Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The Narrative Engine Driving Ice-Bound: A Novel of Reconfiguration

Learn about the innovative narrative engine driving Ice-Bound, an indie game that interacts with a physical book using augmented reality. Also, some details on how the devs tackled the thorny problem of combinatorial content authoring.

What is Ice-Bound?

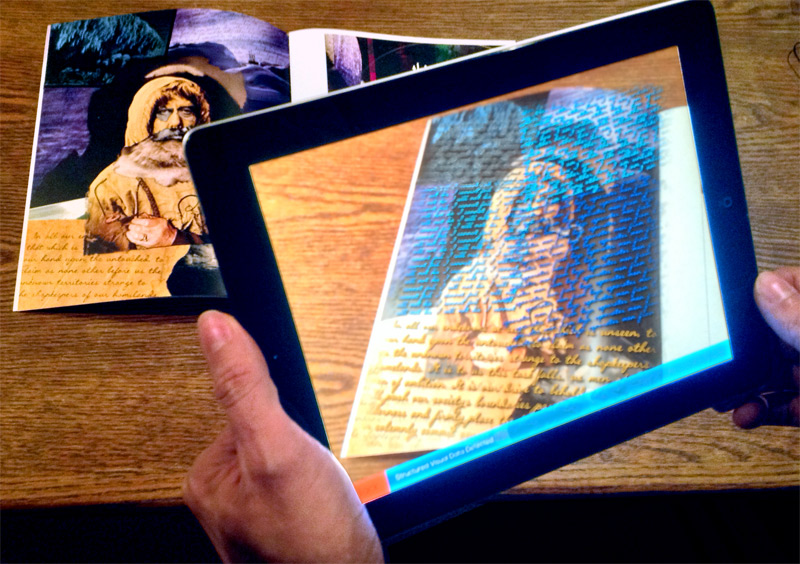

Ice-Bound is a combinatorial narrative game that uses augmented reality to drive interactions with a physical printed book. The centerpiece for player interaction is the reading and rearranging of different stories the system creates, using a custom narrative engine that earned it the 2014 Best Story / World at IndieCade. It's coming out in early 2015 for PC and iPad.

We're taking pre-orders through Kickstarter until November 5th, so if you're looking for more general information about the game, that page is a good place to find out more. What I wanted to talk about here, though, is combinatorial narrative.

Combinatorial? That's like...branching, right?

Not quite. Combinatorial narrative is when several sections of text can be combined in different ways to yield significantly different stories. This differs from branching, "Choose Your Own Adventure" models, because the possibility space explodes much quicker, so much quicker in fact that it's infeasible to try tactics like hand-writing every possible state the story can get into.

Lots of games, like Bioware’s Mass Effect series or TellTale's The Walking Dead focus on making stories reactive through branching models by offering a couple discrete choices (usually between two or three options) and making that choice pay out in a big way (or making it appear to do so). But there’s a devilish double-bind designers run into with this approach:

If you want the choice to matter, you need to write a really good story to reflect that, but...

if you want to write a really good story, it’s probably going to be by hand, which means

you’re going to be spending time producing stuff that most people won’t see.

A lot of games try to compromise for this by reducing the impact of choices to simply adding flavor. Meaning: you must crash-land your spaceship into the asteroid to steer it away from Earth. Can't change that. But you can change the way that plays out. You don’t change the story per se, but more change the flavor of the context for those narrative events. This makes for a great initial game experience that seems really responsive, but on a second playthrough usually yields complaints from players once they realize they aren’t changing the substance of the experience, just the wrapper.

Yet trying to change the events themselves is super labor-intensive. Star Wars: The Old Republic charged headlong into the multi-linear fray, for example, putting a team of 12 writers full time on it for 2 years. The result was authoring more content than any of Bioware's previous titles COMBINED. So the costs are real. And sadly, most of that writing goes unseen by any given SW:TOR player.

With combinatorial narrative, we wanted to try getting more writing in front of the player, and deal with the fast-growing possibility space. We're just a team of two, so we have to be economical in terms of labor, and we want to maximize the exposure of the authoring we have to do. We also want to take advantage of the fact that, since we're just dealin with text, we don't need to worry about voice acting or other problems AAA titles might encounter. But...you can’t really just combine anything together willy-nilly, because you want to approach the kind of coherency hand-authored narrative has. So we also need some kind of structure so that the different parts fit together more seamlessly.

So what’s the structure?

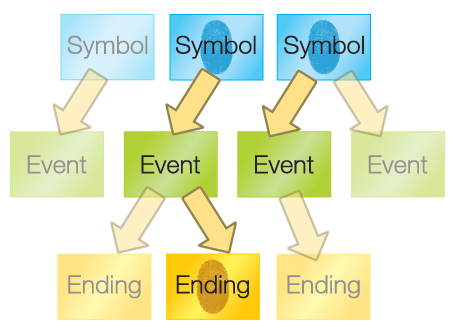

For Ice-Bound, we used three types of texts: symbols, events, and endings. Symbols are the scene setters, the smoking guns, the MacGuffins. It might mean a character is paranoid, or had a troubled childhood, or is pining for a lost loved one.

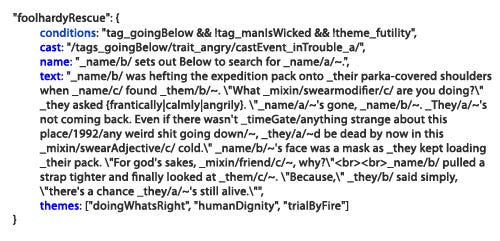

Events are texts revolving around the main action of the story. They have “pre-conditions”, which means they only activate under certain circumstances. For example, there may be an event revolving around a violent confrontation if a character is paranoid. But if the player deactivates that symbol and switches it to “pacifist”, it in turn deactivates the violent confrontation event, and activates a different event where the two characters have a reasonable discussion.

Endings work in the exact same way, except keyed off of events (usually). So by simply deciding which symbols are active, readers control the flow and outcome of each story. For us, it means we can build way more possible stories, that are far more tailored, but still write a relatively small amount of text. It also means a lot more of what we write gets seen, which translates into being more effective authors.

Soft-edged Puzzle Pieces

You can’t just combine text though. Well, you can but unless you’re making some kind of post-structuralist, collage narrative, you have to be sure there’s a through-line, a thread of context readers can follow. A light they can follow through the desert.

Defining that thread, that light, is tricky business. Fall into the trap of simulation, and you’ll want to make a model of everything that’s happening in the story. What if the object the main character picks up is the thing they set down on a table in the second event? What if the system knows things go on tables? Wait what is a table? Never mind…what if the system knows when two characters are in a room together, setting things on tables?

You can go down this rabbit hole, and many systems have tackled the problem, with varying levels of success. For us, we knew we wanted to keep the focus on interesting stories, without getting bogged down with simulating the space of the story. So wherever possible, we want to leave it to the reader to draw the line between the dots. It feels like cheating, but we’re not hand-waving the problem. We do want to make sure there is some baseline consistency.

To do that, we use a system of contextual expansion grammars. A grammar is simply a string of text that contains a symbol that tells the system to perform some sort of substitution of that symbol. But it might slot in text that contains another symbol, and thus trigger more expansions, containing additional replacements, ad infinitum. Also, each grammar replacement can execute code referencing the full state of the system to decide what text to produce.

A simple example is character casting. We use grammars like _characterWithTrait/feisty/ to make sure the right characters end up in the right scenes. We can get more complex though, like using different text based on how many other characters are present, using specific language for specific time periods (such as changing an “email” to a “letter” or a “telegram”), or even changing text based on the way the reader ended a previous story.

We can get really far in flexible authoring too by doing some simple thinking like “hey, this event requires a feisty symbol, so I know there’s a feisty character in here somewhere…” or “I know the character has had some sort of confrontation with their teammate because this ending requires that kind of event, so maybe it can reference that like this…”

So we author these chunks of story, these puzzle pieces, and soften their edges with grammars to make them relatively adaptable. It’s a delicate dance, writing something between text that can be used always, or only used once. We shoot to write text that can show up several times, with clever ways to make it adapt to each context so it feels more like it was written just for that context. And we make sure the conditions for each one, the bindings between symbol, event, and ending, are robust as well.

Responding to Player Choices Meaningfully

So now we have all this content, and it can be re-combined in different ways. One of the things this lets us do is react to player choices.

Ice-Bound is about creating a series of stories, and at the end of each story created you have to convince the AI character, KRIS, that the story should go that way. In order to do that, the player has to show him proof from the Compendium, the printed book that accompanies the game.

Using augmented reality, the player scans the Compendium, which reveals hidden content, in addition to clues about the story. It's another really compelling channel for game content that I could write a whole other article on, but our chief focus here is that each page is tagged with a set of themes, and the player is confirming through the act of scanning which themes they want to reinforce.

We take that information, and when moving to the next level, let that influence the types of options the player is presented with as their symbols to manipulate. In practice this means if a player is really into horror stories, by scanning in pages from the book about horror they are informing the system about this preference. In later levels, more of the symbols they work with will be tagged with horror themes, which will in turn give rise to stories based more around that theme.

Conversely, we can author content to hit wide swathes of game states by basing it off themes. One set of cards themed "horror" might introduce some sort of monstrous force loose in the station: these are also given the “monster” tag. We can then have ending fragments that require a “monster” tag to be already present: so, feeling in an actiony sort of mood, we might write a dramatic conclusion (perhaps involving a flamethrower) that could be the end to any of the various “monster” intros. This is some of what we mean when we say the system feels like playing with Legos: “monster” events become a block type that can attach to “monster” endings to produce something with narrative coherence. (We also do this in less melodramatic ways, too: creating emotional setups and payoffs involving a character dealing with loss, a romance, or a journey of self-discovery.)

Flexible Authoring

That's the system, in a nutshell. We also created a series of data visualizations in the course of authoring, to better help us understand what sets of triggers still need written events and endings, and how best to structure those triggers to hit the sweet spot between firing too often, and only firing once. You can find out more by checking out two papers we authored for Foundations of Digital Games 2014, one for the data visualization, and one that details the combinatorial system in more depth.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)