Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Following up on their profiles of the Commodore 64, Vectrex, Apple II, and Atari 2600, game historians Loguidice and Barton examine the lifespan of Mattel's cult '80s console the Intellivision, from Astrosmash to AD&D and beyond.

[Gamasutra's A History of Gaming Platforms series continues with a look at the Intellivision, a classic video game console developed by toy company Mattel and continued as an independent business for years after being dropped by that company. Need to catch up? Check out the first four articles in the series, covering the Commodore 64, Vectrex, Apple II, and Atari 2600.]

When Mattel released its Intellivision video game system in 1980, Atari knew it finally had a serious contender for the console crown. The Intellivision was more advanced than Atari's VCS (later known as the 2600) and featured distinctive software, clever marketing campaigns and sophisticated (though quirky) controllers. Mattel cultivated a unique and long-lasting brand identity, and it's not hard to find loyal fans of the system even today.

TYPICAL SYSTEM SPECIFICATIONS

Release Year 1980

Resolution 160 x 196

On-Screen Colors 16

Sound 3 Channels, Mono

Media Format(s) Cartridge

Main Memory 2KB

The Mattel company was founded in 1945. It was then primarily a manufacturer of picture frames and dollhouse accessories. After the introduction of the Barbie doll line in 1959, the company shifted its focus entirely to toys.

Barbie's unbelievable success swelled Mattel's coffers, and it soon diversified its lineup by purchasing smaller toy companies with unrelated product lines. Today, with well-known brands such as Hot Wheels, Barbie, and an ongoing series of acquisitions that include Fisher-Price and Tyco, Mattel is one of the world's largest and most successful toy makers.

In 1977, Mattel, under its Mattel Electronics line, produced the seminal Auto Race, the first all-electronic handheld game. It was crude by today's standards -- the visuals were represented by red LED lights and the sound consisted of simple beeps.

But the novel product was a huge success, spawning several other handheld games such as Football and Battlestar Galactica. These games sold millions and gave Mattel the confidence to move into the fledgling video game console market with the Intellivision Master Component.

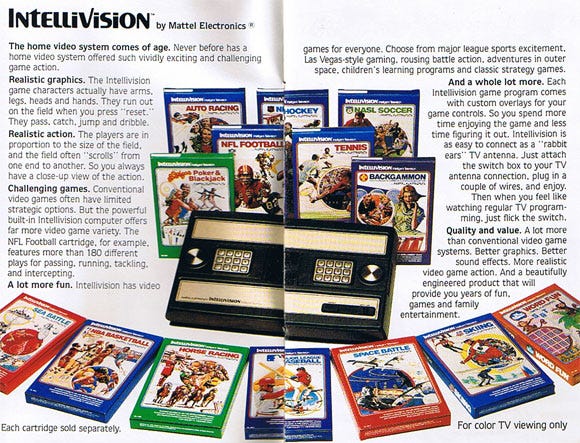

The inside of a 1981 Mattel Electronics Intellivision catalog, showing the original Master Component and various boxed games in their respective Network colors.

Mattel successfully test marketed the Intellivision in Fresno, California, in 1979, along with four games: Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack, Math Fun, Armor Battle, and Backgammon. The following year, Mattel went national, and quickly sold out the first year's production run of the popular systems.

Closeups of the infamous Intellivision controller. Despite allowing for an impressive 16 possible movement directions, the control disc was often criticized for its awkwardness with many games. Many add-ons of dubious value were created to purportedly enhance the control disc's functionality, like the Intellivision Attachable Joysticks shown to the far right.

The Master Component was a large, flat rectangular box that featured brown-and-gold detailing. The two controllers were permanently attached to the system. They consisted of thumb-operated control discs with 16 possible movement directions, which was twice the number of a typical joystick.

The controllers also had 12 button keypads with two action buttons on each side. The top two action buttons were wired together, so in actuality only three unique functions could be performed by the four action buttons.

Finally, the control disc and action buttons could not be used simultaneously with the keypad buttons; internally, they registered as the same inputs.

"The Intellivision Master Component will bring you many years of fun and excitement if you follow a few simple rules to keep it in good condition." (from the Intellivision Owner's manual)

Because of these quirks, Intellivision controllers were notoriously difficult to use. Although the multifunction controllers worked well for games requiring complex input, such as the genre-defining Major League Baseball (1980), they proved sluggish for games that required precise directional movement or timely button presses, such as the Nintendo arcade port, Popeye (Parker Brothers, 1983).

The heart of the Intellivision was a 16-bit microprocessor from General Instruments -- quite a step up from most other video game and computer systems at the time, which would continue to rely on 8-bit microprocessors for years. The Intellivision's sound chip was also impressive, allowing output of three distinct sound channels.

The machine also boasted a 16-color palette, but could only display eight simultaneous moving objects onscreen. Fortunately, clever programming could minimize this limitation on moving objects.

At first, Mattel farmed out game programming duties to a company named APh Technological Consulting. In 1980, an in-house development team was formed, which came to be known as The Blue Sky Rangers.

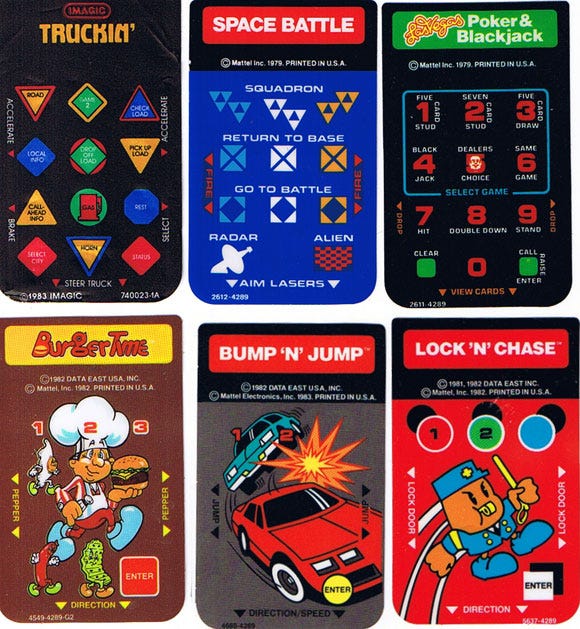

Some of the platform's famous controller keypad overlays were quite useful, like those for Truckin', Space Battle, and Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack, shown in the top row, while others, like Burgertime, Bump 'n' Jump, and Lock 'n' Chase, shown in the bottom row, were more for cosmetics than to serve a particular need.

Mattel advertised aggressively in popular magazines, and, like Atari, used television commercials as an important part of its marketing plan. For most of the Intellivision's original run up to 1983, Mattel employed writer George Plimpton, who became known as "Mr. Intellivision."

Plimpton's infamous advertisements helped promote the system and highlighted its technological advantages over Atari's Video Computer System (VCS, aka 2600). The advertisements often featured an Intellivision game -- usually a sports title that took full advantage of the system's capabilities -- right next to a woefully simplistic-looking game on the VCS.

Following Atari's example with its VCS, Mattel sublicensed the rights to distribute the Intellivision Master Component under different brand names, including the Sears Tele-Games Super Video Arcade, Radio Shack Tandyvision One, and GTE Intellivision.

Except for cosmetic differences, most of these systems were identical to the original Master Component. However, the Sears version offered detachable controllers which were a welcome improvement over the original model, as well as a different default title screen. In addition, as it did with the Atari VCS, Sears rebranded Mattel games under its own label.

However, despite the success and sophistication of the Intellivision, Mattel didn't always deliver on its promises. Mattel promised consumers the Intellivision Keyboard Component by 1981, which was to expand the Intellivision into a full-function computer.

Unfortunately, Mattel was unable to deliver the promised product to consumers in a timely manner, so the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) became involved after a series of consumer complaints.

Although Mattel was able to release a few units to test market and to those consumers who complained the loudest, the Keyboard Component was too costly for Mattel to reproduce on a large scale.

The Keyboard Component added an 8-bit 6502 microprocessor, expandable RAM, full keyboard, digitally controlled cassette drive for both data and audio content, expansion ports, and a printer port.

All of its features, in addition to the Master Component's own capabilities, made it more than a match for nearly any other stand-alone computer of the day. The 4000 money-losing Keyboard Components that were produced were not enough to appease the FTC.

All of its features, in addition to the Master Component's own capabilities, made it more than a match for nearly any other stand-alone computer of the day. The 4000 money-losing Keyboard Components that were produced were not enough to appease the FTC.

The FTC imposed daily fines, which prompted Mattel to move to an alternate plan with a much lower priced, but far less capable, computer expansion. It was not released until 1983.

"You know what the three big lies are, don't you? 'The check is in the mail,' 'I'll still respect you in the morning.' and 'The Keyboard will be out in the Spring." (Jay Leno at the 1981 Mattel Electronics Christmas Party, from the Intellivision Lives Website)

Modern gamers may be surprised that the ability to download and play games on demand was available for the Intellivision as early as 1981, when the innovative PlayCable adapter was introduced. Local cable companies could offer PlayCable: The All Game Channel to their subscribers who rented the hardware adapter and had a Master Component.

This setup allowed subscribers to quickly download individual games on demand. Although relatively popular in the areas in which it was offered, the idea was too ahead of its time for widespread acceptance and was discontinued by 1983.

With the Intellivision's growing success, Mattel Electronics was spun off as a separate company under the Mattel banner in 1982. In that same year, the company introduced the Intellivoice Speech Synthesis Module, which, after the Magnavox Odyssey 2's The Voice, was the second device of its kind for a video game console.

Through clever use of the built-in prerecorded sound samples and custom recordings loaded on demand for each game, every Intellivoice title had its own unique identity.

Although impressive even at the necessarily low sample rates, only five speech games were released. Poor sales of the Intellivoice spurred Mattel to provide a voucher for the module free by mail with the purchase of a Master Component.

To reduce production costs, Mattel Electronics introduced the sleeker and much smaller Intellivision II Master Component, a white and black unit with removable controllers and an external power supply.

Another "feature" was a secret validation check in the hardware that made third-party software inoperable. This check affected Coleco's 1982 arcade conversions -- Donkey Kong, Mouse Trap, and Carnival -- and inadvertently rendered Mattel's own Electric Company Word Fun (1980) unplayable. Fortunately, internal and external development groups soon figured out how to bypass the check.

Finally, a special video input added to the cartridge port made the System Changer possible, which allowed the Intellivision II to play Atari VCS games. All other Intellivision systems required internal modification to use the System Changer.

In 1983, the second computer add-on, the Enhanced Computer System (ECS), was released, retailing for less than $150. The ECS, like the System Changer, matched the styling of the Intellivision II, though it was compatible with all Intellivision models and the Intellivoice.

The ECS featured a detachable chiclet keyboard, an expansion box, and power supply. It also added an extra 2KB of memory, three extra channels of sound, two additional controller ports, and the ability to accept a standard tape recorder and a printer, the latter being the same as the one for the original Keyboard Component and Mattel Aquarius computer. A simplified version of BASIC was built in along with the ability to play musical tones.

An Intellivision II with ECS module, keyboard and music keyboard, along with an Intellivoice module.

Despite this flurry of activity, however, the future of the Intellivision's add-ons were anything but certain. Mattel Electronics had a management shake-up in mid-1983 and shifted its focus to software -- including for competing video game and computer systems -- rather than hardware.

This shake-up took priority away from initiatives such as the ECS and Intellivoice; only the Intellivision consoles would continue to receive advertising and software support. In the end, only a music keyboard add-on and five cartridges were released specifically for the ECS.

Following industry-wide losses from The Great Video Game Crash and too many costly dalliances in hardware development, Mattel Electronics was closed in January 1984, and its assets sold to a liquidation company owned by Terry Valeski, who was previously Mattel Electronics' Senior Vice President of Marketing and Sales.

In addition to handling old inventory, Intellivision, Inc., sold some complete, but previously unreleased cartridges.

Once most of the old Mattel Electronics inventory was sold, Valeski bought out Intellivision Inc.'s remaining assets from the other investors and formed INTV Corporation.

INTV Corporation hired former Mattel Electronics programmers to produce new Intellivision games. The company also released the INTV Master Component (called INTV System III and INTV Super Pro System, among other names), which was based on the easier to reproduce Intellivision Master Component, but with minor cosmetic changes.

Like Atari's 2600 Jr., INTV's system was marketed as a low-cost alternative to the newer and more powerful systems of the day, with the main console selling for less than $60 and many of the games for less than $20.

Like Atari's 2600 Jr., INTV's system was marketed as a low-cost alternative to the newer and more powerful systems of the day, with the main console selling for less than $60 and many of the games for less than $20.

INTV continued to produce new product up to 1990, when the company filed for bankruptcy protection, closing its doors for good in 1991.

During INTV's operation, Mattel did not remain idle. The toy company became involved in the video game industry again by affiliating with Nintendo in 1986.

Mattel not only produced new software and peripherals for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), but also handled distribution throughout Europe in 1987 and Canada from 1986 to 1990 on Nintendo's behalf.

Although most of the 1990s were quiet on the video game front for Mattel, in 1999 the company acquired a major computer software publisher named The Learning Company, but gave it away a year later after incurring heavy costs associated with the acquisition.

In 2000, in an effort to ride the growing wave of nostalgia for classic electronics, Mattel successfully reintroduced reproductions of their classic LED handheld game line.

In 2006, the company acquired TV Game manufacturer Radica and released the first true Mattel-branded console since the Intellivision II Master Component, the Mattel HyperScan.

The HyperScan combined card collecting and scanning with mostly fighting games and was marketed to "tween" boys.

Although not one of the two powerful successors to the Intellivision line that were in development during the Intellivision's heyday, the new system marked the first time an original pre-Crash company returned to the often fickle market of console video games.

Unfortunately for Mattel, the HyperScan failed to garner much interest and found its way to bargain and closeout bins shortly after release.

Today, several of the original Intellivision developers, known as The Blue Sky Rangers, run Intellivision Productions, Inc., which now owns the Intellivision branding and rights to most of the technology and games.

This group regularly releases TV Games and compilation software packs for modern video game and computer systems based on the Intellivision line of products, which many consumers still fondly remember and support.

Ultimately, 125 cartridge games were released for the Intellivision between 1979 and 1990, with a small portion requiring the Intellivoice or ECS add-ons.

Ultimately, 125 cartridge games were released for the Intellivision between 1979 and 1990, with a small portion requiring the Intellivoice or ECS add-ons.

A few additional homebrew games for play on a real system (or through emulation) have been released since 2000.

Many of the first 125 games feature some of the best graphics and sound for any video game system before Coleco released its more powerful ColecoVision, though gameplay speed often seemed a bit slower than many of its contemporaries.

Mattel generally grouped the games of its first software releases into categories called "networks," including Sports Network, Action Network, Gaming Network, Space Action Network, Strategy Network, Children's Learning Network, and Arcade Network, each with its own distinct box coloring.

However, Mattel's marketing discontinued the concept in late 1982 since most games fell into the Action Network category.

For the Intellivision Master Component's first two years, the system came packaged with Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack (1979), which played great one- or two-player versions of the title games, complete with an animated dealer.

This was followed by a newer pack-in, Astrosmash (1981), one of the system's more recognizable titles in which asteroids and other objects fell from the top of the screen and needed to be blasted.

The game featured a unique automatic dynamic difficulty control that allowed even novices to get high scores. Shortly after the release of the Intellivision II, a coupon for the excellent conversion of Data East's popular arcade game, Burgertime (1983), was included as well.

The Intellivision is most famous for its extensive range of quality sports games, including Mattel's own Major League Baseball, NFL Football, NBA Basketball, NHL Hockey, and PGA Golf, all released in 1980 and among the first games licensed from professional sports associations.

Most of these titles played well with the control disc and made good use of overlays on the keypad for more sophisticated in-game options. INTV would later commission renamed updates for many of these games that introduced enhanced features and support for single players, though without the expensive licenses.

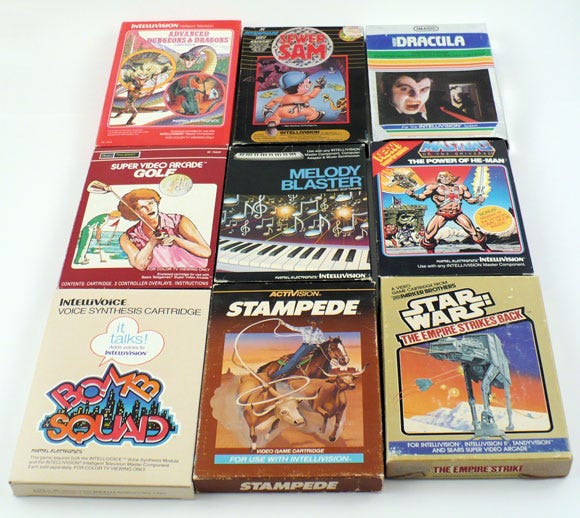

Besides sports and arcade licenses, Mattel gained the rights to many other properties, including Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, TRON, The Electric Company, and Hanna-Barbera cartoons.

Besides sports and arcade licenses, Mattel gained the rights to many other properties, including Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, TRON, The Electric Company, and Hanna-Barbera cartoons.

Although the strategy was to gain market share with familiar brands, Mattel's talented developers didn't actually follow the precedent of making lousy games and counting on the brand recognition alone to move product.

Mattel's lineup included the classic action role-playing games Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Cartridge (1982) and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Treasure of Tarmin Cartridge (1983), the educational The Electric Company Math Fun (1979) and The Electric Company Word Fun (1980), the popular action-packed TRON Deadly Discs (1982) and TRON Maze-a-Tron, and the ECS-enhanced Scooby-Doo's Maze Chase (1983) and Jetson's Way with Words (1983).

Mattel eventually shifted its development focus to mainly action games, but for a time, the Intellivision received several excellent releases that required cunning rather than quick reflexes. Besides entries such as ABPA Backgammon (1979), Horse Racing (1980), Reversi (1982), and USCF Chess (1983), there was the groundbreaking, critically acclaimed Utopia (1981), which enabled one or two players to rule an island in the face of constant man-made and natural disasters.

"Atari vs. Intellivision? Nothing I could say would be more persuasive than what your own two eyes will tell you. But I can't resist telling you more." (George Plimpton in a 1982 Intellivision magazine ad)

"Atari vs. Intellivision? Nothing I could say would be more persuasive than what your own two eyes will tell you. But I can't resist telling you more." (George Plimpton in a 1982 Intellivision magazine ad)

Most of the games set for release in 1983 were advertised as having "SuperGraphics." The label was intended to help bolster the Intellivision against attacks from the more advanced ColecoVision and Atari 5200 SuperSystem.

In reality, "SuperGraphics" was a marketing ploy, though the games did tend to use more sophisticated programming routines to generate better graphics and smoother game play than many of the system's previous titles.

However, the advertising did succeed in making the system's newer games seem a bit more exciting. This later batch of Mattel titles included the multiscreen Masters of the Universe: The Power of He-Man and Data East arcade translation Bump 'n' Jump.

Despite there being only five games released with the Intellivoice in mind, what was created was some of the system's more distinctive and sophisticated titles.

These include Space Spartans (1982), in which aliens relentlessly attack the player's spaceship and all-important starbases; Bomb Squad (1982), in which the player must follow voice prompts to disarm a terrorist's bomb; and B-17 Bomber (1982), which simulates a World War II bombing run; TRON Solar Sailer (1983), in which the goal is to decode an evil computer program.

The was also the ECS-based World Series Major League Baseball (1983), which was one of the first multi-angle baseball games, with its fast-paced gameplay based on real statistics, play-by-play with the Intellivoice, and the ability to load and save games and lineups from cassette.

Unfortunately, the rarity of the hardware combination allowed only a few gamers to experience programmer Eddie Dombrower's knack for simulating the Major League Baseball experience -- at least until the release of his popular Earl Weaver Baseball for the IBM PC and compatibles and Commodore Amiga computers four years later.

The advanced ECS-only World Series Major League Baseball (1983) took a different visual approach than other Intellivision baseball games, with multiple camera angles versus a single overhead view.

In 1983, the remaining ECS cartridge lineup was released. These titles included Mind Strike, a challenging, feature-rich board game for one or two players; Mr. BASIC Meets Bits 'N Bytes, which taught computer programming basics through three games and an illustrated 72-page manual; and Melody Blaster, a musical version of Astrosmash and the only other title besides the built-in music program that made use of the music keyboard add-on.

Unfortunately, while additional titles were in development before Mattel stopped supporting the ECS, no software took advantage of the additional controller ports for four-player gaming.

Third-party software support got off to a slow start on the Intellivision, with Mattel's attempts to lock out developers through the release of the Intellivision II. Besides Coleco, Activision, Atarisoft, Imagic, Interphase, and Parker Brothers all released cartridges for the system after 1982.

Although many of these were ports from other systems (mostly the Atari VCS), console exclusives found their way to Mattel's platform as well. These exclusives included Activision's Happy Trails (1983), which required a player to create new trail pathways by sliding jumbled pieces into place, and Imagic's Dracula (1983), which cast the player in the title role as both vampire and bat.

Imagic was particularly prolific on the platform, releasing an additional seven exclusives, bringing its final total to 14 titles.

These included Microsurgeon (1982), which featured lush visuals and allowed the player to navigate a patient's blood stream to cure illnesses, and Swords & Serpents (1982), an action-packed dungeon crawl that featured one- or two-player simultaneous game play as a white knight and wizard.

After Mattel Electronics closed in January 1984, the newly formed Intellivision, Inc., bought all remaining inventory for major toy store and mail order liquidation, including the remaining supply of cartridges from the Intellivision's third-party software providers.

With sales going well for the streamlined company, Terry Valeski decided to try marketing new games. These games included World Series Baseball (now supporting one or two players), Thunder Castle (action role-playing), World Cup Soccer (one or two players), and Championship Tennis (one or two players).

The first two games were completed at Mattel Electronics but never released, and the last two were completed by a former Mattel Electronics office in France; it had previously been released only in Europe by Dextell Ltd. The success of these new releases spurred Valeski to buy out Intellivision Inc.'s assets and form INTV Corp., to more aggressively pursue new Intellivision releases and reprints.

To save money, the company's new releases and reprints were produced with thinner boxes, contained no quality controller overlays (or, when absolutely necessary, reduced-quality overlays), featured cartridge labels and instructions that were printed in black and white, and often failed to renew licenses, necessitating a name change for the affected titles.

Despite intense competition in the reinvigorated video game market, INTV held its own until 1990, releasing 21 additional games in total, six of which were coded from scratch rather than built off pre-existing code. These six originals included sports games Chip Shot Super Pro Golf (1987), Super Pro Decathlon (1988), Body Slam! Super Pro Wresting (1988), and Spiker! Super Pro Volleyball (1989), and arcade translations Commando (1987) and Pole Position (1988).

The INTV System III featured nearly the same design as the original Master Component from Mattel.

For such a long-lived system line that sold more than three million consoles, the Intellivision's homebrew market is rather weak compared with many of the other prominent video game systems of the era.

New hardware has thus far been limited to low production run cartridges that allow loading of ROM images and assist with programming, such as Chad Schell's Intellicart and Cuttle Cart 3.

New game releases appear slowly and have been mostly uninspired, though some of the latest games are starting to make interesting use of the Intellivoice or the three extra sound channels provided by the ECS, as well as better programming techniques.

At this time, Intelligentvision is perhaps the most prolific publisher of homebrew cartridges for the Intellivision, taking great care with the color packaging and overlays, and releasing puzzle and strategy games such as Stonix, Minehunter, 4-Tris, and Same Game & Robots.

With a decade of releases in its mass market prime, Intellivision systems and variations are easy to find and relatively inexpensive, often selling with many games and an Intellivoice for well under $50, though care must be taken that the controllers are in working condition. The ECS add-on is rarer and often goes for about $70. The music keyboard add-on often goes for a little more than the ECS alone.

The Intellivision can be an easy and fun system to collect for with a variety of loose and boxed games readily available for purchase and play on the various systems.

Since the Intellivision Keyboard Component had such a limited production run and many were recalled, that particular add-on is among the rarest items for any system. As expected, the software is even rarer and comprises the BASIC Programming Language cartridge and the Conversational French, Crosswords (I-III), Family Budgeting, Geography Challenge, Jack LaLanne's Physical Conditioning, and Spelling Challenge cassettes.

Besides the TV games and official Intellivision emulation compilations released by Intellivision Productions for modern platforms, and select game availability on the computer-based GameTap subscription service, a variety of other unofficial emulators are available that can deliver a good approximation of the real system experience. These emulators include Bliss, Intv, and Nostalgia, with many also doing a good job of emulating the functionality of the ECS and other add-ons.

The Intellivision had new games in development right up to the closure of INTV, with the unfinished classic computer conversion of Choplifter!, shown here, and the finished, but unreleased, Deep Pockets: Super Pro Pool & Billiards, both featuring 1990 copyright dates.

While dwarfed in popularity and nostalgia by the legendary consoles from Atari and Nintendo, Mattel's Intellivision was a solid contender for its time and home to many impressive and highly playable games, particularly in the sports genre. The platform's innovative add-ons and associated software make it a desirable target for any serious collector.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like