Xenoblade Isn't As Good As You Think

Xenoblade was lauded as the harbinger of a JRPG renaissance, but its proponents may be seeing the game for what they want it to be, rather than what it is.

This article is cross-posted at http://flashyreview.com/2013/01/2012-year-of-the-lackluster-jrpg/

Xenoblade Chronicles was the undisputed hero of 2012’s JRPG scene, and that is a travesty.

The game deserves credit on many accounts: its fast travel system subdues the unruly vastness of its environments; being able to complete quests without returning to, or even meeting the quest-giver is a great way to streamline grind; the skill system provides a fair number of options; the voice-acting is competent, and conversations flow naturally – seldom does the player wait for spoken dialogue to catch up to its written counterpart.

Yet I balk at the popular inclination to declare this game innovative, let alone the latter-day savior of the JRPG genre. Too many accolades have been laid at the feet of this bog-standard IP. Xenoblade Chronicles’s design is comprehensively hampered by clutter and convention.

The user interface is the most egregious instance of clutter. The Wii-Mote-and-Nunchuk control scheme is beleaguered with commands, and many critical functions (targeting, camera control) require multiple buttons to be pressed or held. This is unforgivably cumbersome when you’re also trying to run or fight at the same time. Menus are also a hassle. A single button press activates a menu bar, which allows the player to cycle to select from several options while still moving around. At first glance, this appears to be a useful setup. However, in order to access any useful information, the player has to make one or two more selections, which inevitably lead to more traditional “pause-state” menus. So, not only does this introduce extraneous clicks each time the player wants to access the menu, but if he happens to have the menu bar open while running about, he has to cancel out of the menu bar before initiating combat actions. All too often, this results in the player getting smacked around because he thought he was going to attack, but opened a sub-menu instead. Furthermore, once the full menu is open, the navigational shortcuts are confusingly arranged, and require either all-too-frequent hand stretches to press the “1” and “2” buttons, or endless manual cycling through scads of items.

Across the board, Xenoblade has too much stuff lying around. You pick up a staggering number of useless items in playing through the game, usually in the form of little blue motes of light scattered at random across the environments. Most are meant to be sold, or used in gem crafting. That’s all well and good, but do there really need to be sixty different kinds of bug wings available to be crafted? Does each one make the world that much richer, or confer so finely nuanced a mechanical benefit? Of course not. This bevy of collectibles serves only as a perfunctory offering to the “Skinner Box” design ideology that no game designer professes to like, but everyone includes in their games these days.

The clutter creeps into the quest system as well. Yes, there are excellent mechanics in place to expedite the streams of meaningless fetch-and-kill sidequests. But why do these quests exist in the first place? They contribute nothing to plot or character development. They are a buffer, used to pad the play experience and create the illusion of a richer world by filling it up with junk.

These flaws might be forgivable if Xenoblade contained some truly revolutionary ideas, but in fact most of its mechanics are tried and tired, even if they have been given a glossy finish. The combat system is the most obvious offender in this regard. The “party meter” introduces some interesting dynamics, but combat is otherwise based on a typical MMO model. You control one character, spam your skills, wait for them to cool down, lather, rinse and repeat. Some skills gain bonuses based on how the character is positioned in relation to the target: this is a convention as old as the MMO, and doesn’t add much in the way of depth. The Break/Topple/Daze mechanic is fresher, but also fairly shallow – you can only damage some enemies when they’re toppled or dazed, so you topple or daze them. End of story.

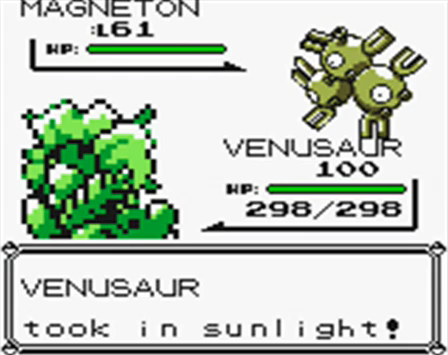

Even the game’s clairvoyance mechanic, the lynchpin of its status as an innovator, is a new package on a very old idea. In the end, it’s not substantially different from this:

Or this:

Things have been charging up for big telegraphed deathblows for a long time in RPGs. The main difference in Xenoblade is that any enemy can do it, and the mechanics in place to defend such attacks revolve around a few specific skills (ie the Monado’s Shield ability) rather than a broad array of tactics.

Finally, Xenoblade follows a tradition that is not so much a convention as an unfortunate characteristic of many JRPGs: bad storytelling. This is not so much an issue of plot, as of presentation. As an example here is an excerpt from an early “Heart-to-Heart” between the nerdy protagonist, Shulk, and the his oafish friend, Reyn:

REYN: Oh yeah! You remember that time? You know, that one time!

SHULK: When we had that big fight?

REYN: That’s the one. It’s easily the biggest bust-up we’ve ever had. In all the years I’ve known you, nothing else has come close.

SHULK: It was bad all right. I’m just glad we made up afterwards.

REYN: You know, for such a big argument, I don’t even remember what it was about.

SHULK: We were really young. It was probably just some silly kid thing.

REYN: You’re probably right. Hey Shulk…do you ever think about it? Without me bringing it up, I mean.

SHULK: I think about it sometimes. If we never had that argument, I don’t think we’d be friends now.

REYN: That’s just what I was thinking. We must have said some pretty harsh things to each other. But it was worth it, right? It’s why we’re such good mates now!

SHULK: Yeah, it was definitely worth it. You know, it’s funny how we think alike sometimes. I’d have figured you were still angry.

REYN: Nah, not anymore. But you did get on my nerves a bit back then. You were just too clever man. It got under my skin.

SHULK: And I thought you were just this big dumb brute. Hey, I guess that’s what we were arguing about.

REYN: Yeah, that sounds about right.

It would be literally impossible for this conversation to have conveyed a greater quantity of completely obvious, generic information. This is the biggest fight Reyn and Shulk ever had, the foundation for their relationship, and they can’t remember one specific detail about it! However furiously they characters might wave their arms and bob their heads, this type of interaction amounts to a feeble excuse to fill the screen with pink hearts that tell the player how much he’s supposed to care about these two vapid fools.

This article is written with a caveat: I have only played Xenoblade for about fifteen hours. I know what’s-her-face gets killed. I know there are plot twists. I just can’t bring myself to care. I want to like this game, I really do. I want it to be the revolution that so many people have taken it to be. I want a JRPG that redefines the genre and lifts it to new heights. But if we start projecting our desires onto the games we play, instead of seeing them for what they are, we take a great risk. We risk damaging the critical faculties that will allow us to recognize that game comes down the pipeline, or (better yet) to make it happen ourselves.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)