LEVY: Designing for Accessibility_04

My name is Dan St. Germain and while in undergrad, I worked with four other students on creating a blind/deaf accessible video game called LEVY. These blog posts will be dedicated to explaining the different UI, UX, and design decisions that were made.

Disclaimer: When the term accessibility is mentioned in these blogs, it is primarily referring to blind and/or deaf accessibility. Games in their modern form are highly audio/visual experiences and we hope to discuss how to approach the task of making modern games more available to a larger and more varied audience.

LEVY: Designing for Accessibility_04

04: Conveying Information

There’s a lot of info that players need to know while playing a game. LEVY handles the delivery of that information through three major methods: an audio describer, sound effects, and a dialogue describer.

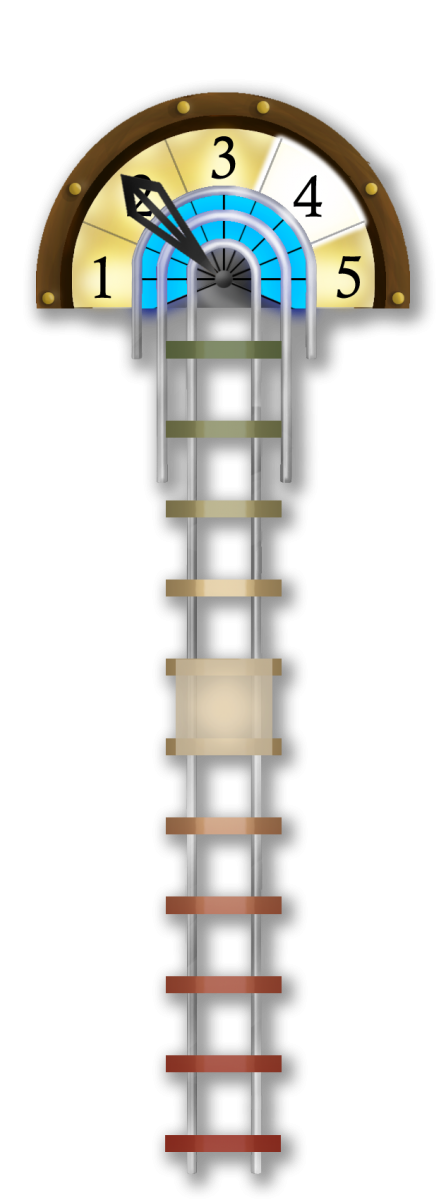

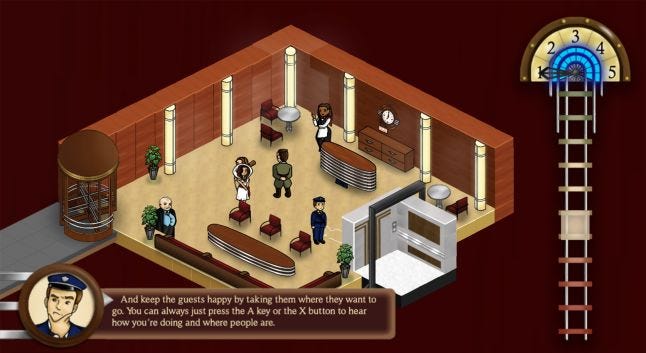

The audio describer is responsible for much of what these blogs have already talked about; describing floor information, what characters look like, and the user interface information. LEVY, like many games, includes a UI overlay during gameplay. This element shows the player how much energy they have left before the day is over, what floor they are on, what floor a character is calling them from, and their satisfaction rating with the hotel. One challenge during the production of LEVY was making sure that the UI element would make sense and be consistent both visually and audibly. Thus, the entire UI element has an elevator-type theme to it with a half-circle energy meter and floor indicator which highlights for when and where the elevator is called, and a vertical satisfaction meter that resembles an elevator shaft. With that decision, it partially merges the roles of sound effects and audio describer for the UI information. There is a sound to represent the energy depleting and a sound effect for the elevator being called from a certain floor. In certain cases, the audio describer will then join in specifying the general information given by the UI element, i.e. if someone is calling the elevator on floor 3, the player will hear a *ding* accompanied by the audio describer saying “Floor 3” for the sighted player, the “Floor 3” is replaced with seeing the indicator for Floor 3 light up on the primary UI element. Now you may be thinking that a sighted player could always see the UI, wouldn’t trying to equalize those experiences be overwhelming? But not necessarily. An advantage of having a game set at the pace of the player is that they can check the UI whenever they want to or need to. For the sighted player that just means glancing over to the side. For the blind player, we have a button with the exclusive function of giving a top-down readout of the status of all UI information. What’s important is ensuring access to all the same information and making sure that access is just as easy and streamlined for a blind player as it is for a sighted player.

Sound effects also play a role outside of the UI however. It was important to remember that all visual information needed an audio counterpart. One problem that occurred early in testing was that blind players would not be able to discern where the different floors were and thus could not know where and when they needed to stop moving the elevator in order to open the doors and drop people off or even pick them up. To address this, the audio describer announces the upcoming floor when the player is moving up or down and the player can hear the sound of grinding metal when they are in the area that they can open their door. This sound balances out the information being given by sight and by sound. Additionally, the elevator’s speed slows when it is near a floor to allow finer control and prevent players from flying past where they need to be or may want to look (or listen) for clues.

The dialogue describer is one of the final ways we convey information through audio. While not necessarily professional voice acting, this audio describer’s role was to speak every line of dialogue between characters or any other written information that was not a part of the environment, using different inflections for different characters akin to the narration of an audio book. For example, using a slightly higher pitch and faster cadence for a female, or a slower more rhythmic pattern of speaking for an older man. During conversations between people, the audio describer would say the name of who is speaking the first time they speak, but after that, the different patterns of speech indicate which character is currently speaking in the conversation. After each line of dialogue is complete, a small, unobtrusive sound is played. The player must press a button to continue the game, and this added sound is an indicator to the visually impaired to move on.

The purpose of having the audio and dialogue describers being two different people is to help distinguish what is “Game information” vs. “In-game information,” respectively. Hearing two characters speak to each other and then hearing a room described all with the same speaker and tone lends itself to potentially confuse an audience or even overwhelm them. All the different types of audio needed to work together in order to deliver all the information to the blind the player that the sighted players have innately. That said, several of the featured audio mentioned here is beneficial for all audiences to have, sighted or not. It’s important to remember that by raising different groups to the same level of play, it can result in a better experience for all of them.

LEVY, at the time of writing, is in a public beta state. It is available for free to download and play from https://razzledazzlegames.wixsite.com/levy Thanks for the support!

Designing for Accessibility_01: https://ubm.io/2KxfLKf

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)