The Seven Deadly Sins of Writing Interactive Fiction

Those are my personal guidelines when making text games, and they come from a place of frustration with some common practices in the genre.

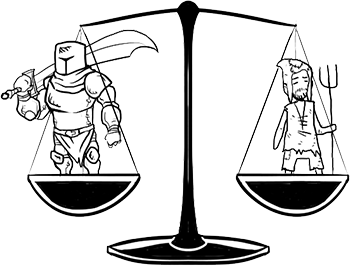

1 - Railroading (The Sloth of Not Branching)

The shortest distance between two points might be a straight line, but it rarely is the most fun. Even if you add curves or bends to the path, your players will feel like passengers being propelled in the same direction unless you present them with a fork in the road from time to time.

Players want the power to choose where they are going, regardless of what that destination may end up being. They want to feel like their choices matter, and that a different decision somewhere along the road could have led them to a completely different path.

Even if the ending they get is not the best possible one, they will want to play your game again and again, propelled by curiosity or a desire to make things right this time. As long as you manage to captivate them and give them the opportunity to learn from their mistakes, they will be eager to make new ones.

And it doesn’t hurt to let them hop off the train and wander around the wilderness from time to time either.

2 - Compulsive Choices (The Lust for the Perfect Option)

It doesn’t matter how many choices you present to your player at once; if one of those options is obviously better than all the others, then it is no choice at all.

The best choices are those that present equally viable options, with different approaches to the same problem. Multiple alternatives should make sense in the context, even if they end up failing or giving unexpected results.

This, of course, doesn’t mean that all choices need to work for all characters. Some variables should rightfully impact the success rate of a course of action, and, understandably, a barbarian might not be able to sweet-talk their way out of a problem as well as a bard, for example.

But you shouldn’t stick to a single good option per character type all the time, or you will be limiting your player’s choices. Put your imagination to good use here, and think hard about all the possible ways to solve a problem, and why they would or wouldn’t work in each situation.

Otherwise, you run the risk of coming off as lazy. And lazy authors inspire lazy players, and lazy players might not want to keep playing your game. Instead, give your players all you got, and they will owe up to the consequences of their decisions and keep coming back for more.

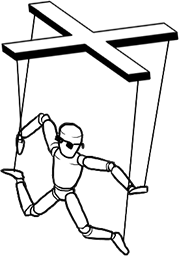

3 - Puppeteering (Being Envious of Your Player)

A player doesn’t want to feel like a puppet on a string, dancing according to their master’s movements. If anything, they want to be the puppeteer.

Sometimes, when an author wants something specific to happen in a game, they will make it occur regardless of the player’s actions. Even worse, they will make the main character do something to trigger those events without any previous input from the player.

But if the initial trigger wasn’t authentic, then it just feels like things are happening because the plot demanded it. And if the plot demanded it to a point where it had to seize control of the main character from the player’s hands, maybe it shouldn’t be happening at all.

As an author of interactive fiction, you have to learn when to let it go. The main character is not yours anymore; the player owns it from the moment they start playing the game.

Don’t be the puppetmaster. Be the strings, the control pad, the person who made the marionette—not the one who’s controlling it. Hide yourself from the audience and help create the illusion that the puppet is alive, instead of reminding the player that it isn’t.

4 - Ventriloquism (The Greed of Owning All The Words)

Similar to Puppeteering, this is when the main character does something without the player’s input. In this case, it refers to instances where they speak on their own.

Sometimes, it only diverges from an initial dialogue prompt, as the choice selected by the player ends up not reflecting what their character eventually says(this is the case in some big franchises, such as Mass Effect or The Witcher). Others, it happens even more gratuitously, as entire exchanges transpire without any of the dialogue coming out from the main character’s mouth being something the player chose to speak.

While the second is evidently more intrusive than the first, I find that, more often than not, both break immersion and undermine roleplaying. If you’re not limited by art assets or voice actors, then perhaps you shouldn’t be sparing dialogue options. Make that brilliant banter you came up with be spoken by secondary characters instead, or turn it into the consequence of a specific choice. The more content, the better.

The players will feel like they have earned it, and the entertaining value will remain the same.

5 - Indifference (Neglecting the Pride of Your Players)

Don’t neglect your players. I find that self-reference is the glue that keeps a good story together, and from time to time, you should make an effort to acknowledge what they have accomplished so far.

Instead of just handing achievements, make it so that other characters comment on their actions, be it good or bad ones. Don’t just hamfist commentaries of their deeds into the game either; look for the perfect opportunities to mention something, and try to take into consideration the possible repercussions as well.

Be it a single dialogue line, or an extra paragraph, a new option, a different description, or even a unique scene… as long you present it, and do so efficiently, your players will know you have not forgotten about them, and the feeling will be mutual. They will not forget about your game either.

6 - Time-Wasting (The Wrath of a Sudden Death)

Don’t waste your player’s time. Avoid making deathtraps that are only there for shock value. Give subtle warnings beforehand; things that may not appear evident at first but will make a lot of sense in hindsight.

And if your game is long and branchy — and unless it is against a fundamental principle of its design) — , try adding a save feature. Let players experiment and take risks without having to restart the game from the beginning. There should be enough varied content in your game to warrant multiple playthroughs without having to rely on cheap deaths.

7 - Misremembering (A Gluttony of Consequences)

If Indifference is not properly acknowledging a player’s actions, then Misremembering is directly contradicting them. Logical failures and inconsistencies are well too common when developing nonlinear or branchy games, and having beta testers to help you find them is an invaluable asset in making sure that all consequences are appearing where they are supposed to be.

Be it for strings, booleans, or numbers; every time you create a variable, you are also assuming a responsibility. You’re making a promise that you, as an author, will keep the record straight for your players. That you will not disrupt their experience by giving them anything other than what they deserve, and that you will always be there, watching and keeping the record straight.

Those are the guidelines I followed when making my latest game. I’m not trying to enforce them as the only possible way to design a piece of interactive fiction(numerous excellent games do stuff I said to avoid), but they do reflect my personal preferences both when playing and designing games of this kind.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)