The evolution of video games as a storytelling medium, and the role of narrative in modern games

This essay aims to investigate the topic of narrative in video games. Specifically, the evolution of narratives in games, and the role of narrative in today’s story-based games. Narrative is all around us; we can interpret all events as stories with plo

1. An Introduction to Narrative

1.1. Defining Narrative

In a paper exploring the field of narrative and its prominence in video games, the logical first step would be to establish a baseline definition of what narrative is. During the past decade or more, many broader interpretations of the word have arisen, stretching the meaning to involve “belief, value, experience, interpretation, or simply content,” [1]. For this essay, a much narrower definition is required, since narrative regarding games (and my approach the subject of narrative in this essay) refers to storytelling, and the relation of events and characters. Therefore, an appropriate definition would be H. Porter Abbott’s, made in 1978, which is “the representation of an event, or a series of events” [2].

This definition encapsulates the most basic interpretation of the word, and is a nice, simple way to describe narrative when it is referenced or alluded to in this essay. However, I feel that expanding upon this definition before continuing may prove beneficial. In her paper Defining Media from the Perspective of Narratology [1], Marie-Laure Ryan gives three features by which narrative can be explained, which can be summarized as follows: A “Story that takes place in a world populated with individual agents and objects”, which “must undergo not fully predictable changes of state”, and these physical events “must be associated with mental states and events (goals, plans, emotions).” These three features form a very clear rule by which to define narrative and what counts as a narrative or not.

1.2. A History of Narrative

Since humans have been communicating, they have been using narrative to tell stories, and it is a topic that has been studied since the time of Aristotle, when he laid the foundation for narrative study in Western culture with his book Poetics [3]. Aristotle theorised tragedy (which was in those days a term used to describe a form of theatre in which tragic events were experienced by the main character), and concluded that plot, or “the arrangement of the incidents” [3] was the most important of the six ingredients of a tragedy. The other ingredients, as he described, were Character, Thought, Diction (the way language is used to convey and represent ideas), Song, or Melody, and Spectacle, given in order of importance. Another concept of narrative defined by Aristotle is that any given story must have a beginning, where a problem is encountered, a middle, in which the characters struggle to overcome the problem, and an end in which the problem is resolved.

Aristotle is widely accepted as the biggest influence on the development of literature in the West, and the thoughts we have about the subject today largely come from his ideas. The ingredients of tragedy that he defined can be seen in modern narrative, and in fact they translate to the definition that we put together before. The individual agents and objects refers to character, the change of state is the plot, and the mental states and events are thought. Stemming from Aristotle’s work, the field of narratology was formed, a study that was most prominent around 1960, which aimed to identify what narratives have in common. The way we tell stories and the way we interpret events has been changed a lot by this research and the work done in this field, because it translates to the narratives that are presented to us in our daily lives.

In the world today, narrative has become such a core part of how we interpret events around us. We see it in every medium from musicals and poems to television and radio, and now we see it in video games as well. Through this exposure to the media, as Helen Fulton describes, “...our sense of reality is increasingly structured by narrative.” [4] We begin to think of everything as a structured story, because we understand that every event that we experience in our lives can be told through a narrative. While the main form of storytelling has always been speech, in the modern age narrative is presented to us most prominently through digital media, especially television and (more recently) video games.

1.3. Narrative in Digital Media

The twentieth century brought about the beginning of the digital age, the age of computers, and television, film and video. Before this, there were significantly less devices through which to tell a story; The main media that conveyed narratives were conversation, books, and plays. But the introduction of film and cinema, which Marie-Laure Ryan describes as the “art of the twentieth century” [5], saw an evolution in how narrative can be told. In her article, Ryan describes how cinema gave new dimensions to novels and theatre. It allows events to be represented as they happen in the present tense, in a similar way to written tales, while also transcending theatre in its visual representation. The ability for film to put its audience in the action through cinematography and music was revolutionary.

Television and the internet make narratives more accessible than ever before, and contributes to the importance that human cognition puts on them. We might see an advert for a cleaning product, where a child spills his or her drink, and a frustrated mother will try in vain to fix the mess with a ‘regular’ cleaning product, and thus turn to the advertised product. Even this example uses a problem and solution narrative to give authenticity to the product, that resonates with audiences because it is relatable. Modern social apps such as Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram give users the opportunity to experience their friends lives and adventures in the form of ‘stories’. Narratives can be experienced now more than ever before, due to the amount of media we consume through the internet and through our devices. Video games are the next step in digital storytelling, ushering in a new concept of interactive narrative.

2. Narrative in Games

2.1. A Brief History of Video Games

It is strange, perhaps even incredible to consider how quickly video games have developed from when they began in the 1960’s, as we move towards an ever increasingly technologically dependant world. In his book ‘The Singularity Is Near’ [6], Ray Kurzweil compares it to biological evolution, drawing conclusions that over time, advancements become more rapid, as we use tools from previous generations to progress to the next. This has allowed video games to advance at a very high rate. As we step into the world of video games to discover the evolution and the role of narrative in them, we must take a moment to explore the evolution of video games and look at the history of the medium.

As detailed in The Complete History of Video Games [7], the first interactive video game was created in 1962 by MIT student Steve Russell. It was a space combat game aptly called Spacewar [20], where two player-controlled spaceships fought against each other around the gravity well of a star. This was the most basic of games by today’s standards, but it was revolutionary at the time, and paved the way for a lot of development in the field of computer science and programming. Though this game was developed openly by community members over the following years, it wasn’t until almost a decade later in 1971, that it became the first arcade machine (released as Computer Space [21] by Nutting Associates). A year later Atari was formed by Nolan Bushnell, who headed the development of Computer Space, and Pong [22] was created by Atari engineer Al Alcorn.

The first home videogame system was the Odyssey, created by Magnavox in 1972, which could be plugged into a television, and came with several games including Tennis [23] and Ski [24]. Three years later, Atari created a Pong unit for home use as well. In 1977, a series of LED-based handheld games were released by Mattel. From this point, the development of the industry speeds up rapidly, with the main companies like Nintendo, Atari, Sega, Namco, and others start developing games and systems at a higher rate. During this time arcades were doing extremely well, with Pacman [25] being released in 1980, which would go on to sell 300,000 units worldwide. 1986 saw the release of the Nintendo NES, the Sega Master System, and the Atari 7800, which were all very successful. During the 90s, PC gaming started to become prominent with games like Doom [26], and new consoles were introduced, including Sony’s PlayStation and the Nintendo 64. The late 90s brought a new trend in handheld games with popular titles like Pokémon [27]. From here, the games industry would only become more successful, and would develop into what we see today.

2.2. Narrative in Video Games

In this section, I will begin to explore the first part of the essay title, which is the evolution of narrative in games. I will begin by looking at the different styles of narrative that are usually found in games, and describing each of them in turn. Then, using specific examples, I will explore two games from the 1980s and 90s, and look at their stories and the way in which they show them. Then using the same method, I will investigate two more modern games from this decade. After these discussions, conclusions should be made by comparison about the evolution of narrative in video games.

Here it may also be necessary to mention that not all games have, or focus on narrative. For example, sandbox games, simulation games, sports games and the like have no need for a story or even context behind them. Minecraft [28], as a specific example, provides no semblance of story, no reason as to why the player is there in the world, nor a plot to guide them through their experience. Instead the player is free to create their own story in the world, relying solely on their own imagination to create some form of plot, rather than any interaction with the game itself. Since the most important element of narrative is missing, it cannot be said that Minecraft has a narrative. These games are not the type this essay will be focusing on. For the rest of the paper, the games we look at will be ones that have an obvious narrative attached to them, or that are completely story-based.

2.2.1. Types of Narratives

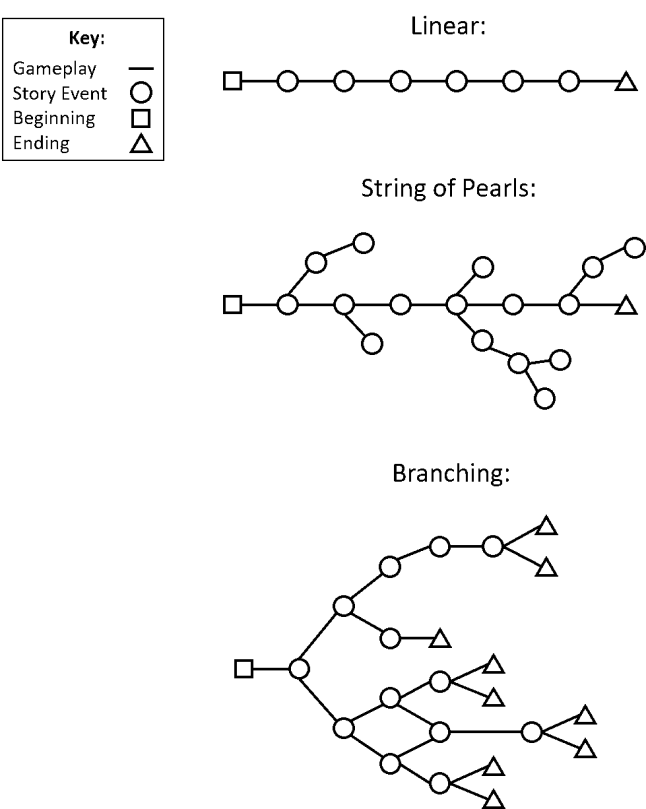

The first thing to note about narrative in games is that there it two parts: the structure, referring to the progression of the story, the different sections and subsections, and how they are connected and interconnected to form a plot, and the portrayal: how the game conveys or shows the story. There are three main types of narrative structures that are usually found in games, the first being linear. This is likely a familiar concept, as it is the structure found in other mediums such as literature and film, since these mediums can almost only use this model. The Google definition of linear is ‘progressing from one stage to another in a single series of steps’, and this is essentially the case. In a linear narrative, the story progresses from one event to another in a single straight line, with no deviation, backtracking, or skipping ahead. In games, linear narrative offers players no interaction with the story. They are not given choices that affect the story, and cannot alter it through gameplay, therefore being unable to dictate how the story plays out. The game can only be completed one way: the way that was written by the game designers.

The second type of narrative structure is referred to in game design as the string of pearls model. This is where the story is told in a linear fashion, but can be interrupted by player freedom at times. This is a structure unique to video games, as the interactivity required for the player freedom cannot be found in other mediums. This is typically seen in role-playing games, where the main story is linear - made up of separate sequences in the form of missions or quests. The player is given freedom through exploration and side quests that are given throughout the world. The third narrative structure is a fully branching story, where player choice plays a major role in how the plot and characters in the world develop, and how the game ends. This type of narrative has been attempted before video games, in the form of interactive books: this type of novel gives the reader choices at the end of each chapter, each choice sending the reader to a different chapter, giving them a chance to create their own story. This structure is usually used in fully story-based games.

There is a fourth model known as the amusement park model, which is very like the branching narrative except players access story by exploration rather than by completing missions. For example, a story branch will unlock by finding the NPC that triggers it, rather than unlocking it through previously completed content. This is a common structure for open world games. These different structures can be represented well through graphs, using nodes to represent story elements/sequences, and the connecting lines to show gameplay paths. A node with multiple children represents a choice, where each child is an option. Below are the three narrative structures as graphs:

There are also several different ways that narrative can be shown and conveyed to the player in a game. The first is through cutscenes, which is an exposition of the story in the form of a short cinematic. Cutscenes can combine dialogue and action in a way that keeps the player in action, and are used to convey plot development in games the same way film does. Text is a very traditional way to convey plot. A block of text used at each story event is the primary way a lot of older games give context to the player. Dialogue is another way that players can uncover story elements. Talking to NPCs in the game world can uncover plotlines and context for characters and events, as well as giving quests in games that use the amusement park model. The other, and perhaps the most interesting form of storytelling in games is storytelling through the environment and the game world. Letting the player interpret the story through objects, places, and people in the game world allows them to form their own ideas about the plot. This is the rarest form of storytelling in games, however it is prominent and successful in the game Dark Souls [29] and its subsequent titles. Most games use a combination of these narrative techniques to convey story elements to the player.

2.2.2. Narrative in Early Games

Nintendo’s Donkey Kong [30], is widely considered the first game that had a story that players could see unfold on the screen. It was released in 1981, and directed by Shigeru Miyamoto, who had a very different idea about communicating with the player than the rest of the industry did at that time. According to an article about the history of Donkey Kong, ‘Miyamoto wanted to make sure the whole story, simple though it was, could be told on screen in a way that could be instantly grasped by players’ [8]. Donkey Kong is a 2D platformer, where the player character (an early rendition of Mario) must track down his pet ape who has escaped with the player’s girlfriend. The game uses cutscenes at the beginning of the game showing the ape escaping, and every time the player completes the level, upon which Donkey Kong grabs the girl and climbs to a higher level. Small animations and text serve to convey plot, such as the ‘help’ speech bubble that represents the damsel calling for aid.

Crash Bandicoot [31], released in 1996 by Sony Computer Entertainment, is a 3D platformer following the story of a marsupial as he attempts to rescue his girlfriend from the clutches of the antagonist Dr Neo Cortex. In this game, as with a lot of old-school titles, the story takes a backseat to the gameplay. It instead focuses on the platforming mechanics and level design, in order to make a fun experience for the user. In fact, there are only two expositions of plot: the opening cutscene, where Crash escapes from the Cortex’s castle, and the ending cutscene where Crash saves his girlfriend after the final boss fight with Cortex. The plot simply exists to give context to the player’s actions and to give the player a reason to continue playing through the game.

What we can see from these games, is that they both employ a classic damsel and destress story. Both the nameless carpenter and Crash are out to rescue their significant other from the antagonist. In both games, the story also takes a secondary role to the gameplay, existing for the sole reason of giving context to the gameplay. The plot serves as motivation for the player, giving them a goal to achieve that makes them want to progress. They are also both linear stories, and that is an indirect result of the gameplay being linear. In both games, the player completes a series of levels sequentially, with no branching options for gameplay, and in turn, no player choices that lead to branching narrative.

2.2.3. Narrative in Today’s Games

Skyrim [32], Bethesda Softworks’ fifth instalment of the Elder Scrolls series, is well known in the gaming community, and was met with critical acclaim upon its release in 2011. It tells the story of the Dragonborn, a human with the blood and soul of a dragon. The player controls this Dragonborn, moving through the world of Skyrim to discover locations, people, quests, and ultimately defeat the evil dragon Alduin. The game employs a combination of the string of pearls and amusement park models. The main questline is linear, with player emergency not affecting the outcome of the story. However, the player can explore the world, and take part in other questlines. In all of these optional questlines, the player must make choices that affects the characters and the following quests they can take in regard to that questline. The open world nature of the game, and its non-linear gameplay allow this narrative structure to work.

Life is Strange [33] is another critically acclaimed title, part of a new trend of episodic games, where content is released periodically in ‘chapters’. Developed by Dotnod Entertainment, it completely revolves around player choice by employing a full branching narrative, where the player’s decisions affect the outcome of the game and produce different endings. The player watches the action unfold before them from the perspective of the main character Max Caulfield, who discovers her ability to rewind time. The player makes choices through multiple choice actions and dialogue, and all these choices affect characters and events in the future. Unlike any of the previous games mentioned, this one is completely story-based, meaning that the gameplay has taken a backseat to the narrative. This is the type of game that tries to tell a story, where the developers have designed the game to give the player a narrative experience that cannot exist in other mediums such as literature or film.

We can see that these two games are drastically different from the old-school games in the structure of their narrative. These games both use narrative structures that allow player interaction and player choices to have an impact on the outcome of the story. Story in these games is used as a foundation for the game world. It does not feel like a component that is tacked on to the rest of the game, but is instead the backbone of the entire structure of the game.

2.3. The Evolution of Narrative

By comparing the games from 20-30 years ago, to the games from the current decade, we can look to draw conclusions about the evolution of narrative in video games. First, the structure of progression: we see that while both early games used a linear structure, the last two employ more branching narratives. Players are not able to interact with the story in early games; no matter how they play the game it will always be the same, because they are not given choices to make that will impact the flow of the game, or how the story plays out. Modern games encourage player interaction, by giving them choices that have real consequences, and allowing them to make their own story by the decisions they make.

The role of the narrative has also changed. In the early games, the story existed to provide context to the game, to give players a goal to achieve and a reason to play. It was almost tacked on to some games, and it would not have mattered if these stories had been completely different, or there at all from a gameplay perspective. Nowadays, developers make games with a story in mind, and the gameplay and the narrative become of equal importance in the game. In a blog post about the development of narrative, specifically in the developer Naughty Dog’s games [9], Chris Bowring writes that “In Uncharted the story was merely there to logically funnel you from one segment of gameplay to the next. However, in The Last of Us, the story and gameplay is one cohesive whole.” Bowring also describes how with games like The Last of Us [34], it shows the game industry maturing with its audience. In the early stages of the medium, games were considered toys for children, but now those who played games as a kid are grown up, and the industry is growing with them. The graphic content and the concepts the game explores attest to this.

The fact that games themselves are becoming more advanced and complex, both technologically and gameplay wise, allows game narratives to evolve in the same way. Early games were very restricted by computing power, to small 2D games that could not support the complexity that is needed for such narratives to exist. Modern open world games allow the amusement park model to exist, and the budgets of today’s games allow developers to invest in complex and detailed narratives, and worlds and gameplay that fully support this. Another factor is that the amount of indie games being produced has skyrocketed in recent years, giving way to more experimental games that are not afraid to try new storytelling techniques.

What it ultimately comes down to is the concept of embedded narratives vs emergent narratives. Older games typically have embedded narratives, which means “pre-generated narrative content that exists prior to a player’s interaction with the game” [10]. They have backstories, and “are often used to provide the fictional background for the game, motivation for actions in the game, and development of story arc.” This is what we see in Crash Bandicoot and Donkey Kong, whereas Skyrim and Life is Strange employ emergent narratives, which “arises from the player’s interaction with the game world, designed levels, [and] rule structure.” “Moment by moment play in the game creates this emergent narrative… depending on [the] user’s actions.” In conclusion, narrative in video games have evolved over time to become more complex and cohesive with the gameplay, moving from embedded to emergent. We have gone from stories being used to show games, to games being used to tell stories.

3. Exploring Modern Narrative Games

This section of the paper aims to investigate the second part of the essay title: the role of narrative in modern games, by building upon what has already been covered in terms of narrative evolution. To begin, we will look at the latest trends in story-based games, and how interactivity impacts storytelling. Interactivity in games will be discussed, particularly how it can elicit emotion from the player and provide new narrative experiences with new structures and ways that it can be delivered to the player. Finally, I will look at the popularity of modern story-based games and the reasons it appeals to people. Using these points, conclusions can be made about the role of narrative in modern games.

3.1. Interactive stories

Until Dawn [35], developed by Supermassive Games and released in August of 2015 for the PlayStation 4, ushered in a new age of video games. Until Dawn is a survival horror game, following a group of eight teenagers as they spend the weekend in a ski lodge. They are there to party, but soon realize that they are not the only people on the mountain, and are terrorized throughout the game by a group of cannibals possessed by evil spirits. The player interacts with the game mainly through quick time events, and decisions that are made by pressing one button or another. There are moments when they player can take control of the characters, but it mostly results in what is referred to as a ‘walking simulator’, where the player simply moves the character from one location to the next. The main mechanic in this game is the use of the ‘butterfly effect’, the notion that even the smallest of choices can have massive impacts on future events. Like Life is Strange, this results in is what can only be described as an interactive movie.

In fact, Until Dawn was a collaboration between Hollywood and the game industry. The two lead writers, Larry Fessenden and Graham Reznick are both well-established figures in the realm of film, having each written multiple Hollywood films. The script spanned more than 10,000 pages, having to account for all narrative branches, all eight characters and the choices that the player makes. Reznick says that “what’s exciting about games, and specifically narrative-based games, is that you can take that approach from filmmaking, the curated narrative, and then explode it out so that the designers and writers of the game are curating a narrative environment for the player, but the player becomes a complicit collaborator” [11]. From this quote by the writer, we can see that he recognizes that Until Dawn is essentially an interactive movie, approached the same way as a film, the difference being that games allow every possibility of that story to be put into the final product.

Telltale Games have taken this concept, and built a franchise upon it. Founded from the remnants of LucasArts, the studio began to develop entirely story-based games, but they developed games in the same way that television does due to the nature of their games. Thus, Telltale created a new format of games. Episodic releases have been embraced by more and more games since the inception of it, such as Hitman [36] and as mentioned before, Life is Strange. These new trends in narrative games mark a branch from gaming; whether they can still be considered video games is a debate that has been raging online for the past several years. This is an important discussion, but not one that this essay will go into detail about. For this sake of this paper, Telltale Games products will be recognized as video games. Despite this, there is no denying that they are a different breed of game entirely. Interactive games have proven extremely popular, as will be discussed further on, and contribute to pushing storytelling in games and storytelling in general further.

3.2. Interactivity and Storytelling

In order to play a game, the player must interact with it, through a human device interface (HID), typically a controller or a mouse and keyboard. Gameplay can only work through player interaction, based on a set of rules provided by the game. However, interactivity impacts not just gameplay, but how the game narrative works and how it tells its story. Craig Lindley explains that “one must learn and then perform a gameplay gestalt in order to progress through the events of the game. To experience the game as a narrative also requires the creation of a narrative gestalt unifying the game experiences into a coherent narrative structure” [12]. From this we can see that for a narrative to exist in a game, there must be a way for the player to interact with it. So the question becomes, how does interactivity impact storytelling in video games?

An obvious answer, one repeated time and time again, is that by interacting with the characters in the game, the player becomes part of the narrative. In games, players control the pacing of the gameplay, and the movements and actions of the main character, effectively becoming a co-author of the story. The interactivity allows stories to be told from the perspective of the player, rather than that of the main character. An experiment conducted by the Department of Journalism and Communication Research at Hanover University sought to understand players’ identification with video game characters [13]. They got half of their participants to play a game for a period of time, while the other half watched. What they found from participant questionnaires is that “people playing the game and thus having the possibility to act efficiently within the character role identify with the game protagonist to a much larger extent than people do who could not interact with the game.” On top of this, the researchers concluded that “the interactive use of the combat game ‘Battlefield 2’ thus allowed for more intense, ‘authentic’ vicarious or simulated experiences of ‘being’ a soldier in a modern combat scenario”.

From this research, we can see that games allow players to identify more with the player character because of the interaction with the game. While in movies you can only watch the characters move around the world, games give the player agency, the ability to pilot these characters themselves. In the beginning of The Last of Us, the player takes the role of a young girl at the start of the zombie outbreak. After about 10 minutes of gameplay, the girl is killed. This is shown in a cinematic cut scene, so it is delivered in the same way as a movie, eliciting the same emotions as the scene would in a film. However, by having played as the girl prior to this, they are able to identify more with her and relate to her, making it harder to see her die. By interacting with the game and taking the role of a character the player becomes attached to that role, and so games can, in some ways, more emotion than other mediums.

The fact that games are inherently an interactive medium opens up a world of possibilities for narrative, and supports a plethora of new storytelling structures and ways in which they are conveyed. A game that must be mentioned, as a specific case study, is Bloodborne [37], From Software’s PlayStation 4 exclusive, released in 2015. In the same realm as Dark Souls, this game uses environmental storytelling, a method exclusive to video games and interactive environments. In the game the player is a hunter, tasked with clearing the city of Yharnam of its people who have turned into beasts. What starts as a gothic horror quickly turns into a cosmic horror, as concepts akin to H.P. Lovecraft’s work arise concerning celestial beings called great ones, and nightmare planes of existence.

On the surface level, and what a player may notice on their first play through of the game, is that there does not appear to be a clear story. There are vague cut scenes that offer unclear exposition, which by themselves make no sense to the player. Players are given clues about where to go in the world to progress, but no clear reason why. There are three endings to the game, one which allows you to allows you to be executed by your mentor, after which you wake up in the city in the morning. Another ending allows you to fight your mentor and take his place, and the third ending sees the player become a great one themselves by defeating the celestial entity called the Moon Presence. At first glance, there is no clear meaning for each of these endings, as there doesn’t seem to be context behind any of them.

But this is the intention, and indeed the beauty of the storytelling used in this game. There is a story to the world of Bloodborne, a complex narrative that involves history and backstory, branching questlines with player choices that impact the outcome, deep lore concerning the characters and locations in the world. There is a reason for everything in Bloodborne, but the player has to find it themselves. The game does not walk the player through the story in the way other games do. No piece of dialogue or cut scene will ever show the whole story, or explain exactly the situation. But these cut scenes and dialogue, along with items found throughout the game world, are clues, small pieces of a puzzle that must be discovered and put together to reveal the whole picture. There are hundreds of items in the game, ranging from weapons and armour to spells and potions. Each item has a unique description, which serves to uncover a part of the lore. Everything in the world is put there for a reason. A seemingly random item found on a dead body can reveal a clue. Only by interacting with the environment, the characters, and the items in the world, can the player seek to understand the story of Bloodborne.

This form of storytelling is something that cannot be found in another medium. Bloodborne puts an emphasis on the gameplay by not forcing the narrative on players, allowing them to skip the story completely if they so choose. But if looked into closely enough, it can be seen that everything about the gameplay and the game world is there to support a convoluted narrative whose complexity rivals those of modern story-based games. It merges ludology with narratology in way that is seldom seen in other games. The fact that the player has a choice in experiencing the story or not, that if they want to know about the world and events and the context of the game they have to interact with the world and interpret those clues for themselves speaks volumes about the storytelling capability of video games. The game makes players feel smart if they manage to uncover the plot, and rewards them for their dedication to, and interaction with the story by providing them knowledge of the game and context for their actions. By looking at Bloodborne we can see that games can tell stories in different ways, made possible by the inherent interactivity that is required to play.

3.3. Why Game Narrative Appeals

From the previous section, we see that interactivity can provide new narrative experiences within gameplay. Modern games keep pushing strong stories that have real messages to show and a reason to show it. We could ask the question, then, have games become a better storytelling medium than film, television and books. But how would that question be answered? How would one compare one medium to another, or quantify each medium based on its ability to tell a story? Each, of course, have their own strengths and weaknesses, but discussing other mediums is not relevant to this paper. Instead, it may be better to ask why some people choose to play story-based games in order to experience narrative. What about the medium appeals to those hungry for story?

It has to be said that story-based games are a relatively new concept in games, and though they are clearly on the rise, at the moment are far from being the most popular type of game. In a breakdown of 2016 video game sales in the US by Statista [14], story-based or anything similar was not recognized as a top-8 genre, instead being classed under ‘other’. Despite this, these types of games have some of the highest user ratings on Steam, with Undertale [38], Life is Strange, and The Walking Dead [39] all scoring above a 95% positive rating, and all ranking within the top 50 for positive reviews on Steam [15]. So while not extremely popular at the moment, they do have an overwhelmingly positive reception by players.

As the investigations in the previous section prove, games are able to give players narrative experiences seldom found in other mediums. A reason that players may choose to play story-based games is because they want to try other narrative forms, such as a branching structure where their choices can make an impact on the game, and where they feel like they can dictate the story. Perhaps people feel like they cannot relate to the stories from other mediums as well as they can with games. They may be too impatient to read books, or sit through a two-hour movie. It may also be to do with the type of stories being told in games, which are generally aimed at a younger generation. People of this generation may feel that the stories being told are more relatable for them.

A paper from the University of Amsterdam [16] detailing the appeal of interactive storytelling suggests that games takes concepts from other mediums and enhances the user’s experience of them. One such concept is curiosity. “When curiosity occurs, users first perceive a state of uncertainty, which comes along with increased physiological activation.” In games, the user does not just think about what will happen next, but “What will happen if I decide this way?” When playing games, “users may combine different mechanisms of curiosity, which should result in a high frequency and intensity of curiosity-based affective dynamics”. What this says, is that when playing games, there are more ways for players to experience curiosity. Other concepts that the paper discusses in much the same way are suspense, aesthetics, self-enhancement (or a sense of achievement for completing the game or solving the story), and task engagement, otherwise known as flow. This links back to games enhancing the emotion of players due to interaction. Overall, the interaction that players have with the game and its narrative is why people may prefer this medium over others.

3.4. Role of Narrative in Modern Games

To conclude this chapter, we look at the overall picture, and look briefly to answer the topic question: what is the role of narrative in modern story-based games? Perhaps the answer is as simple as ‘to tell stories’. Is this not the reason narratives exist in the first place: to communicate events and characters? But narrative is different in video games than it is in other mediums. If books, movies, television, and music seek to tell the stories of the artists behind them, then modern games tell the user’s story. They give the player choices, and a populated environment in which these choices make a difference, and give them control of where those choices take them. Games are being developed to tell stories, and to make the player feel emotions, and think about real-world issues, and so this is the role that narratives take in video games.

4. The Future of Narrative Games

4.1. What the future may hold

Throughout this paper, games narrative has been discussed thoroughly. We have looked at storytelling in early games, and in modern games, and now, we look forward. To think about the future of story-based games is an interesting topic. It is the same as looking at the future of any form of technology, in the sense that we can never really predict what may happen. The future may hold ideas and concepts that nobody has though of at this time, that may seem impossible now. Who, hundreds of years ago, could fathom the internet? We can speculate though, and we can make educated guesses into what the near future may hold for game narrative. The people most educated on the matter are the game writers themselves. Those who have been in the industry for a long time, seen the developments of the medium, and contributed their own work to the industry. B looking at current trends and asking the professionals, we can seek to answer the question of what the future may hold.

Phil Spencer is the head of Xbox at Microsoft, and in an interview with The Guardian [14] he explained the current situation and the future of the Xbox, particularly about what they could offer that would attract more people to the Xbox brand. Among other things, he talked about subscription games, referencing Telltale Games and their brand of episodic games. He also mentioned how the subscription model of television promotes storytelling. “[Subscription services] might spur new story-based games coming to market because there’s a new business model to help support their monetization.” Streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime allow so much content to be produced and consumed, and offers a platform on which users can access all this content by paying a subscription. Applying the same structure to a game streaming service would allow the same to happen with storytelling in games. More content could be produced and consumed, allowing more stories to be told and experienced very easily. A new business model such as this might improve the future of narrative for games.

At a fan event in San Francisco in 2015, Some of the biggest and well-distinguished video game writers were interviewed about narrative in games, and in particular, what they think the future of video game narratives may entail. When asked where games and storytelling are going, Jenova Chen, creative director at Thatgamecompany, talked about story streaming. “Maybe in future games, everybody will have different versions of a story, and someone will have a really amazing version that we’ll all want to watch. That might come from dreams” [15]. This is an interesting concept, exploring the move from current branching narratives where players go from one pre-written chunk of story to the next, to narratives where players create even their own chunks, with no need for written scripts. Perhaps procedurally generated narratives could be the future of storytelling.

Chen also mentions even more interactivity between player and game. “Video games [are] still in the era of silent film. The equivalent of sound and words is the ability of AI to understand what we’re saying. Imagine you’re playing a game and not just pressing buttons, but actually talking to the game.” He went on to describe how much more emotional the interaction could be in a video game if you were able to make conversation yourself. From this we can gather that narrative-based games will almost definitely move towards a place where the player can truly interact with the game, rather than using a designed interface to communicate with the world and its characters. It is interesting to think about talking to an Artificial Intelligence (AI) system inside of a game. If, in Life is Strange, instead of controlling Max and making decisions based on multiple choice, you as the player are Max, and you can make any decision you wanted when faced with a choice. The future of story games will seek to be more interactive, and look to break down the biggest barriers between the player and the game: the screen, and interface.

4.2. Future Technology and Narrative

On the topic of breaking down the screen and the interface, the future of narrative in games will certainly involve Virtual Reality (VR). VR, to give a simple definition, is a simulation of events that users can experience as if they were in the fictional world themselves, through headsets with two screens (one for each eye) and a stereo for sound. It is a very new medium, and is, like games were in the early stages, very restricted by technology. If a game or simulation in VR does not run at a certain frame rate, users can experience severe nausea, and most home computers do not have the processing power to support big, complex games in VR. This means that at the moment, VR games are restricted in terms of graphics and complexity. The large sum of money required to purchase an Oculus Rift or an HTC Vive means that it is not yet viable as a product for the general consumer. However, the medium open up a lot of possibilities for education, medicine, and of course, storytelling.

In an attempt to research storytelling in VR, Disney Imagineering developed a high-fidelity virtual reality attraction based on the film Aladdin, where guests are able to pilot a flying carpet through a virtual environment. Their findings are detailed in a paper [16] that I will presently discuss. Through their efforts to create a simulation that could tell a story, the team found that VR was a much different medium, and there were a lot of challenges when designing the narrative experience. The fact that the camera is fully controlled by the player means that scenes have to be designed around this. Pacing a story can be difficult, because, like in video games, the player controls the pace of the gameplay. Sound is also tricky because it is typically used to carry emotional tone for a scene, however the developers no longer control the timing. Despite these difficulties though, they managed to produce an experience that captured the imaginations of those who tested it. They concluded the research with a few main points, two of which were that “the illusion is compelling enough that most guests accept being in a synthetically generated environment and focus on the environment, not the technology.” And that “VR appeals to everyone. Both genders and all ages had similar responses to [the] attraction.”

What we can learn from this experiment with VR, is that there is no doubt that it will become a standard medium of storytelling in the future. It has the ability to transport the player into another realm of existence entirely; a world to themselves, the ultimate form of escapism. This is the first step towards the future that Jenova Chen describes, and as VR keeps developing and improves as technology evolves it will become increasingly immersive for players. It will allow them to tell their own stories and take control of the narrative. This is certainly the future of storytelling in games.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have sought to understand the evolution of games as a storytelling medium, as well as the role of narrative in modern games, and how it may change in the future. By looking at the narrative structures of old-school games from 20-30 years ago, and comparing them to the narratives of modern games, it can be recognized that games have gone from using a linear structure with embedded narrative, to branching structures with emergent narratives. Games now allow players to take control of the narrative, by giving them choices with meaningful consequences that affect the outcome of the story. Storytelling has matured, going from meaningless damsel in distress cases that serve to motivate the player, to being at the forefront of the game with real messages and important stories to tell.

We see modern trends in story-based games, where gameplay takes a backseat to branching narratives, as in Telltale games and Until Dawn. We find that interactivity enhances the ability for games to tell stories. From research about player character identification it can be seen how even in a linear narrative such as in The Last of Us, interaction with the game and character can elicit more emotions than other mediums, leaving a bigger impact on the player. And the cast study of Bloodborne shows the potential games have for different kinds of storytelling, and how they can be effective and rewarding for the audience. For these reasons, we see an increase in storytelling games, and that these games are being met with critical success. Being able to interact with a game is a strong argument for video games being a viable storytelling medium.

We have also looked in to the future of storytelling in games. We see that story-based games may become even more popular, as new business models provide platforms for content similar to TV streaming websites like Netflix. With VR, and a host of other experimental technologies on the rise, narratives in games are looking to become more immersive and interactive, giving the player full control by putting them into the game.

Could Aristotle, when creating the rules of narrative, have ever envisioned what would become of his work. That his theories and his work would be the foundation of mediums of storytelling that would not exist for thousands of years. Video games as a medium for storytelling have evolved so significantly in the last 30 years, that even those who incepted video games could not possibly have known how far we have come. And we, educated as we are in the field, cannot possibly imagine how far we have to go.

Bibliography

References

[1] M. Ryan, "Defining Media from the Perspective of Narratology".

[2] H. Porter Abbott, The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative, 1st ed. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

[3] Aristotle (350 B.C.E) Poetics [Online]. Available: http://classics.mit.edu//Aristotle/poetics.html [March 29, 2017]

[4] H. Fulton, R. Huisman, J. Murphet and A. Dunn, Narrative and Media, 1st ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

[5] M. Ryan, "Beyond Myth and Metaphor", Game Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2001.

[6] R. Kurzweil, The Singularity Is Near, 1st ed. Penguin Books, 2006.

[7] S. Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games, 1st ed. Roseville: Three Rivers Press, 2001.

[8] T. Fahs, "The Secret History of Donkey Kong", Gamasutra, 2017.

[9] C. Bowring, "How Narrative Has Evolved in Video Games – A History of Naughty Dog", WordPress, 2017..

[10] "Narrative in Games", University of Amsterdam, 2010. Available: http://www.few.vu.nl/~vbr240/onderwijs/pim/Narrative%20in%20Games.pdf

[11] Graham Reznick, August 25, 2015. Available: https://venturebeat.com/2015/08/25/in-sonys-until-dawn-interactive-horror-game-the-players-become-part-of-the-narrative/view-all/

[12] C. Lindley, "The Gameplay Gestalt, Narrative, and Interactive Storytelling", 2002.

[13] Department of Journalism and Communication Research, "Identification with the Player Character as Determinant of Video Game Enjoyment", Hanover, 2007.

[14] "U.S. most popular video game genres 2016 | Statista", Statista, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/189592/breakdown-of-us-video-game-sales-2009-by-genre/. [Accessed: 16- Jun- 2017].

[15] "Game Ratings", Steam Database, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://steamdb.info/stats/gameratings/. [Accessed: 16- Jun- 2017].

[16] C. Roth, P. Vorderer and C. Kimmt, "The Motivational Appeal of Interactive Storytelling", 2009.

[17] P. Spencer, April 28, 2017. Available: https://www.engadget.com/2017/04/28/xbox-one-phil-spencer-subscription-gaming/.

[18] J. Chen, San Francisco, December 5, 2015. Available: https://venturebeat.com/2015/ 12/23/the-masters- of-storytelling-predict-the -future-of-narrative-gaming/view-all/.

[19] Disney Imagineering, "Disney's Aladdin: First Steps Toward Storytelling in Virtual Reality", Virginia, 2017.

Games

[20] Spacewar. [PDP-1]. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1962.

[21] Computer Space. [Arcade]. Nutting Associates, 1971.

[22] Pong. [Arcade]. Atari, 1972.

[23] Tennis. [Odyssey]. Magnavox, 1972.

[24] Ski. [Odyssey]. Magnavox, 1972.

[25] PacMan. [Arcade]. Namco, Atari, 1980.

[26] Doom. [MS-DOS]. GT Interactive, 1993.

[27] Pokémon. [Game Boy]. Nintendo, 1996.

[28] Minecraft. [Windows]. Mojang, 2009.

[29] Dark Souls. [PlayStation 3, Xbox 360]. Bandai Namco Entertainment, 2011.

[30] Donkey Kong. [Arcade]. Nintendo, 1981.

[31] Crash Bandicoot. [PlayStation]. Sony Interactive Entertainment, 1996.

[32] The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. [Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360]. Bethesda Softworks, 2011.

[33] Life is Strange. [Windows]. Square Enix, 2015.

[34] The Last of Us. [PlayStation 3]. Sony Computer Entertainment, 2013.

[35] Until Dawn. [PlayStation 4]. Sony Computer Entertainment, 2015.

[36] Hitman. [Windows, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360]. Square Enix, 2016.

[37] Bloodborne. [PlayStation 4]. Sony Computer Entertainment, 2015.

[38] Undertale. [Windows]. Toby Fox, 2015.

[39] The Walking Dead. [Windows]. Telltale Games, 2012.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)