Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this, the second part of a three-part series, MMO economy expert Simon Ludgate examines the concept of faucets -- how money comes into the game and goes back out again, making some surprising revelations about what's truly crucial to a healthy game economy.

[In this, the second part of a three-part series, MMO economy expert Simon Ludgate examines the concept of faucets -- how money comes into the game and goes back out again, making some surprising revelations about what's truly crucial to a healthy game economy. You can read Part 1: Fairness here.]

In part one of this three part series, I addressed the issue of fairness in MMORPG economies -- specifically in regards to buying and selling equipment on the in-game market (versus locking equipment to bind on pickup). In part two, I want to address another MMORPG F-word: faucets.

Back in part one, Ultima Online creator Richard Garriott was talking about how economies are controlled in single-player games because the developer sets the rate at which players get money.

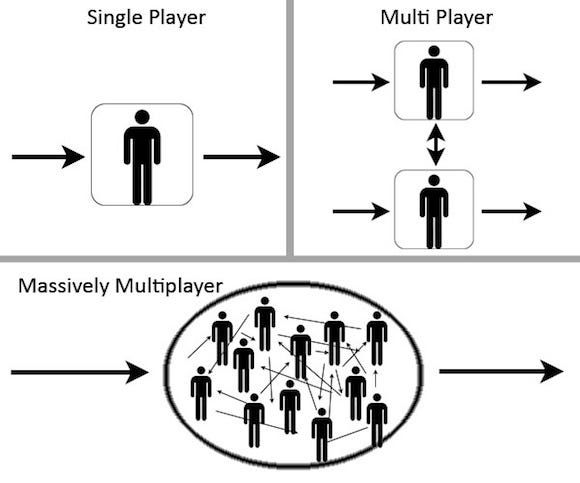

In multiplayer games, this constraint is still mostly maintained, because players choose the other players with whom they play. However, in MMOs, all that goes out the window, because you're playing with everyone else whether you want to or not. The basic economic structures look something like this:

These depict a game's MIMO model: money-in, money-out, the faucets and drains. This flow of money, while fairly simple to govern in single player games, remains a serious and poorly understood issue in MMORPGs. Many developers focus on trying to balance the creation and destruction of currency in their games lest their economies suffer destructive inflation.

"The faucet is the continued injection of 'currency', such as gold being acquired killing monsters or completing quests," explains Lance Stites, when discussing the economy of NCsoft's Aion. "That influx continues and fills the tub, so without the drain, the inflation would be extreme -- creating a world difficult for new players to ever break in to."

The problem with inflation is that "inflation" is a poorly understood term. Trust good ol' Wikipedia to clear it up: "The term 'inflation' originally referred to increases in the amount of money in circulation, and some economists still use the word in this way. However, most economists today use the term 'inflation' to refer to a rise in the price level."

Thus, we need to use two distinct terms:

Increase in price means that the prices of goods have gone up. This means that, if an NPC vendor changes his prices from 300G for a horse to 400G for a horse, or average prices for a stack of potions on the auction house go from 10G to 15G, price inflation has occurred.

Increase in money supply means the amount of money in circulation. If the total amount of gold on your game server was 1000G yesterday and is 1100G today, money supply inflation has occurred.

In the real world, these tend (with a big scary disclaimer on "tend") to go hand-in-hand. When your government stops printing one dollar bills and starts printing one trillion dollar bills to pay for everything it wants, you know your $50k a year salary isn't going to cut it anymore.

That's because in a society with a fixed amount of goods and services, the price of anything is a fixed percentage of the total wealth in that society. If the whole society has 100 loaves of bread, and prints 100 dollars (and you make the rather absurd assumption that loaves of bread are the only good or service) each loaf is worth one dollar. As soon as you print 100 more dollars, each loaf becomes worth 2 dollars, so it's a good deal for the person printing money (he gets 50 loaves now) but it's a bad deal for everyone else, whose one dollar is now worth half a loaf.

However, this isn't true in games, for one big reason:

The "society" in a video game has no fixed amount of goods or services. In the real world, there's only so much land to farm, so much oil to be drilled, so much iron to be mined. Plus, you have property ownership that prevents any random person from acquiring those resources. But in the game world, that doesn't hold true. There's an infinite amount of resources: they just keep respawning as players gather them. So, in a game, whenever you want something, you don't have to buy it... you can go get it yourself instead.

Inflation is a problem in the real world because most people cannot obtain loaves of bread without paying money anywhere (assuming they don't steal). They can't just farm their wheat and craft their tools and, voila, loaves. Because there are limited means of production in the real world, real people have to buy loaves.

In the real world, loaves don't grow on trees or drop from goblins. But in video games, they do. Although I'm stretching this analogy rather thin here, there's an infinite number of "loaves" in a video game and every player has the right to gather them, provided they play the game correctly.

In addition to the infinite resources to gather and craft, video game NPC vendors have infinite supplies of the goods they sell, too. No matter how many times you right-click on the loaf icon to buy it, there'll always be another loaf. And, even better, the prices never change. No matter how many loaves you buy, the prices never go up.

This means that, for every good available in a store, there is a fixed ceiling price for that good. "Ceiling price" is a fancy economics term for saying "the price will never go higher than this." So, no matter what happens in the game's economy, players will always be able to buy that good for at least that price.

Likewise, NPC vendors have an infinite amount of money at their disposal with which to buy junk from players. No matter what it is, as long as the devs flag a set sale price on it, the NPC vendor will buy any number of them. If you have a billion toad leather thongs for sale, the NPC has the cash for them (though I daren't imagine what he does with all of them). This means that, for every good that can be sold to an NPC vendor, there is a fixed floor price for that good. Did you guess that this was a fancy economics term for saying "the price will never go lower than this?" Good on you if you did!

For every good that has both a fixed floor price and a fixed ceiling price, the price of that good when traded between players will always be within that price range. Well... maybe not. No player who actually knows about the economy would pay more than the ceiling price or sell for less than the floor price, but players who are ignorant of those prices might.

Some online games, such as EVE Online, have economies that thrive on preying upon this sort of economic ignorance. Other games, especially those with extremely well-used and comprehensive wikis, help players avoid making these sorts of economic mistakes.

Thus, getting back to Stites' description of faucets, his fear that inflation would make the game difficult for new players is completely unfounded.

Provided that your game is well-designed, that all key goods needed by new players have floor and ceiling prices, all new players will have the same opportunities to earn and spend money no matter how much money is in circulation or how inflated player-market prices are.

Take, for example, World of Warcraft. Players can basically treat WoW as a single-player game, questing on their own, earning money on their own, and spending it at vendors on their own.

Neither the game's money supply nor inflation in the auction house have actual bearing on the experience of a new player who sticks to the game's solo content. However, at some point, that player might click on an auctioneer... and what happens then?

This is where I get to repeat myself. Time = Money. I said it back in Part 1; I'm saying it again now. It's a basic, crucial truth upon which every economic reality is based.

When the player looks at the prices of things on the auction house, the player has to make a choice: buy it at that price on the AH, or go get it yourself. One costs money, the other costs time. If a player is equally willing to spend either resource, then they should do whichever is cheaper: if the player can get the money to buy the thing in less time than getting the thing itself, then they should buy the thing.

Really, this is the basic idea behind real world economies, too. How much time would it take you to make a loaf of bread if you didn't buy (or steal) anything? You'd have to go find unclaimed arable land, which might not actually be possible, but let's assume you can.

Then you need to either find wheat on that land or find wheat seeds and plan them on your land and wait for them to grow. Then you need to harvest that wheat, which might be difficult with your bare hands. Maybe you find some wood and stones and fashion your own tool. Then you have to grind the wheat grains into flour, and also find all the other ingredients, and very quickly you realize you might many weeks to a year to make just one loaf of bread.

However, once you have the process of making bread down to a practiced art, it's easy to make a lot more than just one loaf of bread. In fact, it's easy to make far more loaves of bread than you yourself can eat. At this point, the idea of spending more time making a lot more loaves and trading them makes more sense than making just a few loaves and then spending time doing everything else yourself too.

And, as it happens, the more you specialize in what you do and the more you trade with others, the more efficient production becomes. So if you have one person specialize in making wheat, one person specialize in grinding grain into flour, and one person specialize in baking flour into loaves... well, I'm sure you've seen that three step mechanic in many games already.

And yet, you probably haven't seen it very often in MMORPGs. That's because most activities in most MMORPGs are highly isolated and designed to be extremely self-sufficient. Most of these games haven't just made it viable to do everything yourself; many of them require you to do everything yourself. I can't tell you how many times I remember someone in WoW saying, "Yeah, just a sec, I gotta mail these herbs to my alchemy alt and mail back the elixirs." Everyone did everything; trade with other players was not a route to efficiency.

That's partly because of how these games design their resource-gathering systems. In most MMORPGs, gathering resources is largely a hit-or-miss event where you wander around clicking on nodes or killing monsters for random drops.

Most crucially, the time spent and resources gathered are a linear relation: if one hour will net you 20 herbs, two hours will get you 40. This is a key difference from "real world" harvesting, where the result of your labour goes up dramatically with extra work. Spending one hour a day for one hundred days might net you 10 pounds of flour, but spending eight hours a day for one hundred days might net you 10,000.

The big difference is that, in MMORPGs, spending your time specializing in gathering one type of resource is no more efficient than being a generalist gatherer. In fact, quite the opposite: gathering multiple resources at the same time is far more efficient than harvesting just one type.

And, to really throw a kink in economic principles, you often end up gathering more resources than you initially set out to get. Basically, harvesting in an MMORPG like WoW is like a farmer who keeps picking up ore nuggets, fruit, nuts, live animals, pieces of advanced technology, and magical artefacts and popping them in his sack while he's just trying to harvest his wheat. It's an absurd extreme opposite to the realities that make specialization of labor valuable.

If you're worried about "faucets" flooding your game with cash, maybe you should take a serious look at faucets of other resources too.

What do you think happens when a player gets back to town to sell what they harvested... and all the other junk they picked up along the way? All this other junk is useful to someone else, but it's junk to the person who gathered it. They didn't want to gather it. It just sort of fell into their pockets. So they go to the Auction House, look at the current price of that junk, and undercut that price. Why? It's simple. They just want to get rid of it as fast as possible. It's junk. That's what you do with junk. You get rid of it.

It turns out that the real faucets in many MMORPGs aren't the cash drops: it's everything else. And the result isn't inflationary prices. Quite the opposite: because of all the competition to unload junk on the open market, prices deflate very near to the floor price.

At some point, it's cheaper (and more convenient) to just vendor the junk than to try and sell it to other players. That's a good sign that the market is saturated with that item and it has reached rock bottom prices.

As it happens, currency faucets aren't an issue at all. Besides, such faucets already exist. At any time in most MMORPGs, a player could dedicate themselves to performing activities that generate money, such as killing monsters.

Because players are in control of the money supply, they can already open that faucet all the way and flood the market with currency. The only thing that stops them from doing so is time. At some point, their time is better spent doing something else.

If the market isn't completely deflated, they might be better off spending their time gathering resources. But that's unlikely in most MMORPGs.

The bigger issue is when players would rather spend their time outside of the game. Picture it: someone wants something, but doesn't currently have the money for it and doesn't want to spend the time gathering the money for it. Why? Their time is limited. And when time is limited, it's worth a lot more.

This is where gold farming comes in. Gold farming is the ultimate faucet: you pay someone real money for them to spend their time getting you gold. At least, that's how it works in theory. When it comes to gold farming, there are two basic facts:

Players and game makers alike suffer from gold farmers.

Players and game makers alike don't suffer from gold buyers.

That players suffer from gold farmers is undeniable. The spam alone is horrible in many online games. Gold farmers also try to find exploits they can abuse, many of which disrupt the game for other players. Gold farmers can also have a deeply disruptive effect on the in-game economy if they can get money from other players more easily than from the game world. They also hack into players' accounts, stripping them of everything of worth in order to more quickly fill their coffers with more gold to sell.

Game developers and publishers also suffer from gold farmers. "If you're talking about what different kinds of fraud exist in the world, the ones that for us as a developer and a publisher, the kinds of fraud that concern us the most, are the actual credit card frauds," says Scott Hartsman, executive producer of Rift at Trion Worlds. "Where you go buy gold from a disreputable gold site, and they say 'thank you' and deliver your gold, and sell your credit card number, or start registering accounts with your credit card.

"It's those kinds of things where people laugh and go, 'Oh, that never happens.' No. It happens. It happens a shitload. To the point where, over the last three or four years, I would dare anybody to ask an exec at a gaming company how much they've had to pay in Master Card and Visa fines, because of fraud. It happens a lot. Those fines are money that should be going into making games better, and instead they're going into fighting the fact that people are jerks in the world."

So it's clear that gold farmers are bad. What about gold buyers? Is it bad that they receive big chunks of gold they don't work for? I don't think it's a problem.

"One millionaire blows out the experience for their rewarded character or even their friend's first-level character," says Turbine creative director Cardell Kerr. "I think that's fine in today's game-space, mostly because I want to play with my friends.

"We've got to the point now where, when I log in to a game, whether it's an MMO or an FPS or some odd combination of the two, I want to go over to my friends and hang out with my friends. Because of that fact, because that's the experience that I think is important nowadays, I think that compensating for the money coming in, in terms of the money you're creating on a moment-to-moment basis, is probably tilting at a windmill."

I think there's a very simple comparison: would you think it unfair if someone logged in and their friend handed them a big pile of gold and/or gear? Probably not. Even though it's "unfair" that this person has a friend helping them and you don't. So I don't think the "unfair" argument applies to gold buying either.

So, if gold "receiving" is okay but gold "selling" is bad, what's the solution? It's quite simple: MMO makers should just sell their money. And this, my friends, is where we finally get into the economic nitty-gritty.

Remember, there's already an infinite gold faucet wide open, waiting for players to hold their buckets under it and wait for them to fill. The only difference is cutting out the wait time. What you're doing is just make the faucet flow faster.

This is where people panic. Oh noes! Prices will go up! That's not actually a bad thing, really. Remember that prices are deflated to rock bottom at the moment. There's already way more production of goods from random adventuring than there is demand for those goods, mainly because everyone's out there doing the adventuring gig too. Bringing in some gold buyers would help clean up all the junk those pesky adventurers bring back to town with them.

The real concern is what those players are buying at the Auction House. What is it that will go up in price? Most likely, the items that will really go up a lot in price, the items that give concern about inflation, are the super rare items that are already prohibitively expensive. So prohibitively expensive they prompt people to buy gold from gold farmers to be able to buy them.

See, here's another way in which MMORPGs differ dramatically from real life. In real life, producing a really awesome rare thing is usually the result of a tremendous amount of work and time and creative inspiration. In an MMORPG, it's the result of right-clicking on a sparkle and getting that one-in-a-billion random loot generator result with a purple name.

The thing is, in real life, people can work towards making those things. You can say you'll paint the greatest masterpiece and set yourself to painting until you achieve it. In doing so, you're not likely to produce some other great masterpiece, like accidentally composing a fantastic symphony or discovering the cure for cancer. But in an MMORPG, it's all random. You could stumble across the greatest epic of your life dropped by the seventh rat in a kill-ten-rats quest. And you can't set yourself to trying to get it, even if you did want to take that up as your cause.

The randomness of these goods already makes them extremely volatile in price. Gold farmers frequently snatch them up when they show up on the Auction House and relist them for unattainably high prices; the only way to actually buy them is to buy the gold from the gold farmer. It's a viciously effective cycle for converting what people really want -- the shiny epic, not the gold -- into real money.

The way to fix faucets and drains is to wean developers away from the notion of equipment as a means of progression in MMORPGs. Instead, treat equipment like equipment: something to be used and replaced. Bring back item degradation, item loss. Make items something that players expect to buy on a regular basis. Make them affordable and common.

All of this can be done with improvements to one of the greatest shortcomings in modern MMORPGs: the crafting system.

EVE Online's powerful and stable economy is arguably strong not only because of its economic foundations but because of its crafting system. Everything in EVE is crafted; everything in EVE can be blown up and lost and need to be replaced.

Money flows in EVE because everyone always needs something from someone else. This is a huge difference from the design philosophy of themepark MMORPGs like World of Warcraft, where no one ever needs anything from anyone else because no one can ever get anything from anyone else. In WoW, everything of value is Bind on Pickup: you have to get everything yourself.

On the one hand, making a game's crafting system into one that encourages players to specialize into one role adds a lot of economic motivation to the equation. In EVE, you have miners, haulers, and crafters, each doing their own different thing. On the other hand, it's important to make sure that a game's crafting system remains sufficiently open so that players can compete in each aspect and ensure that no monopolization efforts introduce inefficiencies. EVE has some problems with that; other games, like EverQuest II, fared far worse.

When EQ2 launched, the game had a highly specialized crafting system. There were nine crafts and each finished item made by each crafter required components made by other crafters -- sometimes all eight. However, almost every single step required at least one liquid produced by alchemists, creating massive dependency on alchemists by every other crafter, and making it all too easy for a few alchemists to grind the economy to a halt.

"The game we had launched back in 2004 is obviously very different from what it ended up being in later years," explains Scott Hartsman, when telling me about his experiences with EverQuest II. "A lot of that had to do with us observing how accessible crafting was as a whole, how difficult it was to get started, and -- most importantly -- how much power were we letting small numbers of people focus over an entire server's economy.

"With that level of interdependency, that is a very complicated game to play. For some of these recipes, you would have to craft 40 things -- 40 subcomponents through different tiers -- before you could make the final thing. And when all of those things are dependent on other people, what we ended up with was very small groups of people effectively controlling an economy of an entire server."

I pointed out that one of the biggest problems in when EQ2 launched was the lack of a centralized marketplace system. EQ2 eventually added a broker system, but it required players to stay logged in for things show up. I asked Scott if he thought a market system like EVE's, with buy orders so alchemists could see which people were paying what for liquids and produce to fill those needs, would have made EQ2's interdependency more viable:

"I think it would make a more interdependent system more viable, to be sure. Here's the thing: crafting interdependency and dungeon grouping are analogues to each other in different action spaces. It's not that people don't like other people; it's that people don't like inconvenience. And other people are the most inconvenient thing in the world."

I've always said the worst thing in massively multiplayer games are the other players.

"Yeah! We all say that because it's pithy and funny, but it is true. So crafting interdependency is the same thing. Everyone likes the idea of, 'Oh, this is so deep and there's all kinds of stuff,' but 'Ohhh, wait. Now I've gotta find ways to get this stuff? Oh, this isn't fun.' So yeah, adding more systems like that, I think, are a great way to get more interdependency in a fun way."

So here's your checklist to making a successful MMORPG in-game economy:

a) Make sure there are resources that are needed that everyone can gather, including new players. Follow EVE's "more Tritanium!" model rather than the themepark "highest level mats only" model.

b) Encourage specialization of labor by making systems that reward players for specializing in one thing, be it gathering or crafting, and encourage interdependency by having different specializations require output from other specializations...

c) BUT DON'T make it impossible for players to go out of their specialization in order to correct for market inefficiencies. Most importantly, don't make it impossible for a player to change their specialization at no cost. This means: don't do a "two crafts ONLY!" system like WoW or Rift when you could do an "everyone can work on everything" system like in Final Fantasy XIV or EVE Online.

d) Build systems that make it easy for players to transact without actually having to interact. Markets with buy and sell orders are a great way for a player to indicate their desire to make an economic transaction without having to actually find someone to listen to them first.

e) Worry more about equipment faucets and rains than cash faucets and drains. Don't neglect cash drains, but worry a lot more about equipment drains. Binding doesn't count; eventually everyone will have a bound copy of everything and no one will be able to sell their goods. Get rid of permanent gear. Get rid of gear-based progression!

In the third and final instalment of this series I'm going to go way out of the in-game economy and talk about the real-world economy. The biggest F-Word on everyone's lips, when it comes to MMORPGs, is Free (to play). So I'll be re-introducing some of the ideas I discussed during my presentation at this year's Canadian Games Conference and adding in plenty of additional in-depth insight. Stay tuned!

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like