Storytelling in Games and Interactive Media. Chapter 7

Now that we have reviewed the literature in all kinds of aspects, let's finally move on to a more practical note!

Introduction

As we have seen, there are many methods of analysis and structuring, as well as varying responsibilities that might fall in the hands of the job title depending on the studio.

Now that we have reviewed the literature in all kinds of aspects, let's finally move on to a more practical note!

"Months ticket by, and patience wore thin as we argued

over style and anorexia and Angelina Jolie"

- The Art of Alice: Madness Returns

Defining the mood

A theme is the central topic of an artwork. Themes are usually abstract notions as opposed to the tangible plot topic. They describe what the game is about, what binds all components together. For example, we could argue that Black Desert is, at its core, a story about sacrifice in favor of power.

Figure 1: Black Desert Online. Pearl Abyss.

As with all branches of game design, communication is key. Creative director Mike Laidlaw breaks down the most important aspects to communicate clearly and briefly in his 2018 GDC talk. Those aspects should be defined early on, and be present throughout development for the whole team as a point of reference.

Next to themes, the second aspect is tentpoles. This notion refers to the plot moments that stand out, and are generally what marketing wants to put in the trailer, as well as serving as a reference for the team to focus on the moments that are "spectacular, emblematic, or evocative".

The third aspect mentioned by Laidlaw is character motivations. Why do the main characters care about the plot and story world, and with whom do they disagree?

The fourth and last aspect is elevator pitches. They serve as a quick way to explain why something is important, and, even if the game of feature is not going to be pitched to a publisher or investor, they serve as "a vision touchstone".

Weekes and Epler(2016) describe their iteration process on Dragon Age Inquisition: Trespasser as three-parted: Vision(the shared target), critique(get the content playable asap to evaluate it early on), and revision(how to get the content closer to the vision).

Vision starts with broad goals, that is, "The functional objectives that you need to accomplish over the course of the piece of content you're looking for". In the case of Trespasser, the first goal was to learn the truth about Solas while giving a sense of wonder about the world, and melancholy, as one of the closest allies so far maybe wouldn't be around anymore. Second, to show that the inquisition was infiltrated.

The second step within Vision is to find appropriate references. References, according to the speaker, need to comply with three characteristics. First, they need to be intuitive, meaning that it should be instantly understandable why they relate to the product. Second, they have to be inspirational. And third, "good" is optional, instead, they should focus on conveying the emotion.

In the case of Trespasser, references were "Truth behind Mythology"(seen as a theme of Indiana Jones), together with "the corruption of organization" from Captain America: Winter Soldier. That's the overall vision for the project, on a macro level. On a micro level, we can also part from there to set a vision for individual dialogs, dungeons, etc, which gives this consistency across content.

In The Art of Alice: Madness Returns, one of the artists gets interviewed regarding references and states that "Artists we found particularly inspiring included Dave McKean, Mark Ryden, and Zdzislaw Beksinski – but we drew from a wide variety of sources including cosplay, custom jewelry, collector's doll props, burning man art, and taxidermy. We also owe a lot to fantasy films like The neverending story, The Dark Crystal, Return to Oz, The City of Lost Children, and Pan's Labyrinth, as well as the work of the Creature Shop and the Brothers Quay."

Breaking Down

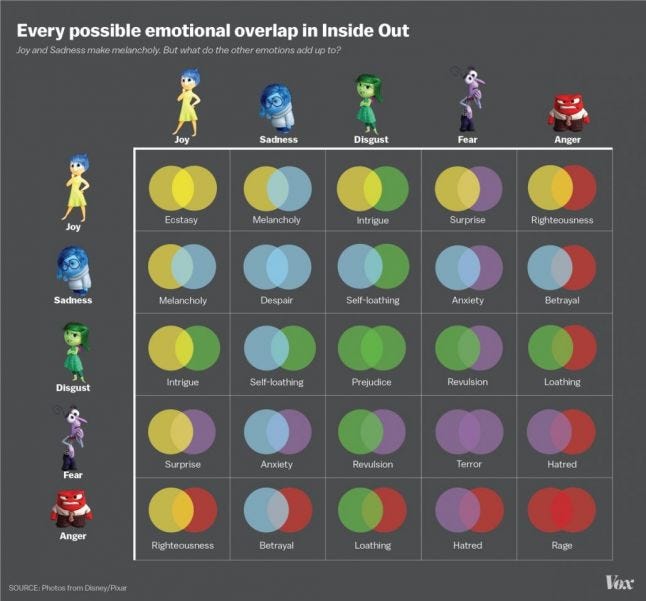

Mehrafrooz proposes to "just start our game narrative by trying to understand what kind of emotion or ideas we want to explore with the game."

This breaking down equals setting a theme, and can equally apply on a lower level to individual characters, zones, sequences, etc.

Figure 2: Mehrafrooz, B., (n.d.). The Ultimate Guide to Game Narrative Design. Pixune. https://pixune.com/game-narrative-developing-a-story-that-works/

Mehrafrooz argues that we can divide a story world into three sections, each of which can be treated individually regarding the narrative as a whole and the game's overall design: plot, character, and lore.

Figure 3: Mehrafrooz, B., (year unknown). The Ultimate Guide to Game Narrative Design. Pixune. https://pixune.com/game-narrative-developing-a-story-that-works/

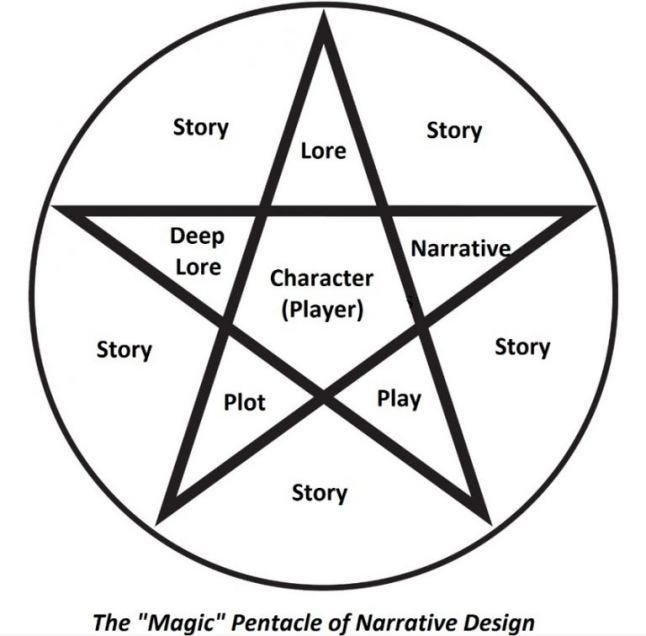

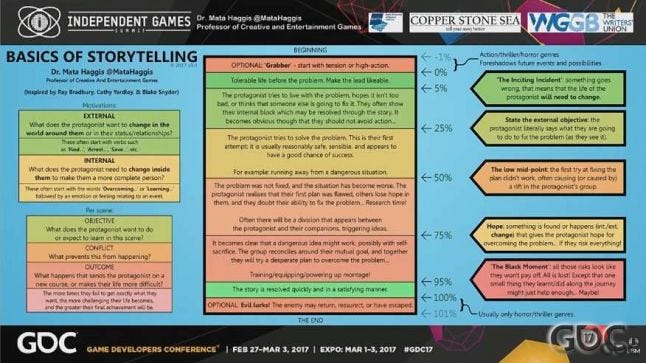

Apart from the many sequencing devices presented in the previous parts, one that resulted suiting to me, personally, is the framework provided by Mata Haggis in his 2017 GDC talk. Here, the story is ordered in a classical Aristotelian structure. Parting from the principal block, smaller blocks of the story may branch off following any framework, being ordered for example in a circular Monomyth shape or a maze or rhizome structure within the preferred software.

Popular tools for plot layout include Twine, InkleWriter, or Choicescript. Joseph Humfrey explains the ups and downsides of InkleWriter compared to the scripting language Ink in his GDC talk titled "Ink: Behind the Narrative Scripting Language of '80 Days' and 'Sorcery!'".

Figure 4: Haggis, M., (2017). Storytelling ools to Boost Your Indie Game's Narrative and Gameplay. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8fXE-E1hjKk

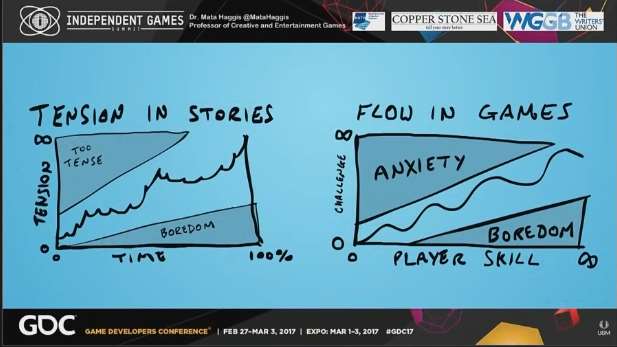

Haggis(2017) draws a connection between gameplay flow and story tension. Similarly, at BioWare story tension is sequenced episodically on a graph, as Epler(2016) explains.

Figure 5: Haggis, M., (2017). Storytelling ools to Boost Your Indie Game's Narrative and Gameplay. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8fXE-E1hjKk

Figure 6: Weekes, P., Epler, J., (2016). Dragon Age Inquisition: Trespasser – Building to an Emotional Theme. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ao4b4aN7RgE

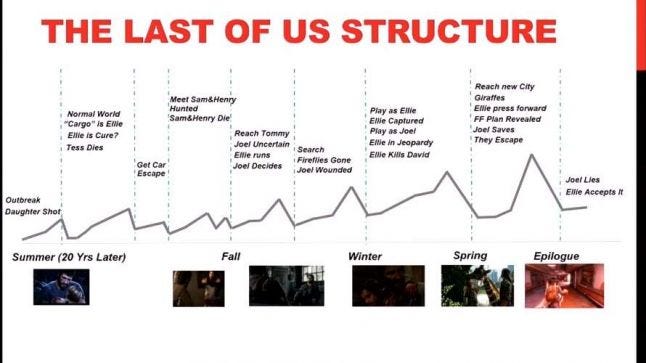

Plot sequencing in The Last Of Us took the form of a "serialized TV story", as Richard Rouse III(2014) explains. While it was not released episodically, as was the case in The Walking Dead, the story can be broken down into smaller episodes.

Figure 7: Rouse, R., Abernathy, T., (2014). Death to the Three Act Structure! Toward a Unique Structure for Game Narratives. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m6Hjfu0-oZY

Likewise, Kaufman(2019) proposes to look at sitcoms to structure free-to-play narratives, since both mediums don't know how many seasons will be done from the start – both sitcoms and F2P are aimed at an evergreen model. According to the speaker, this structure suits the mobile environment better. In sitcoms, characters with unresolvable dilemmas result in infinite scalability. Sitcoms present cliffhangers instead of one large story arc, and character-based scenes.

Figure 8: Kaufman, R., (2019). Narrative Nuances on Free-to-Play Mobile Games. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILFzKNLAwVQ

Incorporating mechanics and narrative

Throughout the last decade, we somehow established the notion of gameplay and story as opposed and even contradictory things.

As technology evolves we can notice a shift towards a more integrated approach. The old paradigm is holding us back, as Clint Hocking expresses to The Guardian(2014).

Chris Remo states in his 2019 GDC talk how important it is to "focus on the elements of the game that are going to speak to your priorities. Everything else is extraneous at best, and potentially works against your narrative goals".

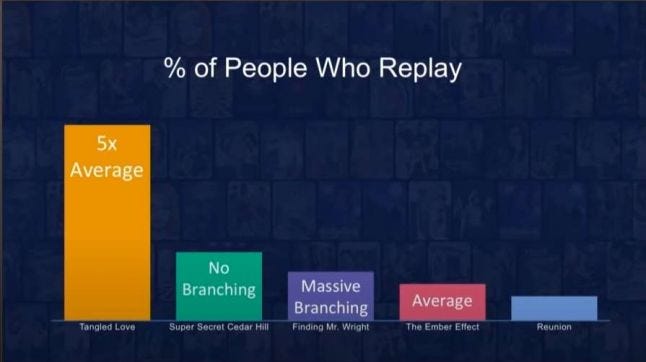

According to Cassie Phillips'(2016) metrics on multiple-choice romance games, the relationship to the characters is much more important for replayability than branching dialogue or choices that are meaningful to the plot itself.

The speaker estimates the industry standard to be about one choice every 20 or 30 minutes, and states that more choices don't affect retention significantly. Rather, it is about the emotional magnitude of each choice.

Figure 9: Phillips, C., (2016). All Choice No Consequence: Efficiently Branching Narrative. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEa9aSDHawA

Horneman(2015) explains how fiction and mechanics can inspire each other, giving the example of Deus Ex's black market system.

The equipment system in Deus Ex started as a purely mechanical feature, posterior to that, a narrative tone was added through the concept of the black market.

Figure 10: Horneman, J., (2015). The Design in Narrative Design. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8VIlfTtypg&t=478s

Another example of such narrative integration of a mechanical skill system can be seen throughout the Far Cry series. For example, Far Cry 3 borrows the Samoan tradition of tatau as a rite of passage. As the protagonist progresses and obtains more skills, those are represented by the progression of the tatau on his arm. Other instances of the series have opted for simpler skill systems embedded in their respective settings, such as Far Cry 5 using the more conventional first-person shooter concept of perks.

Figure 11: Negron, S., (2021). Far Cry 3: Jason's Tattoo & the Tatau Skill Tree, Explained. CBR. https://www.cbr.com/far-cry-3-tattoo-explained/

Sometimes we can even embed narrative elements into minor features or unavoidable elements such as loading times. In GoodGame Empire, for example, the initial loading screen features a made-up progress bar with random texts regarding plot elements instead of a functional progress bar, such as "sharpening the swords" or "kidnapping princesses", making reference to a questline.

Figure 12: GoodGame Empire. GoodGame Studios. https://empire.goodgamestudios.com/

Sometimes, however, a non-diegetic approach can be a better solution in terms of player feedback, as Horneman(2015) illustrates in his comparison between The Getaway and GTA V.

Thanks to the convention of having on-screen non-diegetic cues, suspension of disbelief can happen despite a lower fidelity.

Figure 13: Horneman, J., (2015). The Design in Narrative Design. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8VIlfTtypg&t=478s

On a similar note, Remo(2019) explains how the decision-making system in Firewatch was iterated, from initially using button input to later taking advantage of the existing mechanics.

In his example, he talks about a choice of picking up just enough food for oneself or ignoring the request and picking up more. Initially, the interaction held place by pressing one of two buttons, however, this mechanic was redundant since the game already had the mechanics for picking up objects, and by using that game mechanic it could become more immersive.

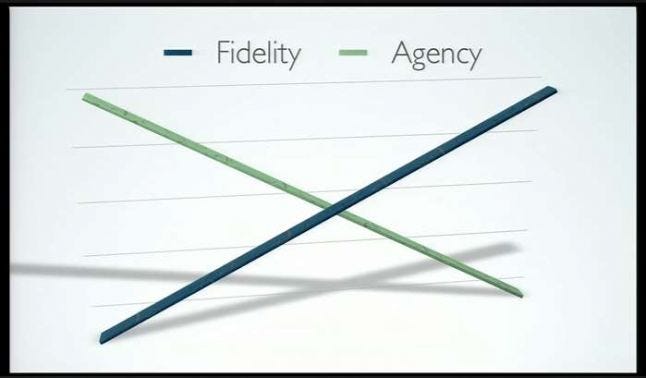

Hudson(2011) emphasizes this use of resources as well, drawing an inverse relation between fidelity and agency due to the cost of development.

Figure 14: Hudson, K., (2011). Player-Driven Stories: How Do We Get There?. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qie4My7zOgI&t=483s

As an example of how agency rather than fidelity can convey strong emotion, Hudson mentions the experimental game Passage.

Hudson's notion of fidelity against agency stands in parallel to Briscoe's(2013) GDC talk on Dear Esther, where the speaker emphasizes immersion as opposed to realism. To create the environment art, he drew inspiration from impressionist painting, discussing, in particular, the light and atmosphere, constrained color palette, and evoking emotion over reality. "it's not the fidelity of the content that matters, but the emotion and experience". He describes how he conveyed the story in small details and used subtle symbolism to represent the protagonist's journey, such as a barely noticeable heart shape and blue tones on entering the cave, which represents the protagonist's psyche, and a more noticeable eye shape on exiting it.

_The_Art_of_Dear_Esther_%E2%80%93_Building_an_Environment_to_tell_a_Story_-_YouTube.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Figure 15: Briscoe, R., (2013). The Art of Dear Esther - Building an Environment to tell a Story. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a2oREGSkFgM

Story and mechanics should not depend on one another. As Mehrafrooz puts it, "Building a game around a story tends to trap you in a variety of ways". Instead, all aspects should work in cooperation to form the final experience.

Application

Before any story comes to life it first has to be lined out on paper. Jamie Antonisse(2014) defines a narrative game prototype as "a playable, flexible outline of the premise, rules, events, and choices, built to answer the following questions: what is the "hero's journey" for the player? Do these pieces fit together into a compelling experience? Does it all make sense?"

According to Antonisse, a paper prototype should be made with a short deadline (3 days, or 1% of the planned development time), with few people, based on simple rules, including reference points, within a personal storytelling experience level, and focus on the central question of game narrative.

The first step is then an initial write-up, synonymous with writing initial notes for a book. This should include the premise, the player's role, goals (what motivates the player), conflict (what obstacles are in the way of those goals), actions, resources (simple to understand, elegant, giving opportunity, information, and challenge), and events.

Antonisse goes on to provide examples of his principles for the build-out.

The speaker recommends always showing the player their goal. In Journey, for example, it is the mountain with the light. There is no need to be told to go there, due to the strong visual cue.

Characters can be used as goals, resources, and conflict. In classic JRPGs, actions are personified as characters, as Antonisse states, and Donkey Kong is holding the goal but also throwing obstacles.

Finally, story events grow around the action. Keeping all that in mind, story points can be cut out that don't "reinforce or showcase goals, call the player to action, give the player feedback on their choices, or provide a break or reward after a heavy action."

The second step to a paper prototype is drafting out the rules. Actions should be simplified, as at this point we are not testing mechanics. Dice are a method to emulate a challenge since they stripe down player actions to a probability outcome, or a dartboard can serve for sequences in shooter games where mechanical aim is important for the story. At this point, "you may be simplifying action, but you want to keep the element of choice strong in the prototype. Identify your most important choice points and figure out what's behind either door."

The final step is to set up a game space that's going to abstractly represent the world for the player. This "board" should "have weight, be flexible and sticky, and have some simplicity and focus on it."

Once this system is built and makes sense to you, you want to build out your presentation. This is where you want to figure out how to communicate those rules and systems to the player in order to finalize and iterate on the prototype.

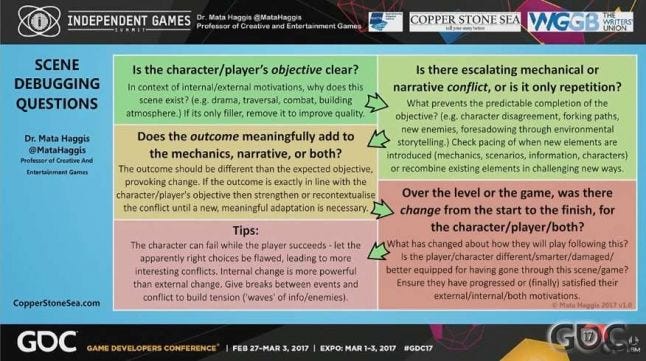

Similar to technically executed content, a story can be debugged as well to find issues, as Mata Haggis(2017) mentions. Those steps should ideally be followed periodically after any addition to avoid future time-consuming complications, but especially during the initial period.

Figure 16: Haggis, M., (2017).Storytelling Tools to Boost Your Indie Game's Narrative and Gameplay. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8fXE-E1hjKk

Once the vision is defined, outlines and tentpoles are clear, and a playable prototype is greenlighted, it is finally time to build out the story in its entirety, little by little. This is where the story bible (usually a Confluence space or, on smaller projects, a Trello board) comes into play, as Mehrafrooz explains, "it is important to "put everything together in a way that’s easily searchable so that any time someone on the team works on it, it’s all clear and coherent."

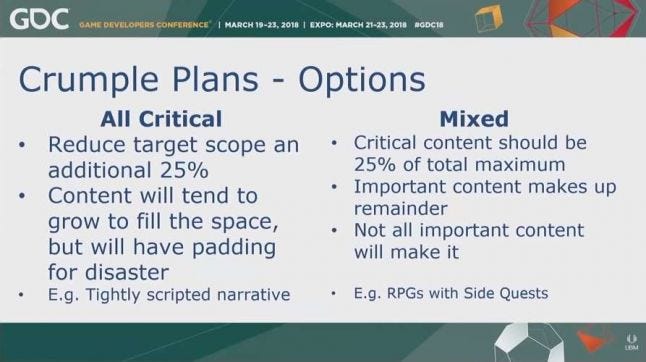

At any time, it is important to keep scope and scale in mind, and only iterate upwards on the MVP. In that regard, Laidlaw(2020) introduces us to the concept of "crumple planning", in other words, prioritization to prepare for the worst-case scenario. He proposes to classify tasks into critical or important, and, in the worst case, to be prepared to cut out over a quarter of the content.

Figure 17: Laidlaw, M., (2020). Empires to Ages: Storytelling Lessons Learned in 14 Years at BioWare. Game Developers Conference.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gsh-aYdFWws&t=120s

Further resources and recommendations

Even in seven parts, there is still a limit of information to fit into an article. The following section comprises a list of all the resources recommended by the referenced sources that were not explained thoroughly here, and some more.

Ayeesha Khan's(2019) recommendations:

tecfalabs, narrative theories

David Kuelz, narrative design tips I wish I'd known

tomkail.tumblr, irreducible complexity

Youtube, Extra Credits

Five act model

Hero's journey

Katie Chironis, getting a job in game or narrative design

ifdb.tads.org

emshort.blog, game writing, writing IF, narrative

voiceoverstudiofinder.com

gameindustry.biz, game voice casting

thevoiceovernetwork.com

Into the Woods, John Yorke

The Anatomy of Story, John Truby

The Game Narrative Toolbox, Heusser & Finley

Callum Langstroth's(2021) recommendations:

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee

Screenplay: Foundations Of Screenwriting by Syd Field

Into The Woods: How Stories Work and Why We Tell Them by John Yorke

Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction by Jeff VanderMeer

The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human, and How To Tell Them Better by Will Storr

Forest Paths Method for Narrative Design(Alexander Swords, 2020) and his GDC and GCAP talks

Christopher Alexander's A pattern language(1977), The timeless way of building(1979), and The nature of order(1981)

Patterns in Choice Games, by Sam Kabo Ashwell

Any artbooks as referrence for worldbuilding

The Writer's Journey, by Christopher Vogler

GDC talks that didn't fit in here entirely:

Warren Spector, 2013, Narrative in Games - Role, Forms, Problems, and Potential

Kent Hudson, 2011, Player-Driven Stories: How Do We Get There?

CJ Kershner, 2016, The Lives of Others: How NPCs Can Increase Player Empathy

Richard Rouse III, 2016, Dynamic Stories for Dynamic Games: Six Ways to Give Each Player a Unique Narrative

Winifred Phillips, 2020, From Assassin's Creed to The Dark Eye: The Importance of Themes

Anna Kipnis, 2015, Dialogue Systems in Double Fine Games

Miriam Bellard, 2019, Environment Design as Spatial Cinematography: Theory and Practice

Matt Brown, 2018, Emergent Storytelling Techniques in The Sims

Analysing narratives. play a lot and think about how the story is told, look especially for games out of your expertise and for those which are not necessarily story-centric, like casual mobile games.

Case studies used here can be found on Fallout 3 in Tynan Sylvester's(2013) book, or Wei et. al. On time and space in Assassins Creed.

Finding inspiration by looking at narrative in entirely different mediums, such as non-fiction(news, marketing, or simply everyday occurences and encounter) or music. A good example of a lyrical narrative analysis is given by Polyphonics on Aesop Rock's None Shall Pass on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4piBfjSKAL4

"The intention to live as long as possible isn’t one of the mind’s best intentions,

because quantity isn’t the same as quality."

- Deepak Chopra

Epilogue

Don't think about easter eggs and sublime clues until the very end, unless a core mechanic is about finding them. As Kennedy(2016) summarizes, content, if not noticed by the player, didn't happen. The more the player notices it, the more it happens. And the more happens, the less will the player be able to notice what happens. Attention is a finite resource – prioritize quality over quantity.

“If you do follow your bliss you put yourself on

a kind of track that has been there all the while,

waiting for you, and the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living.

Follow your bliss and don't be afraid,

and doors will open where you didn't know they were going to be.”

- Joseph Campbell

As Van de Meer(2019) concludes, "What you need to remember is that these explanations of the narrative structures are not hard and fast rules." Despite all the tech talk, research, and organization in the world, storytelling remains a form of art. And just like any art form, the quintessential aspect is to stay true to one own, individual, unique self. Stories are stories, are not structure! (Rouse, Abernathy, 2011)

As writers and designers, we also have a certain responsibility as our work can indeed represent a driver for social change, both positive and negative. According to Murrar and Brauer(2019), "While educational institutions and workplaces are increasingly taking steps to promote openness to diversity in public spaces, the real power to change people’s hearts and minds may lie in the television programs, books, and other media we consume on a daily basis."

This notion of responsibility is furthermore emphasized by Nagler(2015), who states that it is important to add breaking points "to let the player reflect, get out of character again. We do not want to condone a character's actions, especially if they are morally difficult. It is something only games can do, and I think we should try to do it as good as we can."

"Confidence comes from doing the same thing over and over again,

but it takes courage to change that."

Mick Gordon, GDC 2017

Thanks to the people who commented, both on social media and on the articles themselves, your feedback is highly valued!

Anyone can free to reach out on LinkedIn to discuss or simply network.

Previous parts:

Part 1: Prologue

Part 2: Setting and Tools

Part 3: Freedom of Choice

Part 4: Structure and Devices

Part 5: Character Design

Part 6: Time and Space

References

Laidlaw, M., (2018). Empires to Ages: Storytelling Lessons Learned in 14 Years at BioWare. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gsh-aYdFWws

Mehrafrooz, B., (year unknown). The Ultimate Guide to Game Narrative Design. Pixune. https://pixune.com/game-narrative-developing-a-story-that-works/

Weekes, P., Epler, J., (2016). Dragon Age Inquisition: Trespasser – Building to an Emotional Theme. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ao4b4aN7RgE

Dark Horse Books (2011). The Art of Alice: Madness Returns

Rouse, R., Abernathy, T., (2014). Death to the Three Act Structure! Toward a Unique Structure for Game Narratives. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m6Hjfu0-oZY

Kaufman, R., (2019). Narrative Nuances on Free-to-Play Mobile Games. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILFzKNLAwVQ

Remo, C., (2019). Interactive Story Without Challenge Mechanics: The Design of Firewatch. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVFyRV43Ei8

Phillips, C., (2016). All Choice No Consequence: Efficiently Branching Narrative. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEa9aSDHawA

Horneman, J., (2015). The Design in Narrative Design. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8VIlfTtypg&t=478s

Briscoe, R., (2013). The Art of Dear Esther – Building an Environment to tell a Story. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a2oREGSkFgM

Antonisse, J., (2014). Building a Paper Prototype For Your Narrative Design. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=taxcb_5lEI8

Laidlaw, M., (2020). Empires to Ages: Storytelling Lessons Learned in 14 Years at BioWare. Game Developers Conference.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gsh-aYdFWws&t=120s

Haggis, M., (2017).Storytelling Tools to Boost Your Indie Game's Narrative and Gameplay. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8fXE-E1hjKk

Kennedy, A. (2016). Choice, Consequence, and Complicity. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-FfITxaXeqM

Van de Meer, A., (2019). Structures of choice in narratives in gamification and games. UX Collective. https://uxdesign.cc/structures-of-choice-in-narratives-in-gamification-and-games-16da920a0b9a

Murrar, S., & Brauer, M. (2019). Overcoming Resistance to Change: Using Narratives to Create More Positive Intergroup Attitudes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(2), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721418818552

Howitt, G., (2014). Writing video games: can narrative be as important as gameplay?. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/australia-culture-blog/2014/feb/21/writing-video-games-can-narrative-be-as-important-as-gameplay

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)