LEVY: Designing for Accessibility_05

My name is Dan St. Germain and while in undergrad, I worked with four other students on creating a blind/deaf accessible video game called LEVY. These blog posts will be dedicated to explaining the different UI, UX, and design decisions that were made.

Disclaimer: When the term accessibility is mentioned in these blogs, it is primarily referring to blind and/or deaf accessibility. Games in their modern form are highly audio/visual experiences and we hope to discuss how to approach the task of making modern games more available to a larger and more varied audience.

LEVY: Designing for Accessibility_05

05: Setting the Scene

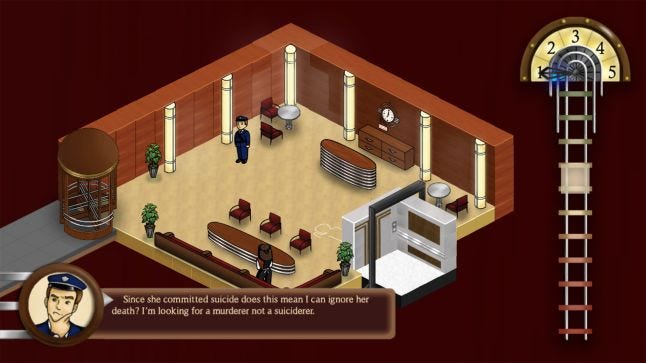

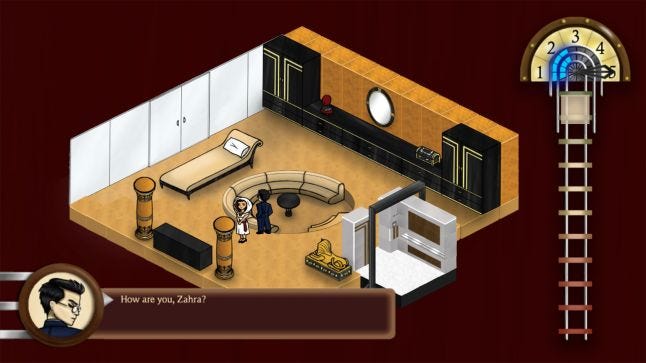

As mentioned in previous blogs, an incredibly important part of LEVY’s design was establishing a consistent system of informing the player about what was on screen. That goes hand in hand with keeping the screen itself consistent and following a pattern. Or, to be less pedantic, we made sure that each area/room was the same shape and followed a grid so when it was described we could repeat the same grid-like order for each floor too. We ended up using an intuitive, yet simple, left-to-right style of describing. But the process does not need to be complex. Better to be simple and understandable than to be overly complex and give more information than is necessary.

Like with so many things throughout the LEVY project, the audio had to match the visuals. It was important to make sure that the visuals were not too complicated nor took up too much room on screen at any given time. Too much detail and the scene would take minutes to fully describe. The simplistic rooms, in conjunction with a streamlined description pattern, make each room take less than a minute to fully describe. Again, this is akin to the idea that each room takes far less than a minute to take in visually. Fill the rooms with too much furniture, clutter, and detail and in order to make an equivalent audio experience, we would need to have much longer descriptions. Conversely, if they’re made too sparse then any changes become glaringly obvious on both accounts.

Past the room layout, the screen experience also had to be laid out in a comprehensive way. For the most part, the screen space is divided into sections with very little overlap. The main gameplay section with all the floors and the elevator take up the largest central section. Below that is the overlapping space for dialog boxes, but it is not so big as to take up the screen. An entire floor can still be viewed while the dialog box is present. Then, off to the side in its very own space is the primary UI element. It never overlaps the main gameplay section and never has a background change. The UI element itself changes, of course, from gameplay, but the environment it is in is completely static. Even the options menu primarily takes up hitherto negative space, still leaving room for the dialog box and UI element to be visible when the game has been paused. Each major player on screen has its own designated zone and this helps keep the information easily distinguishable and therefore more easily describable.

A concept that has not been discussed much in this blog is impartiality of description. It is an important and vast topic mostly outside the realm of LEVY, but I would be remiss to not mention a portion of it here. Earlier in this blog I talk about the importance of having audio match visuals in gameplay. LEVY is full of art-deco, 1930’s, and Chicago inspired visuals, but the audio describers are both very obviously modern individuals. It is important to know that that is okay. It is more important for the content of the audio and visuals to match more than the style to match. Having audio describers with thick 1930’s Chicago dialects would undoubtedly deepen the experience, but potentially at the cost of players not being able to understand any of the audio information that is much more important for them to receive. (Full disclosure we do have an over-the-top style describer voice for the newspapers simply for comedic effect.) Additionally, if the deeper audio experience is tied to the audio description, then the players who use it or need it are getting a richer experience than those not using audio description. Audio description is a tool meant to create equity among audiences, not a tool to differentiate two separate experiences.

At the end of the day the audio describers are there to open the game to more players. Each piece of the game both visually and audibly are there to do the same thing; organized in a way to best create an equal experience for anyone who wants to play the game.

LEVY, at the time of writing, is in a public beta state. It is available for free to download and play from https://razzledazzlegames.wixsite.com/levy Thanks for the support!

Designing for Accessibility_01: https://ubm.io/2KxfLKf

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)