Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Narrative Negative Space in Games

I have questions about how narrative and negative space work in games, so I try to attempt to answer them, to myself.

Originally posted on:

eventnode.tumblr.com/post/121171665082/narrative-negative-space-in-games

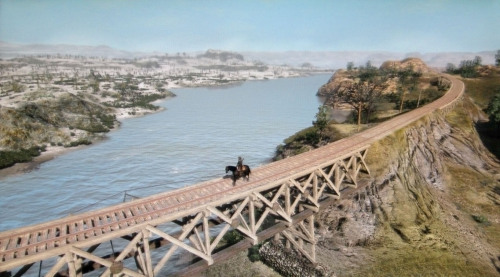

Heads up, there are some Red Dead spoilers.

Oh hi there!

Hey

I just came by this link looking for some Zima. Do you have any?

Uh no. This isn’t 1998. I think you’d have better luck going to a Angelfire or Geocities website.

Oh okay so what IS this about?

Well I’m talking about how effective negative space can be when used in some games, especially when it comes to narrative.

WHAT ISSSSSSSSSS negative space?

Well in, terms of traditional art, it’s the “blank space” or areas that aren’t the direct focus of a piece. It’s the dark room where only a beam of light shines through. It’s the arrow you don’t ever notice that’s between the EX in FedEx.

Oh god! You’re right about the arrow. Now I’m never going to able to unsee that. But how does that have to do with telling a stories?

Well, that concept can also be applied to developing deeper characters, build tension, form relationships, or create a seed of information that will later pay off. It’s a very powerful tool to use and almost any story worth its salt uses it. Otherwise you’d just have story that hits plot points (this happened, and then this and then the end.)

So a reoccurring thing is that negative space allows you to breath a bit?

Absolutely! In a story it lengthens a story out and, when done right, can add depth to your story as well as anticipation for the next big point. Take, let’s say, the first Terminator movie.

Why are they even making another one?

Cause that’s the thing to do now a days, I guess. Run old things into the ground. Anyways, the movie is primarily two characters being chased. It’s a formula a lot of other movies use. But what the original does so well is breaks to A. Build tension/anticipation for the next big scene and B. Develop the characters and their relationship to a points that you like/root for them and that when they have sex and get all lovey, it feels natural.

It does do that pretty well doesn’t it? And it didn’t need Cameron 3 and a half hours to tell it either! But I’m assuming you’re going to get into how this works in games?

Yeah. Why do you say that?

Because that’s all you ever seem to talk about on Twitter these days. That and Splatoon. Also, it’s the title of the article.

Right. I mean you can take either the narrative or visual arts approach to negative space in games. Now how you use it all depends on what type of game you’re making.

How so?

Well, let’s say you’re making a linear game. You can frame an environment or focus to the exact composition you want because you know the player will always see it that way. While in an open world, you’d have to take the approach of broader strokes in an environment to get a point across.

Can I get an example?

Sure. Let’s say there’s a castle and the surrounding area on fire. In the linear approach you could frame it up to show the castle exactly how you want and what parts. In open or non-linear you’d have to burn the surround area as you approach the castle, to effectively tell the player. You wouldn’t even need bad Blade Runner-esque voice over to rely that info. The player would get it.

Cool. How about narrative than? I can see how that works in a linear game. But what about non-linear?

Yeah this is where it can be fun. More so because you can see it in more and more games, like The Witcher 3 or Skyrim. Player choice, or player agency, becomes the focus. All these other approaches to negative space are creative intent. Unlike any other medium, games have recently been knocked on for being too linear or too guided of an experience. Why? Because, for a lot of people, the most meaningful and lasting choices come from just being in those spaces and seeing how things react to what you do. And most of those come from non-scripted events. They come from the space between side and story missions, the negative space.

You’re right I guess. I like doing story missions, but the things I tend to remember the most are scenarios like hog tying people to train tracks and waiting for the payoff.

Uh sure.

But still, that doesn’t explain your title: Narrative.

It does in some ways but I’ll go more in-depth. I have a strong belief that the player can, when encouraged to, create and embrace a variation of the character they are playing. This is partially on the player to ask “who is this person I’m playing outside of the missions and dialogue they’re actually speaking? What actions would I find compelling for them to take or not take?”

But it’s really on the designers to allow for that to naturally grow and be encouraged. John Marston of Red Dead is a perfect example of this.

I loved John! Father of the year…I think? Wait…can you give me a quick reminder? It’s been like forever since I played that game.

Marston is a former ruthless outlaw and a killer, but when you start the game out he comes off as desperately wanting to put that past behind him and just live out his days quietly with his wife and son. However, he is forced back into his old ways to hunt down his old companions. This set up is so exciting as a player. You can decide on your own which path is more compelling for you.

The game doesn’t push you in either direction in it’s scripted missions or cut scenes. By the end of the game you could return to your family in a number of ways. Either a man who has kept to his straight and narrow path, or a man who is ran by his vices. Either way, your family will not know, but you as the player will.

OHHHHHHH! Now I get it. That’s something I hadn’t thought of but in retrospect I definitely played him like that in the back of my mind.

Yeah I was in the same boat. In the end though, it shows the power of giving the player just enough info about the character you are playing as to run with a multitude of character arc possibilities, but not enough to hinder that idea of who you want to play as. Being an empty chell (GET IT) of a character, or voiceless protagonist isn’t compelling. While a fully formed character can be good with strong writing it doesn’t leave room for interpretation and can lead to ludonarrative dissonance,

Dude, what was that word you just used? Ludo what?

Just google it.

In the end it doesn’t always work for everyone (that shouldn’t be your goal anyways), but it does work for the right audience. Some people just dont care about stories in games and just use the game as entertainment. Blow shit up.

You mean like the people who don’t like Boyhood? I don’t associate with people like that.

Word.

Well this was a good chat. Thank you

Sure. Anytime!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)