LEVY: Designing for Accessibility_02

My name is Dan St. Germain and while in undergrad, I worked with four other students on creating a blind/deaf accessible video game called LEVY. These blog posts will be dedicated to explaining the different UI, UX, and design decisions that were made.

Disclaimer: When the term accessibility is mentioned in these blogs, it is primarily referring to blind and/or deaf accessibility. Games in their modern form are highly audio/visual experiences and we hope to discuss how to approach the task of making modern games more available to a larger and more varied audience.

LEVY: Designing for Accessibility_02

02: Finding a Solution

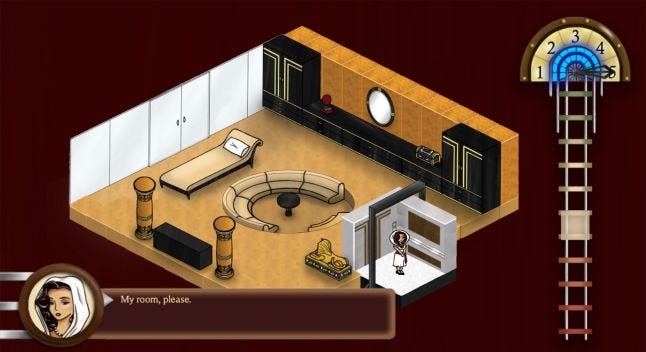

Unfortunately, I can’t even say with confidence that what our team did to make LEVY accessible would even work for every other game – not even most other games. We chose to go all-in on audio description – a tool currently used in static media like film and television wherein everything on screen is described by a non-character narrator. We had every character, room, and item described so that even if you couldn’t see the environment, you knew what was going on. Audio description can work in games if there are relatively simple or just few mechanics, especially if the player has no sort of time limit on their actions within the game. If there is important information on screen that the player controls the output of, like turning a camera or selecting a room to look at, it can be described at that pace. If there are things happening in the background that the player is just looking at, like a cutscene or being locked in a conversation with an NPC, it can be described not unlike a movie. For most games that are – for lack of a better term – in “real time,” however, audio description is daunting at best and infeasible at worst. If you try to put those above two situations together, with changing information and a camera that the player controls at the same time, you run into issues with using static audio description especially if that is the only accessibility feature that has been implemented for vision impaired players.

Even calculations-based games can suffer from this. Imagine trying to describe all the relevant information for placing a single piece in Tetris. Translating that into real time description for every piece creates a new set of issues. As such, when making LEVY, the biggest challenge was ensuring that the game was designed in a way that was audio describable. In order to do that, we took some pointers from audio described film and television and decided to have the floors visually distinct from each other, but always laid out and described in uniform ways, as well as a uniform pattern of description throughout the game so players could better notice when something new appeared or something familiar was missing. Characters’ appearances are only described once when first encountered since they never change outfits. Instead of describing things such as “the elevator doors open” we have the sound of mechanical doors opening, an audio format for telling the player where guests are and where they want to go, and fully audio recorded dialog, just to name a few features. At the end of the day, the game itself was also designed to be very straightforward, requiring functionality on only a few buttons, so that the game was audio describable around its intentionally simplistic mechanics.

As mentioned earlier, audio description is not for every game, but almost every game has room for more accessibility. Playing the game with sound off can help highlight areas where visual cues are needed or where the players might have to rely too much on slight sounds to determine character positions, amount of a resource, etc. A lot of these more minor accessibility features can be implemented in just the UI elements of the game. In later blog posts, I’ll talk more about how the UI on screen can work to make games more accessible.

LEVY, at the time of writing, is in a public beta state. It is available for free to download and play from https://razzledazzlegames.wixsite.com/levy Thanks for the support!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)