Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Playing with politics: How real-world politics could improve your game

Many game developers shy away from real-world politics in their virtual worlds, but taking inspiration from contemporary politics, history, and culture can make narratives richer, deeper, and more compelling.

Many game developers shy away from real-world politics in their virtual worlds, but taking inspiration from contemporary politics, history, and culture can make narratives richer, deeper, and more compelling. Papers Please and Orwell proved that politics-heavy games can be classics, but even a game that isn’t exclusively about politics can still be improved by adding them into the mix.

Nick Hagger is a co-founder of Robot Circus, an independent game studio based in Melbourne, Australia. After spending several years making games for third party clients such as the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and Disney, in 2017 they debuted their first original IP, a science fiction puzzle-RPG called Ticket to Earth. Its episodic story delves into themes of worker exploitation, government corruption, and guerrilla warfare. In this article, Nick talks about how even a fun, colourful tactics game made originally for bite-sized consumption on mobile was greatly enriched by taking inspiration from real-world politics and history, and how your game could too.

. . .

Making the unreal real

It’s a strange contradiction, but science fiction is always at its best when it feels real.

Star Wars, Alien, and Blade Runner were startling and compelling in large part because they took place in properly lived-in worlds, where stuff got dirty and worn out. Far from the perfect gleaming chrome and glass of classic science fiction, these were places that felt so real you could almost smell them. Video games can create that same sense of place, creating a sense of authenticity in fascinating interactive ways.

It goes deeper than that, though, down into the way characters behave and the things that are important to them. A video game can draw us into a world of faster-than-light travel and bizarre aliens and we’ll go along for the ride, but as soon as a character behaves in an illogical way our disbelief comes crashing down. Jetpacks and laser swords, we can deal with, but taking control away from the player in order to force a completely out of character decision, just because it’s convenient for the plot, will sever our connection to that imaginary world and force us to see that it’s just make-believe.

This is true of the societies that science fiction characters live in, sometimes resisting against them and other times trying to preserve them. These fictional social structures and governments might be fanciful, but they always work best and feel most compelling when they feel believable, and internally consistent. The timeless science fiction classics have always been those that show us reflections of ourselves, that tell us something about the real world through a fantastic filter.

Politics have to creep in eventually. You can’t really avoid politics, no matter how much people will try, because people create politics. Get a group of people together and give them reasons to interact, and political structures will start to emerge almost immediately. Even in a small group, people will find things they agree or disagree about. They will form alliances, hold grudges for past wrongs, and try to impose some kind of order. That’s what politics is, in essence.

If you want your science fiction world to feel real and compelling, you’re going to have to think about the political structures that exist within it. You will need to think about practical questions, like how law and order are managed, how interlopers are punished, and how leaders are appointed. All of these are inherently political, and if you want the societies and groups in your stories to ring true, then the best way to create the political structure is to take inspiration from the real world. This isn’t a bad thing: believable politics will make your world richer and more interesting, and help your audience to accept all the impossible things you throw at them.

Choosing the ingredients

When I started writing the broad story outline for Ticket to Earth, I wasn’t trying to make a statement or change the world. All I knew was that we had around 20 hours of gameplay and we needed to come up with a story and a cast of characters who would keep players engaged and motivated to keep playing. It was pure pragmatism to make characters I hoped players would care about, so they would keep playing through multiple levels to find out what happens to them next. Adding a political dimension to any world-building helps to establish a logic and coherence to the rules that exist within that world and bind the characters.

A lot of things went into the mix for Ticket to Earth apart from a plausible political structure. In a lot of ways it’s a very Australian game, drawing on contemporary Australian cinema but also the relatively brief history of European settlement in Australia. Everybody knows that the modern nation of Australia had its start when a bunch of largely non-violent petty criminals were transported to a distant land to create a cheap colonial workforce, but that pattern has repeated itself.

From "Razorback" (1984)

Most relevant to Ticket to Earth’s story of impoverished miners stranded on a distant world is the sometimes tragic history of Australia’s gold rushes. People came vast distances to try to make their fortune on the Australian goldfields, giving up everything they had in the hope of striking it rich, and it destroyed countless lives. The government of the day cruelly exploited gold miners, leaving many of them in desperate poverty, unable to leave because they couldn’t afford transport home. This desperation erupted into violence, most famously at the Eureka Stockade, where prospectors clashed with soldiers and dozens of people were killed.

From "Turkey Shoot" (1982)

We also drew heavily on Australian cinema of the 70s and 80s, which fearlessly explored science fiction themes on minuscule budgets. I like to think that Torcha, the pyromaniacal villain from Ticket to Earth episode 1, would have fit neatly into the Mad Max universe alongside Lord Humungus and Toe Cutter. Australia produced a lot of other post-apocalyptic cinema in that brief window, and other films that examined the isolation and loneliness of the Australian outback – The Last Wave, Razorback, Turkey Shoot, The Cars That Ate Paris, Long Weekend, and others – and these inspired many of the themes and emotions in Ticket to Earth.

From "Razorback" (1984)

Of course, we also wanted this to be a game that anyone could enjoy, not just Australians, so we created a universally understandable narrative with fun little nuggets of Australiana for local audiences to enjoy finding. Isolation and abandonment are Australian themes that resonate through our history and culture, but I think everyone has felt lonely and desperate at some time in their lives. We were all teenagers once, convinced that nobody would ever really understand us, afraid that we would never forge a meaningful connection with other people.

Maturing the medium

Perhaps some of the resistance to including real world politics in video games comes from the idea that games are, by their nature, playful and therefore un-serious. There’s a certain vintage of person that may view video games as a cultural oddity rather than a mainstream phenomenon, and to them the idea of a game tackling a serious topic is fraught with risk, because by definition games can’t deal with things seriously.

The thing is, I think we’ve reached a point where we have no choice but to start dealing with mature, meaningful topics in games. All narrative-based popular culture – novels, films, television, comics – reach a point where all of the easy stories have already been told, over and over again. Creators in these media run the risk of losing their audience if they keep trying to tell the same old stories, so it’s in their best interests to try talking about something new and different.

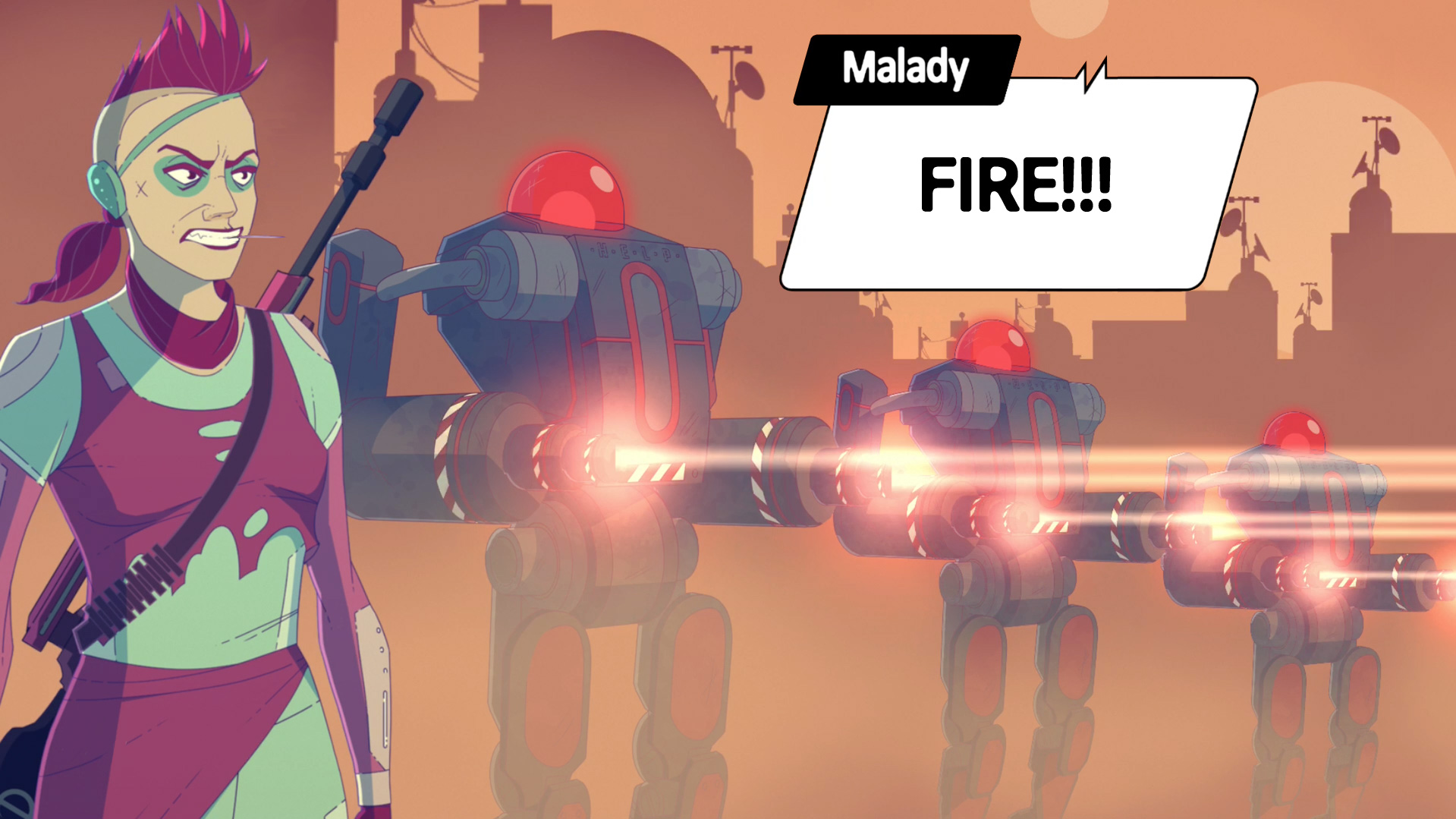

Games are a form of art and expression, and game developers have things to say. A few years ago I worked on a game called De Blob. Even though it was a fun, colourful, cartoony world, it was actually a very political game: it asked players if they would choose to live in a grey and colourless world of control and order, or if they will be the person who breaks the rules in order to create beauty and give people hope. Is it better to abide by the rules, even if the rules are unjust, or is it a just and moral act to break bad rules? It’s a simple enough question, sure, but it’s an inherently political one.

From "de Blob 2" (THQ)

Even the villains in Ticket to Earth have some moral complexity to them. In Episode 2: Crash we introduce a criminal militia called the Ghosts, who live out in the wasteland and illegally amass an arsenal of guns. At first they seem like pretty standard bad guys, but if you take the time to explore their story, you will find that they are victims of corporate greed. They are dying from the industrial poisons they ingested working in the mines, but the government and the corporation (who in this world are essentially one and the same) refused to help them. There is no cure for their condition, and the drugs that could prolong their lives and ease some of their suffering are too expensive for most people to afford.

I’m not going to defend the villains of Ticket to Earth, because the lengths they go to in order to seek their own definition of justice are monstrous, but it was important to us that they would also be believable and sympathetic to some degree. We want players to think, “What they did was evil and terrible, but I can sort of understand why they did it.” In my opinion, moustache-twirling villains who are evil for the sake of being evil just aren’t very interesting. The best villains are the ones who think they’re actually the hero – just look at Magneto for proof of that!

Citizens of the future

Some people might consider our choice of protagonist to be political, too. In a video game landscape that is still dominated by square-jawed white men, you will always invite comment and interpretation when you centre your game around a dark-skinned, same-sex attracted woman. For me, though, it was just who she needed to be. Rose is a citizen of the future. I would like to think that in the future there is nothing controversial about Rose; she’s a regular person who has made completely normal choices. She’s a member of her community, valued for what she contributes, and the life she leads and the person she chooses to love is immaterial.

To me, the more interesting thing about Rose is her distaste for violence. It was an interesting challenge, in a game that involves a lot of fighting and killing, to write a plausible heroine who takes no joy from what she is forced to do. There is a moment early in the game where, after fighting bugs and robots for the first few missions, she kills a human being for the first time. The game stops for a moment while Rose reacts with horror at what she has done. This scene was incredibly hard to write, and it went through dozens of iterations until we found a good balance and tone.

It’s hard to strike the balance between “why am I doing this, even though I am continuing to” – which is cheesy and doesn’t resolve anything – and actually finding your character questioning their situation and recognising that they have no choice but to defend themselves. In doing this, Rose is drawn into a system of bounty hunting where she is paid money to kill, and it was important to us that she maintain her distaste for such a system.

Above all we wanted her to be someone that players would feel kinship for regardless of who they are. We certainly hope that LGBT players will find some inspiration seeing a character who is like them, as a compassionate, moral, and strong hero, and that all players will be drawn to her as a compelling and authentic character. One of the things I love most about Rose is that she’s a child of her community: being an orphan whose parents were killed in an industrial accident, she was raised by her whole town. I love how she sees her entire community as her family, and it is protecting them from harm that drives her to take up a weapon and fight.

This is why we fight

Ultimately, I think that is where believable political structures will strengthen a game’s narrative: they tell the player “this is why we fight”. Fun game mechanics will only carry us so far, and eventually we will need a reason to keep playing, to keep exploring a virtual world, beyond “this is fun”. Politics are tied up in the things that motivate people, and if we truly believe in and care about the heroes of a story, then what motivates them will motivate us too.

. . .

Ticket to Earth is a unique hybrid of turn-based tactical combat, colour-matching puzzle game, and team-management RPG, released episodically on iOS, Windows PC, and Mac and coming soon to Android. For the latest news on this game and other Robot Circus projects, follow them on Twitter.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)