Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Rejecting Black Boxes: Or - 'Punk Approaches to A.I. and Navigation for Spellrazor'

Fluttermind's Dene Carter suggests that the accepted solutions to A.I. problems are not always the best fit for your game.

Introduction of Manifest Pomposity

Far back in the mists of time, when games were a new thing, and nobody knew what they were doing, before 'best practices', 'accepted algorithms' and 'standard toolsets' and 'weird sets of words in quotes for no good reason', people were making some amazing games. Download Mame and - after deleting all but about 20 of the quadrillion games it comes with - you'll see that what you're left with is A-MAZING. No, really.

In those days, developers looked at their game's requirements and developed exactly what they needed. Nothing more, nothing less. Today, many developers solve their problems by putting together a gigantic lego-stack of black-boxed rendering, physics and A.I./Navigation technology, believing there is no reasonable alternative.

I'm going to suggest that there are alternatives to this approach. I'll focus on Spellrazor's A.I. in particular, and hopefully make you consider whether middleware, A* or State Machines are really necessary in your case.

A Butterfly's Inner World: Or 'Random Fable Anecdote'

In Fable 1 we had pretty little towns and villages filled with complex A.I. behaviour. Follow one person around a village for a full game-day. You'll be impressed.

Did you know that villagers get into bed? I don't mean just lie on top of the beds. I mean actually fold back the sheets and get into bed. No? That's because nobody ever went into houses at night because they were locked. Oh, you could break down the door but nobody ever did, and you'd get arrested if you were spotted anyway. We actually discouraged players from seeing it. (Note: we dropped the entire behaviour set for Fable 2, along with many others such as children's school days. Nobody noticed)

Earlier in the game's development we found out that the villager A.I. was taking a ridiculous amount of processing time. We added various logs and other debugging tools in order to track down the problem. It was only after someone's careless sword-swing smacked into a butterfly that we understood what was wrong.

The butterfly yelled 'Help' and then A* navigated its way to a village exit whereupon it disappeared up a trade-route.

Someone had made the default behaviour 'human'. I mention this as an illustration to hilight that 'Best' is not always 'Appropriate', though many would have you believe so. They should be flogged. Gently. With something moist.

Spellrazor: Or 'What Does Your Game Actually Need?'

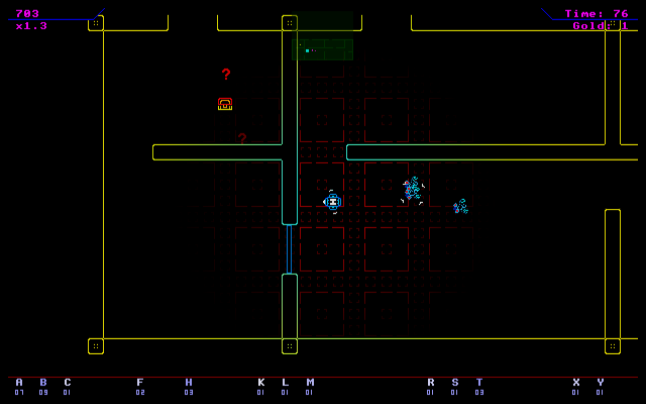

Spellrazor is my ridiculous 80s game resurrection project. It's a top-down rogue-lite dungeon shooter for PC and Mac with 27 fire buttons and a host of different enemies. The game goes into a kind of bullet-time when you're in danger, allowing you to use those those 27 spells tactically - even in the midst of a complex firefight.

Nono. Ignore the picture. It's not the same as actually playing the game in all its throbbing neon-tinged glory. Just pretend I didn't put the picture up at all. Yes, that's much better.

Spellrazor is of the same school of thought as old Williams classics like Robotron and Defender. It's sinister, it's deadly, and its enemies are total bastards.

When I started, I had a clear idea of what I wanted game-play to be like. I had a little scenario in my head that I used to test the suitability of anything I wanted to add:

"Okay - on the other side of this door there are 3 flies and a security bot. I'm out of [Z]ap, so... Oh! I have a [J]ump! I can hop over the wall and take out the flies, then use a single arrow followed by a [Q]uake to take out the Security! Here we go..."

I find this kind of exercise useful to figure out the verbs in the game. In Spellrazor's case 'Panic' actually came up too often, so I changed things around a bit. Anyhow, as you can guess from the description, it's a kind of 'breach and clear' game with plenty of opportunity for things to go horribly wrong. For this scenario to work, I required three things:

Player Awareness: the ability for players to assess a situation on the other side of a door

Player Action Choice: or else there's no decision-making and... no game!

Enemy Behaviour Differentiation: otherwise you'd just use one tactic for all enemies

There is no number 4. I said 3 things.

3) is super-important. It defines how players feel about and react to the different enemies. Differentiating them purely by weaponry or stats would be easy, but wouldn't lead to the rich diversity I required. I wanted enemies to think differently from the ground up.

Embracing Retro Simplicity: Or 'Zelda's Artificial Stupidity'

Seeing as I was in an 80s mindset, I didn't want to use A.I. that led to perfect behaviour. I wanted the retro-feel to permeate right through the game - after all, the low-tech approach was good enough for some of the best games ever made: Defender and Robotron. So it should be good enough for me, right?

But wait! Some of you are thinking 'But those games were really primitive! There's no justification for that kind of attitude now, in 2015'.

Okay, so how about Zelda? If you've played any Zelda game since Link to the Past, you have probably been impressed by the puzzle design, dungeon design, overall 'feel'. But what about the A.I.?

Can you remember being hit by an enemy other than a boss in Zelda? No? That's because they were games designed to make you feel good when Link hit or blocked an enemy and not the other way round. The last thing you want in a heroic quest is artificial intelligence that allows enemies to defeat you. If anything, heroic games require artificial stupidity; enemies arranging themselves to create the best, most heroic narrative possible, only providing the illusion of intelligence and some kind of understandable risk-reward. Remember the butterfly? Not that. See - I promised it would be relevant.

Most A.I. tutorials seem to work from the Platonic idea of creating 'perfection' in pathfinding and logic (in the form of 'A*' and Finite State Machines) with the assumption that you can always work back from this in order to create personality/flaws. While a perfectly usable approach, it isn't necessary, and is potentially an over-engineered solution for the problems of your game.

I'm going to illustrate this by describing the behaviour of a couple of Spellrazor's units.

Spellrazor: Or 'Using Map Generation to Your Advantage'

Spellrazor has a hierarchy of navigation.

1) Room/Door-based: moving between neighbouring rooms using doorways as targets

2) Tile/node based: moving from grid-square to grid-square at high or low granularity

3) Physics: acceleration, velocity and inertia

Using 1) requires 2) and 3), using 2) requires 3), and 3) can be used by itself. Paired with some simple behaviours, this is sufficient to create enemies that are satisfying to engage with in Spellrazor

Creatures have 3 notions: TargetPosition, GoalPosition, and - rarely - a Sidestep direction.

TargetPosition is the primary target's position (usually the player)

GoalPosition is the immediate next 'step'

Sidestep records the last direction used to avoid a blockage

In order to support these, I cached basic navigation data when I generated the map using BSP subdivision to create a set of linked rooms. (If BSP trees are not punk enough, then any method allowing you to remember which rooms are neighbours will work). Note, I didn't have to store this navigation data. I could have calculated it on the fly. Pre-caching each tile and node's neighbours speeds up processing.

After creation, my map hierarchy is:

Map - the whole 2d world. Made up of Rooms, Nodes and Tiles

Rooms - areas with position, width, height, and lists of doors and neighbours

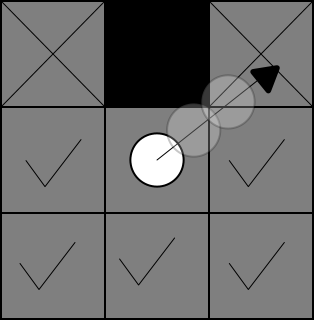

Nodes - Sets of 4x4 tiles. Holds information about navigability of neighbouring 8 nodes + self

Tiles - Smallest unit. Holds room i.d. and navigability of surrounding 8 tiles + self

Critically, evey node or tile that holds navigation information is processed to disallow diagonal neighbours that would cause creature boundaries to cross into the territory of other solid non-diagonal points. This stops enemies trying to move through a pillar just because the diagonal looks clear.

I'll now show how this information is used to elicit the appropriate behaviour for 3 enemies.

Fly - Physics Based Navigation Only

The fly is the simpest of the enemies. It is a little homing missile. It uses no navigation information at all.

The fly's behaviour is:

If unaware of target, look for random place in current room and head there using thrust + a random time-based angular wobble in order to approach it. This is offset for each fly so that they do not oscillate in unison.

If aware of target, rotate toward it, and add thrust + wobble

The fly's physics is 'heavy' - it has a wide minimum turning arc size, and a lot of inertia.

Flies tend to bunch up quite a lot and slide around corners (look at the original pic of Spellrazor). These swarms break up a little in open spaces due to the random angle osciallation. This is a good thing. It feels right.

Flies are fairly lethal as they are fast and tends to come in groups. These are formed due to their behaviour rather than intelligent placement.

Despite their simplicity, flies are satisfying to kill because players need to precisely control their positioning in order to accurately target them.

Swordsman - Tile Based Navigation

The swordsman is one of few enemies that require more than one hit to kill. It is also one of the deadliest, despite having no real notion of where it is in the map. However, because this game focuses on players hunting down enemies, this lack of intelligence doesn't matter!

The Swordsman's behaviour is:

If unaware of target, look for random neighbouring tile in a cardinal direction

If aware of target, it heads toward it in cardinal directions only (zig-zagging)

If within range of target and 'cooldown time' is zero, it swings its sword

Swordsmen move quickly, and - when in view - often force you to backtrack into an empty room. As soon as they break line-of-sight they revert back to random movement. Being able to withstand a hit means that trying to make this creature any more complex would be pointless, and allow fewer opportunities for the player to feel clever. Remember what I said about this being a 'breach and clear' game? Those are all about the player feeling clever.

Security - A Classic Navigator?

The Security bot is, by far, the nastiest enemy in the game. It teleports into the corner of the target's room, and once it has arrived, it follows the target mercilessly, belching out hundreds of bullets once in range. It is really nasty.

It is also the most complex A.I./Navigator. "Oho!" I hear you cry. Because you are an Edwardian gentleman. "Oho! I spy a case for complex navigation, perhaps even A*? You are bested!"

I'm sorry, Mr Mutton Chops. This is a punk article about punk coding. Take your weird elephant's foot umbrella stand, grab an absinthe and shush.

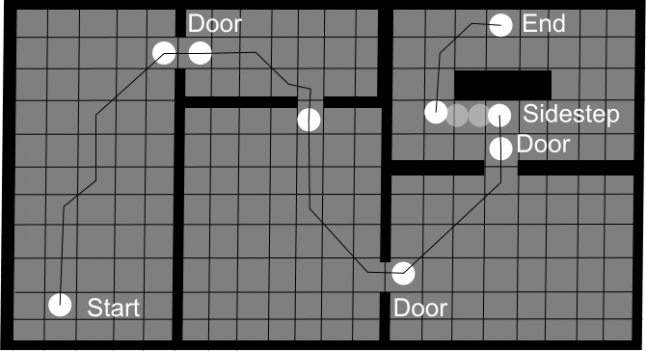

The above diagram is definitely not drawn in crayon. It does, however, illustrate the route and decision points of the Security bot, and how it gets between them.

Despite the apparent complexity, its rules are fairly simple:

If target is in the same room:

Try to move toward target.

If route is clear, move in that direction and clear the Sidestep direction

If blocked

If you have a Sidestep direction, and it is not blocked, keep going

If not, step to one side based on which move would best close the gap to the target. Remember this Sidestep direction.

If not in the same room as target, use a breadth-first search of rooms to find the next room to explore. Find the door connecting the two rooms. Make the far side of that door the goal position.

Now, because blockages are never dead-ends and the map is relatively simple (rectangular rooms with big chunks taken out of them to add detail) this simple behaviour results in a devastatingly smart foe. It tracks you across the entire map, yet only rarely does it think about anything other than the nodes immediately around it. Even when it does have to do a search, it's a breadth-first search of around 30 rooms and thus close to instantaneous.

You'll notice that even with this creature, there is no state-machine! The only extra detail recorded is the Sidestep direction.

Conclusion

At no point have I wished any of my enemies were smarter or more complex in their behaviour. Spellrazor isn't 'The Last of Us.' I'm not trying to convince the world that my little robots are people. They're not. They are dangerous little robots. They are predictable when necessary, and each requires very different approaches when encountered.

These are what Spellrazor needed, not what was proscribed by someone else's vision for another game entirely.

A Final Odd Music Analogy

I love early electronic music. I have a particular fondness for the work of Louis and Bebe Barron on the Forbidden Planet soundtrack.

The Barrons didn't have an orchestra or synthesizer at their disposal. Instead, they fashioned small, flawed circuits that often burned out while recording. They warbled, they whooped, they sputtered and crowed and nobody had ever heard anything like it.

I feel we've an opportunity to do the same thing now. The imperfections and flaws in our algorithms are part of our games' personalities and key to the punk developer spirit.

If Johnny Rotten could actually sing, the Sex Pistols would have been just another pop group. Our flaws should be embraced by ditching black boxes and actually learning to do stuff ourselves; messily, clumsily, but originally.

...if it's right for the game...

Spellrazor can be downloaded for free at: http://dene.itch.io/spellrazor

Dene Carter can be found on Twitter as @Fluttermind

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)