Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Reinventing the wheel

In this entry I explain the motivation behind the decision of making our own engine for our first video game, Psychotic's MechaNika.

It is said that reinventing the wheel is stupid. Personally, and taking into account some nuances, I see at least two cases where it would be justified. First, a wheel with a design that has some requirements that are not fulfilled by the existing alternatives. If such design (or the designer) is not flexible enough there is no choice but creating a new wheel, the innovative wheel. Second, when the required wheel is not different from existing ones. In that case, knowing the details behind the building of the wheel and being exposed to problems that others solved during the process can suppose a challenge interesting enough to reinvent the wheel, the educational wheel.

At Mango Protocol we have created our own adventure engine, basically due to the two previous motivations. On one side, after an analysis phase when we studied some of the available options, we concluded that, or they did not provide all the features we needed, or they were not properly documented, because of the lack of documentation itself or because we did not find games similar to our project built using these tools. Moreover, I, being the programmer in the studio, found interesting to create our own engine for the adventure game we were designing and, thus, face a new challenge.

Our game, MechaNika, is not going to make a revolution in the adventure games world regarding the genre basics. It has dialogues, inventory, it follows the classic rules of point and click adventures, and the player has to interact with the environment and the entities that wander around in order to solve the different puzzles. But we had some design ideas that did not want to give up because of choosing an engine with certain limitations. Some examples are our dialogue system, the player interaction handling during the resolution of some puzzles, or the possibility to offer the game in different platforms.

As a result, after studying some alternatives, including specific tools for adventure games development like Visionaire Studio, Adventure Game Studio and Wintermute Engine, generalist engines like Unity 3D, Construct 2 and Stencyl, and frameworks like cocos2d-x and libGDX, we chose the latter one. The main reasons for the given election are due to the definition of libGDX itself: it is a framework for multiplatform video game development using the Java programming language. Being a framework instead of an engine it does not offer entities that can be used out of the box in a video game, but it offers a set of subentities that, together as attributes and properly wrapped, allow to create any entity the developer needs. Moreover, the given abstraction layers allow to easily use some systems like the graphics and sound ones. This makes the programming more versatile but also requires the related design to be more detailed. Being multiplatform, specifically for Windows, Linux, Mac, iOS, Android, Blackberry and HTML5, it clearly increases the chances of bringing the game to any of these platforms, and really easily. Last, using Java as the programming language, which I have been happily using for a long time during my work as software engineer (not kidding), granted a learning curve with a steep start.

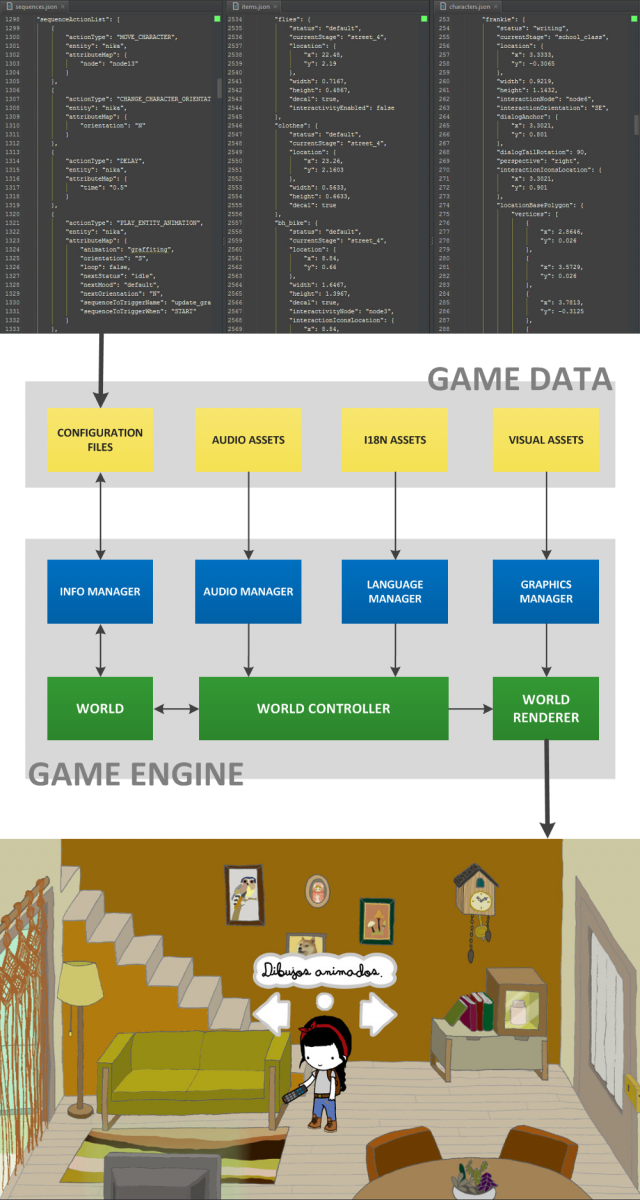

Once the tool to move MechaNika was confirmed it was time to design the engine. First it was considered to be built just for that specific game according to the project requirements, but then arose the idea of having an engine that would be independent of certain elements. Such idea considered making more adventure games in the future using the same engine and just having a set of external configuration files. Thus, create an engine that implemented the game management in terms of graphics, audio, navigation, entities, inventory, actions and a bit more. The characters, items, stages and their gates, world variables, puzzles and dialogue tree would be defined in JSON files that would feed the engine, where everything would come to life. Even a visual edition tool could be created in order to ease the generation of these configuration files, including the processes of assigning attributes to the different entities, the dependency chain related to a puzzle resolution, and drawing the cells, nodes and gates for the navigation mesh of any stage, for example, then allowing to export such configuration to the corresponding files. It is rather unlikely that this editor will be created or the engine will be used for a new game after MechaNika is finished, because we have many more game ideas in mind that are not adventure games, but the premise of designing a black box that builds games of this kind from configuration files is still valid for the creation of a modular and extensible engine, granting a less painful development process.

After some months of development and close to finishing the game, the engine is very modular, allows to be easily extended, and, although documentation is really scarce, revisiting an old method does not mean opening Pandora’s box thanks to the thorough API design. It is not as nice and well done as I would like it to be, but this is life and sometimes priorities and restrictions appear and you just can not ignore them. However, the experience has been really enriching, and experiencing how easy is now to add stages, characters, items or to define puzzles and related interactions, just adding little blocks of parameters to the appropriate files and following the required naming conventions, is also very rewarding.

It is my wheel. Innovative and educational.

Reinventing the wheel

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)