Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

On Incoherent Game Systems

On examination of incoherent game systems featuring Xenoblade Chronicles X, Tactics Ogre PSP and Diablo III

On Design: Icoherent Game Design

Perfunctory Introduction

In Dark Souls: It's like an NES Game! I focused on a single game and how it gave people that "NES feel." This time I'm talking about a vaguer but perhaps more common sort of feel: that a game is frustratingly incoherent.

In the Dark Souls piece I wrote "Coherent design is important - how well do design decisions work in the context of other design decisions?" This piece is an examination of design decisions that don't work when paired up with each other. That last bit is important: it's not that these are "bad designs", it's that these are designs that don't work in context - two systems work against each other, or systems encourage one style of play while content encourages another.

Xenoblade Chronicles X: It's My Party and I'll Invite Who I Want To?

Xenoblade Chronicles X is a recent open world Wii U JRPG. I'm going to simply list some of the game systems relevant to party management:

There are many standard characters to recruit and use in your party.

Your main character cannot be removed from your party.

The US release of the game includes an extra set of what were previously DLC-only characters.

To switch party members you must walk up to them in the world and talk to them. (They aren't all in the same place either)

Certain missions require certain different configurations of party members.

There is no XP sharing system - only characters in your party get XP.

Certain missions require certain "affinity" levels with other party members, which can only (mostly?) be built by including them in your party.

While characters level up traditionally by gaining XP, to power up their "Arts" and "Skills" (AKA abilities and traits) you spend a shared resource.

I ordered these purposefully - odd-numbered items are design decisions that encourage players to swap characters frequently, even-numbered items encourage players to stick with one party configuration.

This is an example of what I would call an incoherent set of systems - these design decisions work at cross purposes. As the player I can't tell if the game expects me to swap party members regularly or rarely, and neither feels ideal. If I swap regularly my shared pool of upgrade points is split inneficiently across many different members and my main character outlevels my other characters. The interface for swapping characters is cumbersome and time consuming, full of repetitive busy-work. If I don't swap characters frequently I can't do missions that require certain configurations, I don't raise affinity with unused party members, and I'm left asking what the point is of having a large number of playable characters (and extra DLC characters) if I'm not supposed to use them?

Anecdotally I've seen a lot of people express frustration with the party system - that it gets in the way of what they're trying to do, no matter what it is that they're trying to do. It doesn't accomodate any particular play style very well, nor does it allow for a greater variety of play styles.

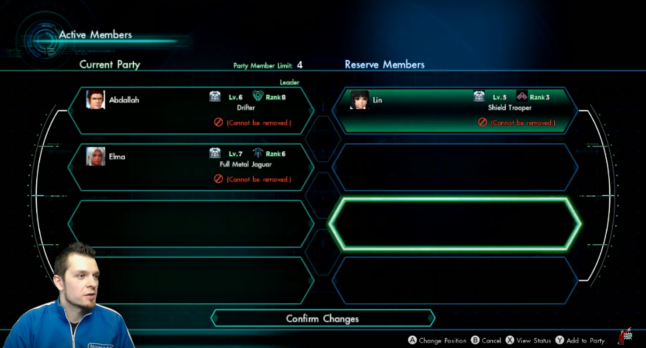

This party management screen exists, but on the right it only lists characters you're currently talking to, not all possible party members. Once a character becomes "reserve" you can't use this screen to call them back up, you have to find them in the world again. Very strange. (Note: the guy in the bottom-left is not part of the game!)

In the first Xenoblade party management is done through a simple menu that can be used to swap characters, including the main protagonist, at nearly any time. So the decision to make the main character not removable, and to require players to talk to party members to swap them, is clearly a purposeful design decision. Chronicles (the newer game) is supposed to be more of a western-style, open-world game. Having party members inhabit the world map and talking to them in physical space to swap them certainly contributes to that sense of world. In the first game, in which you could swap characters at any time, one imagines that canonically every party member is with you at all times, either watching passively as you take on enemies or also participating just out of camera frame. But in Chronicles they are canonically living their own lives - when "L" is not in your party he's minding a shop and attempting to cozy up to a recently widowed lass, and when "Murderess" is not in your party she's presumably...murdering people. Similarly in the first game while there is arguably a main character there's no "you" character - in the newer game the character you create and name is clearly meant to be "you", and making them not removable from the party reinforces this.

These are not bad design decisions by themselves. They accomplish real goals that in theory add to the game. They are, however, not such great design decisions when you have a party of four and want to take on a mission that requires swapping three of those characters out - in that case you can look forward to tapping on the Wii U game pad repeatedly to try to find / remember where those party members reside, warping to one only to realize that you're on the second floor of a structure and they are on the first, warping to a different spot, walking up to them to swap them, bemoaning that the "you" character is level 30 while they're still level 21, then repeating two more times.

Tactics Ogre PSP: Best Worst Remake

Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together for the PSP is regarded by some as one of the best remakes of all time. In many ways it is a great remake: technically flawless, attractively aesthetically remastered, and with major design changes that, according to those some, fix or improve upon the flaws of the original game. It's inarguable that the single biggest flaw of the original has been ameliorated; in the original, enemies scale to the level of your highest characters and any difference in level is devastating, which lead to mandatory player vs self training sequences to keep all character levels even. In the remake small level differences aren't as severe, so you're no longer required to spend large amounts of time in training sequences.

Sort of.

I will again describe some features of Tactics Ogre for PSP, centered around character levelling.

Individual characters don't earn XP - instead the class they belong to ("Knight", "Archer", etc) earns XP. All characters of a given class are that same, class-determined level.

Individual characters get better weapon skills with use, and also earn skill points which they can use to purchase new abilities.

The more of a certain class you have in battle the more XP that class earns. They earn no XP if not represented in battle.

Characters can only equip weapons and armor appropriate for their level.

New classes, characters and races are introduced all throughout the game, including towards the end.

The key takeaway here is this: switching to a new class puts your character back at level 1, able to equip only level 1 armor, while switching to an already leveled class puts you at that level. The game puts a large barrier to entry on trying out new classes, which only grows as you progress and the average enemy level increases.

For a more complete description of the gameplay systems and their problems I suggest Alex Lucard's Diehard Gamefan review.

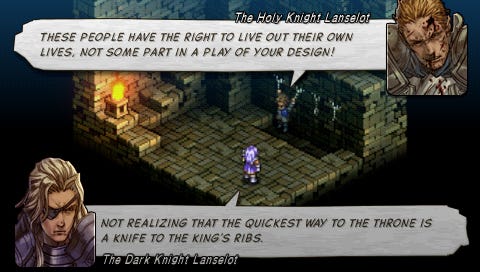

Unlike the game systems, the plot of Tactics Ogre makes perfect sense. See, there's this guy Lanselot, then this other guy also named Lanselot...

Exploring new classes is fun - clearly the developers thought so, or else they wouldn't have included them! Why then is exploring them made burdensome? When you unlock the "Thief" class the enemies are level 12 or so, and your new Thief is level 1, weilding a level 1 dagger that does 1 point of damage to enemy Golems, and wearing armor that allows them to be one-shot by bosses. So if you want to use a Thief you either hide them in the back having them do nothing for multiple fights while they level up, gimping your entire party, or you travel the world map looking for easy random encounters they can participate in.

The "upside" of this system is that if you get a new character and want to switch them to an existing class they start at a high level. But even that has barriers - characters earn skill points and weapon proficiency over time, so while you can put a new character into an existing class they won't have the same skills and weapon profiency as older characters.

So many different character classes to not use. There are nine types of dragons! Nine! And to use each one you have to start them at level 1, even if you get them in the last 10% of the game.

In the original Tactics Ogre when characters die they die for good. So perhaps the justification for this strange class-based leveling system is to mitigate that: now if a character dies you can hire a new character to replace them at the same level, rather than having to level them from scratch. But the remake has multiple other changes to prevent this from being a realistic scenario: when characters die you have a chance to revive them, and if you don't revive them they lose just one of three lives. Similar to a modern racing game's rewind feature in the PSP remake you can rewind moves if something goes wrong, to prevent a character from dying in the first place, or to revive them in time. So the one use case the class-based levelling system seems most applicable to - existing characters dying and needing replacement - is rendered moot by other game system changes that make permanently losing a character extremely rare.

As is often the case with these incoherent systems they feel (whether this is truly the case or not) that they were designed in isolation then just didn't fit together quite right. Characters having multiple lives is a fine idea. Being able to rewind moves is a fine idea. Making it easy to replace dead characters is also a fine idea. But these things together are largely redundant, and while they make a now-rare case less painful (replacing dead characters) they make the now more common case (just wanting to try out a new class with an old or new character) much more painful.

Just to make it perfectly clear why I'm calling this incoherent: on one hand multiple redundant death-prevention systems exist, while on the other hand the levelling system seems designed with the assumption that death is common. Similarly the content design suggests to players that they should be acquiring and using new classes throughout the game, while the levelling system encourages players to quickly identify and stick with a few core, early-game classes.

Diablo III

I wasn't sure whether or not to include Diablo III, because unlike in the other cases the issue with launch Diablo III was less a set of decisions working against a different set of decisions and more one very poor decision working against the fundamental appeal of the game. However I'm including it, because it kind of fits and it's probably good to dicuss a game more than a handful of people are familiar with.

Diablo has always been a game about collecting loot. More specifically, collecting randomish loot rewards at randomish intervals in a way that is incredibly psychologically satisfying.

Diablo III introduced an MMO-style auction house. (We won't even get into the real-money auction house!) The purpose of an auction house is to allow for a currency-based economy rather than no economy or a clunky, unreliable, barter-based one. With the auction house you can easily convert items into gold and back.

This breaks the game.

With the introduction of the auction house and the ability to easily convert items into gold all loot drops effectively become gold drops, and all loot runs become runs for a certain expected value of gold. In the early days of Diablo III players would find the highest EV runs and run them over and over - why not? The fact that one run drops "Sword of Ice + 5" and one drops "Shield of Magic Reflectance" is irrelevant when one can be converted to currency and then to the other.

Not only is a random reward schedule psychologically sweet but it can also entice players to try equipment and play styles they wouldn't otherwise have considered, keeping the experience fresh and encouraging them to have more fun they would playing perfectly planned builds.(This is the theory behind why in new X-Com you don't choose character classes) With the addition of the auction house new equipment is less likely to tempt players into trying out new play styles, as they can simply trade that equipment in.

Presented without comment.

Auction houses work fine in MMOs but MMOs are already fundamentally currency-based games: players spend large amounts of time to earn some sort of weird in-game currency they use to enter raids, then earn "DKP" (don't ask) for participating in those raids, which they then spend on drops. The particulars of those drops do matter, of course, but multiple currencies are already in play, and earning end-game items is ultimately about expected value and "earning" those items rather than getting them at random. For some subset of players previous Diablo games worked like that as well - they traded in-game or on shady websites and did runs in vast enough quantities that gaining items was effectively earning them as a wage slave. But for many players the Diablo experience was just you play through the game and use cool new items as you get them. For those players the addition of the auction house radically changed the game for the worse.

There's a strong theoretical argument against switching from an item-based to a currency-based economy. But there's also a purely experience-based, empirical argument as well: Earth Defense Force: Insect Armageddon was released a year before Diablo III, also switched from a loot-based game to a currency-based one, and exhibited the same problems. This is from the IGN review of that game:

The only downside to it, though, is that most weapons in the game are now unlocked with experience rather than through random item drops. Yes, there are some random items in Insect Armageddon, but a big part of the last game's appeal to me was the excitement I got at finding random loot. It's still here, just greatly depreciated.

Though the systems are not identical this blurb applies almost verbatim to Diablo III.

Once again, to make it perfectly clear what exactly I'm calling incoherent here: the fundamental appeal of Diablo has always been random loot, and that's clearly supposed to be a major draw of Diablo III as well, but the addition of the auction house made the specifics of the loot dropped irrelevant compared to its converted currency value. On the surface level the game was still very much about dropped loot, but on a systems level dropped loot didn't actually matter. As a thought experiment, how different would the game have been had the only drops been gold, and the auction house stocked by enterprising NPCs? My answer is "not very" - which is to say that the auction house effectively removed the single most core and appealing feature of the game.

Concluding Remarks

I didn't try to strictly define what incoherent design is, nor do I see the point in doing so, but it's worth observing that some purposeful tension in design is not the same as incoherence. On another note, a related cousin of incoherent design is the common "the optimal way to play is the least fun" affliction - often this is not the result of competing systems or content, but rather systems that simply don't engender a fun experience when used optimally.(Admittedly this is a blurry line) And while I'm not a fan of simply declaring that something is a "bad design", of course there are designs that simply don't work.

In the three games highlighted the designs do work, at least in the abstract. Auction houses are common in games and often a fine idea. Swapping party members via conversations at in-game locations could be reasonable, for example in a game in which swapping characters was supposed to represent an infrequent major decision. Levelling character classes rather than individual characters could work in a game designed from the ground up to put that novel concept to use, rather than being bolted onto a remake that originally used a more traditional system. But in these three games these designs don't work well when paired up with the systems and content that surround them.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)