Lenses And A Little Bird: "Bioshock Infinite" As A Story

I discuss the narrative of "Bioshock Infinite" from six viewpoints based on the simple question: what is it really about? What emerged was a surprising discovery about the story's protagonist.

Bioshock Infinite | Irrational Games | 2K Games

Bioshock Infinite | Irrational Games | 2K Games

As I stared through the rippling surface of baptismal waters, seeing three familiar faces and reeling from a mind-bending finale, I recall a trip to an optician. It wasn't an extraordinary trip; I simply tried lens after lens until I found the ones that helped my vision regain clarity.

Bioshock Infinite had me feeling that way throughout. With all the plotlines weaving in and out of each other, I changed lenses through which to look at the game almost as often as I switched guns and Vigors. Ken Levine and the Irrational team support open interpretations of their work; they've inspired just that. And I've realized something: when we ponder a work's meaning and the answer eludes us, the meaning often lies in the asking.

So for this 'week', I ask the question: what is Bioshock Infinite about?

Spoilers abound.

1) "BIOSHOCK INFINITE IS ABOUT ERASING A DEBT."

The premise features prominently in the opening scenes, and Irrational gives weight to it through a series of rather sophisticated environmental cues. Booker DeWitt's box, handed to him by "A Lady", tells you so much not despite its few contents but because of them. A gun. A photo. A key. This is everything the man is about now: the mission. (Interesting parallel: sword, scroll, key.) The storm also sets the perilous atmosphere in which two terse messages and a dead guardsman deliver a not-so-subtle incentive. And there's no cutscene in sight.

Minor note: the guardsman business was a mystery to me for a time. If there had been some red smudge or small blood spatter on the sheet of paper with the lighthouse combination, it would have been a bit clearer that he was tortured for that sequence. It wouldn't lessen the threat of this 'Us' either, but sharpen it. The message moves from "we killed a man and put him here to frighten you" to "we will stop at nothing."

But Booker's motivation (and ours) shifts away from the debt as we grow to care about Elizabeth and it soon loses importance. Even if we were to consider the penance he owes his daughter as a form of debt, that doesn't come into play until the very end. Further, a story about erasing debt doesn't warrant a multiverse. Irrational's devs wouldn't be so... well, irrational. So this lens doesn't work.

2) "BIOSHOCK INFINITE IS ABOUT A MAN NAMED BOOKER DEWITT."

As a character study of our roguish protagonist, the game fares only a little better. We never really know enough about him. Cornelius Slate's arc at Comstock's propaganda exhibit was a strange yet wonderful way to reveal Booker's backstory at Wounded Knee, but it's a short sliver of thread that we don't pull at again until the ending. For a first-person game, players are decidedly shut out of the avatar's mind. Of course, it fits his character and trans-dimensional circumstances. And the Booker-Comstock divide brings a grounded and fascinating perspective on pivotal choices.

The best character moment for Booker is the guitar scene, I'd argue, which somehow eluded two of my playthroughs. How rare a revelation is it to find that one of our tough, gruff heroes, for whom a gun is his arm's extension, learned an acoustic instrument in his youth? Too rare. A damn beautiful moment that certainly isn't the only one, but this and its kind are in jarring contrast to the bulk of the game's blood-drenched narrative.

While identity isn't something that aligns between player and avatar, behavior matches up alarmingly well. I remember a distinct feeling of pettiness after the Welcome Center, where shiny objects wrenched my attention like a child and a history of playing games primed my inner kleptomaniac. The "honor system" food store? Fantastic moment of epiphany. Fifteen minutes in and devs had molded me into Booker.

There's another trait of Booker's which we witness and enact. Only this one gets all the attention.

3) "BIOSHOCK INFINITE IS ABOUT THE NATURE OF VIOLENCE."

Yes, sky-hook executions and exploding heads and disintegrating bodies are graphic. I don't need to go into it. But as I'm sure someone's mentioned, Booker has a habit of excessive violence starting back from his teenage years. It fits the narrative. The bigger problem, I think, is that Infinite fails to even acknowledge Booker's actions as being excessively violent, let alone make a statement about it.

Consider the game's first display of violence: two policemen, in the middle of a crowd of civilians, decide to rip into a man's skull with a spinning saw of magnetized hooks. Either the lapse in judgment would have lead to a PR nightmare, or this is a world where folks revel in brutality like they admire sunsets. That Booker usurps the act is irrelevant; idyllic Columbia proves as bloodthirsty as the False Shepherd himself. Because no one reacts to brutality, Infinite seems to say that it's just business as usual. And that's way too simplistic -- especially for Irrational.

Even Elizabeth is guilty of obliviousness when she sees Booker kill for the first time. Whether shot once in the head or burned alive or ravaged by man-eating crows or sky-hooked in the neck, she's soon okay with it. I read that earlier designs had Elizabeth's tear abilities metered to her state of mind; in addition to more audible disgust, Liz could have also shown fatigue or agitation when Booker kills too viciously. It would create tension in gameplay to match the nature of Booker and Liz's relationship as two strangers with so little in common.

Or, yes, the game could have also not relied so heavily on combat gameplay. Maybe. At the very least, you'd need a very different protagonist and therefore a very different story for that. It'd be a completely different game.

4) "BIOSHOCK INFINITE IS ABOUT A WAR WITH THE VOX POPULI."

It's established that one of the game's central themes is the high price of undoing the past. Since the plot dedicates much of its second act to Booker's quest of arming Daisy Fitzroy's militia, who should we fight in the last battle but the Vox Populi themselves? I was disappointed at first, fighting what had seemed to be the penultimate foe. But between the epic bullet-storm and taking a moment to consider it all, devs' choice here suits the story well.

On Elizabeth's power of tears: Chen Lin's arc is where it started to unravel for me. Is Liz opening doorways through which she and Booker travel to other dimensions? Or is she ripping through the space-time fabric to merge a different reality with her own? The former is what the dialogue indicates but the latter is what happens in actuality. Only this can explain how Booker could reasonably expect to have a deal with Daisy after opening the tear. He's pasting in a few new pages, not opening a whole new book.

However, this lens only just accounts for a multiverse narrative and doesn't justify making Booker and Comstock the same person. Viewed in this lens, the game involves too many superfluous elements. The Vox Populi are, after all, an element of something else.

5) "BIOSHOCK INFINITE IS ABOUT THE CITY OF COLUMBIA AND PRESIDENT COMSTOCK."

We can dismiss this lens quickly not because the world has shoddy construction. Quite the opposite, Irrational devs again demonstrate their worldbuilding ability to fantastic effect. Alternate histories have it a bit harder than fantasy or sci-fi because there's less of an expansive list of tropes on which to rely. They have to explain every liberty they're taking. Yet none of it felt forced, thick, or heavy-handed. And we understand how Comstock's ideals of religion, fundamentalism, American exceptionalism, and so on, have shaped the airborne city-state.

That said, let's begin the nit-picking.

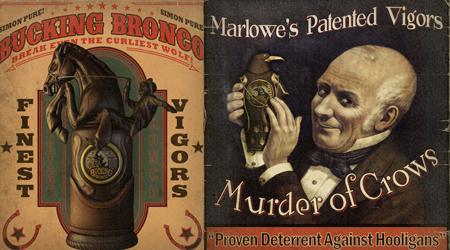

Vigors, we've come to understand, are this installment's answer to Plasmids. They're crucial to combat and they even get a little screen time in the story. But no other world element receives less integration than vigors. Songbird gets a few chalkboards of drawings and a full Voxophone, but vigors are all but left to the inductive leap. Why are they so widespread yet underused? Why did Comstock see fit to allow their existence?

I decided to improvise a bit. Here's something I came up with on the fly:

Since Vigors are marketed as items of convenience ("light the way," "deterrent against hooligans," etc.), they shouldn't grant such devastating and permanent powers. Bottles should be much smaller, to be consumed in very small doses for temporary effects, like we ingest cough syrup. A voxophone could explain that overdoses lead 9/10 times to death, with the odd 1/10 leading to permanent deformities: Ravenmen, Firemen, etc. Also, Devil's Kiss should be a flashlight, not a grenade, and no commercial product should have the word 'murder' in its name. (Because isn't that a sin or whatever?)

Consuming multiple vigors can lead to excruciating death even in safe doses due to "unfavorable chemical reactions with the immune system", referencing why folks only have one ability. How can Booker survive overdosing on 8 vigors? This could be an effect of crossing dimensions on the body's immune system. Most of the consequences of transdimensional travel seem to be negative; why not have a positive?

Also, as is pointed out in this rather humorous summary, why also do people share some of their innermost thoughts on voxophone and then leave them lying around? It shouldn't have been an issue in the first place, considering that the Siren arc had us listening through tears. This method could have easily replaced the game's voxophones. It would have even fit the narrative of Columbia being a place coming apart at the seams.

I digress. As richly detailed as Columbia is, it never becomes the driving force, the focus. This isn't a bad thing; it's just not that type of story. Infinite places more importance on characters and themes. In fact, Columbia's fate seems more to reflect another character's fate. And here, I think, is where the best lens lies.

6) "BIOSHOCK INFINITE IS ABOUT ELIZABETH."

With this, all of the game comes into singular focus. The pieces I've read about Bioshock Infinite refer to Elizabeth as the best escort/sidekick character in recent gaming history, if not of all time, because of how resourceful she is. She begins as a Rapunzel needing rescue and no sooner than we meet her does she shatter those expectations. Helpless damsel? This one bends space-time, leads instead of follow, scavenges the dead for items, and proves instrumental to the plot as an active secondary protagonist.

But she's only barely a "secondary" protagonist.

With one assumption removed, my entire perspective on Infinite was transformed. It's a basic tenet, one that pervades not only games but any story-driven medium, so fundamental I had to finish this game three times to overcome how ingrained it was. Simply put, you play as Booker DeWitt, ex-Pinkerton agent and private investigator based in New York on a mission to clear a debt. You are the narrator and central POV, but you are not the protagonist of this story.

True, Booker occupies our point of view. He enters with a clear purpose, stepping into the unknown of Columbia through stormy skies alone. He holds the gun, rides the skylines, and opens the doors. Yet after we meet Future Elizabeth, the story unmasks itself as The Battle For Her Soul. All builds towards her character development. Comstock grooms his Lamb; Booker wants her to be free; the Vox tries Liz's resolve; Daisy kills her innocence. Even the linearity of the game factors in because Booker is not the one with the big decision. At best, he's a catalyst.

Booker is also never quite developed in parallel to any other character, only independently. Although the story was in more dire need of comparisons between Booker and his alternate self Comstock, there's one other character with whom he shares some striking similarities. I looked again at that ending scene. Tell me: who is really depicted in this picture?

The bookends of the final sequence: All-Powerful Elizabeth drowns her oldest friend, then Legion Elizabeth drowns her first and last hope(s). These two ship-destroying characters are juxtaposed with purpose. It's a shame that Songbird's role was so reduced by (I'm assuming) cost constraints, relegating his unstoppable-ness to "telling" rather than "showing" via encounters that can't be classically won. We might have caught a glimpse here of how obstinate the two forces were, like The Shield That Always Blocks and The Spear That Pierces All.

Yet the correlation is still canon. All along, Liz wasn't the trusty sidekick to action-man Booker; Booker was the blunt instrument of Liz. The brawn. The muscle. Not a gentleman who opens a door for a lady, but a bodyguard who clears the way for his master. Booker is a wrench, a gun. Booker is just another Songbird.

Think about how Booker's motive changes yet his goal stays the same: get Elizabeth. The Luteces record 123 Heads; Booker doesn't row; Songbird always stops him. He doesn't deviate because he has no big choice to make. It's Liz who saves him from Songbird by surrendering to it, even having asked Booker to kill her if that were to happen. When she chooses to wipe Comstock from existence, Booker declares he'll be the hand to do it. By all accounts, Elizabeth is the story's true protagonist.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Bioshock Infinite is a linear game. A visually stunning game. A violent game. Most of all though, it's a game that held a mirror to the industry and incited so many worthwhile conversations about the state of AAA, the need for combat-less story-driven games, and sure, even the can of worms that utilizing a multiverse narrative unleashes.

On this last one, my biggest complaint really is how Elizabeth becomes so powerful by only losing a pinky. The loss should match the gain. If she had lost her whole hand at the portal's closing (which would surely be too gruesome to show), it'd make her powers seem better earned and create an interesting parallel with Booker's "AD" brand.

I'd like to say that Bioshock Infinite is a game that began/continued/signaled a small revolution. It's too soon to tell for sure. It has its flaws like any work does, but it's no typical game that gives people pause, makes them reflect, makes them discuss the future of the medium. No typical game at all. Because of it, and likely other predecessors and successors, we may be on the eve of something right now, seeing into the radical change of a coming storm.

The delicious question is 'when.'

---

Edited and reposted from my personal blog.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)