Virtualization: It's Faster Than You Think.

Virtualization is a hot trend in the general computing and IT worlds, but hasn't seen much action in game development. Let's take a look at the performance of a modern virtualization solution to see if VMs really are too slow for game developers.

As developers and as gamers, we can be a bit obsessive about performance. Usually, this works to our advantage, but it can also obscure perfectly good solutions to some of the challenges of game development.

One of these overlooked gems is virtualization (even more background here). Many of the benefits derived from running software on virtual machines come from their portability. When you set up a virtual machine with the OS and applications all properly configured, you end up with a complete, self-contained software package. It becomes easy to do things like back up that whole system, distribute it to your teammates, move it to new hardware, and even roll back to previous configurations. If you do it right, you'll never have to reinstall those apps again - more time programming, less doing IT!

Figure 1

A potential drawback to virtualization is that you only get limited access to some kinds of specialized hardware, including GPUs (although this is changing). The other detractor from a game developer's perspective is the performance cost. However, the performance penalty is not as high as I first thought.From a qualitative perspective, if you can look past the slow video (which is typically better than a remote desktop, but still noticeably slower than native) the overall system performance is fine for a lot of things. You can do standard desktop tasks like web browsing, email, and word processing normally. This is handy if say, you want to give everyone a standard office-software setup without passing a stack of install disks around the office.

Maybe more useful though, you can run most server and batch processes perfectly well on a VM. After all, these kinds of applications generally don't require any video output. Centralized services like this are also where reliability and disaster recovery are valued the most, since the whole studio can potentially be interrupted by any down-time in the server room (or closet, or space-under-your-desk, depending on the size of the IT budget).

Getting back to the performance discussion, I've claimed that performance is decent on VMs, so how about some numbers to back that up? To get some quantitative stats, I used some freely available benchmarks. I ran the tests on my desktop (a mid-range quad-core system) natively, and then with VirtualBox. There was no careful scientific protocol involved, I just ran the tests as they come out of the box, on a VM with default settings. The numbers were surprising.

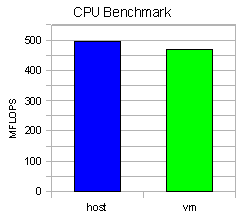

The CPU benchmark showed the VM running at 95% of the speed of the host machine (see CPU Benchmark). The memory benchmark was about the same. Where the VM was weak was disk I/O, which was around 70% of the native speed (see I/O Benchmarks). Not terrible, but enough to make you think twice about doing something I/O intensive like a high-end database server. That said, this was a simple out-of-the-box test, most virtualization hosts have options to enable better disk performance.

These are synthetic benchmarks, not numbers generated from real world applications. You can probably find some real world benchmarks comparing VMs to native machines for things like web servers, but what about something more specific to games?

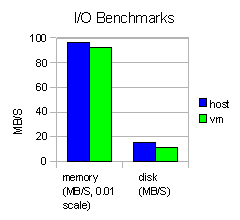

First I tried a rendering test using YafaRay to render a couple of sample scenes. The results were amazing - there was almost no difference in the render times, (check out Rendering Benchmarks). The big test though was compiling code.

First I tried a rendering test using YafaRay to render a couple of sample scenes. The results were amazing - there was almost no difference in the render times, (check out Rendering Benchmarks). The big test though was compiling code.

I grabbed the GPL-ed source for Quake 3, and a copy of Ogre3D for these tests. Here, the VM stumbled a bit. On both codebases, compile times were almost 55% higher (see Compile Benchmarks) on the VM. Now, to put that in perspective, for Quake 3 that added about 25 seconds to the build time, which probably wouldn't bother anyone on a build server. Ogre3D on the other hand is a long build (almost 15 minutes) made longer by the VM (over 20 minutes). Often, build times are dominated by disk I/O, (accessing headers and reading/writing intermediate files), which is consistent with the 1 GB (!) of intermediate files produced by an Orgre3D build.

Overall, virtual machines provide a surprisingly capable platform. In fact, for pure number crunching (CPU and memory) you're only paying a tiny penalty for the conveniences provided by the VM. If you are I/O bound, things aren't quite as cut-and-dry, but still worth considering. For example, if you want to set up a build server on a VM or virtualize your development environment, you'll want look into the disk optimization features of the virtualization host. For much of what we do with our computers though, we don't actually max out the performance of the hardware (at least not for very long), so the VM overhead is not a big factor.

If you want to try some of this out for yourself, two of the big players right now are VMware and VirtualBox. I've tried products from both, and they're all pretty solid. VMware offers elaborate management tools for large scale deployment and disaster recovery. VirtualBox on the other hand has an open source edition, which has led to some interesting developments like virtual D3D support.

Virtualization can't replace native machines (yet) for high-end 3D work like DCC and running modern 3D games, but for almost everything else, it makes a compelling case. The time saved from redundant reinstallation and reconfiguration of software leaves more time for game development and really, who doesn't want more time?

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)