The game world is violent, I must be careful who to trust

Two studies investigate the psychological processes underlying short- and long-term effects of video game violence on interpersonal trust.

The study was presented during ICA 2014 annual meeting by the fourth author, Christoph Klimmt (Hanover University of Music, Drama and Media).

Tobias Rothmund (University of Koblenz-Landau), Mario Gollwitzer (Philipps University Marburg), Jens Bender (University of Koblenz-Landau) and Christoph Klimmt published this study in Media Psychology. The study is also continuation of their previous study published in 2011 of which I have previously blogged on.

Abstract

Two studies investigate the psychological processes underlying short- and long-term effects of video game violence on interpersonal trust. Study 1 demonstrates that interacting with physically aggressive virtual agents decreases players’ trust in subsequent interactions. This effect was stronger for players who were dispositionally sensitive to victimization. In Study 2, long-term effects of adolescents’ frequent exposure to video game violence on interpersonal trust and victim sensitivity were investigated. Cross-lagged path analyses show that the reported frequency of playing violent video games reduced interpersonal trust over a period of 12 months, particularly among victim-sensitive players. These findings are in line with the sensitivity to mean intentions (SeMI) model, and they suggest that interpersonal mistrust is a relevant long-term outcome of frequent exposure to video game violence.

This blog post is cross-posted at VG Researcher.

The theoretical basis for this study is the Sensitivity to Mean Intentions model (SeMI; see Gollwitzer et al., 2013). The model posits that people are suspicious, mistrustful and less willing to cooperate in uncertain social situations from the interaction of two factors. The first factor is personality disposition and relevant to SeMI is a person’s victim sensitivity, that is one’s sensitivity to situational cues of untrustworthiness (e.g. “I can’t easily bear it when others profit unilaterally from me”). The second factor is those situational cues of untrustworthiness and exploitation (e.g. social loafers who are rewarded despite not contributing). With the presence of these factors, this would evoke a state of suspiciousness which can bring immoral and aggressive thoughts into consciousness. This in turn brings out behaviours that guards against being exploited, this includes aggressive behaviours.

Study 1

They conducted an experiment to examine short-term causal effects of playing a violent videogame and its subsequent effect on interpersonal trust in a trust game.

Method

Participants: 84 German male high school and undergraduate students. Average age is 23.5, SD = 4.5).

Measures

Victim Sensitivity: The Justice Sensitivity Inventory. It is a 10-item answered on 6-point scale. An example is “It burdens me to be criticized for things that are overlooked with others.”

Videogame used: A modded version of Half-Life 2. With the help of the department of simulation and graphics at the Otto-von-Guericke University Madgedeburg, they were able to construct three scenarios.

The premise is that Gordon Freeman is tasked to rescue Barney who has information about the Combine. Gordon reached General Taggert’s hideout who knows where Barney is and the general will ask Gordon of something. Gordon is then tasked to find some piece of equipment in an old coal mine.

Scenario 1 (Social betrayal and physical aggression): General Taggert wants Gordon to fight his strongest soldier with metal tubes (no crowbars?) before he tells where Barney is. The soldier cheated as he used smoke bombs which was against the rules as announced by Taggert. Afterwards, Gordon has to fight the combine in the coal mine to retrieve the equipment, but his ally was actually a Combine spy and attacked him.

Scenario 2 (Physical aggression): General Taggert wants Gordon to fight his strongest soldier with metal tubes before he tells where Barney is. Afterwards, Gordon has to fight the Combine in the coal mine to retrieve the equipment.

Scenario 3 (control): General Taggert wants Gordon to win a racing duel before he tells where Barney is. Gordon had to go to the coal mine and retrieved the equipment without incident.

Playtime for these scenarios is 25 minutes.

Interpersonal trust: To assess interpersonal trust after videogame play, participants played a game of trust. This trust game involves the participant transferring amounts of money (up to 2 Euros) to another person. The transferred amount’s value is then tripled. This other person could then keep the money or share it. The trust game is set up in a way that the truster’s motivation is based on the fear of being exploited rather than greed. The participants were actually told the their positions were randomly assigned and they are dealing with another unseen participant.

The amount of money the participant chose to give to the other participant is used to assess interpersonal trust.

Procedure

A week before the experiment, participants completed the victim sensitivity scale. Participants were tested individually and were randomly assigned to one of the three scenarios in the videogame. Afterwards, they completed the trust game and were asked questions about the videogame in order to see if the experimental conditions were done right, and it was.

Results

The authors conducted a one-way ANOVA examine whether there are differences in the amount of money given depending on the three scenarios. Participants who were in the betrayal condition were less trusting of their partner in the trust game in that they gave 1.402 Euros on average than those in the control condition who gave 1.738 Euros on average. Those in the aggression condition were also less trusting who gave an average of 1.296 Euros, they were statistically indistinguishable from the betrayal group, but are statistically different from the control condition.

The authors conducted another analysis examining how participants’ victim sensitivity might play as a moderator role between the relationship. They found those with high victim sensitivity (above 1 standard deviation over the mean) were much less trusting when they played the aggression or betrayal condition than those with low victim sensitivity and those played the control condition.

Study 2

They conducted a two-year longitudinal survey of German adolescents to investigate the long-term effects on interpersonal trust from playing violent videogames. This is to complement their experimental findings into more ecological valid environment.

Participants: 759 German adolescents, 45% boys and 44% girls and the rest who did not disclose their gender. At Time 1, the average age was 14.17 (SD = 1.11) and the participants were in their 7th, 8th or 9th grade.. At Time 2 which was 12 months later of Time 1, participants were called again and they authors managed they get 582, 44% boys and 46% girls and the rest who did not disclose their gender.

Measures

Violent videogame exposure: Participants were asked three questions: How many days they usually play videogames per week and how many hours they usually play during the day. They were also given a list of 40 games that were popular in the second half of 2008. Participants were asked if they played each list game in the past year. Some of the listed games are Age of Empires, Assassin’s Creed, Bioshock, Black & White, Diablo, Counterstrike, Doom, Final Fantasy, Grand Theft Auto, Guild Wars, Halo, Half-Life, Jedi Knight, Need for Speed, Quake, Resident Evil, Unreal, Warcraft, World of Warcraft. I hope the survey was conducted during 2008-2009 because that list gets outdated pretty quickly, much like the blockbluster list of movies.

Interpersonal trust: The German translation of the General Trust Scale. A 6-item answered on a 5-point agreement scale. Example item include “Most people are trustworthy”.

Victim sensitivity: The short-version of the Justice Sensitivity Inventory. A 5-item answered on a 6-point scale.

Results

A repeated measure ANOVA was in order to examine changes over 1 year period. The factors were gender by grade, and time. The results revealed that boys played more videogames from Time 1 to Time 2, whereas girls do not. Victim sensitivity did not change across time, but a significant change for interpersonal trust where those in the 8th and 9th grade at Time 2 reported less interpersonal trust than at Time 1.

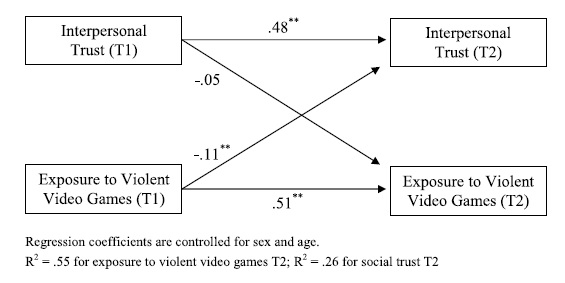

With these results in mind, they conducted cross-lagged path analyses examining the effects of violent videogame exposure over time with grade and gender as control variables.

The graph shows that interpersonal trust at Time 2 decreased as a function of exposure to violent videogames at Time 1. Interpersonal trust at Time 1 did not affect violent videogame exposure at Time 2, but was predictive of interpersonal trust at Time 2 because they’re related.

Violent videogame exposure and victim sensitivity did not affect each other across time.

They further tested whether victim sensitivity acted as moderator in the relationship. The authors found that interpersonal trust at Time 1 was predicted by violent videogame exposure and interpersonal trust at Time 1 much similar to the graph above. More importantly, victim sensitivity moderated the relationship between violent videogame exposure at Time 1 and interpersonal trust at Time 2 in that this relationship applies for those with high victim sensitivity (1 SD above mean), but not for those with low victim sensitivity (1 SD below mean).

Discussion

The take home message from these studies is that violent videogame exposure lead to decreases of interpersonal trust of others. Within the laboratory setting, a recent aggressive episode, whether it involves a betrayal or violence, in a videogame led to decreased trust of another person in a single instance of a trust game. Moreover, the long-term indicate that violent videogame exposure predict a decrease in interpersonal trust in the future. There is a conditional factor from a person’s victim sensitivity. For those in the average, the relationship is true, the effect is stronger among those who scored high, but the relationship is not significant among those who scored low on victim sensitivity.

The authors argued that not everyone is affected by the same extent through playing violent videogames. According to the SeMI model, the studies do demonstrate that frequent exposure to cues of meanness and hostility would lead individuals to feel less trustful, less open and more cautious about other people in the real world. On the other hand, the authors offer directions for future studies that might clarify the relationship with videogames and interpersonal trust. First, the effects of prosocial and cooperative gaming might affect interpersonal trust. As players help each other out, they might build a trusting relationship with each other. Second, the effects of multiplayer gaming would mean an examination of interpersonal communication between players, that is both behavioural and verbal. It is possible that the effects they have found with NPCs would be stronger as players are interacting with each other as social and human beings.

There are multitude of implications from my perspective. As the authors mentioned about the multiplayer aspect of videogames, this would bring a lot of other interpersonal theories into play and that means we need to find some interpersonal communication scholars into gaming research. You know experts who study relationships, self-presentation and such. A possible relation with the study is Sarah Coyne and colleagues (2012) findings on videogames and couples conflict. Both share similarities about violent videogames effects on interpersonal hostility. At present, the SeMI model would be very useful to examine how trolling, player-killing, ninja looting, harassment and other uncooperative behaviours would affect players’ future interactions with other players. Would the frequency of such behaviours makes a player weary of other players and how they would cope with these behaviours, would they pre-empt potential mean players by doing the same behaviours on them? This could apply to sexual harassment as other players’ mean behaviours would make female players less trusting of other players, perhaps influencing their future interactions with others being more guarded and less self-disclosing about themselves, perhaps in-game and in real life.

Another implications draws from the bullying and cyberbullying literature. I am a bit sketchy in that area. I recall that being bullied would also lead to greater aggressive behaviours, some of which would mirror bullying behaviours, so a sort of perpetuating bullying. Although, their study examined interpersonal trust from a single behavioural measure, it would be interesting how interpersonal trust can be elicited in an antisocial manner.

A third implication is a sort of reversal of the SeMI model. As they mentioned prosocial videogames, cooperation and prosocial behaviours, it would be worthwhile to examine how players in online gaming settings form relationships, groups, building and maintaining interpersonal trust in various environments. Some research questions would be like what are the conditions that are favourable and unfavourable to building interpersonal trust? Videogame characteristics, such as unmoderated social environment, for example some FPS games, might be conducive for greater mistrust as players perceive such environment as a free-for-all and perhaps high-risk, if losing or dying is significant, think losing your hard-earned loot.

References

Coyne, S. M., Busby, D., Bushman, B. J., Gentile, D. A., Ridge, R., & Stockdale, L. (2012). Gaming in the game of love: Effects of video games on conflict in couples. Family Relations, 61 (3), 388-396. DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00712.x

Gollwitzer, M., Rothmund, T., & Süssenbach, P. (2013). The sensitivity to mean intentions (SeMI) model: Basic assumptions, recent findings, and potential avenues for future research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7 (7), 415-426. DOI: 10.1111/spc3.12041

Rothmund, T., Gollwitzer, M., Bender, J., & Klimmt, C. (2014). Short- and Long-Term effects of video game violence on interpersonal trust. Media Psychology, (pp. 1-28). DOI: 10.1080/15213269.2013.841526

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)