Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Interacting with the World of Elsinore

Elsinore is a game about manipulating events in order to try to prevent the tragedy of Hamlet, but the actual methods of manipulation have changed over the course of the project. This post explores those changes, why they occurred, and their benefits.

This is one of the Dev Logs for the indie game "Elsinore." If you would like to see the other logs (there is only one right now!) check them out here. Or, you know, follow us on twitter. :)

So! Brief overview. In Elsinore you play as Ophelia, who finds herself trapped in a time loop as the tragedy of Hamlet play out over and over around her (think Groundhog Day plus The Walking Dead). The characters of Hamlet move around on their own schedules, scheming and plotting and gossiping as the player explores her surroundings, choosing which characters and schemes they are going to follow and try to influence in order to prevent things from spiraling into a bloody end.

This basic idea has remained essentially unchanged since the beginning of the project, but the actual way it was implemented has shifted dramatically. In this post I'm going to explore one of these design evolutions, and why it occurred.

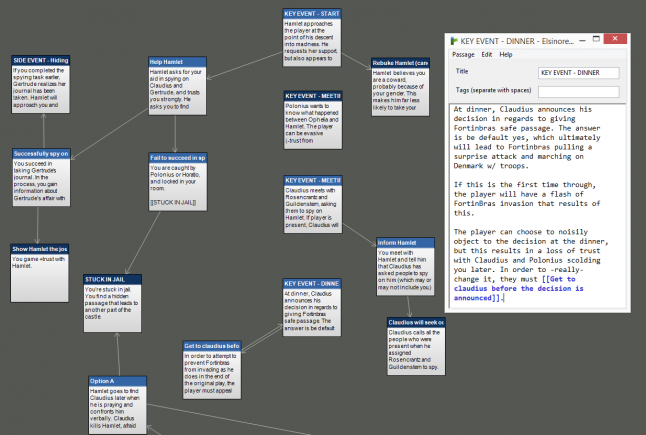

Originally, we were shooting for "scenes" with branching dialogue, along the lines of The Walking Dead or Mass Effect. If the player walked into a room while an event was taking place, a scene would trigger, and Ophelia's dialogue choices and actions would affect which later scenes occurred and what their outcomes would be. In this format, Elsinore was composed of little branching adventure game vignettes, found by being in the right place at the right time. We would map out these progressions in Twine, one of our early attempts at which can be seen above.

This would have been in line with proven adventure games, but this idea quickly became muddied when time loops were involved. We wanted to have the player's tools expand each time they restart from day one; in loop four, Ophelia and the player will know things that they did not know in the first loop, and their options should expand accordingly. Branching dialogue trees don't really lend themselves this idea naturally - in such a model, we would have to have a thousand different flags throughout the game to make new dialogue options appear in the appropriate places.

Furthermore, no matter how much we broadcasted where these new options would be, accounting for all the different ways a player might want to use their knowledge proved to be a herculean task. Theoretically Ophelia could apply knowledge she learned anywhere -- If she finds out how her father is going to die, for example, couldn't she reasonably decide that was relevant to bring up at any time, to any character? Extend this to all the different things players can learn, and you have a massive content explosion.

Clearly, we needed to consider some other options.

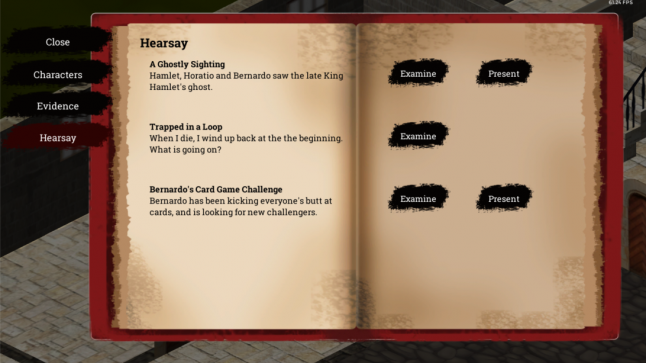

The system that we wound up using is one where the player collects pieces of information, or "hearsay," by witnessing key events and learning new things. This hearsay then persist across loops, so once she obtains it, Ophelia is then free to present hearsay to characters at any point in time. These characters will react to the things you tell them, potentially giving you new information or influencing the way they interact with other characters. This solved the problem of us needing to define when the player can use their new knowledge, as the player can present their information at any point -- Ophelia can warn individuals about her father's death whenever she pleases.

This new system also drastically reduced the content explosion involved in each branch. The player can still stumble upon the scenes as they are occurring, but unlike the original model, with a few exceptions the scenes are unalterable once they begin to play out. It's what the player does beforehand, the knowledge she presents to others in the gaps between scenes, that can cause the world to spin in different directions.

Even though Ophelia can tell anyone that her father has died, her telling people occurs outside of the context of scenes -- dramatically reducing the number of times the direction of the scene would need to change. With fewer possible outcomes for each scene, we are able to have more scenes and more branches -- and since the changes are second-hand, we can more smoothly control these possibilities.

One final thing: In addition to being a better fit mechanically, this new system wound up working better for us thematically. In the original play, Ophelia was not an active participant in the events -- in fact, she was marginalized or sheltered by most of the important figures in the castle. An in-depth discussion of our exploration of this dynamic is a discussion for another time, but our initial gameplay directly clashed with Ophelia's character and the social constraints of her world. She exists in a time and place where her opinions are ignored and her voice is not heard. In order to create change, she has to be smart, sneaky, and subversive -- and in turn, this new system helped form a more accurate Ophelia who is, overall, more nuanced in her actions.

So in the end, we were able to find a method of interaction with the world of Elsinore that made the entire experience much more cohesive, while keeping a lot of the elements that we wanted before.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author

You May Also Like