Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How Call of Juarez Gunslinger's storytelling went from idea to reality.

The story of a video game story, from two very different angles : writer and producer.

This is a story-driven blog about the development of the narration of Call of Juarez : Gunslinger; co-written by Xavier Penin and Haris Orkin.

We thought it’d be interesting to share the experience of working on this fourth installment of the series, from two very different perspectives, so that’s how this blog is structured.

Please forgive us for the length of the following text, we both love to write.

X.P.

When we started drafting the game with Techland, we had a few guidelines we really wanted to stick to, because we were on a mission to save the Call of Juarez brand, literally.

We knew coming back to the old west was a must, not only because of the reactions to The Cartel, but also because the fans of the series told us, quite clearly.

We knew this game would have a limited scope, and be digital-only. We needed to focus our efforts and money on things that would be useful. At first, the story did not appear as such on the Ubisoft side.

Actually, if we quickly agreed on a shortlist of must-haves, like a clearly iconic old west setting, fast-paced and arcade-ish shooting gameplay, the necessity to have a strong visual identity, a secondary mode that would provide replayability, and a way to develop the main character through some kind of skill system, we believed the main game mode should be divided in small chapters that could be played almost in any order so we could cut one or two if time or budget demanded it.

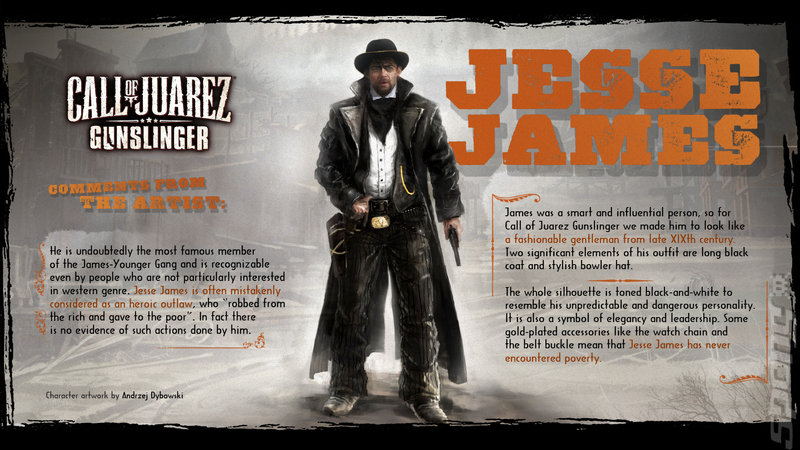

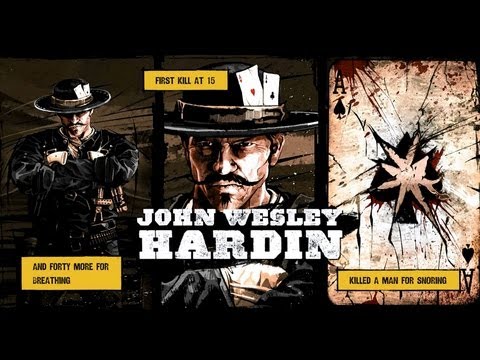

What we proposed was that our hero would encounter legendary characters of the Wild West, and that each of them would be central to one “chapter”, which could be made of one or two missions.

It would be the occasion to unravel some “hidden truth” about these characters, like “Jesse James was not really killed by Robert Ford…it was ME who killed him and had Ford to take the fall!”. That seemed strong enough to flesh-out some story for each chapter.

We wanted to avoid any kind of global plot that would require us to link all these chapters logically. Actually, it would also save us from having to justify how our hero could have met all these legends in his one and only life.

The 2D / comic book-style animatics were part of this relatively cost-conscious strategy. We wanted to spend money on short, efficient animatics, to open and close each chapter.

But we should have known better, having worked with Techland before, that they would want to make a story-driven game.

H.O.

I was very pleased when I heard we would be returning to the Wild West for Call of Juarez: Gunslinger. I’m a huge fan of Western novels, films, and history and I couldn’t wait to step back into the past.

I mainly worked with the lead producer on the project, Krzysztof or Chris as he suggested I call him. (Probably so I wouldn’t mispronounce and mangle his name.) He and Rafal, the other writer on the project, came to me with a few of the levels already built and a basic idea of what they wanted the game to be about. They didn’t have characters or a story yet. In fact, the publisher, Ubisoft, wasn’t entirely sure we needed a conventional story as the title was slated to be an arcade game. But they also said they wanted the game to feature some of the most iconic Western legends and characters from the past and I thought that was a great idea.

Together we crafted a story based on that premise. The player would be someone who brushed against all those famous characters. Rafal had already been thinking about this and I joined the effort. I felt like it was important to have an overarching story to tie it all together. I was worried that without it there wouldn’t be enough of a narrative drive to help pull the player through the game. Also, as it was an arcade title, there wasn’t a budget to pay for expensive CGI cutscenes. The cutscenes would be 2-D comic book style illustrations. Sometimes, however, limitations can help our creativity and in this case that was absolutely true.

X.P.

It’s important to notice that we’ve given Techland quite some freedom for this project, compared to many other ones, including the previous titles we developed together.

That new approach did not go unnoticed, and quickly, Techland came up with new ideas of their own, that they would fight for until the end of the project, especially the unique narration style of Gunslinger.

Soon after this agreement on a new partnership, Techland delivered a game concept document that was supposed to ensure that we shared the overall vision of the game. The first notion of spoken narration appeared, raising questions on our part.

Notice that at this stage, we did not have any writer in the list of key people involved in the project on Techland’s side. We never met Rafal W. Orkan, Techland’s writer who was at the origin of the story, and Krzysztof would continue to be our main contact regarding story, until the end of the project.

Nevertheless, during a visit to the studio, Krzysztof Nosek, the producer of the game presented us with this idea. We felt like the ownership we’ve given to the studio was already paying off:it was a surprising, interesting and daring idea.

It was still blurry at the time: an old drunk telling stories in a saloon to a band of patrons. He would tell the truth, or not, be challenged by his audience about the veracity of certain details, would change his story on the fly, and so would the gameplay, the level design, the balancing of the mission.

Krzysztof had played Bastion and was obviously influenced by it.

We were enthusiastic, but also frightened by the ambition of this feature. We feared it could bring doom to the game as much as success. It felt hard enough to get a compelling story with the means we had in mind, and now we could foresee the added work and time needed to match level design with dialog, the unavoidable rewrites and the bugs that such a feature would generate.

It also had the power to trigger our imagination. We knew it could be powerful, but wondered if our Techland partners really realized the challenge they were up to.

Anyway, the deal was to let them do the game they wanted, and we knew it was the onlyway to get the best out of them, so we supported the idea and just made sure to give constantgive feedback on the execution, even if it had to be hard, at times.

Shortly thereafter, we received story documents; including one from Haris, entitled “The Shootist”…that guy had a sense of humor, for sure. To me, he was one of the Bound in Blood writers and that was good enough, since I had reviewed the script back in 2008, even if I had not met the man.

This first piece of dialog gave the tone of what Gunslinger would be in the end. Surprisingly, the vengeance backstory that we feared would be grittier and darker than ever (another of Techland’s signature trends), was full of humor, which gave a fresh taste to the Call of Juarez series and its uniqueness to this new game.

H.O.

Right from the start, the team at Techland knew they wanted to use a narrator throughout the game. Something in the spirit of Bastion. Call of Juarez: Bound in Blood had two main characters and the continuing dialogue between themnot only deepened the characters, but helped to propel the story forward. Instead of happening in real time, however, the narration in Gunslinger would be told as a flashback and that offered us all kinds of creative license. We decided our narrator would be unreliable and that the world would change as the story changed. I thought that perfectly mimicked how the history of the West was written in the first place.

I sent them images of dime novels from the Autry Museum in Los Angeles. The Autry Museum is probably the world’s greatest repository of Wild West memorabilia, history, and research. The cutscenes would be done in a graphic novel style, much like the lurid illustrations in the dime novels of the time. In fact, the lead art director, Pawel Selinger (my co-author on the other COJ games) wanted to use a subtle cell-shading in the game’s visuals. That also mimicked the idea of Gunslinger being a dime novel brought to life.

I also thought that the use of this unreliable narrator would help us with a narrative problem always present in shooters. Ludonarrative dissonance, a term first coined by Clint Hocking, is when the game’s mechanics directly clash with the narrative and story. Most playable characters in shooters are brutal mass murderers, mowing down hundreds if not thousands. Yet, we still want the player to believe the person they are piloting has a conscience and is not a complete homicidal maniac. In Gunslinger the story-teller is exaggerating his exploits to improve the story and make himself into more of a hero than he might have been. Since the player is playing his story, it makes sense (and makes fun of the fact) that he/she can defeat hundreds of enemies single-handedly. It also explains why the enemies are such awful shots. Silas, at one point, even mentions the fact that his opponents can’t shoot worth a damn, yet have a seemingly endless supply of ammo.

X.P.

We quickly got the first iterations containing WIP voice over and even the first of what we would eventually call “narrative twists”. It was the first mission of the game, which was chosen to provide a showcase of the game: it packed some attacking gameplay, then a defensive situation, a duel, not one but two legends of the west (Billy the Kid and Pat Garret) and a narrative twist.

This was the beginning of my worries. At first, I did not like this first twist, I thought it was anticlimatic, and the whole thing finished with one of the tricks I hate most in shooters, i.e. being knocked down by a script.

You face Pat Garrett in a duel. Well, many people may not know the story, but for me it’s kind of common knowledge that Pat Garrett killed Billy the Kid(or at least is believed to have done it) because Garrett betrayed him (I was 15 when Young Guns was released). So you would know that something was off, but that wasn’t the problem.

You beat this legend in a duel, and then, oh, no, you did not! This works if you see yourself as the audience of Silas Greaves, but if you see yourself as the gunslinger himself, it’s like taking away your performance, your kill! There was a cut to black and you would “respawn” where the duel had happened, walk to the barn and get another cut to black: oh, you’ve been knocked out!

I hate to be knocked out because I opened a door and got surprised by some guyin a game that allows me to shoot thousands of foes and get shot at a thousand times without dying. Did I just hear “ludonarrative dissonance”?

Right nowit may look like I hate this, so allow me to continue this topic a bit further.

We put some pressure on Krzysztof about this and many other of these moments in the game. This one was made much better by the following iterations, including a video rewind effect, the voice over, the addition of an achievement that underlines the fact that youactually…well…achieved something. I admit it works in its final version, even if it’s not my preferred moment.

During the following months, we had difficulties getting precise information on the other narrative twists in the game. The story was being written but it wasn’t really possible for us to foresee how it would translate in the game. We had to trust a lot.

One of the other big topics and reason for friction between Ubisoft and Techland was the amount and exact placement of the voice overs. We advocated less talk, and no talk during shootings. We probably failed to explain that we did not dislike the whole system but really believed that in this specific case, “less was more”.

So we pushed a lot to reduce the volume of text and it was a painful process. We never reached a perfect agreement, but I still believe this push helped, in fine, to get a better quality.

Personally, I also criticized the structure of the story, and more precisely the timing of information delivery to the player. We felt that on Techland’s side, there was a fear of revealingtoo much about the game’s ending, including the Easter egg about Dwight.

Reminding Techland that all our data tells us that very few players (even on a hardcore segment) actually finish games did not help. I admit it’s a fact that hurts me as it would anyone who loves story-driven games, but it’s still a fact. “Lots of player will NEVER see the end of your game, anyway”, I said. Probably not my smartest comment during this project.

Also, among all the players who are going to complete the game, how many will have followed the story closely enough to benefit fully from the craft you’ve put in it?” I’ve heard so many times players stating that they didn’t even care about story…

So my advice was: don’t focus too much on making a perfect ending and protecting your users from spoilers. Instead, focus on the part of the game all the player will experience: the start. If you’re too murky and if your hero’s motivations are unclear for too long, you may simply lose your audience and they won’t care about the story. Let’s give them anincentive to get to the end.

I always like to quote Blake Snyder and his golden rules of storytelling (even though his theories apply better to Hollywood movies than to games), but his adviceon story is that you should start fast and get your audience on board quickly. The motivations of the main character must be strong and clear, right from the beginning.

That’s why I wanted to quickly give the player the information that Silas Greaves was not here without a reason. That hidden agenda is revealed quite late in the final game, but there are numerous hints that can tell the player that something’s going on. What if they guess the ending? Well, they’ll want to check if they’re right anyway, I suppose.

When the saloon’s patrons first raise the possibility that Greaves is lying intentionally, the game’s audience might start to wonder why, and to me, that’s the beginning of the real story, before that it’s just exposition.

Finally, we learned that Haris was working on iterations of the narration and in the end,Krzysztof told us that the whole narration needed a polish sprint, with possible changes everywhere in the game.

From my point of view, it was too costly for a game that should not rely on its story to sell or get good reviews. But again, we accepted Techland’s decision to invest on that. And it was the right decision.

H.O.

The implementation of the narration and how the narrative tricks would work took a lot of iteration. We had to record a lot of placeholder dialogue and lay it in the game in order to find out how much was too much. The pacing and timing would have to be perfect and that’s pretty tough when you’re talking about an interactive medium. There would be a narrative through-line for each level, but the majority of the dialogue needed to be modular and triggered in different places on the map depending on which route the player decided to take. We spent a lot of time on that first level trying to get it right. It was tricky since I was in L.A., but I played through every build and gave them my notes and the team at Techland was very responsive. Krzysztof also did a great job of shielding me from Ubisoft’s misgivings. He was the guiding force on this project and held it all together, balancing our limited budget with our unlimited ambition.

I pushed for more dialogue, rather than less, knowing it’s easier and more cost effective to cut lines than it is to add them later. And I was glad to cut anything if it helped improve the pacing.

I was actually of the opinion that we should set up the whole revenge story right from the start. I didn’t want to take too long to get the story started and apparently Xavier felt the same way, though I didn’t know it at the time. The team at Techland, however, didn’t want to give away too much too soon. We settled on a compromise which I think ended up working well.

Because a third of the levels were already constructed (or partly constructed), we needed to build a story that would match the existing levels. It also needed to make sense in terms of when and how Silas would meet those characters from history. We wanted to play with history, but keep the timelines and characters as close to reality as possible. Though reality, when it comes to history, is a pretty malleable concept and this was especially true of the Wild West. Legends were created to entertain the masses. First in dime novels and later by Hollywood. So what is true and what isn’t became a big theme in the game and there were favorite movies of mine that played with those themes and offered inspiration.

The first film I thought of was Little Big Man, a movie directed by Arthur Penn, starring Dustin Hoffman. It followed the life of a fictional character who brushed against many of the Wild West’s greatest legends. Another movie that came to mind was John Ford’s iconic Western, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.” One of the famous quotes from that movie informed the entire project for me. “When the Legend becomes fact, print the legend.” That’s pretty much the central theme of Call of Juarez: Gunslinger. The collision between truth and myth.

The team at Techland knew they also wanted collectibles that told the real history of the West. I coined the term Nuggets of Truth and we collaborated on writing those as we worked on the game. It became quite ambitious; a little mini-history book inside an arcade game. Being we’re all Western history buffs, we really enjoyed introducing the Wild West to generation of players who may not know much about it.

X.P.

The game was reaching its final stage. Besides the arcade mode which was also better than we had expected, we were finally eager to tell our management that Gunslinger’s narration had become a unique selling point. Maybe not perfect, still with a risk of disappointingcertain players, but yet something new and never seen before.

We had come to love some specific moments and I personally love the ending, from the ghost town to the final choice. If I initially doubted the power of the whole overarching plot, in the end, I can’t deny that the story of this old man who has spent a lifetime killing and looking for revenge, now finding himself crying for all he’s sacrificed and wondering if he should complete his journey to the dark side or finally choose redemption,is much more than I expected when we first starting working on this game.

H.O.

As we figured out the story, we had to keep rearranging the order of the levels. At the same time, Techland had a big list of narrative tricks they wanted to try. I contributed to that list and we had to decide which levels to put them in and how best to implement them. Krzysztof told me which of my ideas were possible and which weren’t technically feasible. Amazingly, the team was able to make quite a few of them work.

That ghost town level was a bitch to put together and you can blame me for the concept. I’m guessing the level designers were probably cursing me out as they were struggling to make it work, but in the end they succeeded brilliantly. I also suggested we create a choice for the player at the end. The story was about revenge and the price one paid for seeking it. I thought the final decision should be up to the player. I also thought it would be great to have one more twist at the end and that’s how Dwight came to be. While doing research on Abilene, Kansas I discovered that its most famous citizen was an avid poker player and loved tales of the Wild West. He would have actually been the perfect age to be in that saloon and listen to those stories.

Besides writing the script, I also cast and directed the VO talent for Gunslinger. Since Silas Greaves narrated the entire game start to finish, finding the right actor was of paramount importance. Anyone who came off the slightest bit annoying would sink the entire enterprise. A lot of really good actors auditioned for the part, but I had worked with John Cygan before in Bound in Blood and I knew he could pull it off. He’s a very successful voice actor and has been in many games and animated movies. Not only was he great at following direction, he would also bring his own ideas to the character and story. I needed someone who could not only play the comedy, but also the drama. Luckily, everyone agreed with me. Other actors I’m sure would have done a fine job, but John really made Silas Greaves his own.

The final supporting cast were all equally talented and experienced and brought a lot to the story. If any one character is weak, it brings everything down. A story is only as strong as its weakest link.

X.P.

The game was finally out and we started watching metacritic like any other game developer, I suppose. The first day was a rollercoaster, with a first very tough 50 to start with, on pc, followed by very few other ratings, all between 70 and 80.

Strangely enough, the best ratings came a week later, with two precious 91 and 90.

The first bad rating had not killed us, actually, the ratings rose for two or three weeks, which felt somewhat surprising, but pleasing.

But to come back to our topic: the story was well received. Nobody seemed to hate it, and most reviewers really liked it, as they did the main character.

We finally had the answer to our anxieties: it worked. It was a good idea, and well executed.

Also, as Krzysztof had hoped, not only was it a nice addition to the arcade shooter that was Gunslinger, but it had become its signature, the feature that made it unique.

H.O.

We were all very gratified to see the reviews. People really seemed to love the game and the character of Silas Greaves and the way we told the story. The arcade mode was a brilliant addition. My son is totally hooked on it. (He puts his old man’s scores to shame.) What really pleases me are the player reviews. It’s unusual when the cumulative user scores are higher than the scores from the professional critics. I think that’s a very good sign.

X.P.

To conclude, even if it’s easier to say it now than before, it appears that Techland was right to pursue their ambition of delivering an original and strong narrative experience within this piece of digital entertainment.

May it be a lesson we all can use in our future video game endeavors.

H.O.

You never can tell how the press and the public will react to a new title and I give the folks at Ubisoft a lot of credit for taking the chances they did with Gunslinger.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)