The Three Kinds of Story Games Can Tell

Ian Bogost's recent article for The Atlantic seemed to fundamentally misunderstand the medium. Let's react with positivity - and celebrate the 3 kinds of story that ONLY games as a medium can tell.

The Three Best Kinds of Game Story

Or: Why Is Ian Bogost is so salty?

The other day, Ian Bogost wrote a piece for The Atlantic entitled Video Games Are Better Without Stories.

Although this post is about positivity, adding to the discourse as opposed to trying to stifle it. By way of context though, let’s quickly look at the introduction to Bogost’s rambling, 2000+ diatribe, as it contains the most urgent warning sign that he fundamentally misunderstands the medium, and that you really shouldn’t let him upset you.

In this hypothetical future, players could interact with computerized characters as round as those in novels or films, making choices that would influence an ever-evolving plot. It would be like living in a novel, where the player’s actions would have as much of an influence on the story as they might in the real world.

There is so, so much wrong with that set up that I’m not going to start to unpack it.

What I want to do instead is offer something productive, something positive, as a counterpoint to Bogost’s petulant, baffling misunderstanding of the medium’s potential.

So let’s look at what I think are the three kinds of story which games can tell that no other medium can, at least not in the same way.

1. Linear/Game Authored

Simply put, linear narratives that are mostly authored by the game and its creators. Bioshock or most JRPGS are good examples. The story is both told to and experienced by us. It’s still unique and thrilling when done well of course because we’re living it, we have some agency, and we inhabit the protagonist in a very tangible way.

The best kinds of interactive narrative will offer us some amount of roleplaying. Take Kentucky Route Zero for example — nothing you do in the game will affect the outcome or change any kind of variable within the game, but at every point you have dialogue options that allow you, the player-character, to choose the why and the how do I feel.

They are of course the most numerous kind of narrative-game, not without good reason — the risk is relatively low of anything going badly wrong to the carefully authored story!

1.i Non-linear, Game-authored

The recent glut of ‘walking simulators’ are slight variations. The linear narrative therein is usually discovered and interpreted in a non-linear fashion by players. Make no mistake however, they are still effectively non-interactive, linear stories, but there is something to be said for making the player work a little to piece it together. Namely, the Ikea effect.

2. Player-Authored/Driven

In games such as Animal Crossing or the recent indie equivalent Stardew Valley, the player is not taxed by gameplay difficulty or skill ceilings, but is instead engaged by choices to make within their own story. Do you dive straight in to perpetuating Tom Nook’s socialist utopia, or live as a hermit in the most ascetic of cartoon shacks? Do you marry the girl next door, or the postman, have a human baby or devote your energies to the fluffiest livestock?

Even though these games are often referred to as systemic, which they are, the human mind is adept at creating stories from interlocking events, whether there is real causality or no. The stories are no less valid as a result. It is up to the player to eke out their own, usually more placid narrative from these kinds of games, and they do, perennially and enthusiastically.

To some extent, MMORPGS fall into this category, as they rarely have much of a proper central storyline (excepting Final Fantasy XIV). Instead, it is very much up to the player to get deep into the role-play, creating an on-going story of their own trials and tribulations as they progress, geographically and in power/aptitude.

3. Emergent

One of the trendiest forms of game narrative, these are stories that occur when a complex set of mechanics and systems react to player choice. Elder Scrolls and GTA are two series that encourage this in exceptional ways, despite having a central linear narrative. We’ve most likely all created our own stories within these open worlds through curiosity or a montage of semi-causal events.

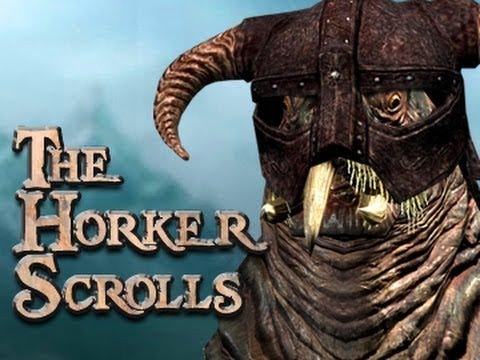

One of my personal favourites in Skyrim was the epic, artic mega-fauna battle royale I got myself into while trying to see how far North the map extended. I went through enough Horker and Ice Troll blubber in that battle to feed the Nordic populace for years. That mini-narrative was extrapolated by my own mind from systems in the game reacting to my in-game choices, and these are probably some of the most memorable gameplay moments many of us have experienced.

Usually the term ‘emergent gameplay’ is the one actually bandied around, often in tandem with ‘procedural generation’, but I don’t think anyone genuinely gets excited by, say, the 100th boss-orc battle in Shadows of Mordor. No, the beauty of the nemesis system, and emergent gameplay in general, is in the stories it lets us tell ourselves. Math may create it all (and to Math I am in reverent, confused awe) but it should do so in service of story. Some recent, high-profile releases have got this oh-so very backwards.

3.i Ambient/Storysense

Not quite emerging from complex systems necessarily, these are stories told in an ambient manner. Such games are often dense with storysense as with Ueda’s masterpieces, in which virtually no speech occurs, and very few ‘events’ actually take place. Yet, everything from the animation to the architecture, the richness of the lore bubbling away beneath the surface, creates a magical kind of immersion.

Inside is another recent paragon of this category. Are we entering a golden age of storysense?

No discourse on ambient storytelling would be complete with mention of Journey. I mean, what more, fittingly, need to be said? There’s nothing before or since that is quite like it. Indeed, each example in this category alone could support a book about their story-telling techniques.

3.ii Meta

My favourite example of the meta-story games can tell is Eve Online. Literal books/comics have been created out of the stories that have emerged in-game. These epic events, such as in-game ponzi schemes and spies infiltrating rival guilds over the course of years, are all made possible by communication between human player, outside of the game itself. It’s real life writ large, played out through polygons but containing every whit of human ingenuity and cunning. It’s part emergent, part player-authored, but I think by dint of it requiring so much extra-game communication it requires its own sub-category and honourable mention.

Conclusion, of sorts.

I was initially annoyed when I read Bogost’s article. I may even have made a sarcastic tweet. But let’s be real for a second — there will always be naysayers. For those of us in the business of telling stories, in games or otherwise, we must calmly say to ourselves and each other: “fuck that noise”. There are incredible stories to be told, not just by writers, but by every part of a game’s team.

Stories are like fibres in a rope — the more we have, even if they’re of different kinds, the stronger the whole endeavour becomes.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like