Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Games developers may be unhappy with Unity’s growing focus on monetization rather than creation, but ultimately this is the only proven model for funding high levels of investment in development tools.

Unity announced on July 13th that it was merging with Israeli adtech specialist IronSource. The deal, valuing IronSource at $4.4bn, will see it become a wholly owned subsidiary of Unity with existing IronSource shareholders owning 26.5% of the combined company. Though Unity has made a number of high-profile acquisitions in recent years, this deal is unprecedented in both in size and its implications for Unity as a company, and the broader games tech ecosystem, of which Unity is a key pillar.

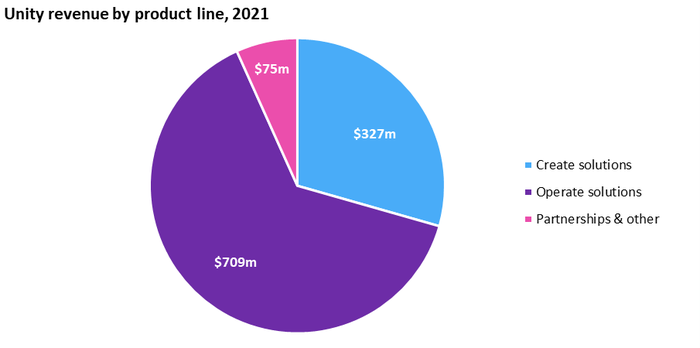

Though best known for its game engine, Unity has for several years earned most of its revenue from advertising. 64% of Unity’s revenue in 2021 came from ‘Operate’ solutions, the vast majority of which comes from the company’s ad network. ‘Create’ solutions – the game engine business – accounted for just 29% of revenue. This reflects a broader trend seen by many games tech vendors: it’s easier to monetize monetization. Solutions not directly tied to monetization – even those as critical as game engines – tend to be perceived as costs to be minimized. Whereas direct monetization solutions with revenue share models more obviously “pay for themselves” and scale much more easily.

Figure 1: Unity makes most of its revenue from Operate solutions – largely advertising

With the IronSource deal, Unity is doubling down on its role as a monetization business – and specifically an ad monetization business. Both Unity and IronSource have ad networks which are prominent in the mobile games space but not in the top tier of ad networks generally. Merging these networks will has the potential to create a genuine top tier player rivaling the likes of Google and Facebook, at least in the games segment. IronSource also has a richer range of supporting technology, critically including ad mediation, which combines access to multiple ad networks in a single SDK integration (a capability Unity previously lacked).

Among developers, a sense was already brewing that Unity had lost focus on its game engine and was distracted by its ad business and ventures into non-gaming sectors. The news that Unity was pouring billions of dollars into an adtech acquisition was therefore always likely to go down badly, particularly coming just two weeks after Unity announced substantial layoffs. Add to the mix IronSource’s past association with a malware installer, and some extremely ill-judged comments from Unity CEO John Riccitiello disparaging developers, and the result was serious backlash.

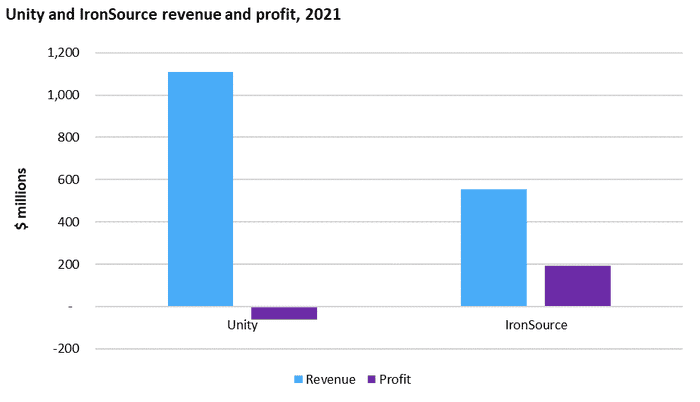

But while the immediate discontent will surely blow over (and in any case the indie developers taking the most vocal anti-Unity stances contribute very little to the company’s earnings), the ill-feeling among developers does point to deeper issues. Unity has poured vast resources into developing its game engine, losing money every year since its foundation. Yet it finds itself generating most of its revenue not from its engine but from advertising. True, the Unity game engine was the platform that drove adoption of its ad network, but even that was never enough to break even overall. Indeed, part of the rationale for the IronSource deal is that undoubtedly that IronSource, which is profitable, will help to stop the combined company hemorrhaging cash with the era of cheap money apparently at an end.

Figure 2: IronSource should be profitable enough to offset Unity’s losses

If Unity can shore up its profitability only by leaning ever harder into advertising, that poses wider for the games tech market. In recent years the games industry has been moving away from reliance on in-house tools and towards open source and, especially, paid external solutions. The share of games developed on in-house engines compared to Unity and Unreal Engine has been dropping steadily, while external solutions for everything from analytics to matchmaking are replacing internally developed tools. But how sustainable is this trend if truly profitable, scalable businesses only seem to be possible right at the point of monetization?

In Unity’s case, perhaps the synergy between its game engine and its ad business is sufficiently strong to continue pouring resources into the engine as the platform on which its monetization solutions sit. But most other companies are not into the same position. Epic Games has invested a large part of its Fortnite riches into Unreal Engine for quite meagre returns so far. Like Unity, it has a suite of services attached to its engine, but unlike Unity it lacks advertising or other significant monetization tools. For Epic, but also for emerging vendors like Pragma and Incredibuild which are building tools for development and operations, it remains a key and unanswered question whether these can be made into a highly scalable, profitable businesses.

Games developers may be unhappy with Unity’s growing focus on monetization rather than creation, but ultimately this is the only proven model for funding high levels of investment in development tools. Ultimately, if developers want to continue taking increasing advantage of solutions that free them from the burden of building their tools in house, the only options are to accept that these will likely come with a heavy emphasis on monetization, or to start paying more for these solutions directly.

You May Also Like