a flourishing game studio. I've handed the reins over to extremely capable individuals who had been waiting for their opportunities to run a great studio. I remain the largest owner of the company and a member of the board. I stay close at hand to advise on important matters.

After spending a decade and a half creating, building, and guiding the team that shaped the Age of Empires phenomenon, it's again time to follow my passion and produce a new phenomenon.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like