Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Ori and the Will of the Wisps: Destroying Hope

A cohesive narrative is important to stories of all kinds, not just video games. Ori and the Will of the Wisps maintains this narrative cohesion for everything but one vital character.

By Shelby Carleton | @bdotexe

*Spoilers Ahead!*

Ori and the Blind Forest is, for me, one of my favorite video games of all time. What impressed me the most was the cohesion between the mechanics of the game and the beats of the narrative. You can listen to me gush over it here, if you’re interested. A cohesive narrative is important to stories of all kinds, not just video games. This involves setting up characters, environments, etc. in a context that makes sense and carries through from beginning to end. For example, it’s generally not a great idea to have a character who is afraid of water suddenly jump into the ocean without reason, explanation, build up, or warning. Of course this could happen, but there needs to be an appropriate foundation for it to make sense, and to feel earned.

Ori and the Will of the Wisps maintains narrative cohesion for everything but one vital character. And it is this out-of-place character that ruins the cohesion entirely. Before getting into why Ori and the Will of the Wisps was, narratively, such a disappointing experience, it’s important to understand what the first game built before the sequel tore it down.

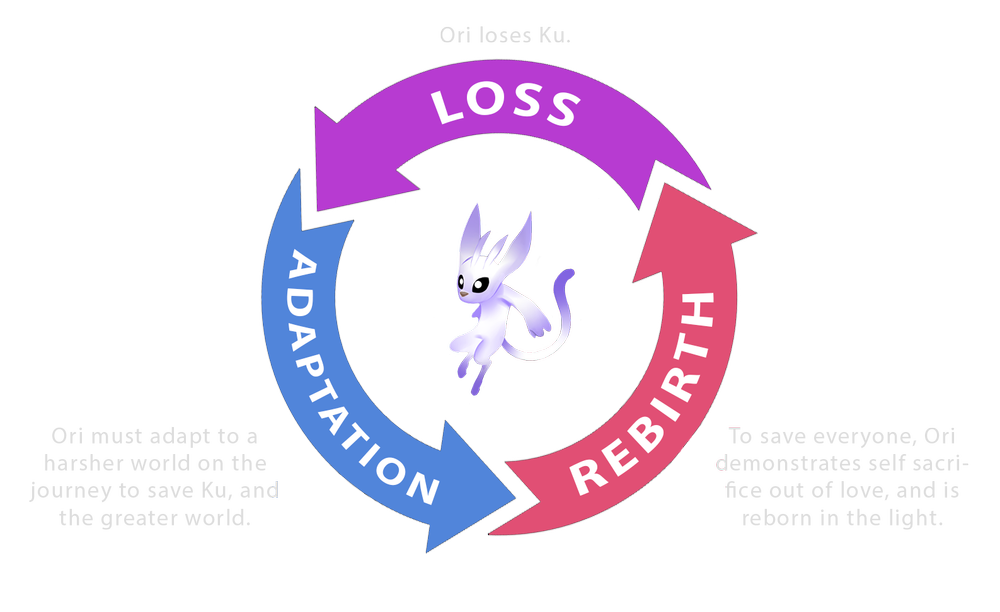

Ori and the Blind Forest maintains three important beats that resonate within the narrative and feed into the mechanics: loss, adaption, and rebirth. Ori, the main character, experiences this entire arc within the first ten minutes of the game.

Mechanically, these beats repeat themselves in the form of ancestral trees that provide Ori with the primary abilities in the game.

Secondary characters also experience these same three beats in different ways:

Arguably, the most important and hard hitting arc is Kuro’s, the primary antagonist of the game:

Including even Kuro, each and every character in Ori and the Blind Forest experienced the stationary beats of loss, adaption, and rebirth. However, it was their diverse response to that grief, and the way they found love within themselves and others even in the face of great loss, that narratively tied the game together to create a cohesive and powerful experience.

The same structure appears in Ori and the Will of the Wisps: loss, adaption, and rebirth. Once again, Ori and the secondary characters experience these same three beats in different ways:

Finally, this brings us to the most disappointing and disjointed character: Shriek, the game’s antagonist. Shriek had a difficult life. Growing up with no family, and looking a little different than the other owls, she was a complete outcast. She was taught the world hated her, and so she would hate the world. Shriek experienced a great deal of loss, and in order to adapt, she blocked out the world to survive, turning to the comfort of darkness. Both Ori and the Blind Forest and Ori and the Will of the Wisps talk of hope and love in the face of loss as all-encompassing: they are tied together to aid in overcoming grief in its many forms, to be “reborn” either figuratively or literally.

The problem is that Shriek has no rebirth.

As the game neared its end, the narrator explained, “when hope faltered, some chose to remain in darkness,” as Shriek is shown looking very broken and very sad. This created a rift in the narrative cohesion, where suddenly all talk of hope and love were thrown to the wind. I understand not every character will want to be loved. However, the game showed Shriek crawling back to the graves of her parents where she died under their wings so… clearly she wanted to be loved. The disconnect between the hope of Ori’s family, and the darkness inside of Shriek rendering her hopelessly unredeemable left a bitter taste. It made little sense based on what the first game, and part of the second game, had been building toward.

Shriek was born into a cruel world, lived a cruel life, and died a cruel death. Her narrative rings hollow in the face of the first game’s message: that all are worthy of love, that grief is experienced in different ways, that love conquers all, and forgiveness doesn’t have to be impossible. In Will of the Wisps, this remained true for almost every character. Every character, except Shriek.

When I cried at the end of Blind Forest, I wasn’t filled with sadness but empathy for the characters and their stories. I was sad for Kuro’s loss, but I also understood she died with love in her heart as she chose to sacrifice herself after seeing the bond between Ori and Naru: the same bond she had with her own children. I was filled with hope for both Kuro, and her surviving baby.

When I cried at the end of Will of the Wisps, I felt hopeless. I cried for Shriek because no one understood her. I felt she deserved the second chance, the patience, and the kindness that the narrative felt like it had been building toward. But instead, she fell to a darkness that was unnecessary, and narratively, unearned. Shriek died with fear in her heart, and took with her the hope I had so badly wanted to feel as the credits began to roll. The narrative that had been the biggest draw to the game became the biggest disappointment. And just like Shriek, I’ll die mad about it.

To hear more about story design in video games, listen to episode 19 of The Panic Mode Podcast—Story in Video Games.

This article was originally published May 22, 2020 on www.panicmode.net.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)