Book Excerpt: How Game Developers Choose Leaders

In an extract from his new book, Team Leadership In The Game Industry, Firaxis veteran Seth Spaulding uses key examples to demonstrate how to pick leaders and discipline-specific leads within your own game development firm.

[In an extract from his new book, Team Leadership In The Game Industry, Firaxis veteran Seth Spaulding uses key examples to demonstrate how to pick leaders and discipline-specific leads within your own game development firm.]

So how do companies select leads? In most cases, it's a very rational process. The scenario from the company's perspective involves finding and developing new leaders as the company grows and project teams are added.

The company ideally started with strong department leaders with good management skills and a talented and energetic production staff. The need to develop leaders from the production group emerges with the company's growth.

The Ideal and the Real

The goal is always to find the right people and match them to the right role within the company. Assuming an ideally staffed and well-functioning studio, an individual production employee is seen during the course of a development cycle to demonstrate an inclination to work with others and does so effectively, usually through mentoring and in group feedback sessions at early stages.

They are recognized for their work ethic and sense of responsibility to (and sometimes beyond) their specific task lists, and as such they are offered a position as a specialist lead or sub-lead at the time these become available. At this level, they work for a project cycle or perhaps two under the supervision and mentorship of experienced art leads, other specialist leads, and the art director, from whom they receive guidance in the duties of their new role.

From there, if they prefer to remain at the specialist lead level or return to the role of senior artist, that path is open and ideally just as attractive a career option as the management track. If instead they continue to show aptitude and desire for greater leadership opportunities, they may continue to move into a greater management role, possibly as an art lead on future projects, inspiring their teams and building morale across the company.

Unfortunately, there are several possible points of failure in this sunny scenario, which seem to occur with regrettable regularity in the games industry. The most prevalent points originate from the first two assumptions -- that a studio is fully staffed and well functioning. The sad fact is, no company in my direct experience has ever been ideally staffed. The result is that the candidate pool for leaders in an organization is probably going to be sub-optimal, particularly when a studio moves to multi-project development.

Even if your company is staffed with a dream team of talented, experienced, and driven individuals, there is no guarantee that any of them are going to have the aptitude or desire to manage. The possible solutions then amount to selecting a candidate for a lead position with reservations about his or her potential for the role or looking outside the company for a candidate who more closely meets the job description.

Either choice can be problematic; indeed, for a small developer, the latter may be impossible. Due to production schedules, it may be highly unlikely that even a mid-size developer would choose to begin a possibly lengthy search when the need of an individual to fill the role is immediate.

The second assumption -- often unspoken -- is that a studio is well functioning or perhaps rationally functioning. As far as lead selection goes, the issues of favoritism or nepotism and simple inexperience do exist and, in the case of favoritism, can be extremely dangerous even if it is merely perceived to exist. Suppose, for example, the best person to lead a project happens to be the president's best friend. If you find yourself justifying a lead selection by including his or her social relationship as a factor in any way, it may be perceived very poorly by the company.

That negative perception should disappear to a large extent if and when the individual demonstrates effective performance in the role to the team. Even still, the idea that favoritism exists in an organization however small or large can be very detrimental. A far worse scenario emerges when this hypothetical individual is not qualified or is perceived to be not performing to expectations and no action is seen to be taken by senior management.

Inexperience, while an innocent and recoverable condition, can lead to many problematic leadership selections. The most common errors based on inexperience involve selecting leads based solely on production art, design, or coding skills. The result is often a lead who is most comfortable doing the job that he or she has always done and trusting that the team will take care of itself from a supervisory perspective. Few if any teams are capable of this; indeed, selfmanagement of this type is impossible for larger groups that require interdepartmental communication coordination.

In many ways, the process of selecting a lead from an internal group of candidates should be looked at as a job interview, with all the positives and negatives that go with that event. If you have ever had the experience of interviewing and failing to get a job, you know what that rejection can feel like. Now consider that a valuable employee has had that ego-damaging rejection and tomorrow they have to go in to work, smile, and do a great job. Managers need to recognize the individual goals of their staff and not let an internal rejection for a lead role spiral into a negative outlook on their prospects for career advancement within the company.

In some instances, the number of hypothetically suitable lead candidates can also cause problems. As we saw in some of the organization charts in Chapter 2, "The Anatomy of a Game-Development Company," there can be three or more specialist leads per project working under each art lead. Presumably, some or all of these specialist leads will want the opportunity to be what I'll call a "full lead" at some point.

Typically, not all of these candidates will be suitable or will even want a full lead role for any number of reasons, but the situation can be complex in some instances. The director and other managers must at times make difficult decisions between internal lead candidates based on the criteria they set for the position. These decisions will always disappoint at least one prospective candidate and will disappoint them for a considerable amount of time given the multiyear length of current development cycles for AAA games.

In these cases, management needs to provide very clear expectations of the role, honestly assess each candidate, and communicate the decision-making process to all parties. In addition, future commitments for lead roles, if they are made, need to be kept. Instead of telling a rejected candidate, "You'll get the next lead spot that comes up," I recommend something with more flexibility, like "I greatly value your contribution at all levels and as appropriate, I am going to work to make this company match your career goals."

On the opposite side of the spectrum are cases where a potential or proven solid lead needs to be persuaded to take the role for a given project. This is ultimately a no-win situation. In such a case, it would be plainly evident that any sort of passion for the project was missing, and I feel that passion is a key characteristic of a lead. That said, there are occasions when the situation calls for just such action.

At the GDC Art Director/Lead Artist Round Table in 2005, I asked attendees what motivated development production personnel to become leads; surprisingly, the answer from a number of participants was "more money." If you find your company in this situation, take a close look at the list of responsibilities on your leads and pay attention to the overtime being logged. These experienced individuals are key to your company's continued success, and they should be supported, and their quality of life considered, every bit as much as every other staff member.

Finally from the Pandora's box of what can go wrong, leads can fail. They can decide that the move to a lead role doesn't appeal to them for any number of reasons, or the team and management can make the determination that they are not performing to expectations. Perhaps they fail to motivate their team, or they lack the skills to cooperate with fellow leads and effectively communicate to the team from a position of power.

Management in this event is forced to make a decision to either move them out of the role and find a more suitable lead or support them through the project if the issues are not so severe or circumstances simply dictate this strategy. Obviously, neither of these options is desirable, but at the point that the determination to remove the lead is made, it is vital that management take swift corrective action.

The following case studies of unsuccessful leadership examples represent composites from my own experiences, observations of colleagues around the industry, and tales from others -- many coming out of the Art Director/Lead Artist Round Table at GDC. I would like to point out that I have enjoyed a great many successes and worked with a number of talented individuals, many of whom are interviewed throughout this book.

However, it has been said that success is a poor teacher -- and I can confirm that the most valuable lessons I've learned have come from making painful mistakes on the job. The second most valuable lessons have come from hearing about the painful experiences of other people and taking lessons away. This second tier may be a bit less effective, but they are also a lot safer for your career and gentler on your psyche.

Case Study: Rick

Background: Wrong Person, Wrong Role

Rick was a studio director hired into a mid-size, one-project development studio. He was formerly a high-level project manager at an entertainment giant that was highly respected but outside the game business. Rick had no previous software experience but had managed substantial teams in the film and broadcast industry. The game studio had produced one hit game and was working on its second. Senior management at the developer hoped that his experience would bring some manner of order to what they felt was a production process that was beginning to drift and was losing momentum.

Despite having one hit game, they were looking to greatly increase the capabilities of their engine while developing the next game, and the process was floundering. Rick's credibility for the role stemmed entirely from the credentials of the entertainment giant with which he had previously been employed; the studio's senior management also factored in the business connections that Rick could bring to the them.

Once in place at the developer, Rick began to reorganize the staff and brought in two former associates. From his very first days, it was clear to the mid-level managers that he had no idea how to run a game-development project or a studio. The cultural difference between the small development studio and the entertainment giant from which he had come was immense, and he made little effort to find common ground -- probably in part due to his complete unfamiliarity with the software-development industry.

Rick was in a difficult position; he was expected to come into this struggling developer and make a positive difference, to bring a slice of the success enjoyed by the entertainment giant. The problem was that he had no idea how to translate the skills learned at the entertainment giant to a high-functioning staff at a small game-development studio. He began to create political camps similar to what existed at his previous 1,000-plus employee company. By holding private meetings with staff in which he complained about other leads and employees, he created divisions among the development staff, pitting artists against programmers and even leads against each other.

The result of this cultural chasm and sudden political infighting was a series of poor decisions that eroded the morale of the leads as well as the company. Initially, senior management at the developer was resistant to hearing complaints or seeing any warning signs. Even when they did see these signs in concrete fashion, they were very slow to take corrective action. Indeed, management was slow to take action even when it was apparent that severe problems existed, in part because Rick shielded senior management from the realities of the situation.

For example, Rick tasked one of the leads with writing a postmortem on a recently completed project. The lead approached the postmortem in the industry-standard fashion, providing an overview of the project, discussing five things that went well, and discussing five things that went poorly. After reviewing the postmortem write-up, Rick spoke to the lead privately and said that he wanted "the bad stuff" taken out -- a comment that sounds laughably naive to anyone who has been through at least a couple development cycles. There are always at least five issues from any development project I've ever worked on that need attention and improvement from cycle to cycle.

These issues occur because we work in an imperfect world and frequently reach for new, never-before attempted technical, artistic, or design achievements. These are not issues that get people reprimanded or fired; instead, the issues raised in postmortems -- and the postmortems themselves -- should be considered part of the development process. Rick, not having ever experienced this, made a very bad decision with the intention of protecting himself or others politically speaking. This, of course, resulted in a further lowering of company morale once the story spread around the office.

During Rick's first year as studio director, more than a quarter of the staff at the developer resigned in disgust. Not all of this lack of retention can be blamed on Rick, but his errors and the blind yet unwavering support that senior management gave him changed the atmosphere at the studio for the worse.

When employees don't think management is paying attention to the studio and the concerns of their key leaders, bad things are going to happen. The studio lost another third at the end of Rick's second year, at which point management finally requested Rick's resignation. By then, however, the damage had been done. The studio was down to a skeleton of its former self, project development was moving at a crawl, and the money was running out.

Analysis

Could management have spotted the error in bringing Rick on board and corrected it sooner? Even more importantly, could they have made a better hiring decision? Should they have listened more closely to their key production leads? The answer to all these questions is an emphatic, "Yes, of course they could have" -- yet the management group did not. Why?

Ego Issues

First, they had committed considerable resources to bringing Rick on board both in terms of his salary and of the corporate cachet they imagined would result from bringing in a person from an entertainment giant. The idea was that Rick could separate himself from the entertainment giant but bring with him that culture, that process, whatever "it" is that the game developer wanted. Attaining otherwise unavailable expertise is a very real and compelling reason to hire a leader from outside the company.

The key is to clearly identify your need and match that need with an individual who has a proven record solving just that problem. The studio's senior management team was perhaps dazzled by the title and the corporate glare of the entertainment giant and missed the fact that Rick simply was not qualified to do the job.

Rick bears some responsibility in this case as well; he should have spent some amount of time absorbing the studio's practices, learning its culture, and learning about the game-development industry as a whole. The fact that he did not perhaps points to an issue of egotism, which explains many of his actions. Senior management was guilty not of protecting Rick so much as protecting the correctness of their decision to hire Rick and not taking swifter action once the issues with Rick were obvious.

Lack of Open Communication

Beyond the resource commitment and the ego issues, the senior studio managers, assessment of Rick's performance was based on information received from Rick himself, who was in daily contact with them and controlling the message. The only other information sources were senior employees and leads who were courageous and desperate enough to go over Rick's head and warn the senior managers.

The problem was that senior management had been listening to desperate complaints about the lack of a studio director for months prior to hiring Rick. Now they had an expensive, experienced studio director from a well respected entertainment giant and their employees were now complaining about the person. Naturally, they felt a certain amount of frustration, however much they may have respected the opinions of some of the staff.

After Effects and Corrective Action

The fact that senior management waited to take action until key staff members left points to a considerable disconnect with their own studio. In this case, the results of an exit interview from a senior designer led to immediate action. This is a great example of an exit interview's usefulness. However, it should be noted that six prior exit interviews produced no similar result. It is possible that the seventh interview produced a tipping point in terms of the weight of evidence, or perhaps the interviewee had been a major contributor and thus was listened to more closely.

Another possibility is that none of the other exit interviews mentioned Rick -- and herein lies a danger of relying too heavily on exit interviews for honest assessments of what may be wrong in your studio. The game industry is still a rather close-knit group, and prudent employees will very often avoid calling out senior managers or leads in writing in an exit interview. You never know where your career will be in five years, or where the career of a director such as Rick's will wind up. Getting to the core of why an employee is really leaving is not that difficult if you as a management group have effective communication paths with employees at all levels of your company.

Note

A similar situation was discussed at the 2007 Art Directors' Round Table during a segment devoted to the effects of and solutions to problems caused by poor leadership. The participant from a mid-size studio described a senior manager who was legacy, but was incompetent and intractable and causing problems across the team. "What did you do to correct the situation?" I asked. "I quit" was the immediate answer.

Case Study: Victor

Background: Right Person, Wrong Role

Victor was an art director and lead artist at a small, one-project company. The subject of a lead/director split emerged when the company grew to two- and then three-project teams with a corresponding growth in staff. Victor expressed the strong desire to remain director but also keep his hands in production as a lead -- an option that was afforded him based on his level within the company, his strong performance to that point in his role, and a miscalculation regarding the amount of management time that would be required to build and maintain a strong department.

Along with his director duties, Victor assumed the lead on the largest and most complex project while two other artists were selected for lead roles on the other games. Victor would oversee art development on these projects in the role of art director.

The company expanded very quickly and the management time commitments grew correspondingly. Victor, however, insisted that he maintain some projectlevel control because he felt that doing otherwise would lead to his production skills eroding and eventually lead to the loss of his ability to work in art direction at the company. Such fears are not uncommon, and are not totally unfounded either. As noted in Chapter 1, "How We Got Here," the game industry's technical advances happen very swiftly. Art-creation tools and methodology, as well as programming for different system architectures, can evolve considerably across the industry within the span of one project cycle.

Skills can become obsolete if one is not in a production environment during the transition or acting as a lead or director and involved in management on successive projects for a few years. The willingness to surrender reliance on production skills as a foundation for a professional is a huge psychological hurdle for directors in particular to resolve. These skills usually have been built up for years and have attracted many compliments as well as afforded the individual many professional opportunities.

To set those skills on which one has built a career aside and make a commitment to a management track is huge career decision -- one that should not be taken lightly. At the lead level, the concern is not perhaps as severe. Leads frequently are involved in production work and can often move in and out of the lead role depending on the project and studio needs. It can be a terrifying step, though, moving to the director level at a multi-project studio where your future power app looks like Microsoft Excel.

Note

The validity of this concern is reflected in the comments of one art director at the GDC Round Table, who noted that "The lead needs to be the one who can break the biggest bone." At some point during the Round Table, I usually say "Please raise your hand if you are an art director at a multi-project studio. Keep your hand raised if you still do a lot of production artwork." I do so in part to show the artists and lead artists in attendance the price of management in terms of production time lost due to time spent developing and maintaining technical skills.

Nonetheless, I'm always stunned by the large number of hands that remain raised -- typically about 80 percent. Interestingly, but also entirely anecdotally, some attending art directors have also expressed amazement at that high number in private one-on-one talks after the round table has broken up.

In Victor's case, he began managing his project as lead and giving wide latitude to the other art leads. The three leads met together once per week to compare notes and review project status, but Victor was never able to devote enough time to dig into preproduction efforts, art pipeline development, or personnel issues emerging on other teams. Few of these errors are ever apparent in the early stages of production and preproduction because so little is known about the project and early milestones tend to be softer than later ones, which require more game functionality and art polish.

In other words, it's easier to get away with stuff in the first third of a project if you don't have active and experienced oversight. Victor was not able to provide either, and chose to put the majority of his time and focus on the art lead duties for what was the largest project at the studio. There's nothing wrong with this arrangement in one-project studios, but in a multi-project studio, the director level exists primarily to supervise and support the department staff and project leads.

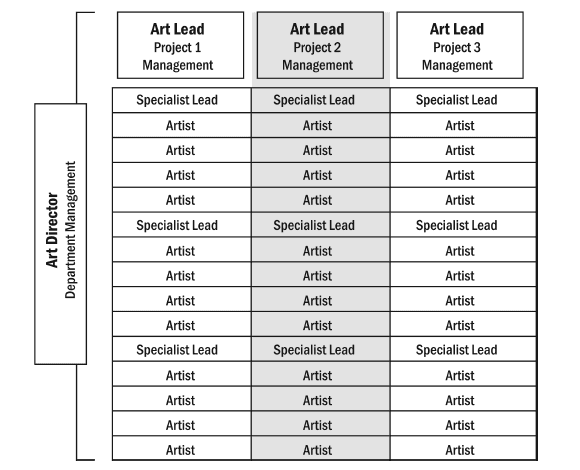

As evidenced in Figure 3.1, the departmental-supervision role is not insignificant. Ultimately, a few of the company's projects were cancelled over the years. These cancellations weren't necessarily related to the issues around Victor; some were due to the vagaries of the industry. Nonetheless, some were related to situations like his, which were found across all departments of the company.

Figure 3.1 A dual-matrix management structure representing a 48-person art department in a three-project company.

Analysis

Inexperience

The leadership failure in Victor's case is one of him and his fellow directors not having the experience of running a larger company or an understanding of the associated organizational needs. Victor was simply unable to manage the role of art director after the company reached a certain size. It was difficult to see the tipping point where project duties became so time consuming that departmental issues were suffering because the departmental growth occurred gradually, over a period of a few years.

During this time, both project complexity and Victor's department size expanded rapidly. By the time the company had been running between two and three projects simultaneously for a few years, Victor and the other senior managers had begun to sense the problem; subsequently, they and Victor decided that it was not in the best interests of the company for him to continue to devote time to both jobs.

He ultimately chose the role of lead artist over director because he felt that he gained more professional satisfaction from facing project-level challenges. He was also able to address his concern regarding the loss of his professional skills by this decision. A new director was promoted from within the art department, who immediately began making very positive and overdue adjustments to the department both in personnel and practices.

An ironic downside of Victor choosing to focus on the art lead role was that while his production skills had not declined very much, his ability to stay current with new practices and software had suffered. As a result, the succeeding projects at that developer did have quality issues that might not have existed had management recommended that he simply move into the director role, where his greater strengths may have been.

Founder's Syndrome

The practice of senior managers clinging to roles is particularly thorny because there are simply fewer people to tell themthe honest truth about the effect of their dual focus. The term "founder's syndrome" describes the condition that develops when founders or long-term legacy employees make decisions based on things as they were, not as they are.

The hope is that based on the level of their experience and maturity, they are more capable of grasping the situation and taking selfdirected action to change it, but the causes of inefficiency, poor project results, and poor retention are not always so clear as to point to a single problem that needs to be addressed. Self-awareness and awareness of project- and organization-level needs are also not given traits, regardless of level of talent and skill sets.

After Effects and Corrective Action

The company moved to clearly define the scope of responsibilities for all employees all the way up to the executive group. Some other directors shifted titles and responsibilities, in addition to Victor finding a more appropriate role. What emerged was a more focused leadership group that was able to effectively lead a growing company without project needs distracting half of the directors.

Case Study: Xavier

Background: The Best of What's Available at the Moment

Xavier was the lead programmer (and tech director by default, since there was only one other programmer) in an eight-person startup that experienced a two-fold growth after one year. He was a very friendly person whose contribution to the social fabric of the small company was considerable. He frequently led and organized movie nights, dinners, and other out-of-office events. After the completion of the first project, however, questions arose about Xavier's ability to lead a growing tech department.

These questions centered around an inconsistent work ethic, insufficient technical skills, and at times insufficient communication skills. Specifically, although Xavier received feedback on his coding, he showed resistance to actually implementing the feedback directives and multiple iterations were frequently required to achieve a desired result. At around the same time, and prior to any message from management about poor performance, Xavier expressed a desire to move into more of an audio role.

This was something the studio needed, and Xavier had been a musician at one point in his career, so it was decided to move him over to a programmer/audio engineer. Xavier completed one project in this role, after which it was determined that Xavier, while a good musician, did not have the skills to be a game audio engineer. At this point, management was distracted to a degree by studio growth and the potential building of a second and then third project team.

Because the company was about to expand into a multi-project studio, this serious issue of what role to find for Xavier was seen in one light as a happy opportunity to solve two problems -- where do we find a producer for the new projects and what do we do with Xavier? Xavier also recognized the need for production work on the coming projects and suggested a move to a producer role.

The move was made, and Xavier began to learn the skill set of a producer, mostly centered around MS Project. He produced one project successfully, although there were inefficiencies and friction from some team members; this friction centered around his aforementioned communication issues. Xavier seemed to perform well enough on the second project, although the project experienced a difficult development cycle and arrived a few weeks late.

In postmortem comments from the team gathered a month after the project shipped, the art lead expressed his unhappiness with Xavier as well as his unwillingness to work with him on a future project. Now the problem of what to do with Xavier became more intractable; at that point, six years into his tenure, management decided to terminate his employment.

Analysis

Failure to Address Negative Performance and Take Effective Action

The prominent leadership failure in this study has more to do with senior management's behavior than with Xavier's possibly sub-par leadership skills. In fact, we know very little, based on the information here, about exactly what the roots of his professional leadership inadequacies are. Regarding his difficulty implementing feedback directives, we should consider that perhaps the directives were not clearly given or perhaps phrased as suggestions. We don't know. There is usually not one person at total fault in cases of communication problems.

Most of the performance criticism that Xavier experienced could be subjective; without more explanation and examination of the specific occurrences, we cannot make any judgments. What we do know is that upper management did very little to support and mentor him, or to really get to the source of his difficulties. Instead, management chose to not directly address these issues, to focus on his positive contributions, and to try to "find the right role" for him in the organization. The opportunity to accommodate this mode of thinking occurred because the company was growing and roles were quickly expanding.

There is nothing wrong -- in fact, I view it as a positive -- with trying to find more appropriate roles for people in an organization and working with employees' career goals to that end, provided that the role is truly needed and the individual is capable of performing well in that position.

The negative issue here is that management seems to have addressed recurring perceived negative performance in one position by transitioning Xavier to another role in the company. I've gathered that this seems to be a more common occurrence than one might suspect in talking to others in the industry over the years. Indeed, I've heard of similar transfer practices in almost every discipline from participants in GDC Round Table discussions of problematic employees.

Why do this? Why not confront the employee? Why burden another department with what you know, or strongly suspect, will be a recurring problem? And, most of all, why promote them? These are all the questions that the top performers in your company will be asking when they see no action or inappropriate action taken regarding perceived inadequate performance.

I would preface the answer to these questions by maintaining that there are very few dumb people who are in business. Everyone does things for at least what seems to them to be good, logical reasons based on the information and conditions at a certain point in time. It is sometimes only in hindsight that we can examine and evaluate questionable decisions, but it is vital that that examination and evaluation take place.

In this case, the project needed a producer quickly, and management may have, generally speaking, truly valued Xavier's contribution to the company and felt that, initially, the path of least resistance -- transferring him to that position -- was preferable insofar as it kept his morale up. Besides, and maybe more likely, it may have been that no one wanted or had the skills themselves to intervene in an effective way. This is not uncommon in a small or even mid-size company.

Xavier was chosen as lead because he was in a very small sample group that required people to function well in multiple roles. ...Almost every individual in a small company is fulfilling duties in more than one capacity. It is normal and expected that not everyone will excel at every spot all the time. As a company grows, then, management must have the discipline to evaluate staff based on their performance in every area and make appropriate decisions when growth does occur and roles need to be clearly defined.

Failure to Provide Support

Once in a leadership role, Xavier was getting very little support in terms of developing new skills or correcting perceived problems. This follows directly from the fact that to begin with, no one directly confronted him on his performance issues. Management also failed to provide leadership or management training to anyone at this time. Now in the role, all the directors could do was hope that professional growth and competence would occur spontaneously.

It should be noted that although we know very few of the details of Xavier's troubles, the fact that he experienced the same sorts of general problems in three different roles indicates that he did probably have some genuine issues to which he was at least somewhat obvious. In this case, lacking consistent and timely feedback, he felt only that certain people in management were difficult, or saw him as difficult, and that for the most part, the team was very happy.

After Effects and Corrective Action

After Xavier's employment was terminated, the management group recognized its own failures in the process. Members in the group came to few conclusions regarding leaders in general moving forward, but they did acknowledge that there was no clear message of performance dissatisfaction being delivered to the employee in a useful, consistent manner, with expectations for improvement stated, and that a general lack confrontation on issues surrounding poor performance was a company-wide management issue.

As a result, a more diligent review form and process were created, and a clearer description of the producer role, among others, was developed. Management realized that they acted in the fashion they did because they felt that the producer position was needed quickly and, ultimately, they were over-accommodating what had become a difficult, legacy employee. In the end, choosing not to start a search for a skilled producer led to a reduction in office morale over the course of a project, a messy termination, regret over the situation among some, and, of course, a need to hire a skilled producer. The positive effects that came out of it were a better understanding of roles and responsibilities and clearer communication of role expectations generally across the company.

Case Study: Yvette

Background: There Is No "I" in Delegate

Yvette was promoted to art lead on a project of 10 artists after two years as an artist in a mid-size company. She was an especially active artist, contributing assets and ideas above and beyond her specific responsibilities. In concept meetings, she was very vocal regarding creative ideas and best practices for the art pipeline.

Moreover, she enjoyed a very effective collaborative relationship with the lead designer, who many considered to be exacting and sometimes disengaged with the team. At about the one-third point in development, the original art lead was removed to kick off another project, leaving a vacancy for Yvette, who was approached about the possibility. Yvette accepted the role and the team was very supportive regarding the transition.

The project's art production was just getting underway, and Yvette threw herself into almost every aspect of the art-asset pipeline-updating practices and personally editing or requesting re-dos on a number of art assets. The net effect after a few months was a considerable improvement in the graphical look of the game.

The high degree of rework was seen as a minor negative by the art director, but he trusted Yvette to manage the overall schedule appropriately. Yvette had also wanted to redo the opening movie, done by a contractor, and see it expanded in scope and completed by an internal team. The art director vetoed that idea in favor of having the same contractor rehired to make edits to the original piece.

As the project proceeded, Yvette continued the practice of editing or, in some cases, redoing sub-par assets. She also assigned herself the task of completing the user interface (UI) alongside her management duties. This was a huge undertaking whose true scope was not fully appreciated until it was too late. The UI component of this, as well as many other games, is a fluid asset that can change substantially up to the last minutes of development time. In this particular game, the UI was also more complex and robust in terms of features.

At this point, an art director should have intervened, asked for a time estimate on the task, and suggested strongly that the UI be delegated to a team member. In this case, however, the art director was also the art lead on another project, and was not fully aware of the specifics of the task assignments on Yvette's project. The result was that Yvette's time was increasingly devoted to production tasks and less focused on overall team performance and team contribution.

As an example of the negative effect of this focus, an artist on the project at one point deviated from the set pipeline and created a complex asset with an unproven and, it turned out, buggy plug-in for the 3D application used for asset creation. The result was a piece of art that caused headaches for months until the problem was diagnosed and a fix could be made. The fix required the asset to be rebuilt almost from scratch. Proper attention to timely asset reviews would have spotted the error in early development and perhaps prevented the loss of production time associated with it.

As the project reached completion, Yvette was staying roughly on schedule, but regularly working 80-hour weeks. The art director had been pulled into production to help finish the user-interface tasks and was also unable to keep attention on the team and the department as a whole.

The resulting game was attractive and commercially successful, and the company was proud of their effort, but morale in the art department had suffered in noticeable ways. During the project, individual artists didn't put the same level of care into their own contributions, feeling that the art lead was just going to change it herself if she didn't like it anyway.

Prospective leaders in the department were now wary of the time commitment involved in accepting a lead position. And most damaging, Yvette was now completely burned out. She resigned from the company a few months after the game released. The result was that the art department was missing a senior artist, and an experienced lead, and had a department full of artists who needed coaxing -- of the financial and emotional variety -- to consider a lead artist role.

Analysis

Inexperience

Yvette was a dedicated and accomplished senior artist who may have made a great lead on the project -- if she'd had experienced support available to her. Some of Yvette's performance issues, such as her taking over sub-par assets, shows a commendable commitment to the quality of the product; properly channeled, that energy could be an extremely positive force on a project.

As the energy was applied, however, it led to a disassociated team and a burned-out lead. The management team, especially the producer and art director, should have enforced a limit to production-schedule commitments. The art director in particular should have been more involved in mentoring Yvette, and should have required her to delegate asset edits to the artists who created them. That they did not is probably a case of simple inexperience.

The assumption of the user-interface element of the game by the lead also contributed to the problems late in the game's development, but the blame for that does not rest on Yvette's shoulders. Rather, it rests on those of the management team. No lead should be tasked for production code or assets more than a certain percentage based on the number of direct reports; moreover, no lead -- art or technical -- should assign themselves any task that involves major dependencies for other team members. An example of this might be developing an animation pipeline or leading visual-effects creation.

Understanding and Supporting the Role

The lead's primary job is to make sure that everyone on the team is working at peak efficiency, and that they have no resource needs or obstacles preventing them from completing their tasks. Critical management and review work can far too easily take a backseat when the lead is tasked in the production schedule -- and that eventually makes the entire team work at less than peak performance. It is vital that this shift of mindset, from production to management, take place for a leader to be effective.

In the case of Yvette, she went from 100 percent production one week to being named the art lead the next, without any real adjustment in work practices or scheduled tasks. As a compounding factor, there was never an opportunity for Yvette to explore the role of the lead or to learn leadership skills as a specialist lead on a project before diving into the full lead role. This situation is sometimes unavoidable in small or mid-size companies that do not have great staffing flexibility or resources, but the absence of this step should not be overlooked as a reason for Yvette's problems. Given that Yvette was a new lead, she should have beenmentored andmonitored muchmore closely by the art director.

Note

By "mentoring" and "monitoring," I mean meeting one-on-one with the lead as opposed to hovering over the lead's shoulder. The new lead must be given the opportunity and latitude to truly lead the team on his or her own; having the director physically there undermines the lead's authority, and usually causes the lead to simply defer decisions to the director if present. Mentoring and monitoring should be done away from the team for this reason.

After Effects and Corrective Action

Following the completion of the project, and for many years afterward, the company in question was forced to offer a "lead bonus" to candidates in order to get staff to consider lead roles. While many companies follow this practice, I consider it to be a bad idea; instead, I try to foster an environment where a senior artist or programmer is every bit as valued, appreciated, and compensated as a lead with comparable experience and contribution levels. It's bad enough that the lead on the organization chart gets a bigger box -- and is at the top of the credits -- but if one side of that equation is also getting a salary bonus, even a temporary one, it further erodes any attempt to equate their importance to a project.

And besides, sometimes even the money wasn't enough of an incentive. Some of the most accomplished artists at the company refused to consider lead roles due to the perceived lack of support for the position, the associated personnel- management headaches, and the amount of overtime that was required. Over the course of a few years as the company modified its practices, that perception did change, but it was certainly a challenge that the management team could have done without.

Other practice changes that the company adopted in part because of this experience included external management training, role and responsibility clarification, and weekly one-on-one art director asset reviews.

The management training was made available to every new lead and director in the company. An external leadership forum focusing on new managers and leaders was selected for the first try. While it wasn't an overnight success, it did lead to a more professional approach to management in the company, gave managers a heightened awareness of their new responsibilities, encouraged further education (mostly through the reading of management books), and gave new managers a starting vocabulary and skill set with which to do their job.

The clarification of lead responsibilities included a different approach to personnel management. Hereafter, the lead was responsible for basically as much personnel review or performance critique as he or she wanted. Typically, this took the form of the lead giving an initial performance talk to the employee when warranted due to underperformance in some area. The director would then take the situation over if further corrective or disciplinary action was needed.

This was more or less the way it worked before, but communicating that to prospective leads turned out to be very helpful. One of the most difficult things for new leads to figure out is how to give feedback from a position of authority to people who were formerly peers. With the potential personnel-management aspect removed, senior management found new leads felt much more comfortable.

The art director reviews began immediately, but were only truly successful and productive when the art director stopped also being a lead artist and could devote his or her full attention to the needs of the other projects Unfortunately, this development did not occur until there was a personnel transition at the art director position, some four years after Yvette's departure.

Case Study: Zeke and Alan

Background: A Tale of Two Leads

Zeke was a skilled designer who was new to a mid-size development studio. He brought newer game genre experience to the team and was very energetic and aggressive regarding schedules and abilities. His first assignment was the lead on a prototype project in which he was the primary designer of two on the project. The project was extremely successful and his efforts on the project were lauded by all, to the notice of senior management, who pegged him as a potential future lead designer.

One issue for senior management was Zeke's relatively low level of job experience and his newness to the company. To answer these critiques, senior management decided to pair Zeke up in the lead role with Alan -- also a new designer but with a bit more industry experience and a slightly longer tenure with the company. Alan, it was felt, had a more traditional approach to working in a team and had demonstrated his ability to do so; the thought was that his more even, mature presence would balance out Zeke's exuberance and allay management's concerns in this area. The goal was that the two would work as dual leads on the project with a clearly defined split of job responsibilities, and neither having authority over the other.

Once the project was underway, the relationship and communication between Alan and Zeke began to deteriorate. Most of the disagreements centered around the basic approach to the design, and there was purposely no chain of decisionmaking authority between the leads. Alan doubted Zeke's general approach, and Zeke responded to the situation by quietly taking on more and more design features to the implementation level.

Senior management appealed to a senior design director for advice on which approach was truly best; unfortunately, the director could only equivocate, saying it was too early to tell whether Zeke's approach was too aggressive or Alan's was too conservative. After a couple of months of this quagmire, Alan and Zeke both expressed their frustrations with the situation to the producer and to senior management.

The odd thing as far as senior management was concerned was that the project itself was outwardly on track; milestones were being met, and features were being implemented. If there was really a problem, then it was at a level that was deep within design philosophy and methodology and dependent on significant senior designer analysis, which was inconclusive. For their part, the tech lead and the art lead were both reasonably satisfied with progress but wary of the growing rift between their two lead designers.

Matters came to a head when Zeke and Alan separately asked management for a resolution that eliminated the dual design lead spot. Zeke, for his part, felt that he should be the lead. He argued that he had, to this point, done most of the design work in the game, and it was logical to select him as sole lead based on this fact. Alan was so worn out by the situation that he consented to the arrangement -- as long as there was no credited title change. Management expressed concerns about Zeke's perceived divisiveness on the team and in the company but ultimately consented.

Now fully in charge of game design, Zeke threw himself into the development of the game and very rapidly brought it to a playable state -- not a fun state, but a playable one. As the project entered the alpha stage of development, more questions were asked about why the game was still not yet ready, and why there were still significant design problems.

Zeke was seen to be working diligently for long hours but reacted very defensively in response to questions and negative feedback, dodging responsibility and, ultimately, resigning from the company, and leaving considerable ill will on both sides. The game design was then overhauled and missions and levels completed by a senior designer, who was pulled from another project, and by Alan, whose opinion of Zeke's design work had now found more favor.

Analysis

When Two Heads Are Not Better Than One

There is a very good reason that we elect a president and a vice president as opposed to two presidents, and that throughout all of human history you rarely see dual kings: It simply does not work very well. I've seen it tried a few times and heard anecdotally from some GDC Round Table attendees of its effectiveness, but only in very specific cases with individuals whose workflow and nature lend themselves to operate effectively in that arrangement.

The vast majority of stories I hear are tales of woe-some ending in a whimper, and others with a spectacular cataclysm. And this is not a secret. It's not something that has never happened before. Anyone who has ever worked on a group project at school where no leader who has any authority is appointed can probably tell you a funny story about how excruciating the process was and how awful things would have turned out had they not done the whole thing themselves at the end. At the project leadership level, it's the same story -- except one person can't do everything, and it's not at all funny.

So why would management, a rational and intelligent group, consent to this? Why didn't they change it the moment they saw it going awry? Why did they ultimately make the wrong decision?

The Project Staffing Trap

An unusual staffing arrangement like this comes into being because there is no ideal candidate in whatever discipline to put into the needed position. This is a bad situation for a company to be in -- so bad, in fact, that one of the only ways to make it worse is to put two non-ideal candidates into the position, with neither having final decision-making authority. The obvious rationale behind the decision is that a weakness in one lead will be compensated by a strength in the other and vice versa. It's a great theory, but it just doesn't seem to work.

The solution is simple and equally obvious: Hire the right lead designer -- someone who has a proven track record of making great games and being a solid team leader. The problem is that great lead candidates, design or otherwise, are not easily found. The process can be time consuming and expensive for the developer. Let's assume that a developer is pitching a game to a publisher that would require them to hire a programmer with some advanced ability on a new console system.

They cannot hire a candidate or even realistically start a search without a signed contract. Doing so would not only be expensive, but they could potentially lose an ideal candidate if the pitch or contract negotiations were extended for a significant period of time. It's worth noting also that the period immediately preceding a new project starting is one of the most fiscally dangerous times for an independent developer.

Cash reserves are usually at a low point, and the idea of extending into a line of credit with no signed deal on the table to back the loan up is not something that the principals of the developer or their bankers are all that happy about. Another factor to consider is the new hire himself or herself. Does the company feel comfortable hiring and relocating an individual only to have to fire that person immediately if the project deal collapses for some reason? The ethical answer (for me at least) is no.

Now, weeks or months later, the developer has the executed contract in hand and is ready to find and bring in their console expert. The problem is, they now must also start preproduction if they haven't already -- and the search itself, if not immediately successful, could take several months depending on the job market and the location and reputation of the developer. This situation is what makes many small and mid-size developers look internally whenever possible for senior and lead positions on projects.

Management must now ask themselves, do we wait who knows how long to find our great hire, or do we look internally to a quantity that is known but questionable for whatever reason? It's a tough call. That iffy internal candidate might be great. I've certainly seen many examples of individuals who successfully grew into their role, despite the fact that many had questions regarding their suitability at the start.

There is a tipping point at which an internal candidate is regarded as a potential lead who needs development and is worth the risk or is regarded as a great senior-level contributor who needs to hear an honest assessment of why he will not be considered for a lead spot (and, if applicable, what steps he or she would need to take to be so considered in the future). It needs to be recognized that it is a very subjective judgment, and senior management may not be able to reach unanimous consensus in some cases.

While there may not have been conclusive evidence that a qualified lead designer needed to be hired externally at the time in this example, there were a number of stakeholders involved in the decision who had serious reservations about the dual-lead plan from its conception -- including both Alan and Zeke.

After Effects and Corrective Action

Alan was promoted to the lead role following the completion of the project and vowed never again to attempt a dual-lead arrangement. Zeke left on a sour note toward the close of the project; by then, the design department as a whole was convinced that a change had to be made and that the removal of Zeke was the correct decision.

Lessons Learned

These case studies predominantly illustrate the problems inherent in how we select and develop leads as opposed to issues of leadership quality. The major reason sub-par leads get selected from an internal pool is we don't really thinkabout defining the responsibilities of the lead the way we would if we were launching an external search for the best candidate. This attitude almost ensures that a less than optimal candidate will find himself or herself in a lead role.

It might be assumed also that if management developed and adhered to a set of responsibilities that defined the lead role, we would see less promotion from within and more of an emphasis on bringing in external expertise. Possibly, but I would counter that defining the role, communicating expectations to the company, and demonstrably supporting existing leads will encourage internal staff to realistically assess the position and determine whether they want to pursue it. If so, the company will quickly see their internal lead candidate pool grow in ability and number.

If an individual understands and meets those leadership qualifications and is enthused about the leadership aspect, then senior management has done a good job. If, however, no candidate is deemed appropriate for the role, or a qualified candidate needs an amount of cajoling deemed extreme to consider the role, I strongly recommend if at all possible that an external search be performed. The cost will be high to find such an individual in terms of time lost for the search, but the cost of putting a poor leader in place will be far higher in a year's time -- not to mention by the end of your development cycle. As seen in these examples, the cost is not just felt by the lead, but by the entire team or company.

The subject of hiring an external person into a leadership role comes up occasionally. This can be a delicate situation with regard to senior staff who are looking to advance their careers and who feel closed out when senior management resorts to an extensive external search to fill a lead position. Where appropriate and possible, hiring from within is almost always preferable to bringing in a new hire to lead a team. There are notable exceptions, however, such as instances in which some specific technical or creative ability does not exist within the company. Such cases can exist in any department -- a specific platform expertise in programming, game genre, in design or art. The team will respect and probably strongly encourage seeking outside hires in such instances.

Interview: Joe Minton, President of Digital Development Management (DDM)

As president of DDM, Joe runs the Support Services division, which assists clients with contract negotiations, overcoming development hurdles, working with the project's stakeholders, and aligning their corporate structure for long-term success. He also oversees the process of making DDM into the model agency for the video-game business.

As president of the development studio Cyberlore, Joe was responsible for overseeing the day-to-day operations of the company, setting the corporate direction, building a management team, and generallymaintaining a tight ship in a competitive industry.

Joe was responsible for all business development, from securingmillions of dollars in console and PC development deals to fostering major brand relationships with international companies like Hasbro and Playboy. Joe focused on becoming an expert on studio organization, personnel management, and communication systems, and has lectured on those subjects domestically and internationally.

Seth Spaulding: Describe your transition from a production position to a leadership position. What were some unexpected challenges or surprises?

Joe Minton: The transition was easier than I had expected as far as working with people in the company was concerned. Being an executive producer requires a lot of the same skills and internal relationships as does the president position.

What was a surprise was realizing that the buck really did now stop with me. I could get advice and seek input, but at the end of the day, I was the buffer between the company and the board, between the business realities and the hopes and dreams of the studio employees, and between the practical needs of the company and the actual resources at hand. The job felt like a non-stop balancing act.

The way I approached the challenge was to be as open and candid as possible to both the board and the employees of the company. For the company, we instituted an "open book" policy regarding the financial aspects of the business so every employee could see the effects of things like missed milestone payments on the company's overall financial picture.

Some in management thought this would be too much information for the average employee to handle effectively, and that it might upset them or cause undo concern. In some cases, it required additional discussions to allay concerns; however, overall the effect on the company was very positive and built a lot of commitment and trust among the employees. We usually presented the financials at the end of every quarter, and we also included projections looking out about a year. The projections included Best Case, Most Likely Case, and Worst Case scenarios.

Communication to the board was handled with the same candor, openness -- and even bluntness where appropriate to accurately describe and highlight key issues and in particular challenges in the coming quarter or year.

S.S.: Looking back, are there any decisions or practices you would change, and if so, why?

J.M.: I would insist on a clear written agreement between all significant shareholders on how key aspects of the ownership role would be handled, such as exit plans, personal guarantees, level of acceptable risk, short-term goals, and longterm goals. If the owners are not in perfect alignment, the business never can be.

The people who are in leadership seats at a twelve-person company are not likely to be the same people you want in those seats when the company grows larger. But they remain in those seats at a lot of companies to the detriment of the company and, ultimately, the careers of those individuals. The people in roles need to change to make sure their skills and contributions are best aligned with what the company needs from them to be successful.

S.S.: What is the most important thing you would tell someone making that transition within their company?

J.M.: You can (and I believe should) be friendly with people, but you cannot retain close friendships with people who you need to lead. You can pretend that you are able to, but when you control their livelihood, it simply is not a workable dynamic. It is best to embrace your new role fully or not to enter it at all.

A company leader has to be able to make very tough decisions that have very large ramifications on the lives of individuals. If you are not willing to do this with clear eyes on what will make the company stronger (thus ultimately helping the most people), you will not succeed as a leader. This doesn't mean you need to be cold, or that you should hide your agendas -- just that there is a difference between "friendly" and "friendship," and it is important to realize the distinction early.

S.S.: Were there any people who helped, and if so how?

J.M.: Other leaders in the company helped. Otherwise, finding people in similar roles in other companies -- even ones in vastly different fields -- was beneficial simply to understand what most everyone had to deal with and what was more specific to my situation. I found it very helpful to just have a safe and confidential environment where I could bounce ideas, vent, whatever, and not worry at all about the effect on the company.

S.S.: What are the most common traits shared by other effective leaders in your experience?

J.M.: Openness, communication, trustworthiness, integrity, ability to motivate, willingness to take measured risks, not procrastinating, understanding that being in charge doesn't mean being the expert.

S.S.: Which traits do you feel are your strongest and how does knowledge of these traits affect how you approach leadership challenges?

J.M.: Getting people to work in a common direction, and openness. I prefer employing everyone to help move the company in a particular direction instead of trying to do it all myself.

S.S.: What are the worst traits a leader has exhibited in your experience?

J.M.: Randomness, thinking one is the expert on everything, being wishy-washy, weak willed, easily overwhelmed, operating from fear, pretending to be a celebrity.

S.S.: How did these traits manifest themselves, and what was the result of their involvement in terms of the team, project, and/or company?

J.M.: Having a leader who is not consistent and who does not articulate where the company is going causes constant problems with direction and morale. People will not do their best because they have no clear goal in front of them, or, worse yet, will look to leave.

S.S.: Are there any leadership traits you admire or perhaps aspire toward but don't feel you embody? If so, how do you feel embodying these traits would make you a better leader? Do you consciously try to develop these traits? Do you mentor other leaders?

J.M.: Greater sense of being proactive on the large scale decisions that can dramatically affect the success of the company. I am attempting to develop this. I do mentor other leaders, usually by modeling behavior.

S.S.: Do you have any training in leadership, either formal or unstructured (e.g., armed forces experience)? If relevant, in what ways do you apply that training to challenges in your job?

J.M.: No.

S.S.: What do you see as the toughest challenge facing leads during a gamedevelopment project cycle or at a game-development company generally? How have you seen this handled most and least effectively?

J.M.: Leads generally are great at their discipline, and very often people who are great at their discipline are not great at leading people. They are two very different skill sets, and it is simply random as to whether someone has both -- having one is not a predilection toward the other. In the worst case, new leads are thrown onto a team and expected to know how to communicate, how to run meetings, how to motivate, how to effectively discipline, how to appropriately filter information from a publisher, etc. It can work well to make them a sub-lead first, or a lead on a small project with experienced leads as mentors.

S.S.: What are some common mistakes you've seen leads make, be they new or experienced?

J.M.: Most commonly, it is speaking for the people on their team without getting input. For example, deciding on schedules without talking to the people actually doing the work. This destroys morale and breeds friction as each party will blame the other when the project runs late, but the lead may not hear it publicly due to the employee's concern for his or her job. The very most important thing for a new lead to learn is how to communicate, listen, and to make informed decisions that build teams and do not destroy them.

Many new leads struggle with how much they need to command versus listen, communicate, collaborate, and guide. New leads sometimes need a lot of mentoring on this point from more experienced managers. It is common for a lead to think that this means "telling people what to do" when in fact it is a lot more about listening.

S.S.: How have you seen new leads best get support from directors or executives?

J.M.: Mentoring. Sometimes skill seminars, but I'm not sure how well these work.

S.S.: Do you think good leaders can be trained? Or is the essence of a good leader simply innate ability?

J.M.: It is innate, but can be trained from there. Some people are not leaders and will never be leaders. A slim few are innately good right away. More commonly, people have the ability but it has to be developed, trained, and practiced -- like pretty much every other skill you can think of.

[For those looking for more information on the book, we note that friend of Gamasutra and industry worker Mark Cooke has recently reviewed Team Leadership In The Game Industry.]

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author

You May Also Like