Who We Are: The Dynamics of the First Person Character

Should your first person player character speak or not? This post explores the choice between giving the player character a voice or having them be "silent" through the lens of more traditional media.

While working on the story for a first person shooter, I ran into, what I had thought to have been, a basic and simple question: should the player character speak or be silent?

While working on the story for a first person shooter, I ran into, what I had thought to have been, a basic and simple question: should the player character speak or be silent?

At first, I thought if I wanted a “real” character, I would just give them a voice like Booker Dewitt (BioShock Infinite) or Henry (Firewatch). But then there are characters like Gordon Freeman (Half-Life) and Corvo Attano (Dishonored), where we can see that it’s possible to characterize the player character even if they do not speak. And this doesn’t even begin to consider characters that skirt the gray area like the player android in The Talos Principle and Stanley of The Stanley Parable, where the player character does actually have a voice but one that is representative of the player. So I decided to do some research into the first person point of view model to help me answer the question and understand its ramifications on the narrative and gameplay.

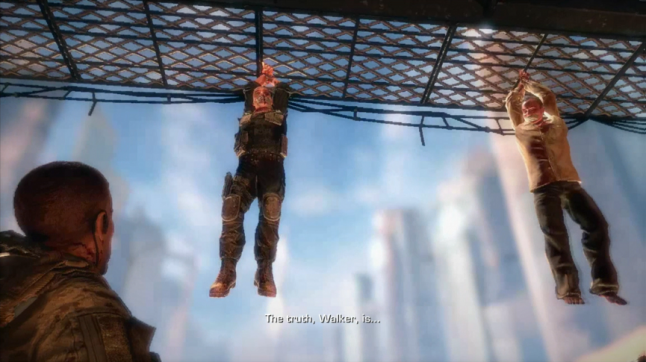

In a more traditional medium like literature, it’s clear that the first person POV forces the reader to experience the story through the consciousness of the narrator. They can be telling a story where they lie at the center of it, or they can be telling one in which they are in the periphery. But irrespective of who the story is about, the story itself becomes inseparable from the character telling it. The narrator’s diction and, more importantly, choiceful presentation of information imposes a certain perspective--a certain, specific way of viewing the scene at hand (I found that the unreliable narrator is one that explores this idea greatly).  Mimicking literature’s style of delivery would appear to require the player character to have a voice or at least some means of communicating their point of view. I couldn’t think of any great first person game examples, but Spec Ops: The Line uses some of these techniques, albeit through visuals and sounds, to create the same level of subjectivity. While one could imagine the same techniques being reused for a first person POV, I think it’s worth noting that this choice in stylistic delivery may not work tonally for every game.

Mimicking literature’s style of delivery would appear to require the player character to have a voice or at least some means of communicating their point of view. I couldn’t think of any great first person game examples, but Spec Ops: The Line uses some of these techniques, albeit through visuals and sounds, to create the same level of subjectivity. While one could imagine the same techniques being reused for a first person POV, I think it’s worth noting that this choice in stylistic delivery may not work tonally for every game.

Moving onto a seemingly more relatable medium like film, the first person POV isn’t exactly prevalent. Hardcore Henry (2015) is one that certainly applies, but that style of presentation isn’t transferrable (when’s the wave of FMV first person shooters coming). .jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) There are techniques that film uses to make certain camera shots feel like they’re first person in order to bring out important aspects of the scene, like using a shaky hand camera during a chase sequence, but they are only used sparingly and are not representative of the entire film’s point of view. So I needed to search elsewhere, outside of the typical movie.

There are techniques that film uses to make certain camera shots feel like they’re first person in order to bring out important aspects of the scene, like using a shaky hand camera during a chase sequence, but they are only used sparingly and are not representative of the entire film’s point of view. So I needed to search elsewhere, outside of the typical movie.

The most similar viewpoints in film to video games are actually found in our daily news, dreaded infomercials, and documentary-style interviews. To start with, newscasters and infomercial salespeople both share a common ground: they both look directly into the camera. When they speak, it gives the semblance that they are speaking directly to us. With documentary-style interviews, the camera often views the interviewer and the subject from the side but at eye level. It feels like we are sitting in the room with them, listening to their conversation. In film, these first person POV techniques (including ones like the shaky hand camera) are used to bring us into the story’s space and make us feel like we are a part of what is happening on-screen.

The first person POV in games is a natural expansion on film’s techniques for directly bringing us into the story’s world. As the player character, we occupy a physical space and aren’t a sort of limited omniscient camera that follows the character around. It can often feel like a documentary-style interview when you watch NPCs stand around and talk to each other, or like a infomercial salesperson when an NPC looks you in the eye and hands you a fetch quest. The newscaster/salesperson/interview style translates well into the silent protagonist types, like those found in Half-Life, The Talos Principle, and The Stanley Parable, where we can only observe the events as they unfold and are generally powerless to change the predetermined plot. In many regards, having a silent protagonist is similar to watching a context-sensitive film.

When I started to look at speaking player characters who have their own realized motivations that drive the plot, I slowly came to the realization that they’re actually an expansion on literature’s model of a first person narrative. Like with silent protagonists, we still remain as an observer but the difference lies in the change in the dynamic between us and the player character, thus affecting how we view (and experience) the diegetic world. The likes of Booker DeWitt (BioShock Infinite), Ethan Winters (Resident Evil 7), and Henry (Firewatch) encourage us to experience the world as they see it, and the player character becomes a “real” character, whereupon the goals of the game/player now emerge from or are expressed by the player character.  How the world pushes back against the motivations or desires of the player character becomes an integral part of drawing us into the player character’s perspective. At the same time, we still have to coexist with this character throughout the entire game, making it doubly important for us to empathize with them. We essentially have to embody the character and be strongly aligned in terms of motivations. If there is no such alignment or it skews the wrong way as a result of some repulsive action on the part of the player character, the game risks losing us (the topic of cognitive dissonance is an interesting one). Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2’s “No Russian” level is a great example of sidestepping a possible moment of misalignment since the player is not actually forced to kill anyone to complete the level.

How the world pushes back against the motivations or desires of the player character becomes an integral part of drawing us into the player character’s perspective. At the same time, we still have to coexist with this character throughout the entire game, making it doubly important for us to empathize with them. We essentially have to embody the character and be strongly aligned in terms of motivations. If there is no such alignment or it skews the wrong way as a result of some repulsive action on the part of the player character, the game risks losing us (the topic of cognitive dissonance is an interesting one). Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2’s “No Russian” level is a great example of sidestepping a possible moment of misalignment since the player is not actually forced to kill anyone to complete the level.

This was when I realized that first person narratives with silent protagonists, who don’t have their own expressed motivations, do actually share similarities with literature’s other kind of narrator, the peripheral narrator. Since the player character cannot speak, games have found other means of constructing player motivation. Half-Life 2 shows us that it can be as simple as making empathetic characters that interact with us, like Eli and Alyx, or that it can go as far as empathizing with an entire resistance because we’ve experienced hostile characters like City 17 and the Combine.  Like the peripheral narrator, the primary character of the story will appear to be some aspect of the world that is beyond the player character (like Elohim or Milton in The Talos Principle). However, unlike the peripheral narrator, the story arc with silent protagonists in most current games has become more about how only the world changes as a consequence of our actions rather than how we as the player should change as a result of the story’s events. The distinction here lies in the fact that games do not often require us to undergo some psychological change in order for the story to be “complete” (The Talos Principle is a great and interesting example that does have this requirement).

Like the peripheral narrator, the primary character of the story will appear to be some aspect of the world that is beyond the player character (like Elohim or Milton in The Talos Principle). However, unlike the peripheral narrator, the story arc with silent protagonists in most current games has become more about how only the world changes as a consequence of our actions rather than how we as the player should change as a result of the story’s events. The distinction here lies in the fact that games do not often require us to undergo some psychological change in order for the story to be “complete” (The Talos Principle is a great and interesting example that does have this requirement).

To answer the question “Should the player character speak or not?” is to answer the question “Who is the story about?”. Choosing between either the motivated protagonist or the silent protagonist ultimately means choosing between an empathetic character or an empathetic world. With an empathetic player character, the narrative will generally explore a more personal story where the world is more or less an extension of the player character built specifically to challenge their worldviews. Gameplay-wise, this means that the player character will often be making decisions, mainly story-based ones, on the player’s behalf, like Booker in BioShock Infinite. On the other hand with an empathetic world, the narrative becomes more about the world beyond the player character, where their role within that world is much more significant than the player character themself. It then becomes necessary to include elements of environmental storytelling layered with the inclusion of at least another character who we will empathize with. Gameplay-wise, the world will need some way to incite the player, like “pick up the can” in Half-Life 2 or the assassination in Dishonored. It’s certainly possible to develop empathies for both, BioShock Infinite is a good example of this, but, even in BioShock Infinite, it’s still clear that Columbia, the characters, and even Elizabeth are extensions of Booker, created for the express purpose of challenging him.

- Stephen Trinh (@stephentrinha)

Take a look at: Ken Levin's BioShock Infinite interview with GameSpot

References:

Janet Burroway, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft 8th Edition (Chapter 8, Point of View)

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)