Part 1, Narrative bridging on testing an experience - beyond structures and templates

What it means to have a cognitive approach to the narrative and how to approach a quality assurance from a narrative perspective beyond templates and strong structures in creation of engagement in digital and interactive contexts.

The reason for the initiative to write the series "Narrative bridging on testing an experience" that consists of three parts, which can be found at Narrative construction, is due to a long engagement as an artist to forward the narrative as a cognitive process within digital media. Since my relation to science from when I studied Computer science is complicated, to say the least, due to an academic resistance to study the narrative beyond structures and templates, and where students don´t get any viable advice on how to construct narratives in games, based on a question from a student I started to write the series. Even though we might feel what science says and does have nothing to do with our daily practice in the creation of an experience in digital media, this time it does (see part 2, in particular), I share the series with the hope that we can take a collective step to move the understanding of the narrative further.

While new tech has evolved with a speed of a car race in the development of the digital media what hasn´t moved at the same pace is the narrative that has become like a grandmother that you put on a bench while visiting the amusement park. Since the question I got about how you can assure the quality of an experience from a narrative perspective came from a context where grandma is basically chained to the bench, and where the questioner is seeking an answer behind templates and strong structures from the ancestors of media, I need to get to the bottom of the view that seems to have made grandma´s legs a bit stiff, as to answer the question.

To have a perceptual and cognitive approach to the narrative doesn´t mean that you know what people are thinking. The important thing is that you know how our thinking is working to understand how our attention, expectations, and emotions connect to our learning and what motivates us to seek meaning. But since the template of the Monomyth and the three-act structure from the ancestor´s of media make us focus on the understanding of the object's behavior, their relations, intentions, and goals, inside a world, if we would like to understand the relationship between the constructor´s plotting of an experience in relation to the perceiver´s learning about the plotting, we need to get grandma off the bench.

To access the elements of learning, expectations, emotions, control, and pacing, we need to understand why grandma is sitting on the bench. Secondly, it’s important to understand what the effect is from letting her sit on the bench. Finally, it´s essential to be able to compare the differences between having grandma on the bench and allowing her to come along. So I thought the best start is to see how the testing of the narrative looks like within the context of the “grandma theory” where the question came from as to understand what it is that we need to go beyond on a more concrete level.

What it´s like to have grandma on the bench

How the template of the Monomyth (Hero´s Journey) or the three-act-structure from the film influence the assurance of the narrative is that patterns work as guides to check the differences between worlds, states of minds, character´s relations, motives, facial and verbal expressions, are clear enough on a perceptual level.

There is nothing inherently wrong in using the template from the Monomyth or the three-act structure from the film as a guide and where the narrative principles of logic, time and space are essential elements to makes sense of a world. However, where problems usually occur is when using the structures to allude to the practice of cognition-based construction of causal, spatial and temporal links that involve the perceiver´s interpretation.

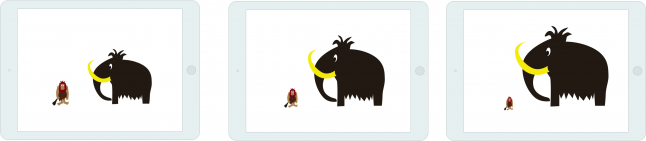

Ex. 1

What easily happens if following, for example, the Monomyth (Hero´s Journey) when creating a feeling of threat is that the focus could easily land on adjusting the appearance to look more threatening.

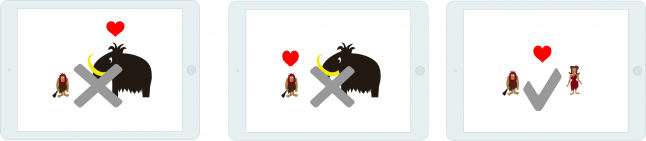

Ex. 2

Another example of how a pattern of a canonical story format influences the testing of the narrative is that the control of logic, time and space is focused on checking that the objects occur at the right place, at the right time, and directs its intentions and attention towards a correct object.

If the reliance of a consistent behavior lays on a well-tried structure of a story the cognition-based construction of causal, spatial and temporal links that tell about the perceiver´s interpretation, intentions, attention can easily become secondarily.

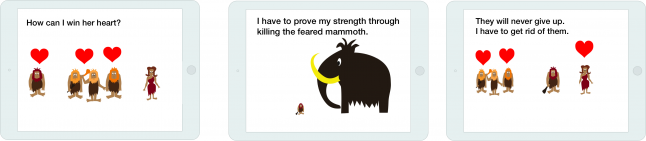

Ex. 3

As a last example, if the narrative is understood as telling a story, and there is an uncertainty from the constructor´s point of view why a perceiver acts in a certain way or doesn’t understand what to do, the assurance can easily be solved through an “exaggerated” exposition of information that tells and shows what the perceiver should think and do.

If you tell a perceiver what to think and do (unless the constructor hasn´t intentionally chosen a style and form as in the example above) a longer term of engagement can easily decrease due to the degree of the perceiver’s involvement on an emotional level, which relates to the motivating facts of learning. Why the engagement decreases are due to that we like to explore contrasts and seek meaning and act upon hypothesis and inferences about an outcome.

But what differs the constructor´s meaning-making with the perceiver´s is that the constructor needs to call upon the perceiver´s attention - not by telling or showing - but through involving the perceiver´s motivation to understand (also called curiosity). If we would say: “Don´t press that button as it will have consequences for you,” we can be pretty sure that the curiosity will increase the engagement, as well as the emotions.

It´s not an easy task to know exactly how a perceiver will interpret the smallest amount of movement and appearances that meet the goals and expectations. Intuition and experiences can help the constructor in the case of making decisions about plotting of the experience as well as the template of the Monomyth and the three-act structure. But if we would like to know how the style and form affect the perceiver´s cognitive activities, the only way to go is to release grandma from the bench, as to be able to tell how the experience is perceived on a perceptual and cognitive level.

If we decide to explore the narrative, the decision doesn´t mean that we have to throw away all the popcorns when leaving the cinema. But what we need to do first is to distinguish the stylistic elements, as it seems to be the understanding of the styles in the creation of a form that is stiffening grandma´s legs. So with the help from the thought-based method Narrative bridging, I will try to guide us through the quest to see how we can get grandma off the bench.

Getting grandma off the bench

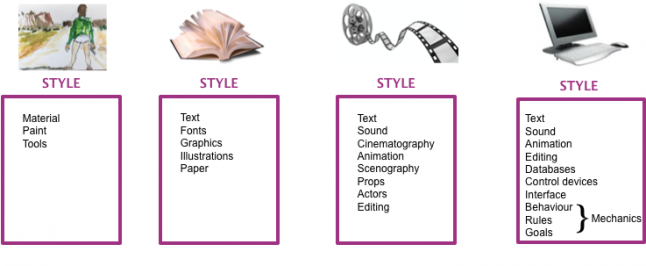

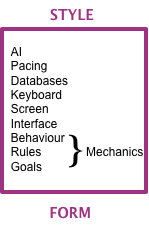

Since it´s through the style one can enhance emotions and direct attention, it´s essential from a cognitive perspective to distinguish the stylistic elements as it´s through the assisting of the style the narrative can give meaning to a form. For those who are not familiar yet with Narrative bridging the empty purple colored square below is how I use to depict the space that represents the style and form.

Before a concept gets a form, it is the stylistic element that designates the possibilities provided by the media in the construction of meaning. So the distinguishing of the stylistic elements in different media can be described as follows:

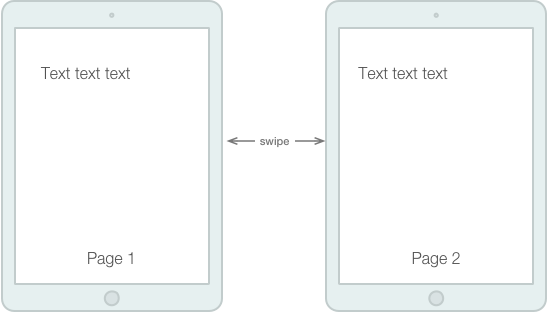

If we look at the different styles, it gets a lot easier to distinguish the elements that each medium provides in the creation of meaning. What can also be noticed is the cross-functional cooperation between the different styles and where an exchange of styles can, for example, be seen in the “swipe”-function (which is a part of a touch-screen system) and where the act of reading, and the feeling of turning a page in a book, was transferred to a digital media.

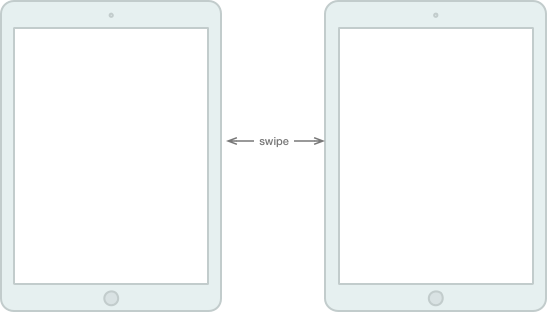

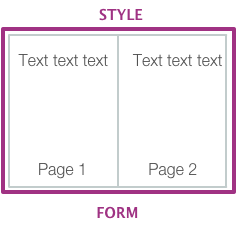

As I would like to show what happens if we think about the narrative as canonical story format in a book, it might be easier to see what the narrative as a perceptual and cognitive process does when giving the form and style meaning if we remove the pattern of the story from the book.

What happens when removing the “Text, text, text” and the numbering of the pages, is that the stylistic elements of the digital media loose meaning as to why we would like to “swipe” between two frames? As the act of “swiping” is now standing without meaning (see above) the interesting is to imagine what happens if we would like to give the swiping a meaning as not to leave it pointless. The intriguing thing is that if one holds a belief about the narrative as being a pattern of a form in a book and starts giving meaning to a new form that meets the style of an interactive media, the act is not considered to involve the narrative. From a cognitive perspective in the construction of experience, the creation of meaning becomes intuitive, which can also explain why grandma is sitting on a bench as people seek support in guides as the Monomyth and the three-act structure.

I will proceed with another example that shows how the understanding of the narrative can obscure the access to the narrative as a perceptual and cognitive process and where the example comes from the context where the question about the testing of the narrative performance has risen.

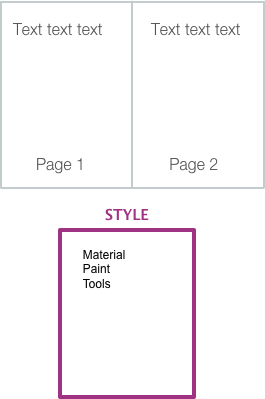

Let´s look at the stylistic elements of a painting (material, paint, tools). In a lecture held by a known profile within game research, a painting was shown that depicted the Crimean war with men in uniforms on horses (the lecture can be found here if you would like to study rhetoric). As the painting wasn´t presenting a chain of events that provided information about who the people were, where they came from, and what was going to happen, the lecturer claimed that the painting had no narrative.

If we take the narrative pattern of a form from the book, the “Text, text, text”, that was previously removed from the stylistic elements of the digital media, and try to apply the “Text, text, text” to the stylistic elements of a painting, it is not hard to understand why it´s possible to argue, as the lecturer did, that there is no narrative (and why grandmother should remain on the bench).

If one keeps moving a pattern of form as a piece in a jigsaw puzzle as to see if the piece fits a style, it is also here the opinions about the narrative appear as if it´s good or bad, fits or not, or whether the narrative is compatible with the gameplay, mechanics, etc.

However, even if the painting and its objects are not “moving” in a causal manner, event-by-event, there are two critical things one misses from a perceptual and cognitive perspective. What the painting has set in motion is the perceivers´ interpretations, imagination, and thinking in the creation of meaning. One also misses how prior experiences and expectations influence our interpretation and meaning-making. Since there are some who know that the painting is featuring the English army in the Crimean war that came to suffer a devastating defeat, and some that don´t, the experiences vary as well as the expectations. In the case with the lecture, when someone claims that there is no narrative in some media as the narrative is storytelling, if that becomes the experience of the narrative one will not expect the narrative to occur in any other contexts and spaces than them the narrative has been designated to appear in, as a storytelling.

As to show how experiences and expectations play a significant role from a narrative and cognitive perspective I will give a last example from scripting and testing of a computer-generated character (a chat-bot in the guise of a confessional booth).

As the development of the concept happened before I created Narrative bridging, it´s very amusing to use the method for the first time on this case to show what happened when I was asked, as a screenwriter, to create a character that the perceivers would enjoy talking to.

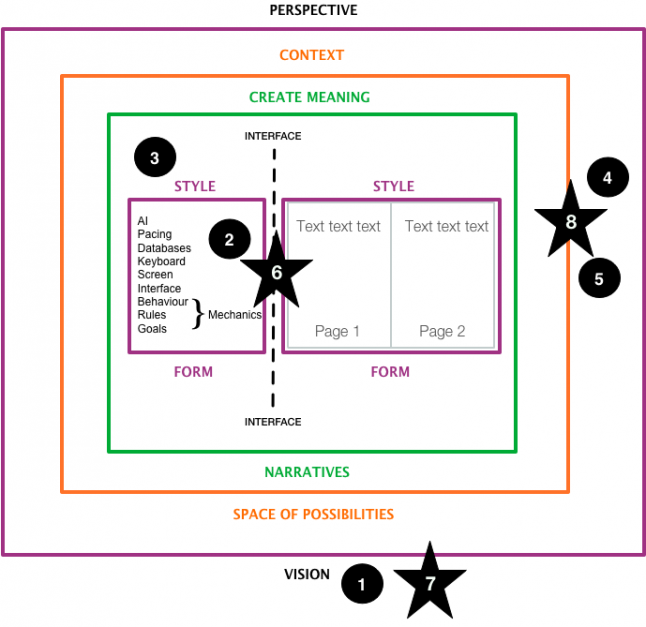

The stylistic elements that provided possibilities looked like the following:

(I have "lifted out” the AI and pacing from the mechanics as to make the elements visible).

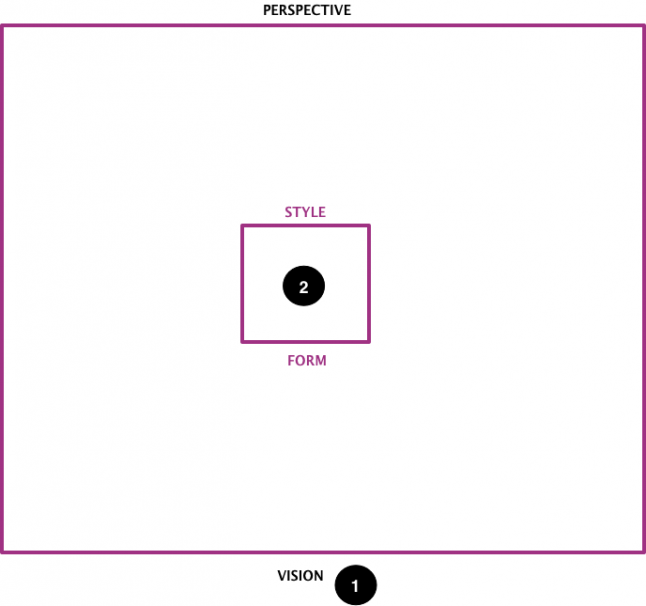

The vision in relation to the stylistic elements that should constitute the form looked like the following:

1. A character that is amusing to talk to.

2. Moods/AI

Based on the vision/goal (1), to make it amusing to talk to the character, the character was given moods/AI (2). The moods/AI were given meaning by giving the character a personality (a background, experiences, beliefs, desires, and dreams, short- and long-term goals):

3. Personality

Altogether (1, 2, 3) gave meaning to a form of a character with moods. Depending on in which direction the conversation went, if the interactor came to speak about things the character didn´t like the AI-counter for the moods went down, and vice versa. The development of the character´s moods/AI (2) was well-balanced pacing based on the character´s personality (3), which should create a curiosity to get to know the character, as to reach the desired outcome (1). But it was here an “invisible interface” occurred between the programmer and me, based on the experiences and expectations, which appeared through the stylistic elements.

The “invisible interface” was detected when I did a quality check, and the character went suddenly, and instantly, angry, happy, sad, happy, and so on. There was no way one could tell what made the character happy, sad, pleased or angry. A generous interpretation of the character´s behavior would be that it was insane, but it would not make anyone curious to find out more about the character, which would also prevent us from reaching the desired outcome (1). Basically, the only thing the character did was to confirm the low expectations people had on chatbots to be stupid and pointless.

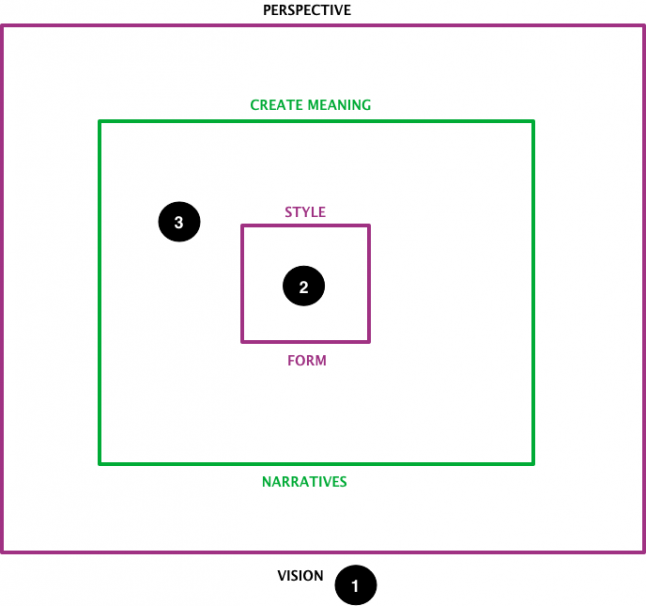

With the help of Narrative bridging, I will depict how the experience and expectation influenced the inconsistency that was found in the character´s behavior.

1. A character that is amusing to talk to.

2. Moods/AI

3. Personality

4. A screenwriter´s knowledge and experience.

5. A programmer´s knowledge and experience.

6. The vision/goal (1) is not reached due to the moods/AI (2).

From a cognitive perspective, the concept of control relates to learning. From a screenwriter´s perspective and experience (4), control refers to our expectations and emotions when we learn and understand. From a programmer´s perspective and experiences (5), the concept of control concerns a machine´s learning and behavior. So what happened when I experienced a lack of control (6) that had effects on the goal (1) the programmer didn´t have the same experience as the code, CPU, databases, etc. were running as expected. So due to the different experiences from the testing, the expectations on the goal turned out to differ as the programmer´s goal was focused on the computer´s behavior, and I focused on the characters.

What the testing revealed from a cognitive perspective was an internal “invisible interface” that occurs when experiences and expectations on the narrative performance differ and where the expectations on a story were transferred to the person who executed the narrative as being a story in a book or a film. So when the mechanic of the moods (2) was prompted, which speeded up the pacing, I was not expected to move around in this space…

…but rather here…

One could say that I became a little bit like the Spanish Inquisition that no one expects when I appeared in the “mechanic department” to explain the importance of the pacing and the AI and how it didn´t make us reach the goal (1) (if you haven´t seen Monty Python’s sketch about the Spanish Inquisition it can be found here at Youtube).

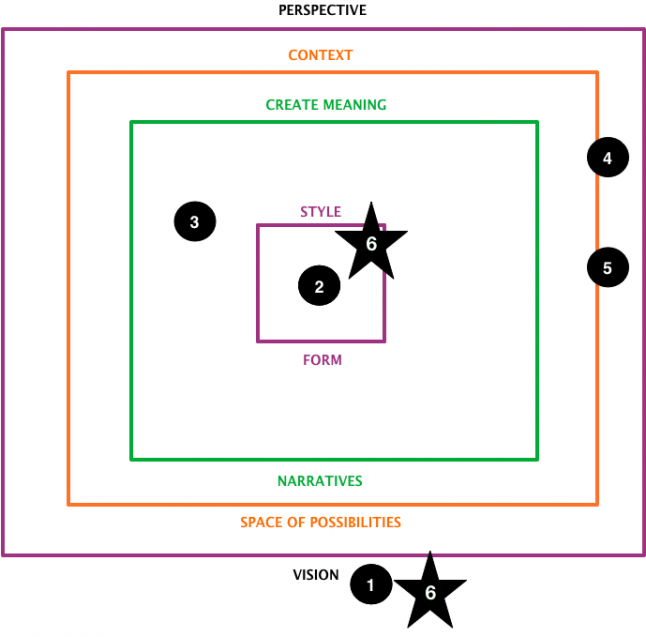

However, what can be recognized is how the jig-saw-puzzle-effect occurred, which I now refer to as the invisible interface, and where the detection of the inconsistencies (6) could be depicted as following that prevented us from reaching the vision/goal (1):

1. A character that is amusing to talk to.

2. Moods/AI.

3. Personality

4. A screenwriter´s knowledge and experience.

5. A programmer´s knowledge and experience.

6. An “Invisible interface" revealing two forms and styles that need to be merged.

7. The character is not amusing to talk to and does not reach the vision (1).

8. The team needs to share the same goal to reach the vision (1).

The inconsistencies, depicted through Narrative bridging (above), are what we would call “a call for a merging” (6) when two forms need to meet one style, as to reach the goal (1). As to adjust the inconsistencies, the screenwriter (4) and the programmer (5) had to make sense of the concept (8) by letting the character´s personality (3) show through the mechanics of moods/AI (2) in order to reach the desired outcome (7).

If having a perceptual and cognitive approach to the narrative by identifying the stylistic elements as possibilities in the creation of a form, one is already merged as a team, organizational, concept- and vision-wise. From grandma´s point of view, it is also in the invisible interface we can detach her from the bench through the decision to let the narrative assist the stylistic elements in the creation of a form by giving the elements and parts a meaning.

But most important of all, as an answer to the question, is how the distinguishing of the style is also what guides the setting of the elements in the creation of a test flow diagram as to approach a quality assurance from a narrative perspective beyond templates and strong structures.

Limbering up grandma´s legs

As I hope you have got an idea of what it means to go beyond a template and a strong structure and how experiences and expectations within a team can create invisible interfaces. By releasing the narrative, we can make it act as a collaborative tool in the creation of meaning by supporting the style to reach the goal. It also means that a person who works with narrative construction in a team is there to ensure that the narrative assists in collaboration with those who work with the stylistic elements to reach the goal.

A narrative and cognitive approach to the concept can also prevent eventual inconsistencies to occur, not only on a perceptual level by checking the object's behaviors inside a fictive world, but also on a cognition-based level as to detect contrasts in the understanding that can affect the expectations. As what caused the invisible interface in the example with the computer-generated-character was from the programmer´s point of view caused by low expectations on the performance due to experience:

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The experiences and expectations shown above can also illustrate what keeps grandma sitting on the bench. As grandma has no aspirations and can´t speak, it is simply up to us that works with the digital and interactive media do decide if we want to explore what grandma can do to the interactive media that she did to the ancestors of media. But if we decide to limber up her grandma´s legs and look at the narrative as a cognition-based construction of causal, spatial and temporal links that involve the perceiver´s interpretation, what we can find is how a negative impact from low expectations on our emotions can also be used as a positive effect on the engagement.

In the example with the computer-generated character, if we take a look at the experiences and expectations above, the interactor´s experiences and expectations on the character´s performance looked precisely the same:

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Based on the experiences that chatbots are stupid and not expected to be possible to talk to, what the narrative can do from a perceptual and cognitive perspective is to "use" the low expectation as to surprise. By giving the computer-generated character the significant abilities of being a human to have beliefs, desires and dreams (next time a so-called human-like bot is presented you can check if it´s been given an artificial ability to imagine) the temptation to “press the button” as to prove the hypothesis that chatbots are stupid became what engaged the interactors as the character surprised when not replying according to the interactor´s expectations. When reading the logs from the encounters it was amazing to see how many interactors who tried to make the character to act as expectedfrom their point of view and to see the surprises when the character did what we expected and desired it to do - amuse - which also became the gameplay.

It is also from the experiences and expectations a narrative constructor creates curiosity and suspense, as well as creating low expectations that the perceiver experiences inside a game - not from a machine learning perspective but from the control of learning about the world through the interaction with the pattern of form and style that had been given meaning to reach the desired goal. So the reason why I positioned the screenwriter (4) in Narrative bridging in the orange-colored area that depicts the space of possibilities and context is due to if we allow the narrative to become a part as an element and not a template or structure we also allow the narrative to seek/present possibilities in creation of meaning to a reciprocally shared goal.

As I intend on taking grandma for a walk in the next part of the series (which can be found here), I hope that grandma´s legs are feeling less stiff so we can take a closer look at the elements of learning, expectations, emotions, control, and pacing. Since I plan to provide a framework for how to approach a quality assurance of the narrative, you can already bring along the approach to the stylistic elements as well as the experiences and expectations that have been provided here.

If you visit the site Narrative construction for the first time and find it interesting, I recommend reading the series “Don´t show, involve” where you can see Narrative bridging used on the plotting of the online game “Journey”. In the third part of the series, you can learn more about how experiences and learning are built up through the mechanics in “Journey”. In "2 plus 2 but not 4", you can learn about how “the invisible interface” affects the creation of meaning. If you would like to see how we interpret information from a narrative, perceptual and cognitive perspective, don´t miss "Narrative patterns of thinking".

Thank you for reading!

@ 2018 Katarina Gyllenbäck

Illustrations by Emese Lukács

No animals were harmed in the making of this post.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)