Part 2, Narrative bridging on testing an experience

Follow the building of a framework on how to approach the testing of an experience that concerns engagement, emotions and learning, pacing and control, from a narrative and cognitive perspective beyond structures and templates.

The reason for the initiative to write the series "Narrative bridging on testing an experience" that consists of three parts, which can be found at Narrative construction, is due to a long engagement as an artist to forward the narrative as a cognitive process within digital media. Since my relation to science from when I studied Computer science is complicated due to an academic resistance to study the narrative beyond structures and templates, based on a question from a student (and due to the lack of viable advice) I started to write the series. Why I share the series at Gamasutra is that I hope for a collective step to move the understanding of the narrative further. If you have missed the first part, it can be found on Gamasutra (here) or at Narrative construction (here).

I wonder if you remember the feeling that slowly came over you when you wrote what would become your last letter to Santa? If you have never written to Santa, or you are still writing, maybe you have the experience of buying a lottery ticket and is thus able to recognize the feeling of doubt when questioning your beliefs, intentions, and desires, as to why you are putting hopes into something you know won't correspond to your desires? The feeling I´m trying to describe is the same I have every time I return to science in matters that concern the narrative, which is complicated, to say the least. So in January, I decided to settle the relationship, with the same confidence I had when writing my last letter to Santa I wrote my last words to science (see “Are you a man or a mouse.”).

When I received a question at the beginning of the summer from a student who wondered how to assure the quality of an experience from a narrative perspective beyond structures and templates, I immediately understood the reason why the student asked. As there isn´t any viable advice within game research programs on how to construct narrative others than the structures and templates that are based on our ancestral creator´s messages from the past, I began to write the first part of the series (which can be found here). Carefully I started to decouple the structures from the narrative to enable building a framework that could show how our learning, engagement, emotions connect to narrative construction as a cognitive process.

When I was ready to post the second part of the series as to provide a framework on testing the experience from a narrative perspective, something unexpected happened, which had an instant George Martin effect on me. In the same manner, as George Martin told HBO, I told the student how this version of Game of Thrones would end, as what happened was that I had received a letter from Santa. Even though we feel what science says and does has nothing to do with our practice in the creation of experiences in digital media, this time it does. What I had received in my hands was the missing piece that could tell us about the most well-kept secret of humanity, which is how the human mind and thinking works.

The reason why we are holding on to structures and templates from our ancestral creators as if they were old family recipes from the past is due to that science hasn´t focused on the human thinking and learning separated from the animals´ since Darwin presented his theory of evolution. Since no one has, as of yet, seen animals making films, writing stories, creating games, technology, AI, weapons, or used tools to teach large groups of children, the human ability to create meaning based on desires, intentions, and beliefs, has remained uncharted. What this means is that everything concerning the creation of meaning based on beliefs, intentions, and desires, as for example the millions of letters to Santa and the feelings of doubts, hopes, excitement, and disappointments, have been lying there unexplored as they can´t be proved other than the arbitrary activities of illusions.

So the experiences and knowledge we have in the form of advice from our ancestral creators as the templates from the “Hero´s Journey”, and structures of a dramatic story arc are basically the only thing we have, which has been forward as a tacit knowledge through generations. However, what the templates and structures can do is to give us an idea of what has engaged the human through history and still does as the hero´s fight against power, and the hope that Santa will hear us.

Charles Darwin

In Darwin´s defense, he never said anything about human origin when presenting his theory of evolution. Instead, it was a new group of scientists – the psychologists – who embraced the task in the late 19th century to trace the human origin. Encouraged to break new ground, due to that the Western culture started to send children to school during the industrialization, the psychologists came to diminish the human thinking and learning into an instinct-driven organism. In this way the human learning and motivation came to be compared with animals, and where needs, stimuli, and responses from rewards and punishment, based on instrumental tests, began to form the dominating motivation theory called behaviorism.

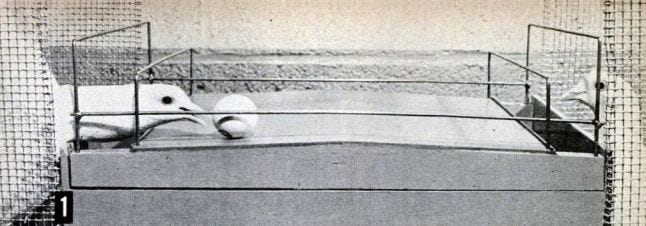

Yet authorities could see how the rewarding of behavior was the most effective way to make people perform. If considering the picture below from the 50s, which shows a test performed by the psychologist B.F Skinner proving his hypothesis to be true by rewarding pigeons to butt a ball to past the other pigeon. The problem with behaviorism is that it requires an external force to direct and decide which behavior to be desired and rewarded. And as no one would ever think of asking the pigeons how they would like to have their meal served, the same approach counted for humans: no fun before pulling a lever or butting a ball (oh, that is fun, but maybe not in a lab with a Ping-Pong ball directed by B.F Skinner).

Image provided courtesy of www.all-about-psychology.com/

The reason why I speak about narrative construction as I do and why I was able to build the thought-based method Narrative bridging was thanks to a group of scientists who have struggled since after the Second World War to humanize science by removing the behavioristic view.

One of the persons who belong to a younger generation of “humanization-scientists” is Peter Gärdenfors, a professor in cognitive science at Lund´s University. When I talked to Gärdenfors three years ago, he told me that he had been to South Africa. With a team of archeologists (I conjured a picture of an Indiana Jones while listening) they had found proof of human learning. Great, I thought. However, I didn´t understand how great it was until I found the results in an article this summer, which was also what should become the letter from Santa that added the last piece to the puzzle.

Through defining the human as the only species that has developed technology and from the tracking of early hunting weapons as stabbing spears, throwing spears, bows, poisoned arrows, snares, etc., Marlize Lombard, professor in Stone Age archeology, and Peter Gärdenfors could separate the more complex grades of causal thinking of the human from the animals. From the findings, they created a model of seven grade scale of reasoning (7-grade model), which separates the human thinking and learning from the animals. What Lombard and Gärdenfors basically did in the article: “Tracking the evolution of causal cognition in humans” (2017) was to tell science to travel back in time and add the missing piece to Darwin´s theory of evolution as to understand the human origin beyond the animal learning paradigm.

What the 7-grade model can do for us who are working within human interaction and human-computer interaction is to give us an idea when asking who, when, where, why and how when giving the design to experiences is what is happening in our minds. What this means to everyone who works with the creation of meaning, learning, emotions, attention, and engagement is that all the activities that are involved when we, for example, write letters to Santa and sharing feelings and thoughts based on beliefs, intentions, and desires, can be understood. We can also identify our thinking about others thinking, and be able to understand on what grounds we are basing our practice, concepts, terms and methods on in the creation of a meaningful experience beyond instrumental tests based on instincts and goal-oriented needs from a direct visual agent-object encounter. But the best of all is that we can speak about the most well-kept secret of humanity - our ability of mindreading.

---

If you would like to take a break in the reading, this is a good time, as from here I will start building a framework from which one can approach the testing of an experience that relates to our engagement, emotions and learning and how to think in terms of pacing and control from a narrative and cognitive perspective.

---

The super-ability of mindreading

Illustration by Linnea Österberg

If mindreading sounds like a suspicious activity, it´s because academia has told us so. As the truth has been held high and where the human ability of reasoning and constructing narratives have posed the opposite, even if the only thing I´m doing on this site is to speak about mindreading, I won't dare to use the term, as to not risk ending up at the funhouse (as who would rescue grandma then?). But why scientists haven´t been more curious about the studying of our ability to think separated from the animals is a mystery. Since who wouldn´t like to understand the creation of a Ping-pong game for pigeons by asking since when has animals ever constructed a game for other species?

So instead of waiting for science to take a seat in the time machine as to add the missing piece about how our reasoning works, I´ve planned on putting grandmother in the back seat and do an informal test-drive of the 7-grade model of reasoning (which means I reserve the right to act with an artistic liberty to the academic rules), as to see what mindreading (also called "theory of mind") can tell us about how engagement, emotions, and expectations relate to our learning and the pacing of an experience and the feeling of control (and if you wonder who grandmother is, the answer can be found in the previous part - here).

Connecting engagement to mindreading

One of the lower grades (the 3rd) of mindreading that doesn´t require much effort is that we can see a person that moves towards a fridge, and without knowing or speaking to the person, based on our experience and knowledge that others are thinking like ourselves, we can infer that the person is hungry and is going to eat.

For a narrative constructor the mindreading is about the same as for everyone else, but with the exception that the narrative constructor has chosen to make it into living to understand people´s intentions. If we take a look at the intentions behind a narrative constructor´s mindreading as to attract other´s attention. Suppose we let the person who is expected to take food from the fridge suddenly move the fridge, we would create a surprise.

If we are thinking about a surprise as a strong emotional reaction where people scream (see also the “The surprising scream of learning”), it can be hard to detect the more fine grades of cognitive activities that are triggered by a surprise. Yet, when experiencing a surprise, what happens on a cognitive level is that our mindreading shows to be incorrect. This means that we will adjust our hypothesis by adding the new experience to our memory. In this way we are building experiences and knowledge by adding the experiences on each other as a never-ending pattern and where the moving of a fridge will be categorized as a template of “possible-fridge-behaviours” (see also “Narrative patterns of thinking”). From a narrative constructor´s perspective, the adding of a surprise to the memory means that we have to come up with something new if we would like to engage/surprise again (see also “2 plus 2 but not 4”).

As I hope the fridge example gave you an idea of what mindreading means and how engagement from a surprise triggers our causal understanding and where the new information is added to our memory, I´m about to take a step further so we can understand how emotions relate to the surprise.

Connecting emotions to mindreading

As I have described in earlier texts how narrative constructors create surprises by presenting something unfamiliar in relation to the familiar (unknown/known, unexpected/excepted, etc.) that becomes like a vent for our emotions, which the constructor holds back and opens up, hold back, and so on. If we think about the surprise as learning and how it engages our emotions, it gets a lot easier to understand that it doesn´t need to be a conflicting drama to increase the emotional engagement, and how a fridge works just fine.

As to get an idea of how the adding of the experience connects to our emotions, one can describe the emotions connected to our learning as a radiator that is heating up when we learn and cooling down when we come to an inference.

Radiator by John Sheldon Flickr

As the understanding of causal behaviors is one of the keys to engagement and where we like to understand, we also like to regulate the radiator towards an understanding as it brings a feeling of relief when things make sense or are sorted out, etc. One example of technology that can be seen due to this need is that all the security we are surrounding us with, which makes us able to relax our causal understanding of eventual risks that can surprise and heat up the radiator.

Since a narrative constructor can spin the narrative vehicle of construction in a positive and negative direction, it´s important to show respect to the regulations of the radiator. As when a narrative construction can become negative is if we let someone run into surprises and before the person can organize the hypothesis and come to inference we add another surprise and another. In this way, we don´t give a person a chance to come to an inference, which means that we are decreasing the ability to learn. An example of this can be seen in the world when for example an authority is confusing people by not making sense, which can lead to misunderstandings, prejudices, or conflicts (on all levels) as people are trying to find meaning as to regulate the radiators that are heated up.

The interesting is that a positive construction of narrative can also heat up the radiators. But what differs negative heating of the radiators with a positive is the opposite, which means that one cares for the learning, which means that if one heats up the radiators, one takes the responsibility by returning the possibility to people to come to an understanding. Even though people couldn´t take a shower, seeing birds or listening to screeching violins, and where I´m sure that the fridge in the hands of Alfred Hitchcock would heat up the radiators; what made Hitchcock´s narrative construction to be of a positive kind was due the fact that he cared about our learning, which can be seen in how he paced the learning with respect to the need to feel in control, by means of letting people come to an inference (understand).

Yet Hitchcock took the control from the audience by exposing them to surprises, he always returned the control by letting the audience, from their hypothesizing and inferences, add a new experience to their memory. The new experience was then brought by the audience when returning to see the next film with the expectations of learning something new (by being surprised with something new). In this way, the exchange of experiences through mindreading was reciprocally shared between Hitchcock and the audience, and where they collaborated in the building of new collective experiences and expectations.

Looking from the perspective of fostering people and where rewards and punishments since ancient times have been the dominating theory of motivation on people´s performance, Hitchcock also fostered people when telling them to show up in time to see “Psycho” as otherwise, they would have to wait for the next shows as the doors would be locked. However, since the belief that contexts as entertainment and education are like two different hats we put on and where the genre of horror is considered to be separated from the school since schools belong to the pattern of “not-being-entertainment-and-contains-safety.” As the horror and the emotions of fear can also be experienced in school, the interesting is to understand how Hitchcock managed to foster people to get in time to the show, beyond genres and contexts.

From the perspective of the radiator, and our need to understand, the reason why Hitchcock told people to keep the time was due to that the audience in the 50s used to drop in at the end of a film and then stayed until the next show to see the beginning. How we can understand Hitchcock´s care about our learning, and how he managed to change behavior, was due to that people could understand the meaning from the exchange of experiences and expectations - as for how could they be scared/learn if not following the shared agreement. In this way, the changed behavior of arriving on time became meaningful from the simple fact that it made sense.

Reversed (which will make sense later on in the text why I bring it up here), if knowing that it´s to be expected that people can be late, to not accept the fact and hold on to the idea that punishment can change a behavior (which hasn´t worked so far), a dilemma will occur. As if you want someone to learn math and the person is late. If the person “has to wait to the next show” by being locked out, what differ Hitchcock from the teacher´s approach is that the teacher creates two meanings that don´t make sense as the person won't learn math, but learns that to learn math one needs to be on time, which is not math. Instead, it is learning about how the school works. And if the school rewards the learning about the school instead of why math is worth learning, it can also explain how it can affect the radiators to remember the school as a negative, but with some glints of joy when the learning made sense and recess felt boring.

---

But if you feel like having a break as to ponder about engagement and emotions, this is a good time before I continue to connect mindreading to mindreading (the communication between minds) by increasing the grade of mindreading with the help from the 7-grade model.

---

Connecting mindreading to mindreading

Since we brought in Hitchcock who raised the grade of mindreading and the level of engagement, I think we are about to leave the 4th grade that is: "being able to reason from effects to nonpresent causes seems to be unique to humans" (Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017).

Even if it is interesting to compare our thinking with the animals, and depending on our experiences, it can be easier for some of us to read the mind of a dog or a chimpanzee than an iguana. However, as the interesting thing is that we are reading other's minds (including animals), the communication between minds can with the help of the 7-grade model be understood as force transmissions in space and time (according to the 6th grade). As I have explicitly described in earlier texts the exchange of thoughts between the narrative constructor´s plotting of an experience and the perceiver´s learning about the plotting (see “Part 3 Don´t show, involve”), the 7-grade model certainly makes it smoother to describe how the exchange of thoughts work as we can decouple our reasoning from contexts, structures, genres, and other patterns that hinder us from seeing how beliefs affect our actions and emotions.

So if we continue in the same manner as with the fridge, where we created a surprise. Suppose we are looking at a plate of leftovers. Without hearing or seeing anyone we can infer that someone has been hungry, taken food from a fridge, made a dish and eaten the food. From the inanimate object of a plate, we can trace the forces of causes and direct our attention, based on our experiences, towards a person who is not even present.

When conjuring a memory that we have learned, the emotion from the experience explains why a flavor, smell, image, or plate can turn on the radiator while conjuring memories. In narrative theory, an element as inanimate objects is called a motif, which you give a function so it can conjure emotions and memories in people´s minds that makes them react and act. As we can decouple our reasoning with the 7-grade model from structures, contexts, etc. it is easier to see how our thoughts can travel in time and space in an exchange of cognitive triggers, which are referred to as forces in the 7-grade model, that can turn into causal counterforces. One classic example is the shower curtain in “Psycho”, which Hitchcock conjured from his mindreading, and where a seventy-year-old film can suddenly become a surprising force that appears in our daily shower routines, which makes the radiator turning on. To regulate and soothe the radiator, it can lead to that as a counterforce that we will have a new shower curtain later on in the evening that we can see through when having a shower the next day. In this way, we can see how mindreading can connect to mindreading in the most remarkable ways. And if you would like to know where the narrative constructor has its office, it is right here where forces and counterforces are crossing in time and space (see also “What it´s like to have the office in people´s heads”).

Shower curtain by DieselDemon Flickr

Since the horror genre makes us conjure strong patterns that affect our emotions, I will return to the plate of leftovers as to see how we can understand the more fine nuances, as we did with the surprise from the “fridge-movement”, in order to see how we can understand a longer duration of an engagement from the perspective of mindreading.

Let´s say that we change perspective from the “plate-finder” to look at the mindreading of the person who left the plate. What the person who left the plate can do when using the mindreading on a distance (also known as the act of imagining), is that he or she can “see” things before they happen, and know, before the “plate-finder” knows, how the “plate-finder” will react when seeing the plate of leftovers. Based on the beliefs of knowing what will happen, even if they haven´t happened, the “plate-leaver” can make an inference and keep away from the "plate-finder" due to increased emotions of anxiety. While staying away from the “plate-finder”, based on beliefs, the hypothesizing will continue until he or she can come to an inference that soothes the radiator to cool down, which will indicate a feeling of control that will make the person who left the plate returning to the “plate-finder”.

As we might wonder why a plate of leftovers can cause such anxiety. Let´s say that we meet the "plate-leaver" at a café while the mindreading about the plate of leftovers is in the process and we ask what he or she is up to. Depending on a new mindreading directed towards us, we are likely to hear the person constructing a narrative that will give the behavior a meaning. It doesn´t have to be true as it´s up to each person to make an inference about someone else´s mindreading, as who are we and what meanings will we create from hearing about the plate? However, if we would like to make a "Hitchcock-construction" and, in passing, put a plate of leftovers in front of the "plate-leaver" at the cafe, we would probably refresh memories and emotions and extend the duration of mindreading.

But as we are not making a horror movie about a plate of leftovers (which I will save for the director´s cut of this series), we will let the “plate-leaver” return to the "plate-finder". Assume that none of the hypotheses from the mindreading that kept the "plate-leaver" away was correct, what will happen is that a positive surprise will be added to the “plate-leaver´s” pattern of "not-having-to-worry-about-leaving a plate-again". Though we like the feeling of relief from the radiator when we understand, we are most likely to seek the positive feeling from the control again (unless we want to check if the inferences were correct by rechallenging the "plate-finder").

What I deliberately did in the description of the “plate-leaver´s” mindreading with the help of the 7-grade model was to detach the reasoning from one specific thing – the experiences. The reason was to show, in the same way as with the surprise and the “fridge-movement”, how the creation of suspense works from the perspective of learning. What suspense does is to increase the length of the engagement. As I never defined in the description of how long the “plate-leaver” stayed away from the “plate-finder”, and where I made us meet the "plate-leaver" at a cafe. How long would you say the “plate-leaver” spent on reasoning away from the “plate-finder”?

Why I asked how long time you thought the “plate-leaver” could have been away was to give you an insight about how a narrative constructor´s mindreading works when deciding with what pace the perceiver gets to learn (understand), as this is tightly connected to the radiator and the beliefs the perceiver is building. But if I decide to set the time to three hours from that, the “plate-leaver” left the plate, met us, and returned, what we can see from the perspective of a surprise in the creation of an experience from suspense is how beliefs build expectations that make us act. As what can be seen is how expectations can become like forces and counterforces in space and time that makes someone come to an inference to buy a new shower curtain. As in the case with the “plate-leaver” one can also see how the expectations play a significant role in our learning, behaviour and emotions, and how a perceiver (in this case the “plate-leaver”) regulates the control, except from my directing of the duration of mindreading to be set to three hours.

However, if giving the question a thought about how long time you would say the “plate-leaver” spent on reasoning away from the “plate-finder”, what´s interesting is how we might come up with different approximations of time without having so much information about the reason why the “plate-leaver” stayed away. In this way, we can get a sense of how our ability of mindreading can “fill in the gaps” as to come to an inference about a length of time. So if you got a sense of how we are building a causal understanding without having so much information, you could also get an idea where a narrative constructor moves in space and time in the practice of pacing experiences and expectations.

Connecting expectations to mindreading

Hitchcock by Classic_Film Flickr

Let´s return to the man above who had an eye for expectations, surprises, and suspense and the effects they had on people´s attention and emotions. Few within science have drawn a parallel between Hitchcock´s theories about engagement and the learning and motivation theories that have mainly been directed towards education. But as we have the 7-grade model we can now explore how attention and engagement from a surprise and suspense can be understood from the perspective of pacing, which is the rhythm you give when balancing experiences and expectations.

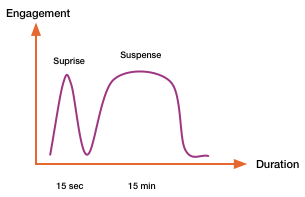

According to Hitchcock (the text can be found here), the emotional intensity of a surprise from a bomb going off at the beginning of a scene could give you fifteen seconds of engagement. If we look at the unexpected “fridge-movement”, no matter the object, we can see how it also caused about fifteen seconds of attention. The engagement from suspense by letting the audience learn and speculate about the bomb, instead of blowing it off as a surprise, from the perspective of a constructor, Hitchcock said it could give fifteen minutes of engagement.

Hichcock´s pacing of an engagement

Since the fifteen minutes of suspense are based on a structure of a dramatic story arc from a film, the example with the “plate-leaver” can give us an idea how the control of the learning can be paced differently depending on if we leave the control to be directed by the perceiver or if we, like constructors, are directing the pacing of a player´s learning.

From looking into the “plate-leaver´s” reasoning with the 7-grade model as to get an idea how a “self-regulated-pacing” of the radiator about when to return to the "plate-finder", it is easier to see how Hitchcock´s definition of fifteen minutes of reasoning, within the constraints of a movie, shows how much time Hitchcock can give the pacing of suspense. What I´m getting at, and where the 7-grade model can help us to detach media, contexts, structures, etc. is to get an idea of how surprises and suspense relate to our engagement, and how it can be understood in minutes, hours, years, and so on.

What the “plate-leavers” experience shows is how “self-directed” pacing of learning, based on expectations, shares the same cognitive mechanism of engagement as “directed-paced” suspense in a film. So if we had Hitchcock to decide the pacing of the “plate-leaver´s” mindreading, which duration from the suspense from the expectations was set to 3 hours as to get in control, Hitchcock would have to solve the 2 hours and 45 minutes decreased duration of mindreading as to make the “plate-leaver´s” process to speed up as to get in control (which could get an effect on the radiator from the stress of having Hitchcock deciding the speed of the reasoning).

Furthermore, from understanding how a surprise can be seen as fifteen seconds of engagement and where suspense, depending on who directs the learning, the experience can be everything from fifteen minutes to endless. In this way it also makes sense when we are setting a framework for an experience of the desired outcome in creation of an experience in a game why the definition of a feeling and emotion to learning, as to achieve a goal, make sense from a narrative and cognitive perspective that concerns the pacing and control - beyond structures and templates.

---

In next and third part, we will connect the control to mindreading, which will be the last part to be added to learning, engagement, and emotions, before we get to the principles of a framework that can be practiced when assuring the quality from a narrative and cognitive perspective.

I hope you´ll enjoy reading. Have a coffee or a walk, and see you when you´re ready to continue.

Katarina Gyllenbäck

Illustration by Linnea Österberg

References:

Gärdenfors, P., Lombard, M., (2017). Tracking the evolution of causal cognition in humans. In Journal of Anthropological Sciences 95. p.219-234

The links below lead to the site Narrative construction.

A short guide to the 7-grade model of reasoning.

Continue to Part 3, Narrative bridging on testing an experience – Connecting control to mindreading.

Back to Part 1, Narrative bridging on testing an experience - Distinguishing the stylistic elements.

© 2018 Katarina Gyllenbäck

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)