The suprising scream of learning

Have you ever wondered how surprises relate to our emotions beyond physical reactions and the horror genre? Would you like to know how a narrative constructor thinks in the creation of curiosity, surprises, and suspense?

Previously posted on Narrative construction by Katarina Gyllenback

Have you ever wondered how surprises relate to our emotions beyond physical reactions and the horror genre? Would you like to know how a narrative constructor thinks in the creation of curiosity, surprises and suspense and how the cognitive vehicle of narrative works?

A few weeks ago I got a secret text message from my child's friends about setting a date for a surprise party. We set a date and I promised to not say a word. I also gave myself a reminder to not interfere as an adult as it would ruin all the fun with the planning of the surprise. A week before the party I got a new secret text message about a cake they should bring which made me wonder from a nutritional perspective (a typical adult thing to do) if they needed anything else to eat. “That would be great,” they replied. “At what time?” I asked, thinking that they had plans to go somewhere else. “Anytime that suit you best,” was the answer. It was then I understood that we were going to host a few numbers of guests for dinner, which required that I had to secretly forewarn the rest of the family. Two days before the surprise party I received a new secret text message from the friends asking if they should bring pillows and covers. It was then the penny dropped and I got the full picture of what the surprise party was all about. One could say that the whole family got surprised but in two different ways.

My child got a shock, as we know it from the horror genre: scream, hard to breathe, tears and laughter. Since the plan was (which I also learned a day before) that I was the one to keep my child away from home when the friends prepared for the surprise, the rest of the family had experienced extreme noise and excitement in the air from the group. When approaching home I was sending secret text messages telling how much time they had left before we would come through the door: “10 min…5 min…still 5 min…2 min…” I may have exaggerated the countdown a bit. It had almost been unbearable to reside at home for the rest of the family, especially two minutes before our entrance when all the friends had to get in control of their emotions and be quiet.

Impressively it was completely silent when we came home. It looked as expected, peaceful and normal when walking through the door. Even though I knew what would happen I got scared as well when the friends did a classical and perfect jump-scare, as we know it from the horror genre, and screamed “Surprise!”

Since it's hard to keep track of what actually happens in a noisy inferno of a surprise I have italicized four important keywords through the text: learn, understand, control and expect. This is so we can study from a cognitive perspective the subtle and quiet mind activities when exposed to a surprise.

If I say that a surprise is a condition of learning, does that mean we should scare people to make them learn? Absolutely not! Considering the unhealthy level of emotions when exposed to a surprise, learning by scaring is not an option. But if a surprise is a state of learning, does that mean that people don’t learn if we don’t hear them screaming?

The reason why we don't scream every time we understand (apart from Archimedes that cried Eureka) is because the evolution has equipped us with a memory. So when we interpret the information we know from our prior experiences and knowledge that a car is a car, and so on. But if there would be a giraffe on the top of the car’s roof it would attract our attention and make us curious. We wouldn't cry Eureka, but we would certainly start speculating about the giraffe. Our curiosity combined with our emotions is what creates a motivational engine to learn. But if we scare without care, the motivational engine will be turned off (or be redirected). So if we like to understand what makes the engine of motivation to spin in a positive direction we need to go beyond the physical reactions and look at the narrative construction from a cognitive perspective. This is to understand what makes people not turning off a game or leaving the cinema when exposed to horror.

As a narrative constructor, you always think in terms of learning and how people will interpret the information. The reason for this is that our goal is to undercut the understanding in order to create surprise, curiosity and suspense. If thinking of a surprise and how it involves emotions, one could say that putting someone on suspense, which we were exposed to when we slowly learned about the surprise party (step by step) the similarities with the process of learning can be seen. What the narrative constructor actually does is to withhold and forward information in order to make people hypothesizing. When doing this, the narrative constructor keeps the emotions going like an engine. You hold back and speed, hold back speed…

Even if the friends didn’t deliberately put the family in suspense, the slow-paced learning made our emotional engine go because our expectations were revealed to be incorrect. This, in turn, made us re-evaluate our hypothesis, and then we started all over again to see if our new hypothesis were correct.

The risky part of the emotional engine at the surprise party was that someone in the family could have said “no” as the expectations went in another direction. What I mean is that you really have to be careful when handling expectations, as someone can get disappointed and decide to take control of their emotions and learning and say "no thanks". Since the new information changed the direction of involvement, it could have clashed with other expectations (like having a calm evening, night and next day). But what saved the surprise party was the engine of motivation, which we know as a curiosity, and that we wanted to see how our expectations would fall out by the means of seeing the younger family member being exposed to something unexpected. We also knew due to our prior experiences and knowledge that it would be appreciated and fun, which became a part of our hypothesis and made us willing to accept the changed direction (note, about the ability to imagine someone else's emotions will be explained in a later post).

So even if it was hard to see or hear the families' emotional inner drive when we learned about the upcoming surprise party, the emotional engine could, on the other hand, be seen and heard from the excited group of friends. From my position in the front seat row, standing behind my child at the surprise moment, I could see the friends' emotions of uncertainty and worries when they tried to understand if their hypothesis had fallen out as expected when watching their friend scream, cry and laugh. They looked like they genuinely regretted not taking a course in first aid. But as soon as they saw the expectations were fulfilled, by the means of seeing their friend happy, a feeling from the control of understanding calmed down the emotions.

If you look at the will to learn/understand and how it connects to our emotions, it’s important to keep in mind when you like to engage people that the cognitive engine of understanding is constantly on as we don’t like to not understand. Thankfully we know how to adjust and control this in everyday life because of our prior experiences and knowledge. But as soon as something unfamiliar and unexpected occurs, the engine of anxiety will be "turned on" until we understand and feel in control again. This also means that we can be pretty fast at coming to an assumption (and in the worse case, it can lead to prejudices). But by looking at learning as “anxiety-driven”, this is also what a narrative constructor does when balancing and controlling emotions in the creation of curiosity, surprises, and suspense.

Since controlling someone’s emotions doesn’t sound like a nice thing to do one can wonder what is good or not a good way to handle the cognitive vehicle of narrative?

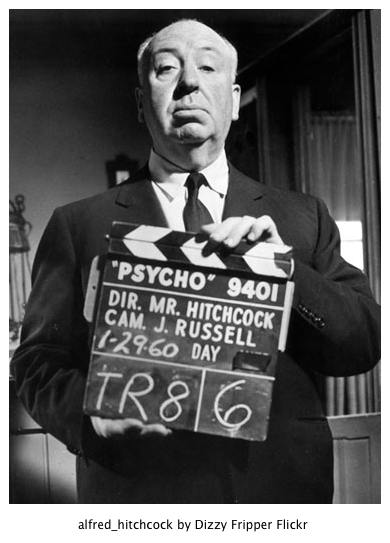

If looking at Hitchcock and how he can get away with scaring people, the answer can be found at the time of exposure to the suspense. Also, what Hitchcock does is to let people get in control of their emotions by letting their hypothesis be proven correct according to their expectations. But if you don’t let people understand and constantly present unfamiliar and unexpected information, which makes the emotional engine to start over and over again in order to understand, that is when the narrative construction is used in a bad way. So from a narrative perspective on cognition, I would surprisingly rather see Hitchcock elected for a four years term in the office as he would understand what it means to take care of people’s expectations by not leaving them driving on an endless road of speculations.

Since my aim is to tell how surprises and emotions work beyond physical reactions and horror genres, I hope you are ready to investigate the final piece from the surprise party that will explain what happened to my child who screamed, cried, laughed and had a hard time to breathe.

Notice. If you intend on reading or viewing “Game of Thrones” for the first time then you can stop reading here and give me a note and I’ll write you another version of the ending.

For you that saw all seasons of “Game of Thrones”, you probably remember the scene from the sixth season when someone said: “Hold the door!” Did you try to tell someone afterward that hadn’t followed the series about the feeling you experience? It was even hard for me. Therefore I have chosen to tell about the surprise party and what happened to my child to explain the narrative construction behind the line: “Hold the door” and why a surprise can quietly intoxicate the mind and body.

If we return to the surprise party and right after the shock; the evening, night and the morning after, my child did backtracking in memory. Everything that my child had found odd in people’s behavior before the surprise party was traced and revealed. While doing this all my child’s hypothesis about the friends and how they acted strangely, was proven to be correct (and where I proudly managed to not reveal myself, but it may be because adults are always expected to act strangely).

The same cognitive backtracking also happened in “Game of Thrones” when the line: “Hold the door” surprised people. And the most amazing thing was that the backtracking of five seasons happened almost instantly. This tells something about the speed of our minds when learning but it also says something about how hard it is to see, hear or measure reactions unless you understand narrative construction from a cognitive perspective.

Now to the moment of truth. The reason I chose the surprise party to explain the cognitive vehicle of the narrative is due to an issue related to our prior experiences and knowledge. Since there are a lot of people that think of narrative construction and stories as bound to ancestors of media, we often see a lot of text and the canonical story format (exposition, complication, and outcome), as we know it from films and literature, applied to games. This is at the expense of understanding the cognitive vehicle of the narrative. When considering at what speed we are thinking and by knowing how emotions relate to our learning, it’s no wonder that we like to stay with familiar structures and templates. Since the narrative is not media-specific I hope the surprise party served as a reality check that will enable an exploration of narrative construction as a cognitive vehicle beyond story structures, genres, and physical reactions.

And just as a reminder, never scare without care.

by Katarina Gyllenbäck

Illustration by Linnea Österberg

If you don't like to be put in suspense, please visit Narrative construction to learn more about narrative as a cognitive vehicle in the design of meaningful experiences.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like