Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his regular 'Persuasive Games' column, designer/writer Bogost looks at the history of the prank in video games - from Easter Eggs through Sim Copter and Syobon Action, with particular reference to Gareth's stapler.

In one of the many memorable moments of Ricky Gervais's BBC television series The Office, troublemaker Tim encases Gareth's stapler in Jell-O. Gareth is annoyed, and the viewer is amused, because both comprehend the act immediately: it is a prank.

Pranks are a type of dark humor that trace a razor's edge between amusement and injury. The risks inherent to pranks contribute to our enjoyment of them.

This includes the risk of getting caught in the act, or the risk that the object of the prank might become hurt or insulted. And yet, this risk also gives pranks their social power. Because he risks blame, the prankster affirms his relationship to the victim.

The same is true when the victim chooses to laugh the prank off rather than to mope. If that victim chooses to retaliate later, the result is not spite but a playful type of social bonding.

One obvious connection between pranks and video games are tricks developers play on their employers or publishers. The easter egg is one example. An easter egg, of course, is a hidden message in media of all kinds, from movies to games. In software, ester eggs are usually triggered obscure sequences of commands, such as the hidden flight simulator in Microsoft Excel 97.

Software easter eggs arose partly in response to the cold anonymity of the computer, and the first video game easter egg had precisely this problem in mind. In the late 1970s, Atari engineers created titles for the Atari VCS singlehandedly, from concept to completion.

Despite their undeniable role as authors of these games, the company did not publish credits on the box, cartridge, or manual. When Warren Robinett completed the classic graphical adventure Adventure in 1978, he included a hidden room with graphics that read, "Created by Warren Robinett."

The process of discovering the hidden message was complex and unintuitive, although not difficult enough that it couldn't be done.

Atari learned of the prank when a 15 year-old player wrote the company a letter about it. It was never removed from the game, and Atari even used the gag to their own benefit, spinning it as a "secret message" in the first issue of fan magazine Atari Age.

Soon enough, higher-ups embraced the easter egg as a way of deepening players' relationships with their titles. Howard Scott Warshaw's inclusion of his initials in 1982's Yars' Revenge was fully endorsed by management.

A more controversial prank can be found in SimCopter, a 1996 Maxis title that lets players fly helicopter missions around the cities they create in SimCity 2000. Developer Jacques Servin secretly added speedo-clad male bimbos (Servin called them "himbos") who would meander the city and passionately kiss on certain calendar dates. Servin cited unfavorable working conditions as an inspiration for the prank, and he was subsequently fired.

This was just the start of pranking for Servin, who has since made a practice of public interventions as a member of the subversive activist collectives The Yes Men and RTMark.

Despite their clear status as prank, easter eggs play jokes on the game's sponsors or publishers but do not turn the games themselves into pranks. To find games that play practical jokes on their players, we'll have to turn to pranks of another sort.

Many pranks function by subtlety rather than flamboyance: connecting a coworker's paper clips together so they pull out of a drawer in a long chain; switch the "push" and "pull" signs on an outside door; taping over the laser eye of an optical mouse so it doesn't work; tying someone's shoelaces together.

These small-scale pranks are probably the commonest type; they don't require significant preparation, yet they can facilitate an ongoing feud among participants. The set-up and follow-through of small-scale tricks can even take on a playfulness that resembles a game.

At the office, these activities revolve around limited resources. One might hide or move supplies of particular worth, or plot to arrive at the office early to lock a coworker out of the best parking spaces.

Perhaps it is no surprise that these topics might translate directly into games that let players play pranks on each other, through the game itself. Take parking, a strange and complex social activity that Area/Code adapted into the Facebook game Parking Wars.

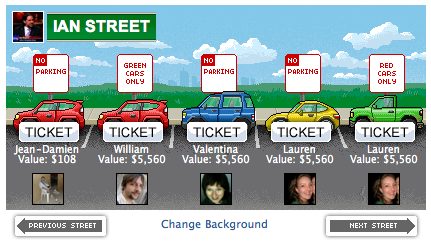

In Parking Wars, each player gets a street with several spaces as well as a handful of cars, which come in different colors. Play involves virtually parking these cars on the streets of one's Facebook friends. Each car earns money by remaining parked on the street over time, but the player can only cash out a car's value by moving it to another space. Players level up at specific dollar figures, earning new cars as they do so.

Some spaces have special rules, like "red cars only," or "no parking allowed." It's possible to park illegally in these spaces, but if their owners catch you they can choose to issue a ticket, which tows the player from the space and forfeits the money earned to the space's owner.

When possible, it's best to park legally. However, in practice this isn't easy, since many players vie for the limited resources of their friends' collective parking lots, just like we do with our coworkers at the office. Moreover, very occasionally the signs on spaces change, so no one's guaranteed to be safe.

Playing Parking Wars is an exercise in predicting friends' schedules. A colleague in Europe is likely to be sleeping during the evening in the States, and thus his street might offer safe haven at that hour.

And just as some meter-maids don't get around to patrolling real streets, so some players of Parking Wars don't get around to patrolling their virtual one. Of course, such players might just be busy, or they might even be baiting their colleagues so that they can later issue a whirlwind of unexpected tickets.

Receiving a ticket in Parking Wars isn't a prank on the level of spreading dog poo on the underside of a buddy's car door handle. Rather, the combination of latent, ongoing play and occasional "gotchas" makes plays in Parking Wars feel like pranks.

The game weaves its way into the player's ordinary use of Facebook, rather than requiring complete immersion. This latency creates a credible context for surprises, just as the flow of the work day sets the stage for switched desk drawers or shoe polish-smeared telephone receivers.

Gotchas come in at least two forms: in giving or receiving a ticket (which pops up as a big, yellow overlay across the screen), and in the silent knowledge of having taken advantage of another player's inattention.

Many games give players the opportunity to trick, fool, or swindle an opponent out of resources -- just recall the pleasure of seeing an opponent land on a particularly valuable property in Monopoly. But in Parking Wars, players aren't always expecting it. By setting up an ordinary social environment for disruption, Parking Wars becomes a medium for pranks, a kind of video game whoopie cushion.

A prank like Tim's in the first episode of The Office brings us pleasure because it requires a very involved setup that cashes out in only a few moments of amusement. It also amuses us because we can imagine all the work Gareth has to do to retrieve his stapler -- unearthing it from the jelly mound, soaking it in hot water to remove the excess.

Other pranks on this scale include covering someone's entire office in aluminum foil, or drywalling over the boss's door, or filling a coworker's cubicle with packing peanuts.

The office is a popular venue for pranks. We're stuck there most of the day, every day, by necessity more than by choice. Moreover, we have little, if any, control over our fates during the workday; the worker's time is supposed to be spent at labor, efficiently producing widgets or moving information.

We prank at work to exert agency in an otherwise uncontrollable environment. As with Robinett's easter egg, office pranks help their perpetrators exert their humanity in an age of industry. But moreso, pranks offer an opportunity to undermine the very values of the office.

Consider again the world of The Office. The workers depicted in the show push paper in two ways: first in the usual sense of mindless tasks, and second in the literal peddling of office paper, the business of the show's fictional company.

The jelly-bound stapler draws our attention to the blind pushing of papers, and sets the stage for the social critique that follows in subsequent episodes. The prank is what the show is about.

Historically, there are many examples of pranks as confrontational responses to social and cultural situations.

Historically, there are many examples of pranks as confrontational responses to social and cultural situations.

The avant garde arts movement Dada supported anti-art such as the nonsense poetry of Tristan Tzara and the found art of Marcel Duchamp.

The movement's proponents argued in their manifestos that if contemporary art partook of the same rationalist ideals that had plunged Europe into World War I, then those artistic values must be rejected.

In the 1950s, the beat concept of the Happening popularized made public performance art, a concept the Situationists made political in the 1960s. The "situation" used public performance to critique the foundations of everyday life upon which it relied.

Situations helped lay the cultural groundwork for more recent public pranks like flash mobs, which often draw attention to the ways public space has become privatized or monitored.

Pranks like situations and flash mobs first amuse, or distract, or disturb just like any other gag. But they also dig down into the very conventions of their subjects, laying them bare in mockery and derision. Dada pranks art to uncover its affectations. Television parodies like The Daily Show and The Colbert Report prank broadcast shows to undermine those show's pretenses.

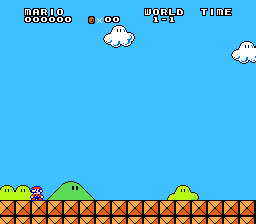

Some games attempt to do something similar to the very conventions of gameplay. One is Myfanwy Ashmore's Mario Battle No. 1, a hack of the Super Mario Bros. NES cartridge in which all platforms, enemies, and objects have been removed, resulting in an empty expanse with no goals and no challenges. When time runs out, Mario dies.

By laying the architecture of the game bare, Mario Battle No. 1 invites the player to ask deeper questions in their absence: where do the Goombas come from? Do they serve Bowser willingly?

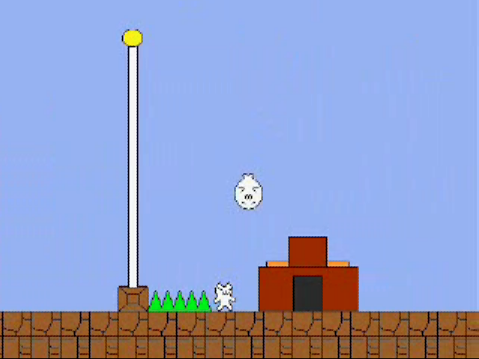

But Mario Battle No. 1 is more art object than video game prank; it is not really playable as a game, at least in the same way The Daily Show is viewable as television. A better example of a game convention prank is Syobon Action, a Japanese platformer also known in the West as Cat-Mario or simply "Mario from Hell."

The game is playable, challenging, and enjoyable, but it is constructed in a way that defies every expectation of Mario-style platform conventions.

In Syobon Action, the floor sometimes falls away unexpectedly. An invisible coin-box appears as the player attempts to jump a chasm, hurtling him down into it instead.

A bullet fires from an unseen source off-screen just in time to knock the player from the most direct trajectory across an obstacle. Hidden blocks trap the player if he doesn't take a counter-intuitive path. Spikes randomly extrude from some surfaces after the player steps on them.

The genius of the game -- and what makes it a prank -- is that it systematically disrupts every expected convention of 2D platform gameplay. Instead of making many approaches to a problem work equally, the game demands that the player undertake bizarre and arbitrary routes. It punishes rather than rewards collection.

The genius of the game -- and what makes it a prank -- is that it systematically disrupts every expected convention of 2D platform gameplay. Instead of making many approaches to a problem work equally, the game demands that the player undertake bizarre and arbitrary routes. It punishes rather than rewards collection.

In addition to coins and power-ups, enemies sometimes pop out of question-mark blocks.The rules change: sometimes a mushroom acts as a power-up, other times it turns the player into a robot that crashes through the floor and dies. The game takes control away from the player and uses carefully timed trickery to make decisions that would be reasonable in the original game require complete rethinking.

For example, the game preserves the end-level flagpole characteristic to Super Mario Bros, but in perverse distortion. Just as the player jumps off the ledge toward the flagpole, a long projectile streaks across the screen; the only way to avoid it is to backtrack onto the ledge again to jump over it.

After successfully mounting the flagpole, the game takes control of the player character and moves it toward the castle, just as in Super Mario Bros. But a carefully timed enemy falls from the sky, colliding with and killing the player. Success comes only when the player jumps over the flagpole, avoids the resulting enemy, and then backtracks to complete the level.

Complex pranks like the jelly stapler, the foil-wrapped office, and the unconventional platformer are amusing when witnessed and annoying when experienced. But they are also political. By mocking the rules we don't otherwise question, they possess carnivalesque qualities; they allow us to suspend our ordinary lives and to look at them from a different perspective.

It's possible to pass Syobon Action off on a friend as a legitimate Mario clone, only to laugh uproariously when things start to go wrong. This is the garlic-flavored gum usage of the game. But it's also possible to let Syobon Action prank you willingly, as a player, to stop and reflect on the conventions of platform play that have become so familiar that they seem second nature.

Like Tim's stapler gag mocks the values of office productivity, Syobon Action indicts the specialized language of video game geekery. This is the Dadaist usage of the game.

As video games expand in influence and application, the opportunity to prank friends, coworkers, housemates, and family members in video game form will surely increase. But part of the momentum required to carry out a prank is in its customization.

Parking Wars is a commercial effort, funded by A&E as an advergame to promote a television series of the same name. But Syobon Action is an independent title, a curiosity produced for its own sake and at great effort. The future of video game pranks relies on a number of literacies that are not yet well-developed. Video game pranksters must have the know-how to make games and to integrate prankish ideas into them.

Despite current trends toward "user-generated" games based on templates and wizards, a much deeper fluency with game conventions, tools, and craft will be required for video game pranks to become a going concern. They are commercially inviable in large part, but socially meaningful, worth the effort even if they disappear, like the Jell-O that melts when Gareth retrieves his stapler.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like