Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

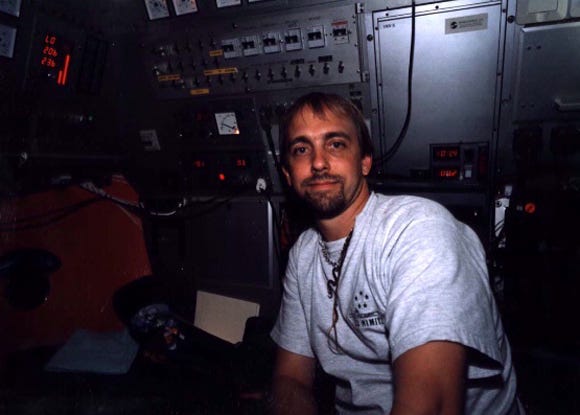

You may think you know Ultima and Tabula Rasa creator Richard Garriott, but do you really understand Lord British? Gamasutra goes off-topic to chat to Garriott about games as art, his influences, and much more.

February 8, 2008

Author: by N. Evan Van Zelfden

Everyone knows about Richard Garriott, how he started programming games for the Apple II, how Ultima became the first honest-to-goodness franchise in the game industry, how Origin "created worlds," including Wing Commander and spin-offs like Ultima Underworld.

Everyone knows how Garriott convinced Electronic Arts to fund Ultima Online, which would be the first great Massively Multiplayer Online game, how he later left EA, and became a vital part of Korean online pioneer NCsoft's plan to capture the American market, and how his second MMO, Tabula Rasa, launched at the end of last year.

Everyone knows about Garriott's larger-than-life pursuits: his dream of going into space, how he went to the South Pole, the wreck of the Titanic, how he boxes regularly and participates in community events, lives in a remarkable castle in Austin, and is building an even grander sequel to Britannia Manor.

That's because most interviews with Richard Garriott ask all the same questions. "Usually they are quite traditional," is how he puts it. The man is no stranger to interviews -- in fact, the same day that Gamasutra conducted its in-depth chat, he was being shadowed by an editor from Focus, Germany's equivalent of Newsweek, who wanted to see a day in the life of the game developing Texan.

"The questions you've asked today are not the usual drift," Garriott told Gamasutra. And below, he explains why game developers aren't artists, but could be, why he only speed-reads games, and how the PC in your pocket just might be the next great platform...

Are you tired of talking about MMOs?

Richard Garriott: No, because I'm actually still excited about the MMO space. As you've probably heard me say before, the MMO genre -- even though it's ten years old, the most anybody's ever made is two, because the retool cycle is so long. I think the industry is still in it's infancy. I'm still quite excited about it. So no, I'm not tired of talking about it yet.

Are games art?

RG: Are games art? They can, and I think, should be. How much "art" there is in a game is up to the developer.

There's a lot of games which I'll describe as just pulp, but absolutely: I think there's lots of great art in games. A lot of my favorite games, actually, are the ones we think of as the most artistic. Games like Myst, or American McGee's Alice, Abe's Oddysee...

So are game developers actually artists, or are they just code monkeys trying to bat about aesthetics?

RG: Well, to make a game now requires such a large staff that you have all walks of life involved in there. I was just listening to NPR radio in the car on the way home from the airport last night, and they had a carpenter who had just gone off strike and was getting back to work on Broadway.

I would not consider that carpenter -- he was probably not what you would call an artist, he was probably literally a carpenter. And the same thing's true in making games.

We have people you might consider the carpenters of the game building -- who would not care, or [even] be too concerned if they were described as artists. On the other hand, I think a lot of the designers and a lot of the artists probably do aspire to be creating things that would be considered great art.

Many people in the industry feel strongly, like you do, that games are art - but does it really matter in the grand scheme of things?

RG: Well, no. If you think about the purpose of most people in this business, I think most of them are in the business as a business. They're here to make money. They're here to find something that becomes popular, and therefore sells well.

However, I think if you look at the measure of what it takes to become popular, I think there's a variety of factors that make games become popular.

I think it takes a combination of things. For example, addictive game mechanics. The kind of "pull the lever on the slot machine and occasionally get a return," which I would not call art, as much as a science.

But another thing that can create popularity in a game is to be attractive -- which could just be nice aesthetics. But another one would be to be compelling. I think what makes this compelling at a more human level is when you can touch people at an emotional or psychological level -- which I would consider art.

Games have a technical barrier as well, something that you don't see with most art. Is that a curse, or a blessing?

RG: It's both. It's definitely a combination. In many ways actually, I personally find it a bit of a curse, only because I happen to be one of the people who try to pursue the art side of it more than a lot of developers. The problem is that, as the technology moves forward so quickly...

I'm a big believer that every time there's a substantial leap in technology -- and I would describe those as things like when CD-ROMs first became available. Or when 3D graphics hardware first became available. Or what happened when the internet first really became available.

What happens is the artistic side of the gameplay pretty much goes away. Instead what happens is people rush to take great advantage of that technological advancement, and gameplay usually becomes very simplified, again. Everything becomes "run around in a maze and kill each other". But it looks so much better than it did before that it sells well.

But then, to compete with that, you have to make a game that's a little deeper and more interesting. A little deeper and a little more interesting. And then, in my mind, it gets interesting as games get deeper, up until the next technological shift, in which case it resets again to the lowest common denominator.

So I go through "cycles of happiness," you might say, with games. I usually enjoy it more when people are adding depth versus [going] back to that simple gameplay again.

John Riccitiello recently told Reuters that the next-gen transition was over.

RG: What EA is concerned about, and I think it's echoed by most game developers, is that the technologies are now so complex that just to put an object up on the screen requires a code-base that's enormous.

So every time there's a new platform that comes out, it takes a year or more, just to develop the software tools to crate the same gameplay experience that you had on the previous machine, but just taking advantage of slightly better graphics or sound or input controllers or whatever the advancements might be.

That's a real concern for our industry. The time and dollars that it takes to bring anything to the table is now going up at a pace that which is growing probably faster than the market size. And so that's a real problem.

You've been able to side-step the console issue, for at least the past ten years.

RG: I have. But what's fun is... even when I was doing work back on the Apple II, there were already the Atari 8-bits, and the Nintendo cartridge machines and things, too. Even back in those days, people were talking about "the death of the PC," and "the rise of the console." And today, people are still talking about the death of the PC and the rise of the console.

But I must say, though, that the line between the two continues to blur, especially now that a lot of consoles are online and now a lot of consoles have pretty sophisticated input devices.

Called keyboards.

RG: Called keyboards, exactly. Or, close enough. To where the opportunity to do PC-like experiences -- which is what I like to do -- but do them on the console, is actually becoming practical.

And so while I'm not sure I personally will be developing on a console, I think you're going to see my company, NCsoft... we've already announced we have a deal for the console [on PlayStation 3], and we're starting to move some products to the console.

Is it the type of thing you're interested in experimenting with, or do you really want to avoid it? What's your feeling towards consoles?

RG: Well, it's complicated. I am not generally a console gamer. Therefore, I think it would be risky for me to become a console developer. Because I think that it's important to develop on the platform, and for the market that you understand and are passionate about.

I think that [at NCSoft there is] some risk of that movement. Except that, again, they're coming so close together, the gap might be close for me. But if you ask me today, "are you going to go make a console game tomorrow?" the answer is still no.

But if you ask me a year from now, you know, I don't know. I can see the gap closing so I can hypothesize that I might someday cross that bridge.

What about mobile games? Do you ever play with cell phone games?

RG: Absolutely. In fact, that's actually the area that, other than PC games, I'm actually most enthusiastic about. The problem is that I'm also a skeptic.

I wish that it would come true, I want it to come true. My favorite Ultima, other than a PC Ultima, was the Runes of Virtue we did for the Game Boy, which was only a shadow of a full-blown Ultima, but was a really good game -- and on a Pocket PC, I [have] it [here] in my bag. I carry a Pocket PC, I've owned pretty much every Pocket PC, looking for the optimal, the ergonomics for me personally, as well as pondering gaming on these devices.

The problem is: the device is still too slow. Especially when switching applications or doing fairly complex things. And the input -- even on simple games, like when I downloaded a version of Frogger, which you would think would work fine on this little display -- but the reaction time of the little four-way controller and your character...the lag is still enough to where you couldn't play the game very well.

So I think the technology still has some work to do before mobile games really become popular.

John Carmack from id Software often says that the cell phones of today have more processing power than the early computers that he programmed.

RG: Oh, that's absolutely true. And more memory.

He loves the platform because it's so simple. And he's also saying that he made all of the mistakes on those very old systems, so now he knows what to do right on the cell phone. Do you think you'd find that?

RG: Oh, yeah. And if the operating system (so to speak) on them were sufficient, if the input on them was sufficient, I would agree.

So you could do a little Bluetooth controller.

RG: [Laughs.] Hypothetically. Unfortunately, still, if you're in the middle of playing a game and the cell phone rings, it often takes seconds to transition from one application to the other. And that's really just insufficient for practical use of these devices. So there's some fundamental architecture shifts that I really think need to take place.

If you did a cell phone game, would you want to do something small and original for it, would you want to do an extension of Tabula Rasa, would you want to use an old IP that you have sitting around?

RG: I would do something original, but probably familiar. Here's what I mean. When I describe the Runes of Virtue on the Game Boy as my favorite non-PC game that we did -- when we tried to translate Ultima onto consoles, when we tried to create the Atari 1600 version of Ultima V or whatever, those games were terrible.

And the reason why it didn't work very well was because the PC is a very big platform, we shoehorned it into the 8 or 16-bit console. The graphics looked worse, the game was kind of stripped: it became a clearly inferior shadow of the original. And so I don't think it was really very fun.

When we went to make a Game Boy version, you really couldn't shoehorn one in. It was so much smaller that really all you could go is, "Well, what is the essence of an Ultima?" and "Let's go make something that's Ultima-like, but is really designed for this platform." And that game was actually a really good game. And it felt like an Ultima, it was clearly an Ultima in my mind. But it was designed from --

You built it from the platform up, instead of trying to reduce it.

RG: ...the platform up. And so that why I probably wouldn't do any translation onto [a smaller platform]. Even if we used an IP like Tabula Rasa, that would only give people some familiar grounding of visual style.

It would be the same logo.

RG: Yeah, exactly. But otherwise it would be completely different, ground-up game.

GS: I wanted to ask you about areas of familiarity. What do you keep up with, and what's off your radar?

RG: As a gamer, I'm actually surprisingly ignorant of what's going on... many of the popular products I've of course heard of, a few of them maybe even purchased the box, like I have a BioShock box on my desk, that I've never installed for about three months now.

But I bought it because I saw other people playing it and it looked like something I'd be interested in so I actually went out and bought one. I just haven't even found the time to put it in.

There's occasionally things, like the Portal game in The Orange Box is one that I've observed and think that it would be interesting -- I've watched it be played -- but I've never played it. And so it's really only one game every few years that I actually manage to get to play.

Does that concern you? And this is the story for developers across the board -- they never actually have time to play games, they only have time to make them?

RG: Not really, because I think that, at least I have found, that by observing other people play, and then these little windows, brief windows of time that you get to play the games, you...

When I do play games -- with the exception of the ones I already mentioned like Myst, and Abe's Oddysee, and American McGee's Alice, which I played because I really enjoyed them, and I played them to completion -- most of the time when I play a game, I play it for like two hours.

And I play it to really get the gist of "what is their big advancement," UI theorem, what's their render pipeline operating like, what is their mission cycle organized like. And so I'm studying it. As soon as I think I've got the gist of it, I'm done, I move on.

But isn't this like the Great American Novelist who reads thirty pages of Nabokov, then thirty pages of Tolstoy, then thirty pages of Faulkner --

RG: Oh, totally. But here's what's interesting is, I'm very much what you might describe as a non-reader. I've read Lord of the Rings multiple times. I've read the Chronicles of Narnia multiple times. That's about it. The other, even fantasy or sci-fi works that I've ever read in my whole life, I'm sure numbers less than five books total. Even through school.

You might think of that as a big deficiency, and it probably is, when you're trying to do something artistic or literary, I'm sure that's a deficiency. But what's interesting is, as I grew up as a game designer, I instead have become a devout researcher.

And so I have a whole research library now. On every subject I try to tackle in games, I go buy -- not just a few books -- I buy a shelf of books on the subject, whether that's philosophy, symbolic languages, architecture of various eras and countries. While I don't read it cover-to-cover, I do study it and find passages and paragraphs or chapters that are exactly what I need to digest in order to become quasi-expert on a subject.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like