Storytelling in Games and Interactive Media. Chapter 6: Time and Space

When it comes to interaction, the notion of spatial change over time through player action can become a complicated issue in building your story.

Chapter 6: Time and Space in an interactive medium

Of course, in the end, the personal story is always experienced linearly – even if it is built out of non-linear components. (Claussen, 2017)

Herman(2002) coins the term storyworld, referring to the digital world created through the player's mental construction bridging the gaps left in-between textual, visual, auditory, and haptic cues. (Wei et al, 2010)

Games are a temporal narrative medium (Wei et al, 2010) in that players drive the plot forward through gameplay over time(Dinehart, 2019). Citing Arsenault and Perron, Wei et al. argue that time and space can be seen as separate, yet connected aspects of experience, "since gameplay occurs through a series of interactions that take place in patterns of reflexive and cyclic progression. In our construction of a story world, time and space are two aspects that complement and reference each other."

There is extensive research evidence that mature comprehenders engage in the necessary cognitive processes to encode causal connections in memory. Adult comprehenders remember events that have more causal connections and rate them as more important to the narrative. (Lynch et al., 2008)

The cognitive process of narrative comprehension is analogous to player experience during gameplay. As Jenkins observes, players form their “mental maps of the narrative action and the story space” and act upon those mental maps “to test them against the game world itself”. Nitsche views narrative as “a form of understanding of the events a player causes, triggers, and encounters inside a video game space”. (Wei et al., 2010)

Space and time connected

Aarseth(2001) claims spatiality to be the defining element in digital games. "Games are essentially concerned with spatial representation and negotiation; therefore the classification of a computer game can be based on how it represents or, perhaps, implements space".

Wei et. Al(2010) follow up on Aarseth's claim, stating that various classifications of game space exist, including Wolf's 11 spatial structures based on film theory's on-off screen dichotomy, or Boron's historical approach defining his 15 types of game space.

Jenkins(2002) suggests four ways in which the structuring of game space can facilitate narrative experience. (Wei et al., 2010)

According to Jenkins, “spatial stories can evoke pre-existing narrative associations; they can provide a staging ground where narrative events are enacted; they may embed narrative information within their mise-en-scene; or they provide resources for emergent narratives”

Nitsche(2007) argues that mapping game time onto game space can only be done with spatial reference thanks to the continuity of space. Time in games can be stopped, reversed, or altered, which can cause problems when trying to denote a specific time point. Spatial reference is, therefore, more stable. (Wei et al., 2010)

Using an architectural approach, Nitsche categorizes spatial structures into tracks/rails, labyrinths/mazes, and arenas. Similar to Jenkins, he observes that evocative narrative elements can be organized according to spatial structure – the player's experience is therefore driven by space. (Wei et al., 2010)

Bakhtin(1937) challenged the opposition of time and space proposing the term chronotope, referring to the connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships. Juul(2004) and Zagal and Matea(2008) build upon Bakhtin's notion to define their frameworks for space-time in games. (Wei et al., 2010)

Classification of narrative time

Most approaches depart from the distinction of two temporalities, storytime and discourse time.

Storytime is the basic sequence of events, the chronological order in which events happen. Discourse time, on the other hand, can be seen as "time as told", and thus be understood differently according to the context. In digital games, storytime remains similar, while discourse time becomes more complex. It should refer to both "reading time" and "acting time". Thus, we refer to operational time to refer to the running process of a game driven by player's actions and the game's autonomous mechanisms. (Wei et al., 2010)

The relationships between those two schemes can produce many interesting narrative effects. These relationships are classified by Genette as order, duration, and frequency. (Wei et al., 2010)

Herman uses "fuzzy temporality" to describe temporal relations that involve intentional inexactitude. He defines "polychrony" to cover all types of narration with fuzzy temporality. This notion complements Genette's classification as a fourth category of temporal relations. (Wei et al., 2010)

Juul proposes the classification into playtime and fictional time, and uses the term projection to describe the link between playtime and fictional time. (Wei et al., 2010)

Juul argues that variable speed can influence the mapping of playtime and event time. Many action games, such as Quake III offer a direct temporal mapping, while in a game such as SimCity the construction of buildings takes only minutes or seconds. (Nitsche, 2007)

Following the mechanics given by building simulators such as SimCity, the realm of Free-to-Play opens up for a common use of projection in matters of monetization, as illustrated here by GoodGame Empire:

Figure 1: GoodGame Empire. GoodGame Studios. https://empire.goodgamestudios.com/

Hitchens extends on Nitsche to present a new model for game time, dividing it into playtime, game world time, engine time, and game progress time. Tychsen et al. Build upon Juul's model in the context of multiplayer role-playing games, creating their seven-layer model. Zagal and Matea propose four temporal frames for games: real-world time, gameworld time, coordination time, and fictive time. (Wei et al., 2010)

Order against linearity

Herman(2002) rejects narrative time to be determinable or indeterminable. Citing Margolin's notes, he states that a given set of events can be ordered in four ways: Full ordering(possible to assign an order), random ordering(all orderings are equally possible), alternative or multiple ordering(probability of one ordering can be higher than the other), and partial ordering(events can be “uniquely sequenced relative to all others, some only relative to some others, and some relative to none” ). (Wei et al., 2010)

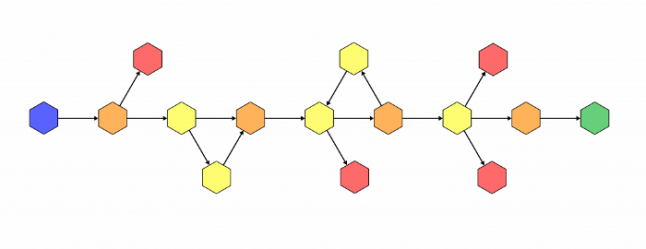

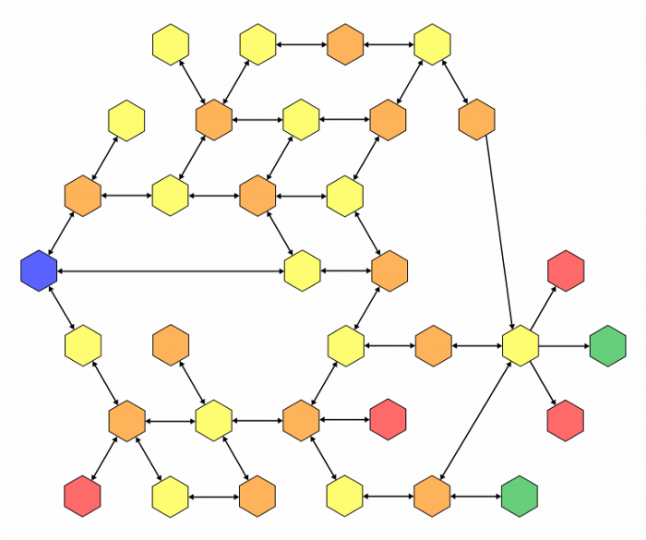

In a polychronic narrative, events can be inexactly ordered, inexactly coded, or both. A common method of creating nonlinear story is to allow varied orderings. To ensure that the game still follows an overarching story, foldback structure is very popular, used to balance agency at a local level with narrative at a global level. Foldback structure divides the game into several chapters and accommodates multiple plot variations. While players can go through a different set of events or a different order, inevitable events or gates occur between parts. (Wei et al., 2010)

Figure 2: Van de Meer, A., (2019). Structures of choice in narratives in gamification and games. UX Collective. https://uxdesign.cc/structures-of-choice-in-narratives-in-gamification-and-games-16da920a0b9a

Order concerns the relation between the order of events (discourse time) and their chronological sequence as constructed by the viewer (storytime). In games, order is the relation between the ordering in operation and the ordering in the story. When these two orderings are consistent, it results in a linear story. As Adams points out, linear stories can have more narrative power and emotional impact, at the cost of a corresponding loss in player agency. (Wei et al., 2010)

Managing order through logic

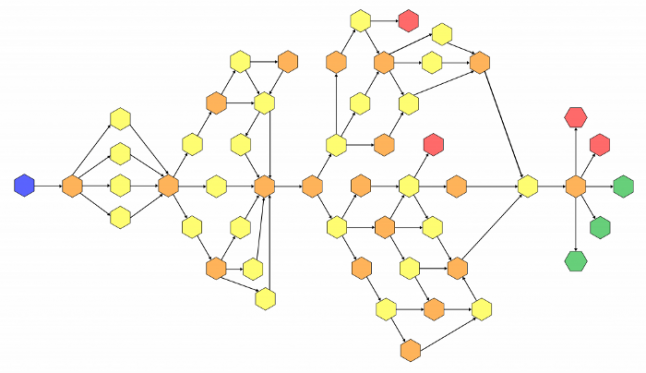

Addressing the issue of order, Ingold(2018) talks about his design process as seeing all content as "atomic". He defines narrative atoms as any block of player action, including dialog. Atoms are interdependent, and their relationship is guarded by preconditions. Those preconditions must be satisfied for the atom to be allowed to surface.

Ingold furthermore classifies preconditions into three states: world state (where is the player, what is visible, what is open/closed, what does the player have, who else is there,...), technically managed through mechanics such as trigger volumes, raycast, or state machines. Knowledge states (what does the player know, what do they need to know, what leads are they following), and recent past (what has just happened, what did the player recently do, what has the player talked about,...).

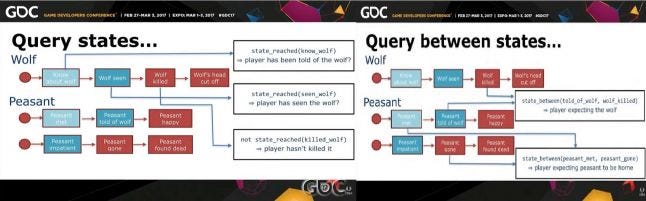

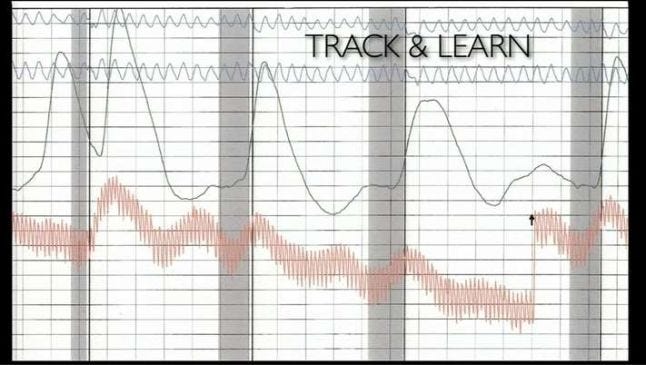

This form of technical execution allows the designer to add atoms responsively. Thanks to the use of preconditions, non-linear flow happens naturally. however, the writing process is tedious, repetitive, and error-prone, since, on any piece of dialog, the designer needs to list every single way it would be inappropriate to say, on every single option in the game. To cope with that issue, authoring patterns are used. To solve this issue, the speaker further divides atoms into hierarchical scopes, as he puts it, "buckets of context".

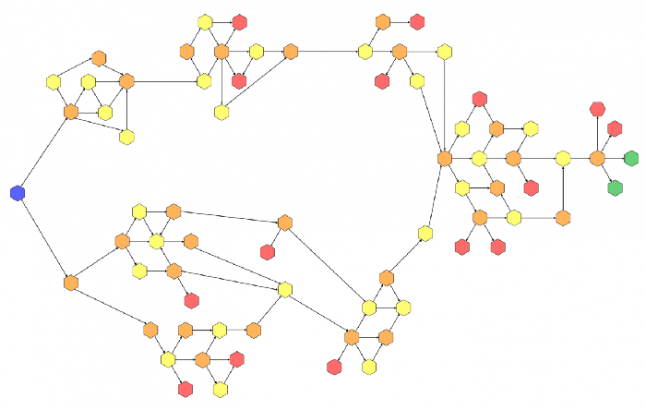

Figure 3: Ingold, J., (2018). Heaven's Vault: Creating a Dynamic Detective Story. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o02uJ-ktCuk&t=590s

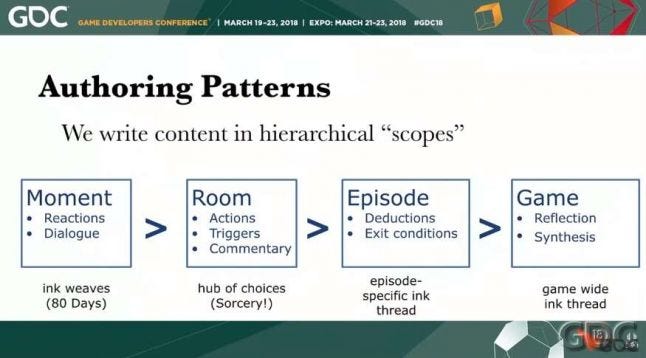

Elan Ruskin(2012) refers to Herman's(2002) concept of "fuzzy logic" as used in Left4Dead for character dialog. According to the speaker, it is easy to think of dialog in terms of conditions. On-event, a set of conditions and priorities is called to decide which line the character will say. For example, a character's dialogue line after being bitten could overwrite the default line when located in a circus environment, consecutively the circus-related line could be overwritten if bitten by a clown unless the clown-related line had already been triggered within a certain timeframe.

Sylvester(2013) lists a variety of mechanical devices being used to enforce story ordering. Levels are a classic device. Similarly, quests offer a softer ordering device. Sylvester defines a quest as "a self-contained mini-story embedded in a larger, unordered world."

Within the quest sequence, the order of events is fixed. But the quest could be started at any time, suspended, or eventually abandoned.

Sometimes users are given control over the order of the story, especially in the realm of open-world games. In the Noclip documentary on The Witcher 3 quest design, Lead Quest Designer Mateusz Tomaszkiewicz explains how they solved the issue of anticipating player-acted order on the example of the "Lord of Undvik" quest, where the player could find his target before actually talking to the quest-giver. Through Herman's fuzzy logic, this narrative problem was solved the same way Left4Dead handles its dialogue, by changing the lines depending on whether state the player-perceived narration was in at the time of obtaining the quest.

Jon Ingold(2017) addresses the issue expressed by Wei with his concept of encounters. While quests would follow a mostly linear logic, with the only controlling device being the availability of quest giver and resources, completion requisites, and triggers, encounters are built flexibly depending on the world state. In Sorcery, flowcharts were used to line out those encounters to follow the current world state:

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Figure 3,4: Ingold, J., (2017). Narrative Sorcery: Coherent Storytelling in an Open World. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZft_U4Fc-U

With longer plotlines, this can get utterly complex, which in turn was solved through state machines. They are "state trees that depict the causality in your game".

Figure 5,6: Ingold, J., (2017). Narrative Sorcery: Coherent Storytelling in an Open World. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZft_U4Fc-U

The third ordering device is the blockage. Blockages can be things like locked doors, to which a key has to be retrieved, guards that won't let the protagonist pass unless they receive a favor, or security cameras that need to be disabled. (Sylvester, 2013)

Sylvester(2013) mentions skill gating as a softer ordering device. Other common gating techniques are level gating or time gating.

Skill gating is categorized as a soft ordering device since players can access all the content from the first moment. However, some of the content requires to exercise skill before being accessible. Players end up experiencing the content in rough order as they progress along the skill range, even though the content is technically available from the start. (Wei et al., 2010)

Level gating on the other hand does not make the content available from the start. It still allows for a customized player experience, while enforcing order based on the avatar's level rather than player skill.

Time gating makes use of the dissonance between playtime and event time. With time gating, content is released based not on progress, but on real-world time. This serves a variety of purposes depending on the situation. For example, a game such as Life is Strange could be released episodically, allowing players to experience the content while the next episode was still being developed. It can also serve to limit progress in repeatable quests through cooldown. For example in World of Warcraft, some quests can be repeated to gain reputation. While daily or weekly replayability also serves retention, the ability to repeat those quests without cooldown would allow the player to level up beyond the according range, skipping relevant parts of the content and damaging the difficulty balancing by not receiving other rewards.

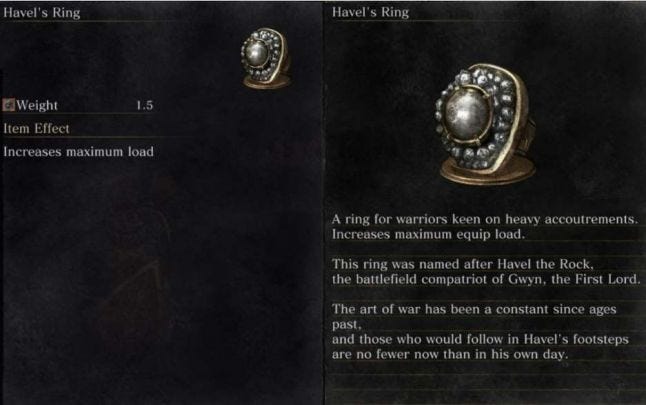

Ordering is not limited to high-level narrative structure but also concerns the many pieces of information that are released on a micro-level throughout the experience, such as elements of the world narrative, or flavor texts like in item descriptions. (Mehrafrooz, n.d.)

Figure 7: Mehrafrooz, B., (year unknown). [screenshot from Dark Souls III, FromSoftware Inc.]. The Ultimate Guide to Game Narrative Design. Pixune Studios. https://pixune.com/game-narrative-developing-a-story-that-works/

Narrative ordering is furthermore a method for controlling difficulty. The next screenshot shows a tooltip from a "shadow attack" in GoodGame Empire. While the story of shadow mercenaries is unrelated to the overall game's story, the event introduces a new mechanic to the gameplay, which first has to be learned. Here, level gating is used to make the event unavailable to newer players, avoiding cognitive overload.

Figure 7: GoodGame Empire. GoodGame Studios. https://empire.goodgamestudios.com/

Branching and the butterfly effect

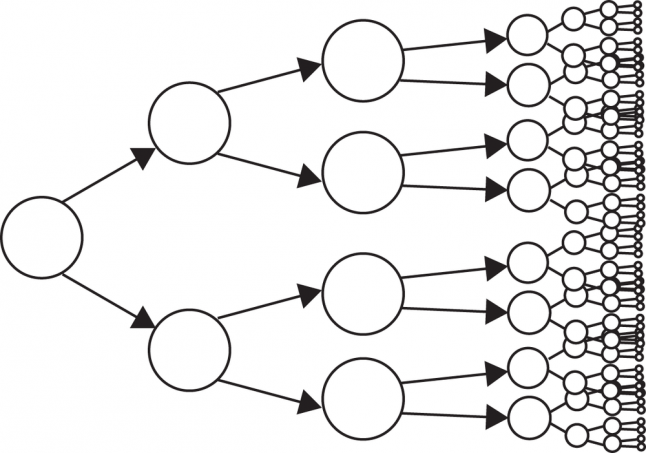

Another common nonlinear technique is branching plotlines (Wei et al., 2010). The issue with branching plotlines, according to Sylvester(2013) is that the number of timelines rapidly explodes.

Figure 8: Sylvester, T. (2013). Designing Games. O'Reilly. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-games/9781449338015/ch04.html

The problem presented by Sylvester is best illustrated by the notion of magnification in chaos theory. In Love, Death, and Robots, episode 15 "alternate histories", the spectator is put in a first-person role and is advertised the fictional app "multiversity", which applies branching plotlines to real-world history. At the beginning of the 6-minute-long episode, we are presented with 6 alternate timelines included in the "demo". Starting from a clear causality, the episode proceeds to further illustrate chaos theory(E.Lorenz, 1963), commonly metaphorized as the butterfly effect.

In classical mechanics, the behavior of a dynamical system can be described as motion on an attractor. The mathematics of classical mechanics recognize three types of attractors (regions or shapes to which points are pulled): single point (steady states), closed loops (periodic cycles), and tori (combination of cycles). A strange attractor displays sensitive dependence on initial conditions. On strange attractors the dynamics are chaotic. It was later recognized that strange attractors have detailed structures on all scales of magnification. (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2021)

We can see how Alternate Histories shows how (non-)linear the effects of seemingly similar events can be due to the magnification effect. Indeed this episode goes so far to display different degrees of (non)-linearity, based on May's(1976) logistic map. As narrative designers, we can make use of chaos theory to define to which extent a given event should affect our story's timeline and find a common ground between credibility and available resources.

This notion should be considered when writing our flowcharts in the case of branching plotlines. Any player decision, as small as it can be, can have "unpredictable" effects on the outcome of the story!

Through careful planning and reasoning in the early stages, we can create sense while limiting our narrative's scope to a conceivable complexity.

Sylvester(2013) argues that the only situation in which branching plotlines are a feasible structure is if almost all content is generated emergently. If events are predefined to any significant degree, it is necessary to reduce the number of branches.

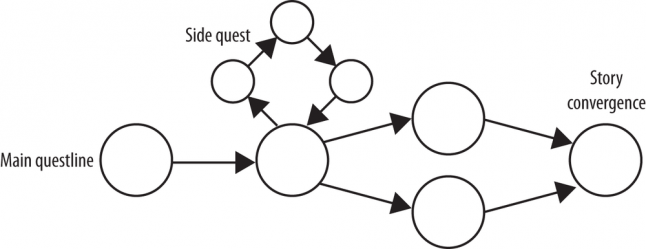

Sylvester proposes to retain some of the choices by using devices such as side quests and story convergence(foldback).

Figure 9: Sylvester, T., (2013). Designing Games. O'Reilly. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-games/9781449338015/ch04.html

A popular example can be seen in Life is Strange: Here, options have individual probabilities on the outcome, however, those probabilities are themselves altered by previous player decisions. (Nekumanesh, 2016)

Following an overall foldback structure, the occurrence of the storm(climax) is unavoidable, as it is the effect of magnification of the initial state(Max saving Chloe). Not only does this limit the project's scope to a reasonable level, but it also drives the spectator towards the emotional highlight at the end, which although reducing replayability, is clearly the intention as the final scene pretty much conveys the core sentiment of the narrative.

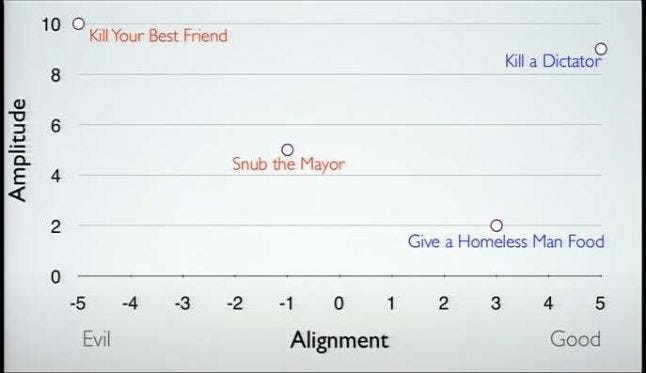

Hudson(2011) proposes an amplitude-alignment scale to bring order into this chaos. According to Hudson, if we understand these smaller events, we can estimate a realistic effect.

Hudson, K., (2016). Player-Driven Stories: How Do We Get There?. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qie4My7zOgI&t=483s

By feeding information to a database and having the game understand causal relationships, the game can organically react to the player's actions over time. According to Hudson, this is often done especially well in strategy games. Doing so strongly affects the emergent outcomes, rather than being considered as branching storylines, since the game organically reacts to the player's actions instead of having a finite list of outcomes.

Figure 10: Hudson, K., (2016). Player-Driven Stories: How Do We Get There?. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qie4My7zOgI&t=483s

Temporal devices in interactive narrative

The term of speed refers to the relation between the duration of events and the duration of the discourse. In games, this would be the relation between the operation of an event and the duration of that happening in real-world time. Bal summarizes five canonical tempi that can be used as relative measurements, here ordered from fast to slow: ellipsis, summary, scene, stretch, and pause. (Wei et al., 2010)

In ellipsis, there is a skip of story events in operational time. Wei et al.(2010) give the example of Fable II, where the protagonist worked for ten years as a labourer. The game only selects three moments, from weeks 1, 38, and 137, to the present.

Ellipsis can be used as a dramaturgical device, as Chris Remo(2019) expresses in his conference talk addressing the issue of freedom of movement in Firewatch: "how would we maintain the kind of tension and pacing that's necessary for a paranoia involving story like ours in this situation; the narrative spine of true open-world games often suffers when the sense of momentum is undercut by the player having so much freedom that the illusion of time and urgency is broken".

In order to resolve the given conundrum, the speaker draws inspiration from the film Dallas Buyers Club, which hard-cuts through the narratively significant days, and therein underlines the sense of urgency. According to Remo, those decisions come with a lesser sense of exploration as a tradeoff, and can only be taken when having established clear priorities – in this case, storytelling over player freedom.

Summary refers to a duration wherein operational time is shorter than storytime. As the name suggests, it is used to show a major leap without the details happening in between. For example in Fable II, the protagonist grows up in a short cutscene showing the change of seasons accompanied by a voice-over. (Wei et al., 2010)

We increasingly see summary balanced to become a monetization and retention tool, as is the case with cooldowns, building or movement times, or to balance cost through the resource of time, such as World of Warcraft's crafting times depending on the value of the crafted item, or Age of Empire's building and recruitment times.

In games, there is not necessarily an absolute scene speed, as events need to be computed. Wei et al.(2010) compare the duration of fighting action of two games in their thesis: Fable II, where the duration roughly matches real-time, and The Legend of Zelda: Phantom Hourglass, which can be sped up through player input. They conclude that "as long as the sequence takes place within a reasonable range of duration considering the scale of the game, we can consider its speed as scene".

Kelley(2007) suggests that syncing with real-world time, as in cases such as Animal Crossing, “intentionally draws on the passage of time to create both emotional resonance and economic value in the gameworld” (Wei et al., 2010)

Stretch is the opposite of summary, when an event takes longer to happen in the operational time than in storytime. An example is bullet time, popularized by Matrix and adapted in games by Max Payne. (Wei et al., 2010)

Lastly, a pause occurs when a story event is paused and the operation is taking care of something else. This is the case of the use of cutscenes to show the newly entered terrain through a camera pan, as is done in many action-adventure games like Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, Assassin's Creed, or Tomb Raider. Another type of pause is the user-commanded pause. This type of pause can be considered a UX element, unrelated to the experience or analysis of the narrative. (Wei et al., 2010)

Frequency refers to the relation between the number of times an event happens in the story and is presented in the operation. When an event took place several times in the story but is presented only once, it is referred to as iteration, while when an event takes place only once in the story but multiple times in operation, repetition happens. Other than in verbal narration, iteration is not common in visual mediums. (Wei et al., 2010)

Repetition is more common, although mostly employed as a mechanic rather than a narrative device. The most common repetition is the possibility to retry a failed challenge. In this type of repetition, events in operation may vary, but story events remain the same. It helps the player master mechanical skills but is less relevant to the narrative experience. (Wei et al., 2010)

Another type of repetition is player's choice. Players may revisit certain sections and repeat tasks, and some games offer variations for the repeated section. This type of repetition adds to the player's experience in both gameplay and narrative (Wei et al., 2010). A popular example is unlockable difficulty modes as seen in Borderlands or Diablo III, for example.

The third type of repetition results from the player's ability to reverse time, as is the example of the Dagger of Time in Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time or Max's rewind ability in Life is Strange. (Wei et al., 2010)

Spatial devices in interactive narrative

We consider a game's narrative space as the space of the game's storyworld. Nitsche(2008) frames game space under structure, presentation, and functionality. Discussions under structure look at how textual qualities are reshaped by 3D game space. Presentation focuses on the roles of moving images and sound, and functionality addresses the player's interactive access to the game space. (Wei et al., 2010)

Zoran recognizes that the structure of space influences the reconstructed storyworld, and distinguishes three levels of spatial structuring: The topographical level (space as a static entity), the chronotopic level(space imposed with events and movements), and the textual level (space imposed with verbal signs). (Wei et al., 2010)

Zoran borrows Bakhtin's notion of chronotope to address the role of time in space. At the chronotopic level, space is structured by events and movements that happen over time. (Wei et al., 2010)

Textual structure investigates how textual patterns are imposed on the organization of space. Player actions influence the storyworld through events and movements, which in turn cause changes in the on-screen and off-screen spaces. According to Wei et. Al(2010), this calls for a modification of Zoran's two levels, defining an operational and a presentational view. In the operational view, the story unfolds over time through events, the storyworld is revealed through movements. Game operations impose movement and interactive patterns on the structure of space. In the presentational view, the dynamic presentation of the storyworld imposes its patterns on the structure of space.

Game space in the topographical view

The topographical level treats space as a static entity with fixed spatial reference, separated from temporal reference. Terms like layout, spatial organization, and spatial structure are related to the topography of game space. In this view, maps can be drawn based on ontological principles like treasure chests.

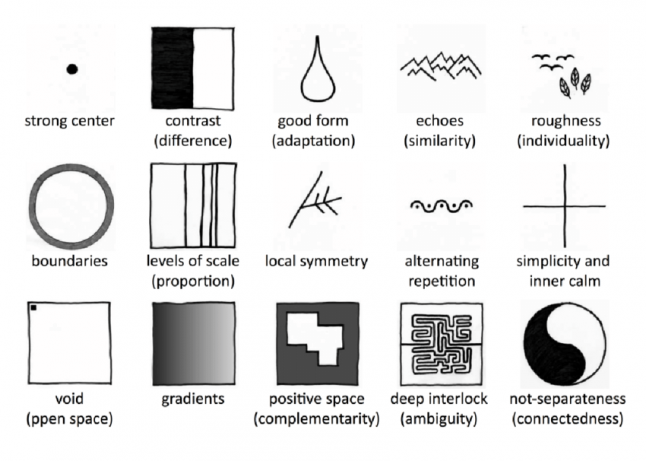

Jesse Schell(2018) talks about elements of the topographical level referring to Christopher Alexander's patterns(1977) and how this work inspires him in environmental storytelling.

In The Nature of Order (1981), Alexander defines 15 patterns that anything lasting has.

Briefly listed, Alexander's 15 principles are: levels of scale (elements intensify each other when they are in different size), strong centers (a whole contains focal centers within it), boundaries(the center is intensified when bounded), alternating repetition(elements are intensified when repeated with subtle variation), positive space(a living whole has only strong centers, where every part of space has the positive shape as a center), good shape(a living whole has a good shape and is made of smaller good shapes), local symmetries (a living whole contains various symmetrical segments that interlock and overlap with each other), deep interlock and ambiguity (a living whole has some forms that interlock centers with its surroundings), contrast (elements are intensified by the sharp distinction between the character of the element and its surrounding elements), gradients(qualities vary gradually), roughness (living wholes have some local irregularities), echoes (a living whole contains deep underlying similarities within it), the void (elements are intensified by the existance of an empty center), simplicity and inner calm (a living whole has certain slowness), and finally not-separateness (elements deeply connect and melt into their surroundings). (Takashi, Shingo, 2014)

Figure 11: Leitner, H., (2015). A Bird’s-Eye View on Pattern Research - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Diagrams-for-Alexanders-fifteen-properties-of-living-structures_fig7_305618476 [accessed 28 Feb, 2022]

Schell compares Alexander's pattern of "levels of size" to a game narrative in that "plot" is a "big" concept, "character" is medium, and "dialog" is a small component. All of those elements compliment each other and should be seen as interdependent and equally qualitative.

Schell argues that missing a "Strong Center" is what currently avoids choose-your-own-adventure novels to be successful.

He references "center" as the central notion on which the game is based.

Strong centers, according to the speaker, are created by "Boundaries", synonymous with thresholds in Campbell's Hero's Journey. He mentions the rules in Papers, Please as a form of boundaries that can be violated.

Schell refers to "Alternating Repetition" in the context of flow theory and tension waves, the continuous alternation of rest and tension.

"Positive Space" as opposed to negative space, according to Schell, can be seen in a narrative as dialogue as opposed to Silence. He references Oxenfree's possibility of interrupting dialog or remaining entirely quiet.

"Good Shape" refers to shapes that are appealing and functional on their own. On a narrative level, Schell refers to "shape" in temporal terms, as the "rhythm of interaction". He refers to The Walking Dead's popup message "<name> will remember that" as a powerful shape.

"Local Symmetries", as opposed to global symmetry, is a concept possibly known to riggers, and can be equally seen in nature, arts, and architecture, for example.

"deep interlock" is the interlocking of parts to create solidity. Schell references Terrence Lee, who differentiates between explicit (or scripted) and player story(world and emergent narrative or soft scripting). Interlock, according to Schell, comes into play as the notion of synergy between explicit and player story.

Schell refers to "Contrast" via comedy, then turns to Undertale to explain this contrast: "the serious parts make the funny parts more funny, and the funny parts make the serious parts more serious".

He references One Hour/One Life as an example of "Graded Variation", which in accordance to the speaker is not often used in games but can be really powerful.

"Roughness" summarizes all the little imperfections that make something feel original and real.

Schell references Cuphead to explain "Echoes", as the gameplay "echoes" the core of the story about "jumping into danger".

"The Void" refers to empty space. Schell explains this through the notion of increased importance when entering an empty space – it gives the sense that something important is about to happen.

Schell explains "inner calm" as that when everything else is removed, and only what is needed is left, a sense of calm is what remains.

He references the dots in packman for simplicity, as they serve multiple functions (points, progress, etc) at the same time without the need to add further complexity.

"Not-separateness" is how things are fundamentally connected. Schell references Brothers as an example, where two characters are controlled each with one hand.

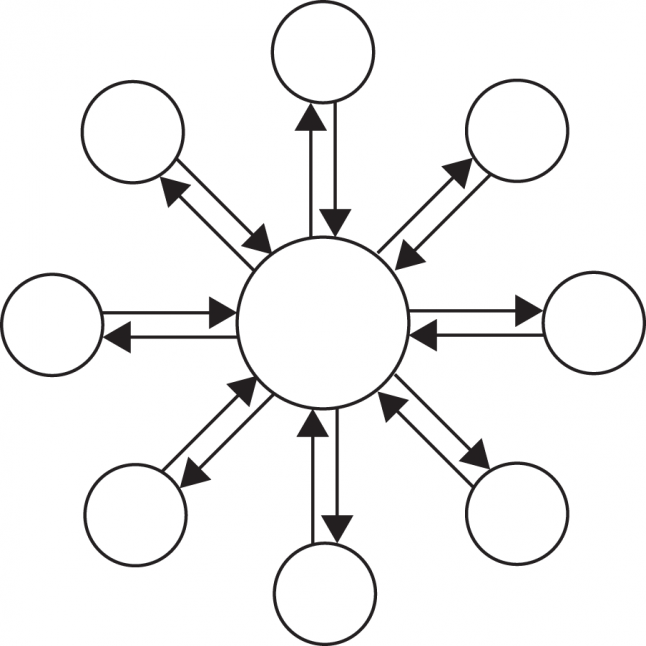

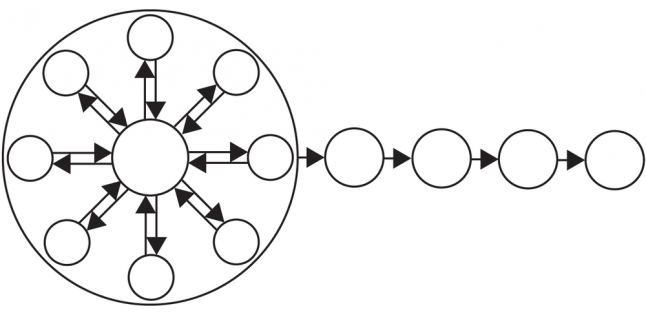

Adams considers a successful layout needs to be “appropriate for the storyline and to achieve the atmosphere and pacing required to keep players engaged in the game world” and gives a list of 7 common patterns of spatial layouts: open, closed, linear, parallel, ring, network, and hub-and-spoke. (Wei et al., 2010)

Following Alexander's principles, we can conclude that the term layout, as Adams uses it, refers to both the layout of individual spaces and the mapping of connections between those spaces.

An open layout gives the player the freedom to wander. When a player goes indoors or underground, the layout often switches to a network or combination layout. The settings mimic their corresponding real-world locations and have few spatial boundaries.

A linear layout is not bound to any specific shape but does ensure a fixed sequence. It stands similar to Nitsche's tracks and rails.

A parallel layout is a variation of the linear layout, that allows the player to switch from one track to another.

A ring layout makes the player's path return to the starting point, often used in racing games.

A network layout provides more ways of connecting spaces and grants more freedom of movement.

And finally, a hub-and-spoke layout starts the player from a hub in the center before heading out to another space (Wei et al., 2010).

An obvious example of hub-and-spoke can be seen in Among Us, where players are spawned at the center again at the beginning of each round. Another example is the hub in Mega Man. Each spoke is self-contained, independent from the others, and connected through the hub. (Sylvester, 2013)

Figure 12: Sylvester, T. (2013). Designing Games. O'Reilly. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-games/9781449338015/ch04.html

Adams reminds us that designers are not confined to one layout (Wei et al., 2010). It is often required to combine ordering devices to fit the needs of the game. For example, Mega Man 2 starts in a hub and spokes model, allowing the player to defeat levels in any order before being able to advance to the game's linear conclusion. (Sylvester, 2013).

Figure 13: Sylvester, T. (2013). Designing Games. O'Reilly. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-games/9781449338015/ch04.html

Spatial oppositions can be used to structure the story world and create the desired effect. Bal stresses that "oppositions are constructions; it is important not to forget that and "naturalize" them", and Zoran considers the map of a topographical structure as based on a series of oppositions. (Wei et al., 2010)

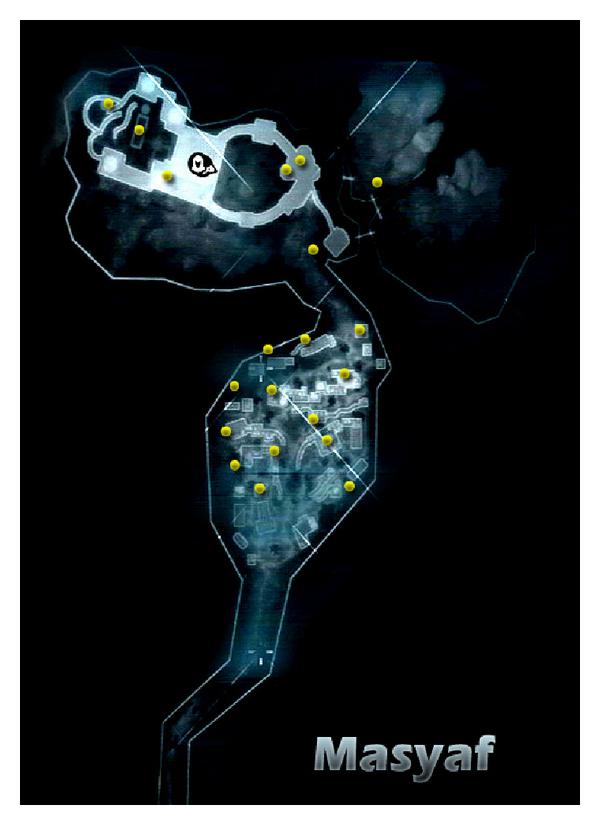

Spatial oppositions are typically physical (inside/outside, city/country,...) and can be endowed with meanings or experiences. For example, in the Assassins Creed series, the rooftop is an open and safe space while on ground-level, the player needs to be careful about the taken actions. This opposition allows for personalized pacing, and "illustrates how the design of narrativized space can affect ludic play". (Wei et al., 2010)

Apart from shaping the gameplay experience, spatial opposition can group narrative elements and simplify complex content. For example, in Masyaf in Assassins Creed, the upper part represents the mountain fortress and the lower part the village. These two places contrast in busyness and density, naturalizing a state of alert in the village part while, in contrast, the fortress serves as a home region. The convention created through spatial opposition helps players to easier adapt to the environment. This notion of opposition is reused throughout the series, although on varying scale. (Wei et al., 2010)

For example, in World of Warcraft, it is noticeable how sudden the textures change between locations. On one hand, this transition is likely due to engine limitations at the time but functions within the narrative function of providing a clear opposition between locations.

Figure 14: Huaxin Wei, Jim Bizzocchi, Tom Calvert, "Time and Space in Digital Game Storytelling", International Journal of Computer Games Technology, vol. 2010, Article ID 897217, 23 pages, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/8...

The transitory space or boundary between two locations often functions as a mediator(Wei et al.(2010), citing Bal(2009)). For example, in Masyaf, the passage between the mountain fortress and the village is a gateway toward other locations in the game world. This transitory place allows the player to take a breath and get ready for the next adventure (Wei et al., 2010).

Game space in the chronotopical or operational view

The operational structure is formed by characteristics that shape spatial operations by regulating and patterning movements, corresponding with Zoran's level of chronotopic structure. In games, being interactive, the plot is dependent on predesigned structure as well as player navigation and interaction. Zoran suggests that synchronic and diachronic relationships are the two main concerns for the level of chronotopic structure. Synchronic relationships detect the opposition of motion and rest, whereas diachronic relationships deal with movement through directions, axes, and powers through notions such as "routes, movement, directions, volume, simultaneity, and so forth". (Wei et al., 2010)

At any given moment, characters and objects are in one spatial state: movement or rest. Some characters or objects can move between spaces while others stay in one space. The question of synchronic relationship can therefore be articulated as "what is attached to one space, what not?"

Characters attached to one space become the "background" of the space, part of the context, especially when not interacting with the player. When players interact with these characters, the plot can change locally, and the range of that character's mobility and interaction determines the magnitude of the change. Characters that can move with greater range can play a more significant role in plot development, hence they are often the main characters that grow with the plot, along with the avatar. (Wei et al., 2010)

A path between locations can be unidirectional or bidirectional; the latter being reversible. Axes are the principal paths connecting major events and actions that take place. In role-playing games, players usually must move along the axis to progress by pursuing the main quest but are also allowed to explore the world and interact on side quests that follow paths branching out from the main axis. This is often structured with Murray's rhizomes, which is a "tuber root system in which any point may be connected to any other point". The tuber represents the axis, whereas the roots are the paths of side quests. (Wei et al., 2010)

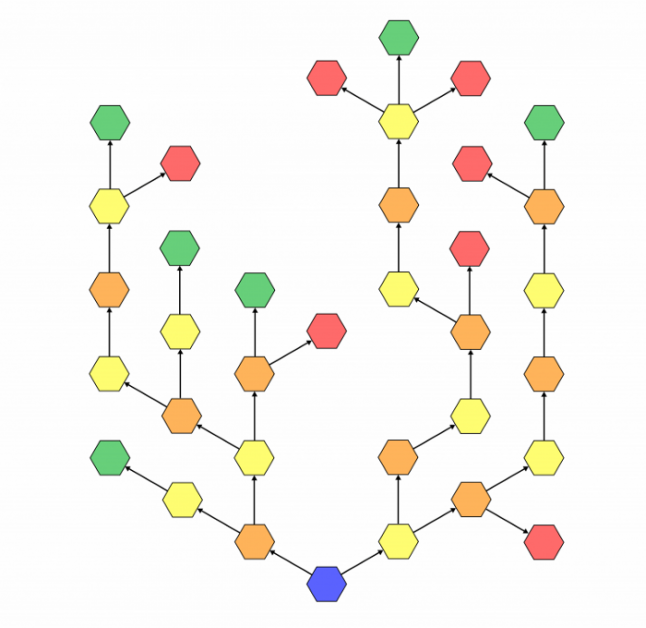

One of many forms of this rhizome structure is presented by Van De Meer(2019) as in what he calls trial narrative, side-questlines branch to lead either to a dead-end or back to the main story.

Figure 14: Van De Meer, A. (2019). Structures of choice in narratives in gamification and games. UX collective. https://uxdesign.cc/structures-of-choice-in-narratives-in-gamification-and-games-16da920a0b9a

Similarly, Van De Meer proposes the "open-world tree narrative", a structure that can typically be seen in complex RPGs.

Figure 15: Van De Meer, A. (2019). Structures of choice in narratives in gamification and games. UX collective. https://uxdesign.cc/structures-of-choice-in-narratives-in-gamification-and-games-16da920a0b9a

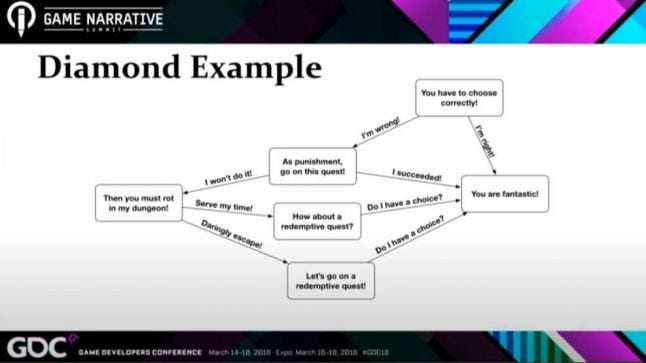

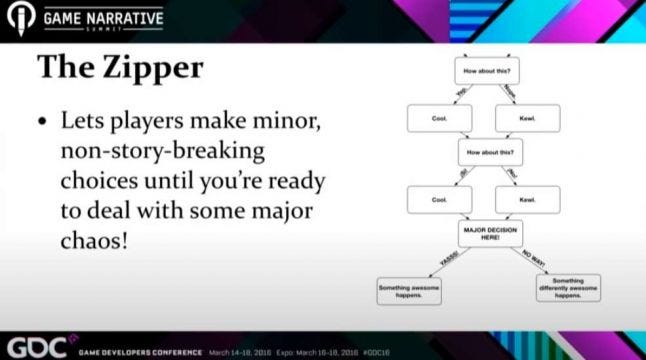

Jay Taylor-Laird(2016) explains a categorization into diagrams, amongst which he describes the notable rhizomes as "diamond" and "zipper", among others. The diamond diagram, according to the speaker, is often criticized for the lack of agency but can have some benefits such as unlocking sidequests or rewarding or punishing the player for the chosen path.

Figure 16: Taylor-Laird, J., (2016). The Shapes in Your Story: Narrative Mapping Frameworks. Game Developers Conference.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Xrsn2HBs6w

The "zipper" shape allows to only branch the story when strictly necessary while providing a completely authored sense of agency. An example can be seen in Black Desert, where we face many choices that have little effect on only the direct output of written text.

Figure 17: Taylor-Laird, J., (2016). The Shapes in Your Story: Narrative Mapping Frameworks. Game Developers Conference.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Xrsn2HBs6w

A more complex and dispersed mapping is Van de Meer's "adventure narrative", evoking the concept of choose-your-own-adventure books. According to Van De Meer, this kind of structure can be observed in larger story-driven RPG questlines like World of Warcraft, The Witcher, or pen&paper RPGs. In the author's words, "A recommendation for this choice is to build experiences that can be episodic in their nature. Each self-contained module experience is the episode in a larger ‘season’. [...]Doing it episodic means that you give players clear breaks, opportunities to reflect on experiences, and allowing them to re-enter the next session refreshed. "

Figure 18: Van De Meer, A. (2019). Structures of choice in narratives in gamification and games. UX collective. https://uxdesign.cc/structures-of-choice-in-narratives-in-gamification-and-games-16da920a0b9a

Van de Meer's article ends with a "sandbox structure", where the story is built up by independent blocks, therefore being completely up to the player and modular – think Minecraft, No Man's Sky, or on a physical plane, lego blocks:

Figure 19: Van De Meer, A. (2019). Structures of choice in narratives in gamification and games. UX collective. https://uxdesign.cc/structures-of-choice-in-narratives-in-gamification-and-games-16da920a0b9a

Game space in presentational view

Analysis on the presentational level focuses on how the game world is presented through patterns of visual, auditory, textual, haptic, and other cues, and how this presentation incorporates player actions. The first issue when presenting story space is the selection of spatial information to reveal on the screen. (Wei et al., 2010)

In the next paragraphs, we will treat some interrelated patterns used to present spatial information: Transitions, perspective, composition, saliency, and finally, sound.

The question of space segmentation also leads to the question of how to make the player have a fluid experience navigating through the subspaces. When subspaces are disconnected topographically, they can be displayed in the form of episodes or scene cuts. Otherwise, they may be connected to form the entirety of the game space in form of Murray's maze or rhizome. (Wei et al., 2010)

There are four common styles of transition between unconnected subspaces: direct cut, fly-through, cut-scene, and caption. For example, in Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, direct cut is used in most cases, however, in some instances, the game will play a fly-through sequence to familiarize the player with the new subspace. In other games, cut-scenes might be used as transitional means to introduce background information. In Fable II, captions simply tell the player they are to enter a new subspace. Another function of cut-scenes and captions is to entertain the player during loading time. (Wei et al., 2010)

Parallel action, as defined by Warren Spector(2013) refers to the psychological point of view difference between the objective viewer and the character. It is an editing technique used to display two or more simultaneous happenings at different locations, an example being the FBI raid scene in Silence of the Lambs(Paul, 2016). According to Spektor, while it is an understandably conventional cinematic technique, it is a bad practice for games as it "breaks the illusion of immersion, rests control away from the player who want to be the directors of their own experience".

Perspective can refer to two possible meanings: psychological or optical point of view. (Wei et al., 2010)

The psychological point of view locates attitudes and emotions(Wei et al., 2010). Psychological perspective, therefore, englobes emotional and motivational parity. Optical perspective refers to the visual positioning of the frame. The source of both perspectives can be subjective(from a particular character) or objective (from an external narrator or neutral viewer). Both perspectives are often intertwined, for example, a first-person perspective can reinforce the psychological perspective of the protagonist. (Wei et al., 2010)

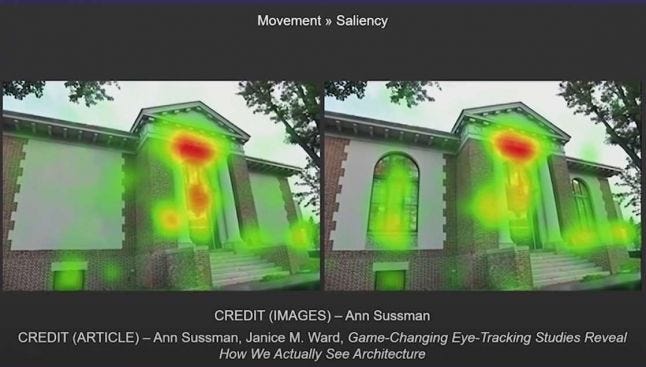

Composition is important for storytelling through the environment. Composition and camera can be used to draw attention to and from certain elements or to underline what is happening on the screen. As opposed to cinema, we can't control what the player is looking at, but we can handle the story by manipulating the environment instead of the view. (Bellard, 2019)

A central driver for composition is each object's saliency. Saliency refers to the attention-grabbing capacity of a scene object. It can be classified into two categories: bottom-up and top-down saliency. The former is about symbolism, attention-drawing shapes. Top-down saliency is dependent on the situation. For example, the abstract shape of a bottle or an apple will resonate more when we are thirsty or hungry, but there are also universal shapes that are always salient since they come from continuous necessities, like a weapon outline talking to the need for safety. Top-down is the type of saliency more active in task- or goal-oriented situations, while bottom-up is active in relaxed situations. (Bellard, 2019)

Figure 20: Bellard, M., (2019). Environment Design as Spatial Cinematography. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L27Qb20AYmc

Apart from presenting players the view based on the avatar's movement, the camera can also contribute to the game's interactive mechanism by guiding the player's attention. This is usually a direct cut or a zoom-in to an object or space (Wei et al., 2010). For example in dialogues in Black Desert Online, the camera either pans or hard-cuts to the point of interest depending on how far the point of interest is from the current focal point.

Sound is used to set the mood, create tension, and enhance the immersion of the game world. For example, in Fable II, ambient sound helps define the environment and shape the emotional tenor of progress through the game space. When a player is exploring a town, the background music is quiet and peaceful. When he or she is on the road, the music becomes loud and ominous, and when combat begins, drumbeats kick in to intensify the fighting mood. The dynamic design of the musical soundtrack effectively creates both narrative and gameplay tensions. (Wei et al., 2010)

Musical signature should be used to suit narrative structure, as composer Winifred Phillips(2020) explains. She compares two types of signatures on the examples of Assassins Creed: Liberation and Homefront: Revolution with the more episodic Little Big Planet. In the case of the former two games, we see a strong repetition where music is used as a mnemonic device, whereas the latter has a more episodical theme with more variation that underlines the different tone across environments since each has an entirely different story.

Music can be equally symbolic, and sound designers can become inspiringly inventive when it comes to creating systems that convey the story. It was Richard Wagner who coined the term Leitmotif ("leading motive") to refer to musical themes associated with a particular character, object, or action in the story. The technique of Leitmotif was first brought to cinematography by Ennio Morricone in the Dollar trilogy (For a fistful of Dollars, For a few dollars more, and The good, the bad, and the ugly), however the most well-known and eventually most complex adaptation of the notion was by Howard Shore in The fellowship of the ring. (Keane, 2021)

Doom composer Mick Gordon(2017) explains how he drew inspiration from David Bowie's production of Heroes in Berlin, where three differently instantiated microphones were used with gates to add reverb dynamically based on the input. Gordon applied this technique with further inspiration from the Doom concept art and storyline to design his system for Doom's musical theme. (Gordon, 2017)

Game sound also has unique functions to the medium, for example, to provide feedback for player interactions, like footsteps, or hints, like suggesting an incoming attack. Such auditory cues help players perceive the game space and imagine the off-screen space. (Wei et al., 2010)

Conclusion

Designers use planning algorithms to sequence events based on tension levels to ensure a strong dramatic and emotional tension arc. In Façade, the plot is divided into two levels of units: on a high level, the drama manager sequences dramatic beats based on the causal relationship between major events. These beats are crafted based on traditional dramatic writing, where each beat represents the smallest unit of dramatic action. On a low level, each beat contains a bag of joint dialog behaviors(jdbs). In response to player interactions, the beat dynamically selects and sequences a subset of jdbs. The system keeps track of the tension value of each beat and selects the next unused beat with the right tension value as well as other preconditions. Other systems focus more on player actions and goals, such as Barros' and Musse's Fabulator. The tension arc model here assumes that tension will rise when the player acquires more knowledge to move closer to the truth and adapts difficulty dynamically through the participation of NPCs. Thue et al. Propose a player modeling approach in PASSAGE that automatically learns the style of play preferred by the player, and uses the model dynamically to select events and deliver an adapted story, while grouping story events into phases of Campbell's monomyth.

No matter what principle is at work for sequencing the events, narratives carefully sequence and time story events to build dramatic tension into a strong emotional arc, ultimately basing plots on the Aristotelian model. (Wei et al., 2010)

Previous parts:

Part 1: Prologue

Part 2: Setting and Tools

Part 3: Freedom of Choice

Part 4: Structure and Devices

Part 5: Character Design

Next parts:

Part 7: From Theory to Practice

References

Claussen, A., (2017). Unpopular Opinion: All Narrative is Linear. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GWmEu7Yqrb0

Huaxin Wei, Jim Bizzocchi, Tom Calvert, "Time and Space in Digital Game Storytelling", International Journal of Computer Games Technology, vol. 2010, Article ID 897217, 23 pages, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/8...

Dinehart, S. (2019). Dramatic Play. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/dramatic-play

Lynch, Julie & van den Broek, Paul & Kremer, Kathleen & Kendeou, Panayiota & White, Mary & Lorch, Elizabeth. (2008). The Development of Narrative Comprehension and Its Relation to Other Early Reading Skills. Reading Psychology. 29. 327-365. 10.1080/02702710802165416.

Nitsche, M., 2007, Mapping Time in Video Games. Georgia Institute of Technology. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.68.1562&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Jenkins, H., in Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan (eds.) First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, Game (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004). https://web.mit.edu/~21fms/People/henry3/games&narrative.html

Juul, J., (2004). "Introduction to Game Time". In First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, edited by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan, 131-142. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2004. http://www.jesperjuul.net/text/timetoplay/

Ingold, J., (2018). Heaven's Vault: Creating a Dynamic Detective Story. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o02uJ-ktCuk&t=590s

Van de Meer, A., (2019). Structures of choice in narratives in gamification and games. UX Collective. https://uxdesign.cc/structures-of-choice-in-narratives-in-gamification-and-games-16da920a0b9a

Ruskin, E., (2012). AI-driven Dynamic Dialog through Fuzzy Pattern Matching, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tAbBID3N64A

NoClip, (2017). Designing the Quests on The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f2gVLzWpw_k

Ingold, J., (2017). Narrative Sorcery: Coherent Storytelling in an Open World. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZft_U4Fc-U

Sylvester, T. (2013). Designing Games. O'Reilly. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-games/9781449338015/ch04.html

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, December 15). chaos theory. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/chaos-theory

May, R. Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature 261, 459–467 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1038/261459...

Nekumanesh, K., (2016), DigiPen Institute of Technology, https://ubm-twvideo01.s3.amazonaws.com/o1/vault/gdc2017/GameNarrativeReview/Kaleb%20Nekumanesh%20GDCGameNarrativeReview.pdf

Hudson, K., (2016). Player-Driven Stories: How Do We Get There?. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qie4My7zOgI&t=483s

Takashi, I., Shingo, S., (2014). Understanding Christopher Alexander's Fifteen Properties via Visualization and Analysis. http://web.sfc.keio.ac.jp/~iba/papers/PURPLSOC14_Properties.pdf

Schell, J., (2018). The Nature of Order in Game Narrative. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E-qnXNUSUMA

Campbell, J., (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces, commemorative edition. Princeton University Press(2004). http://www.rosenfels.org/Joseph%20Campbell%20-%20The%20Hero%20With%20A%20Thousand%20Faces,%20Commemorative%20Edition%20%282004%29.pdf

Leitner, H., (2015). A Bird’s-Eye View on Pattern Research - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Diagrams-for-Alexanders-fifteen-properties-of-living-structures_fig7_305618476 [accessed 28 Feb, 2022]

Van De Meer, A. (2019). Structures of choice in narratives in gamification and games. UX collective. https://uxdesign.cc/structures-of-choice-in-narratives-in-gamification-and-games-16da920a0b9a

Taylor-Laird, J., (2016). The Shapes in Your Story: Narrative Mapping Frameworks. Game Developers Conference.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Xrsn2HBs6w

Spector, W., (2013). Narrative in Games - Role, Forms, Problems, and Potential. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8IIL9fVfFw8

Paul, J., (2016). Master the Hollywood Technique of Parallel Editing. The Beat. https://www.premiumbeat.com/blog/parallel-editing-hollywood-way/

Bellard, M., (2019). Environment Design as Spatial Cinematography. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L27Qb20AYmc

Keane, P., (2021). Howard Shore in The Lord of The Rings: How to use leitmotif technique to create a masterpiece?. TakeTones. https://taketones.com/blog/howard-shore-in-the-lord-of-the-rings-how-to-use-leitmotif-technique-to-create-a-masterpiece

Phillips, W., (2020). From Assassins Creed to The Dark Eye: The Importance of Themes. Game Developers Conference.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wk17Xn6MmDQ

Gordon, M., (2017). DOOM: Behind the music. Game Developers Conference.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U4FNBMZsqrY

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)