Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The Quest for Honest Feedback

You are not a rare and precious snowflake, but your playtesters will treat you like one.

[This article by Ryan Henson Creighton is re-posted from the Untold Entertainment blog, which is awesome.]

Over the past few days, i've had a few colleagues run me through quick play-throughs of their mobile games. Maybe you've been there? A fresh-faced developer looks at you with his big doe-eyes, inclines his head, and asks plaintively "can i show you my game?"

Oh ... crap.

Your butt muscles clench. What can you say? "No?" It's not usually practical to make an excuse and bolt for the door. Face it: you're going to have to play his game. And you hope to God it's good.

It's Not Good

When the game isn't good, you say it's good anyway. Why? Because you just can't possible look into those dewy Disney bunny eyes and crush this poor developer's dream. He's worked hard on this game, you can tell. Probably spent a lot of time - and perhaps a lot of money - on it. And anyway, games are so subjective, right? Someone's bound to like it. So you look at him and say, somewhat non-committally, "yeah. Yeah. It's ... it's good." And perhaps, while in the depths of your treachery, you may even add "i like it." You think you are doing this because you are a good person, and because the developers' feelings matter more than honest feedback. In reality, you are doing this because you are a dirtbag.

Truth Is Love

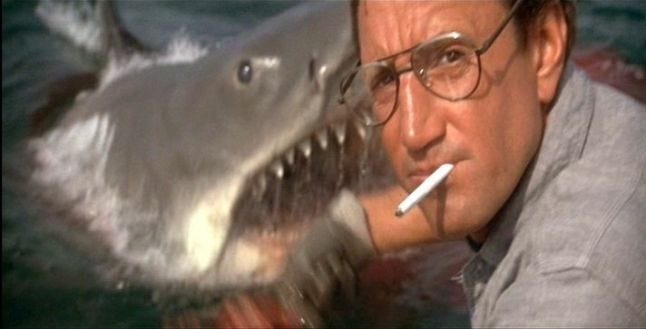

There is nothing more poisonous to a developer than falsely positive feedback. If you're developing a terrible (or lacklustre, or uninteresting) game, but your passion has blinded you to its shortcomings, the encouragement you field from players and colleagues will only hurt your cause. It's like asking people "hey! What do you think of my shark-feeding skills?" and the people all say "yeah. Yeah. It's ... it's good. i think you should stick your arm even further into that shark's mouth. You're not quite there yet. Keep going."

We're gonna need a bigger game.

The result is that the developer keeps feeding the dangerous shark until he gets his arm bitten off at the shoulder, he wanders away from the shark in disinterest, or he grows old with the shark and eventually dies, never having ventured to feed another, perhaps nicer animal. (And at this, my metaphor crumbles spectacularly.)

The Snowflake Factor

When a game has obvious flaws, why are we so reticent to give constructive criticism? It's because we're all rare and precious individualist snowflakes, and the emotional pain of failure (and the ego-bruising that it entails) is the worst affront we can possibly suffer. We would never want to inflict that pain on other people - the stinging truth that our creation is mediocre and uninteresting, or just not very special.

Because we're all so thin-skinned ... because spirited debate is now viewed as distasteful, and criticism is now chalked up to "one's own opinion" and easily disregarded ... we need to get craftier about the way we solicit feedback from people. Here's what i've recently suggested to the colleagues who asked me to play their games (i haven't tested this myself, but i'm very interested to know if it works):

Do not present the game as your game. Present it as your friend's game. Say "my buddy's making this game, and he asked me what i thought of it. i know him too well to give him good, impersonal feedback. Could you take a look?"

The potential problem is that for some people, the Snowflake Factor may even extend to arm's length. You may not get honest feedback on your game, because the player doesn't want to hurt your imaginary developer friend's feelings. FFS. That's okay: i got this.

Present your game like this: "Hey. My friend is making this game, and he wants me to invest in it. He says i'll get a cut of the game's profits when it's released if i give him some money to finish it. Can you play the game and tell me what you think?"

You'll never change into a real developer at this rate.

The Snowflake Factor is now working in your favour. The player's need to protect your feelings, since you're standing right in front of him, now overrides his need to protect your imaginary arm's-length friend's feelings. With this tall tale in place, you will likely get the constructive feedback you need. And if the player asks if he, too, can invest in the game, you'll know you've got something good on your hands.

In this age of developer delicacy and easily-bruised fruit, tactics like these are crucial to soliciting honest opinions from people who should know better.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)