Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The "10 minute rule" governs the creation of films, but is there a similar rule that could apply to game narrative? Game writer and academic Leanne Taylor discusses the possibilities, and examines narratively successful games for clues.

November 18, 2010

Author: by Leanne C. Taylor

[The "10 minute rule" governs the creation of films, but is there a similar rule that could apply to game narrative? Game writer and academic Leanne Taylor discusses the possibilities, and examines narratively successful games for clues.]

Games are like movies -- or so some would have us believe. With their ever-increasing budgets and graphical realism, they're certainly heading down that path.

In movies, there's something that's colloquially known as the "10 minute rule". The idea is that, after 10 minutes, the viewer will generally have a good idea of whether they'll enjoy the rest of the movie or not.

In games, which are exponential in terms of cost and time for the audience when compared to movies, where does the 10 minute rule lie?

The reason it's called the 10 minute rule is because that's when the hero usually receives their first inkling of the events that are about to unfold: 10 minutes in.

In The Princess Bride, the 10-minute mark falls conveniently on the point where Princess Buttercup is about to be eaten by a Shrieking Eel. If done correctly, this moment will convince the audience to keep watching, in order to find out what happens next.

In a similar way, games need a hook to convince the player to actually start playing. This can come in the trailers, before the game is released. In earlier days, when advertising for video games was all but unknown, it had to come from within the game itself.

Simple and to the point.

Enough said.

Spinning a tale to hook players was where cinematics came in -- they told the player the story, linked the gameplay to something the player could relate to, understand, or wonder about. Far apart from the gameplay, they gave the player a reason to start playing. They acted as the first intellectual or emotional half of the 10 minute rule, with the gameplay acting as the second, tactile half.

This meant that both facets had to combine to create a certain level of interest. Most gamers can agree that if, after playing through the opening cinematic and tutorial, you still aren't hooked, you've got a problem. And, more importantly, as games are becoming more expensive to both produce and procure, the publisher has a problem, too.

Australian price for the Fable III Limited Edition

So it's important to convince the player that they have spent their money wisely. And because games are so much more expensive for the player in terms of time and money than movies are, it has to do so quickly.

The best and most memorable games that I recall from the past 20 years have managed to do this: to hook the player with their opening cinematics. But what made them so compelling? Why did they succeed where so many others have failed?

My theory is this: for original IP, your hook must be some form of a history or a mystery, probably combined. For second forays into a world, you can start to rely on story.

It's easy to discover what kind of hook a certain game has by asking which one of these three things the player will be wondering about by the end of the intro cinematic:

What has happened? (History)

What's happening now? (Mystery)

What's going to happen? (Story)

To illustrate my point, let's look at games from the three Big Bs -- Blizzard, Black Isle/BioWare and Bethesda.

Mystery is the largest category -- for first-run IPs, this seems to be the preferred method of getting and keeping players. In this category, we have games such as Warcraft (2:10), StarCraft (2:19), Diablo (1:47), Baldur's Gate (1:53), Planescape: Torment (1:43), Morrowind (0:58) and, oddly enough, Warcraft III (2:16).

Despite our lone contender at the end, you'll notice many of these games are the first instalment in a series. Sequels generally being a sign of success, we can assume these games did well.

Warcraft

The reason Warcraft III fits into the Mystery category is simple: since there were six years between the last released Warcraft title and when Warcraft III came out, Blizzard figured they would be attempting to sell their product to a new and broader range of gamers, and treated the IP as original. They developed a mystery in line with their lore, and met the Mystery and Story categories in a single two-minute cinematic. The result is something short, compelling, and lucrative.

And disturbing.

History, by comparison, is the smallest category. These games usually have also either a Mystery or a Story to back them up, as history by itself is not especially conducive to gameplay. In this category, we have games such as Warcraft II (1:51) and Diablo II (7:05).

They tell of the events that came before, and are most effective when applied to the player's previous actions. In Warcraft II, you're continuing your battle. In Diablo II, you're discovering the path of the Dark Wanderer -- your own character from the first game. History is more compelling with a personal context for the player.

This again? But I thought... Awww, crap.

This leaves us with Story. In this category we have games such as Warcraft III: Frozen Throne (3:15), StarCraft: Brood War (3:46), Baldur's Gate II (2:52), Oblivion (1:53) and StarCraft II (3:44). The question in these introductions is not What has happened? or What's happening now?, as these things are usually explained. Prior knowledge is used to propel the player into discovery, to lend the unmistakable allure of history in the making.

This guy's face haunted my dreams.

This, I would argue, is the most difficult way of creating a hook, simply because it relies on previous world building and play experiences to generate interest. Important details can be omitted, since the player is familiar with the story at hand, which can also create a Mystery for new players, such as Alexi's obscure response, "Yes, I am ready to go all the way, my good general." If you've played StarCraft, you have some inkling of what they're talking about. And, if not, boy, are you in for a surprise.

In comparison, Tychus looks like he'd kill you in your sleep.

These Story-based games often throw in a motive, such as revenge (Baldur's Gate II) or a Mystery (Oblivion) to give the story more shape, but their underlying message is: Come and create the future. It allows the player to see what effect their actions have or haven't had on the past, and gives them another shot at fixing the world or, in some cases, ruining it forever. While this may be the most difficult category, it's also the most empowering. You want the player to have hope, after all.

But how can you apply this to your own games? Should you?

Arguably, this is simply shorthand, much as genre names are. In the same way that we would describe Team Fortress 2 as an FPS, or Fable II as an RPG, these three categories are a way of asking: What does the player want? What draws the player in?

Is it discovering the past, understanding the present, or shaping the future? What experience do you want your player to have? And, most importantly, how can you make it more personal?

Never forget that we, when playing games, are somewhat selfish creatures. We want the game world to be about us, and we want it to grab us within those first vital minutes and convince us that this game, not that one, is what we need right now. This is where games need to develop their own 10 minute rule, though the "10" is negotiable.

Depending on the length of the game, the introductory hook could come anywhere from one minute to three hours in. But never forget, you do need to hook your player. How quickly you do so is reliant on the gameplay.

The pace of a Story is faster than that of a History, while a Mystery is faster still. Do you want your player to be thrown into your world with a bang, or are they going to spend most of their time exploring? What is the pace of an intended playthrough?

That's a good start.

So here, then, are a few questions to get you started on thinking about where the story should start for your player. The old adage from film -- to get in as close to the action as possible and jump out as soon as it's over -- definitely still has a hand in choosing where to begin, but the how is something you need to know even before that.

What genre is your game?

Who is your ideal player? (Bartle's player types may be of use here.)

What mechanics and plot elements would they enjoy?

What is the main gameplay mechanic?

How much of that gameplay mechanic does the player get to experience within the first "10 minutes"? (Hint: if it's not much, you may want to reconsider than 60 minute opening cutscene.)

How long does it take to play through the critical path of your game?

What are some of the optional mechanics the player can discover (e.g. earning achievements in Team Fortress 2, buying up real estate in Fable II)?

How vital is it that the player knows or understands the backstory?

Who are the characters that need to be introduced immediately?

What can be revealed more sparingly later on?

Are you creating a new IP, or working within an existing one?

How can you save the player time?

That last question is one I would urge every developer to consider. It's far better to leave your audience wishing the story segments were longer than to overload them with information they don't care about or understand.

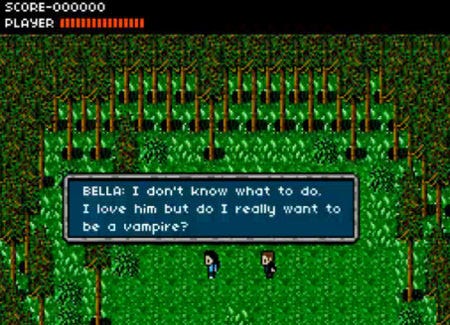

Like, well, any of the Twilight series.

So what does this mean for you, in the long run? Stick to the good old storytelling rules -- the best stories combine inevitability with irony, show don't tell, sometimes the best answer is silence -- but think about how you're delivering that narrative, too. Does it mesh with the player's in-game experience? Does a slow story building to a dramatic finale really suit your hardcore FPS?

In some cases -- Halo: Reach, for example -- the answer is yes. But to be able to judge whether or not your story suits, you need to know who you're making the game for. You need to know what they like, what they love, and what they hate. You need to do research. Once you've done your research, you will know what the first 10 minutes of your game should be. You will have your hook.

Know that, and you will know your audience.

Know your audience, and they will love you for it.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like