Are video games underpriced?

The objective of this article is to discuss if modern games are underpriced or overpriced, and how publishers and developers

Disclaimer: The gaming industry is global, but to make it simpler I will only use US figures. This simplification does not detract from the arguments in the article. Indeed, it should be straightforward to generalize them to a different regional market within the video game industry.

There is an intense debate in the gaming community at the time of writing over the price of AAA games, which has been stable at the %50 - $60 range for more than two decades. In those two decades, the gaming industry and the economy have changed considerably, and even our expectation as gamers of what an AAA game should be has grown.

Those that believe that games are underpriced point out at increasing development costs, studio closures, and the cumulative effect of inflation as critical signals that the industry needs to raise revenues to survive. Indeed, the rise of microtransactions as a source of income is seen by many financial analysts and gamers as both a proof and a sign that the industry should raise prices.

An example of this KeyBanc Capital Markets Analyst Evan Wingren wrote: "Gamers aren't overcharged, they're undercharged (and we're gamers) …” And “If you take a step back and look at the data, an hour of video game content is still one of the cheapest forms of entertainment," he wrote. "Quantitative analysis shows that video game publishers are actually charging gamers at a relatively inexpensive rate, and should probably raise prices." [1]

On the other hand, those who argue that games are overpriced mention the decrease of publishing costs, the emergence of the budget-priced or free hit, and the growth of the industry. The former is evidenced by the move to digital distribution, which is far cheaper than the physical retail box of old. The second refers to mostly to a few, highly successful, games on traditional platforms and mobile. Finally, the latter is based on the explosive growth of the market for video games - video game content spend in the US alone went from $17.5 Billion in 2010 to $24.5 Billion in 2016 [2]

The Key aspect of this debate seems to be if these factors are on the net beneficial for the industry or not. If the industry benefited then they should lower prices (but they won’t because they are greedy corporations, or so the overpriced proponents say). If the industry did not benefit, then it should increase prices to maintain healthy margins.

The Truth

I personally find the above discussion to be fascinating and will admit to having jumped in several times to debate it with friends and strangers. However, it is largely irrelevant, as the conversation assumes that the industry uses cost-plus pricing – a pricing strategy where the selling price is determined by the cost plus a “markup.” Instead, most of the gaming and traditional entertainment industry use value pricing.

In value pricing, the production cost of an item is irrelevant to its value. This strategy makes sense, your interest in playing a game is not influenced by how much the developer spent creating it as much as in how appealing is the content. Thus, it is up to every potential consumer to decide how much they are willing to pay for a particular game.

Therefore, the truth is that whether you believe games are overpriced, underpriced, or just right, you are correct.

How value pricing works

The central concept of value pricing is the willingness to pay (WP), by aggregating all interested gamers we can get an idea of what is the best retail price for a game.

Let’s start with an easy example consisting of only three potential buyers:

Gamer A loves the game and wants to support the developers by buying at $100

Gamer A loves the game and wants to support the developers by buying at $100

Gamer B is also excited and has pre-orded at the regular price of $60

Gamer C is not willing to pay more than $20

Gamer C is not willing to pay more than $20

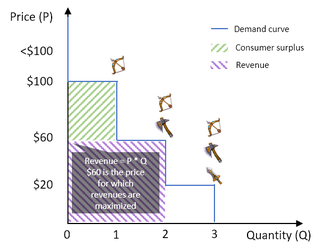

With this information we can create a simple "demand curve".

Sales revenue is calculated as Price x Quantity. Thus, the best outcome for the developer/publisher in this scenario is at $60. At that price point, Gamer A experiences what it is called “Consumer surplus” (CP), the benefit of buying something for less than what it was prepared to pay, for this person the game is clearly underpriced. Conversely, Gamer C will stay clear of the game.

Sales revenue is calculated as Price x Quantity. Thus, the best outcome for the developer/publisher in this scenario is at $60. At that price point, Gamer A experiences what it is called “Consumer surplus” (CP), the benefit of buying something for less than what it was prepared to pay, for this person the game is clearly underpriced. Conversely, Gamer C will stay clear of the game.

There is no benefit to the developers to lower the price enough so that Gamer C can buy it – at least not initially, as we will discuss later.

This example, though simple, is representative of the AAA game industry. The consensus is that lowering the price so that the Gamer C crowd joins in during the first few months is not worth it for both financial and psychological reasons. Financially, the lost revenue from charging less to the Gamer A and Gamer B groups is not offset by extra sales to Gamer C.

Psychologically, Gamer C is a “bargain hunter,” they are more likely to spend $20 for a $60 game on sale than $20 on a non-discounted game – If you are interested in a real-world example of bargain hunting check JC Penney’s failed experiment in retail https://hbr.org/2012/05/can-there-ever-be-a-fair-price

Price discrimination & Behavioral economics

Selecting the correct retail price is crucial to the financial success of both developer and publisher. However, it is possible to “capture even more value” (i.e., revenue from gamers) by employing a sort of third-degree price discrimination.

Price discrimination is a pricing strategy that charges different customers different prices for virtually the same product or service. There are three kinds of price discrimination:

First-degree price discrimination: The company charges every consumer its full WP. This scenario is uncommon in real life, not only would the company need to mind read each person’s WP, but the legality of charging seemingly arbitrary amounts to consumers up front it is questionable. Nonetheless, there are some companies currently experimenting with using behavioral data and AI to identify a particular consumer WP and we might start seeing this more often.

Second-degree price discrimination: The company charges consumers different prices depending on the number of units they buy, this is bulk pricing. This scenario is typical in many industries, but the gaming industry is not one of those – Gamers are unlikely to have a reason to buy several copies of the same game.

Third-degree price discrimination: The company segments the market into groups of consumers and charges each group a different price. The classic example of this scenario is students and the general public at the movies – Students are encouraged to self-identify as such and get a discount, while adults pay a full price.

In textbook third-degree price discrimination, the product is the same for all consumers, this is not true in our example, as Gamer A is receiving extra content. The reason for the additional content is psychological: Gamer A was willing to pay extra for the original game, but setting the retail price below its WP has “anchored” it (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anchoring), and it is no longer willing to pay above the “fair” price. Therefore, the publisher slaps on an amount of extra content to give Gamer A an excuse to pay more, the actual value of the extra content is not too relevant and can vary greatly between games. The rationale for this comes from Behavioral economics, and while it might seem as if the publisher is taking advantage of the consumer, it is, in fact, a win-win situation. Consider that Gamer A was already willing to spend more than retail for the base game, with a “deluxe edition” Gamer A is getting a better deal (more content for a similar price).

The game industry has specific qualities that facilitate third-degree price and behavioral discrimination:

Identifiable consumer segments with different WP and willing to self-identify: In our case Gamer A, Gamer B will naturally buy the deluxe and retail edition, respectively, in the first six months of a release. Gamer C will buy later when the game goes on sale. There is no drawback or stigma associated with any of these groups

Negligible marginal cost of an extra unit: digital nature of the industry means that the cost of selling one additional copy is insignificant for most games

Negligible cost of bundling extra content: Most deluxe versions include material that was produced to make the game, printing a concept art book or providing the game’s soundtrack is minimal

Ease of adding new content: it is relatively straightforward to provide extra content to paying gamers, this is relevant for specific game promotions that include the next X DLC for free. A recent example is the Civilization VI Digital Deluxe edition that included the upcoming six DLC packs to be released

Market separation: It is unlikely that an entity will be able to buy on sale and then resale for Gamer B (retail) or Gamer B (deluxe) price point. This is mostly because Gamer B and A value buying the game near release date (Time separation)

Monopoly/Brand Power: There are many games out there, but the best games create the illusion of uniqueness through gameplay or marketing. In a sense, there is no adequate Civilization substitute for Gamer A and Gamer B at the time of release

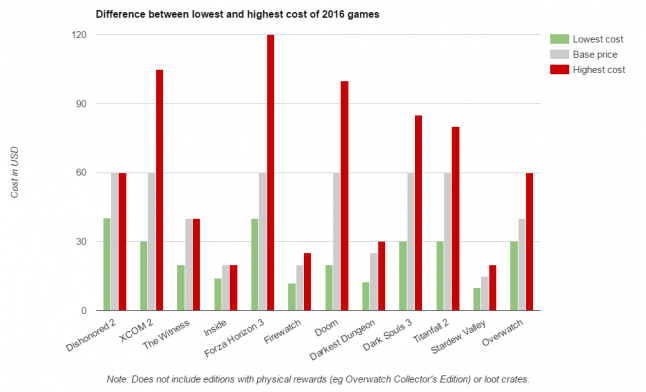

The extent of price discrimination in the industry is evident when looking at the following graph of 2016 sales for the 11 top rated games by PCGamer magazine:

What about micro-transactions and loot boxes?

For a sizable proportion of gamers, the question “are video games underpriced?” is actually “will an upfront increase in price prevent us from seeing loot boxes?”. The answer to that last question is no. Publishers and developer, as corporate entities, have a responsibility to monetize as much as possible the value they are creating. If you think that profit maximization is evil, do think that it is likely that you are benefiting from it as an indirect owner of EA, Activision Blizzard, etc.. through your retirement plan or insurance policy. Society benefits from responsible profit generation.

The introduction of loot boxes everywhere is the natural result of positive feedback (in the form of increased revenue) from gamers in sport and mobile games over an extended period. The community outrage is signaling to the game industry that there is a group of gamers for which that kind of monetization (loot boxes) is not acceptable and that the monetization technique is in detriment to the experience (gamer’s WP is reduced for current and future games). Publishers are not deaf, and in the long run, they will follow what (most) gamers want.

If you are one of those persons who oppose loot boxes, do reach out to publishers/developers and other gamers, organize and communicate assertively. Any discussion over price, it’s a distraction.

This post was first published at my blog http://leonardperez.net/ , where I will talk about production and the game industry.

[2] http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/!EF2017_Design_FinalDigital.pdf

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)