Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the latest Gamasutra-exclusive bonus material, originally to be included in upcoming book 'Vintage Games', the authors look at one of the most influential, but sonetimes underdiscussed video games of the 1980s - Braben and Bell's Elite.

[In the latest in a series of Gamasutra-exclusive bonus material originally to be included in Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton's new book Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the Most Influential Games of All Time, the authors look at one of the most influential games of the '80s -- one that hasn't perhaps had as much press as it deserves, in recent years, as Americans, and consoles, have been ascendant.]

Elite, released in the United Kingdom in 1984 and the United States a year later, was the first major entry in a genre now called the "space sim."

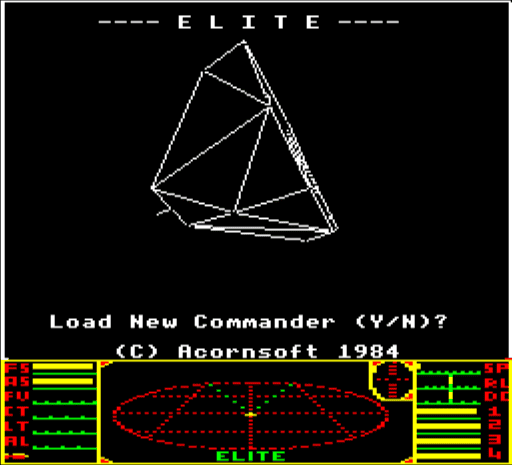

Developed by Ian Bell and David Braben for the BBC Micro, Elite made a big impact in the United Kingdom, the only territory where Acorn's BBC Micro and compatible budget-friendly Electron computers had a presence.

Bell and Braben's masterful coding for the original Acornsoft version extracted every ounce of juice from these modest machines, wowing gamers and reviewers alike.

Although publisher Firebird's ported versions may have been less groundbreaking than the originals, Elite still made an impact in the United States, becoming a fan favorite on the Commodore 64 and other popular platforms like the Apple II.

Indeed, in March 2008, Next Generation declared it the #1 best game of the 1980s, calling it "the spiritual predecessor of everything from Wing Commander through to the Grand Theft Auto series."[1] But what is it about Elite that deserves such high praise and justifies such bold claims?

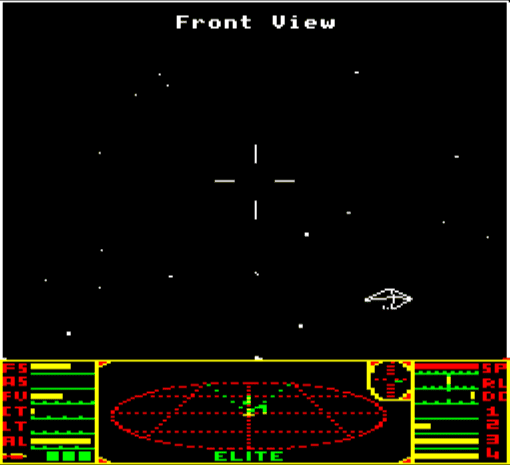

The player controls a single character in Elite. Similar to a CRPG, the goal is to slowly improve the character by purchasing ship upgrades and destroying enemy ships, which gradually raises the rating attribute from "harmless" to "elite." BBC Micro screenshot shown.

Although some fans exaggerate its novelty, Elite is actually a hybrid of two distinct genres that had been evolving since the earliest days of home computing: the space trading game and the flight simulator (a.k.a. the flight sim).

The space trading game can trace its origins back to games like Edu-Ware's Space (1978) and Empire I: World Builders (1981)[2] for the Apple II, as well as FTL's SunDog: Frozen Legacy (Apple II, 1984; 1985, Atari ST)[3] and Omniware's Universe series (starting 1984; Apple II, Atari 8-bit, and others).

All of these games offered many of the tropes seen in Elite. There are the same economic imperatives to sell cargo between and among countless planets, purchase upgrades for your ship, and the chance to battle as or against space-faring pirates.

One recurring theme across this genre is the open-ended "sandbox" style gameplay that is most often associated with the slightly more rigid Grand Theft Auto series (see book Chapter 9, "Grand Theft Auto III (2001): The Consolejacking Life") today; players are mostly free to choose their own way to accumulate capital and judge their own success at the game.

There is no one right way to play these games, and plots (if they exist at all) have little bearing. All of these games are highly detailed and complex, requiring comprehensive manuals and rigid study.

FTL's SunDog: Frozen Legacy, took a different approach than Elite by featuring a much smaller, but more detailed and interactive universe. However, perhaps FTL's most overlooked achievement was what they referred to as "ZoomAction Graphics," which was an innovative close-up view of the player's main activities that still provided the player a larger frame of reference. Back of the box for the more advanced Atari ST version shown.

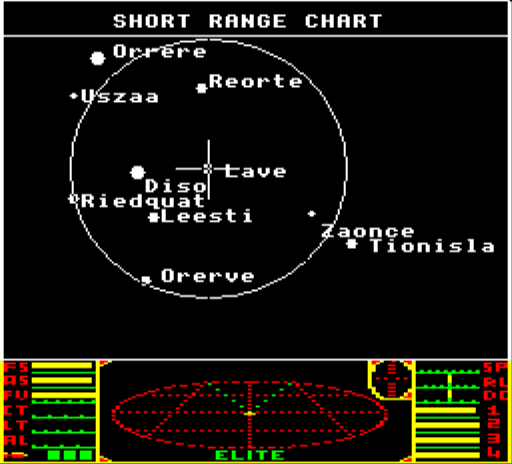

Besides its excellent implementation of wireframe 3D graphics, where Elite really set itself apart from these other space trading games was its procedurally generated universe, including planetary positions, names, politics, and general descriptions.

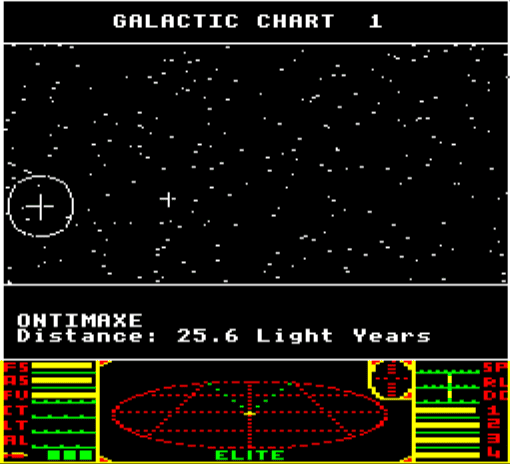

Although this procedural generation technique would have allowed for trillions of different galaxies, in order to hide the limitations of the game's algorithms while still creating an impressive universe, the final design was purposely limited by Acornsoft to eight galaxies, each containing 256 planets.[4]

The only major downside to this technique was the occasional generation of difficult-to-reach star systems that a predesigned universe could have avoided.

This chart shows one of several galaxies that the player can explore in Elite.

[1] See http://tiny.cc/DpKCJ.

[2] Empire I: World Builders was the high-resolution graphics-enhanced replacement for Space when Game Designers Workshop sued Edu-Ware for copyright infringement.

[3] Although SunDog: Frozen Legacy was much smaller in terms of the size of its universe than Elite, it one-upped its more popular contemporary by featuring an innovative drag-and-drop windowing interface and the ability to exit the ship and explore populated, interactive cities.

[4] See http://books.guardian.co.uk/extracts/story/0,,1065455,00.html. A few other games in the same basic genre, such as the more RPG-like Starflight (1986, Atari ST, Commodore 64, Commodore Amiga, and others) from Electronic Arts, would also use procedural generation to great effect to create its hundreds of explorable planets. Of course, Will Wright's creature creator and life simulation, Spore (2008), also from Electronic Arts, takes this technique to its ultimate level with content that is almost entirely procedurally generated.

Flight sims, of course, offer a much different but still similarly complex and open-ended gameplay: specifically, the freedom to fly through a fully three-dimensional space in real time (see book Chapter 8, "Flight Simulator (1980): Digital Reality").

Although some flight sims offer a campaign mode or even a linear narrative structure (take for instance, Cinemaware's 1990 Wings for the Commodore Amiga), most also offer a "free flight" mode that allows players to simply pilot the aircraft and explore the virtual world.

The best flight simulators are very realistic and detailed, and, like the space trading games, take a good deal of time and patience to play well.

Naturally, developers were quick to adapt the traditional flight sim to represent space flight, including Activision's Space Shuttle: A Journey into Space (1982; Atari 2600 Video Computer System, Atari 5200, and others).

Other notables include Edu-Ware's Rendezvous: A Space Shuttle Simulation (1982, Apple II), Mindscape's The Halley Project (1985; Apple II, Atari 8-bit, and others), Access's Echelon (1987; Apple II, Commodore 64, PC, and others) and Microsoft's Microsoft Space Simulator (1994, PC).

Games like Access' Echelon (box back for the Commodore 64 version shown) tried to not only build off the successful Elite model, but also to offer their own flourishes. In Echelon's case, these flourishes took the form of three different modes of play: Scientific (exploration), Patrol (exploration with combat), and Military (combat). Note that the LipStick voice-activated control headset was included to provide additional support for the Commodore 64's standard one-button joystick and acted as a second button.

The genius of Elite was to combine these two genres into a single coherent game: a space trading game based on a space flight sim. This blending of the two genres would quickly gain the new label "space sim," and it has spawned dozens of popular derivatives. A few recent releases include Digital Anvil's cut-scene heavy Freelancer (2003; PC), Dreamcatcher's Space Force: Rogue Universe (2007; PC), and Egosoft's X3: Terran Conflict (2008; PC).

Perhaps the most notable of the current generation is EVE Online, a massively multiplayer space sim released in 2003 for the Apple Macintosh, PC, and Linux platforms. Of course, older classics such as Origin's Space Rogue (1989; Apple II, Apple Macintosh, Atari ST, Commodore 64, and others) and Wing Commander: Privateer (1993, PC) are musts for fans of the genre.

Like Echelon, Origin's Space Rogue tried to put its own unique stamp on a genre popularized by Elite, this time by adding significant role-playing elements.

On a more basic level, Atari's Star Raiders from Doug Neubauer, first released in 1979 for Atari 8-bit computers and covered in its own upcoming bonus chapter, set the tone for Elite's overall presentation more than any other game before it.

With its groundbreaking, real-time, simulated 3D space combat, Star Raiders featured smooth graphics scaling, particle explosions, a rotating sector scanner (map) and an optional rear view of the standard first-person perspective action. That Bell and Braben were able to so profoundly expand Neubauer's classic vision is a testament to their ambition.

Elite and its descendants have much to offer fans of science fiction, but also satisfy more basic desires, such as accumulating great wealth or earning a stellar reputation as an intergalactic badass.

However, unlike science fiction universes like Star Trek in which capitalism is downplayed or even nonexistent, space sims make it an indispensable part of the gameplay -- even though Braben stated that Elite "was never intended as a pro-Capitalist game in any way."[5]

Nevertheless, the game's emphasis on accumulating capital and rewards for ruthless, unethical behavior seem to represent anything but a critique of capitalism. In Elite, space is not so much the final frontier as it is the final free enterprise.

Although there are various ways to play Elite, most players end up balancing buying and selling with combat. It's possible to avoid combat by sticking to the well-policed trading routes of stable governments, but much bigger profits lie in exploiting less harmonious civilizations. The manual outlines other possibilities, such as bounty hunting, smuggling, and pirating.

Players are of course free to pursue whatever path they find most fulfilling, and many of the same upgrades that make one successful in one are also helpful in others. For instance, the fuel scoop can be used to save money by allowing players to refuel their ship by flying close to a star, retrieve ore from asteroids, and salvage freight from ships the player has destroyed.

Later derivatives would require players to focus on one activity or the other, inhibiting the more jack-of-all-trades possibilities of Elite.

Shown here is a combat sequence in Elite. The numbered bars on the lower right indicate the strength of the shields. The player can also select rear, left, and right cameras. Additional weapons can be mounted in each of these positions as well.

These later derivatives of Elite would also focus more on fulfilling vital missions or following a preset storyline, but the original is almost entirely focused on combat and economics, in spite of the author's direct inspiration from the pen-and-paper role-playing game (RPG) series from Game Designers' Workshop, Traveller (starting 1977), and popular science fiction authors like Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov.[6]

Perhaps to compensate for the lack of story, the publishers commissioned a novella named The Dark Wheel from noted sci-fi and fantasy author Robert Holdstock. This surprisingly readable novella does an excellent job setting the context for the game, and is highly recommended for anyone interested in Elite.

It is tempting nowadays to disregard such materials and focus entirely on the game itself, yet even such things as a well-designed box had a significant effect on gamers of the time. A game historian -- or really anyone who really appreciates Elite -- should take the time to read the well-written manual and novella in their entirety. Thankfully, both are available for free online.

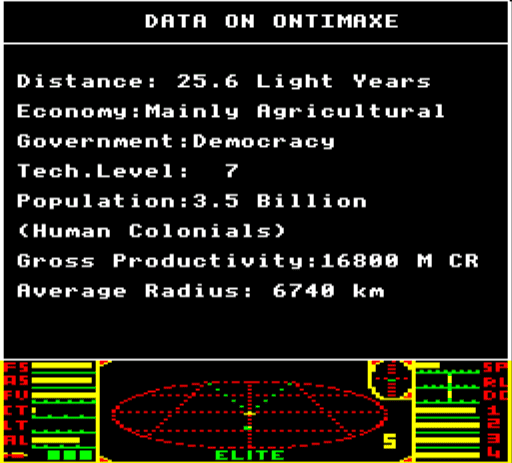

The starting system in Elite has several planets for the player to visit. Although the ship cannot land on planets, it can always dock at the stations in orbit around them.

Elite does have some missions sprinkled about the vast universe. However, these are quite rare, and the details vary from version to version. Bell comments that he wanted the teams making the ports to "do their own thing missionwise and have fun with it."

For instance, one of the more memorable missions from the Commodore 64 version is inspired by the classic Star Trek episode "The Trouble with Tribbles," where tiny, adorable fluff-ball creatures who are Klingon-averse interfere with Captain Kirk and crew's mission to protect a shipment of grain. For the most part, though, players were left to create their own narratives.

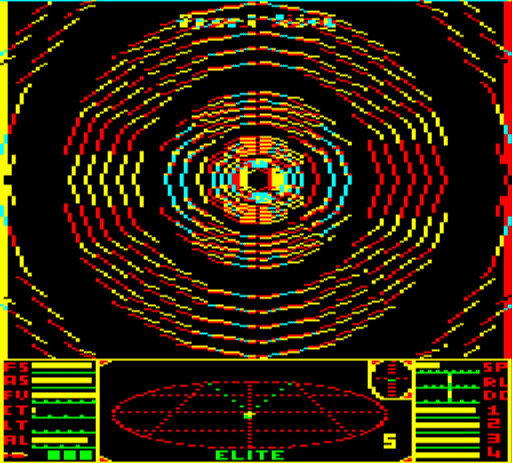

This colorful screen effect represents hyperspace, or faster-than-light travel in Elite.

[5] See http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3470/nextgen_narrative_the_david_.php?page=2.

[6] See http://www.hooplah.com/encounters/trivia.htm and Rusel DeMaria, Johnny L. Wilson, High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games, pages 340-341. 2002, Osborne/McGraw Hill.Berkeley, CA.

Elite puts players in control of a Cobra MK III, a high-quality and highly customizable intergalactic spaceship. Although the Cobra cannot land on planets, it can dock with the space stations that orbit them. Initially, the ship is armed only with the weakest of weapons, the slow-firing pulse laser.

Likewise, the ship is lacking almost all of the exciting options and customizations, such as a larger cargo bay or an automatic docking computer. This last option is particularly valuable, given the complexity of the manual docking procedure -- widely hailed as one of the game's most memorable, if frustrating, aspects.

Obviously, players should begin making money as soon as possible, gradually outfitting the ship to better suit their needs. For instance, instead of saving towards a high-yield, military-grade laser, players could opt for a humbler yet useful mining laser that lets them collect valuable ores from asteroid fields.

Players who frequently engage in battle may want additional lasers for the rear of their ship, whereas those who are more cautious may prefer an escape pod or energy bomb. Players with slower reflexes can opt for homing missiles rather than lasers.

Most players will at some point acquire a fuel scoop, which will let them refuel for free at stars, but more importantly, will scoop up cargo that drifts into space from asteroids or beaten opponents.

There are dozens upon dozens of possible configurations, and many of them make an immediate and noticeable difference to the gameplay. Anyone who loves the game will eventually want to try them all.

Each system in Elite has corresponding data that is important for trade. The type of government is important as well; less orderly systems are more prone to piracy.

Besides the pride of piloting a well-modified ship, Elite offers other means of measuring one's prowess: ranks. The rank is an indicator of a player's overall combat skill. The player will begin with the miserable "poor" rank, move up through several stages including "competent" and "dangerous," and finally join the vaunted "elite," the deadliest pilots in space.

There are also three reputation ranks: clean, offender, and fugitive. Players who consistently break the law will find themselves hunted by the futuristic equivalent of the highway patrol, "galcops," who fly about in packs of vicious Viper-class ships.

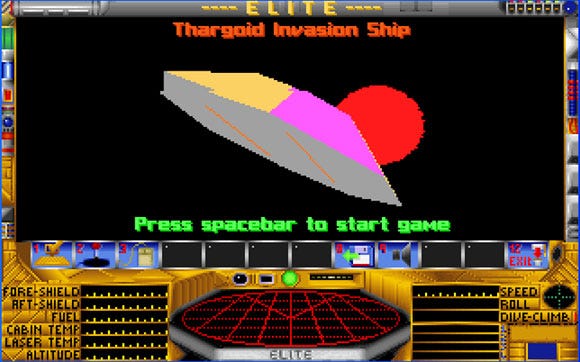

Banditry and marauding may not appeal to everyone, but they are certainly some of the most challenging ways to play the game -- and pirates and police aren't the only threats lurking out in space. The insectoid Thargoid race is at war with humanity and its allies, and only the best pilots can hope to survive an encounter with their invasion ships.

Although these monochrome, wireframe graphics from Elite may look primitive today, the real-time, 3D rendering impressed then-owners of the humble BBC Micro and other 8-bit computers.

The game consists of two basic interfaces: a mostly text-driven menu interface for trading and upgrading, and a first-person, simulator-style view for spaceflight and combat. An intriguing sensor system at the bottom shows other ships and objects in three dimensions.

Objects that are above or below the character are represented by dots connected to lines that resemble narrow towers. The sensors may be confusing at first, but quickly make sense and become useful. Although other aspects of the interface resemble a conventional flight simulator, flying in space is much different than Earth-based flight.

Elite adheres to realistic physics. For instance, the player can roll the ship clockwise or counterclockwise, but can only turn by aiming in a direction and firing the engines. It takes practice and patience to learn to maneuver the ship, and even more to maneuver it well enough to survive combat.

Players can also make special maneuvers based on the gravitational force of planets or bodies. All in all, the game makes high demands on players and has low tolerance for incompetence. Although this level of difficulty may turn away some players at the gate, others savor the challenge.

Exploded view of the packaging for the Commodore 64 version of Elite. Note the red Lenslok antipiracy device, which the player had to hold up to the screen in order to decipher two characters in order to successfully run the program. As an antipiracy device, this proved fairly effective and a target for those who didn't purchase the game. As Author Barton puts it, "My dad and I were searching for this game for weeks, but every time we found them on store shelves, someone had already opened the boxes and stolen the decoders!"

Elite met with good overall commercial success and remains a common item on many "best of" lists, particularly those compiled by British gamers.

The game was widely ported to the popular computer platforms of the era, though there's a surprising European-only console conversion for the Nintendo Entertainment System from 1991, which Bell cites as his favorite.[7]

Collectors and historians should note that some versions of the game incorporated a cumbersome copy protection scheme. During the loading process, a screen of gobbledygook would appear that could only be deciphered by peering at it through a type of decoder device included with the game.

In 1991, Microplay Software released Elite Plus, a VGA-remake of the original game. It was only available for PC DOS machines with the requisite hardware, and reviewers weren't as impressed as they had been with the former title. Stanley Trevena, a reviewer for Computer Gaming World, wrote that "some classics are best left in their original form and not artificially modernized."[8]

Although Elite Plus featured an audiovisual upgrade, not much else was changed.

A full sequel from GameTek, Frontier: Elite II followed in 1993, designed by Braben for the Atari ST, Commodore Amiga, and PC. The sequel improved the graphics, sound, and physics modeling considerably, with the new ability to land on planets, but the box makes the more intriguing claim that "all the planets and moons of our own solar system and others... are generated in accordance with current theories of planet formation."

This emphasis on good science and accurate astronomy is reminiscent of Spacewar!, one of the earliest computer games that also boasted of accurate stellar cartography (which will be covered in an upcoming bonus chapter.) Frontier: Elite II was primarily Braben's project, though Bell contributed programming and consultancy.

Bell is distinctly critical of the game, remarking that "David wants everything to be 'realistic' but that's just not the right way to go."[9] Braben and Bell clashed over more than design issues; Bell felt that Braben wasn't giving him due credit for the Frontier games, which are of course based on the earlier co-developed work. The matter is still outstanding.

Frontier: Elite II met with mixed reviews from critics, some claiming it was the best game they had ever seen, while others found it hopelessly boring. A visually improved but bug-infested sequel, Frontier: First Encounters followed in 1995 for the PC, whose major addition to the series was the inclusion of story-based missions.

A patch fixed most of the worst issues, but the damage had been done. The sad truth was that other developers had long since eclipsed the pioneers of the space sim genre.

Frontier: Elite II added several new features, including the option to buy new ships and land on planets.

Although Elite doesn't seem to have fared well as a franchise, its unique combination of gameplay elements laid the foundations for a new and exciting genre. Although space sims aren't as prevalent today as first-person shooters or online role-playing games, they are still being produced and will no doubt become even more engrossing as audiovisual and world simulation technology continues to improve.

[7] See http://www.iancgbell.clara.net/elite/archive/c2031200.htm.

[8] See the October 1991 issue of Computer Gaming World.

[9] See http://home.clara.net/iancgbell/elite/archive/b5081501.htm.

Correction: A previous version of this article said Bell had no involvement in Elite 2 -- however, he did contribute programming and also consulted on the game. Previously, the article also said Braben and Bell settled their dispute -- this is not the case. We've updated the article to reflect these inaccuracies, and apologize for the error.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like